Olympic weightlifting has gained immense popularity over the last five years in the US. Much of this increase in participation is due to the enhanced media exposure through social media. What was once an obscure strength sport has become a staple in most strength enthusiasts' news feed. There are several factors that may have lead to this "rebirth' of sorts.

Social Media

I will be honest, back when I started training with weights in 1986, I had rarely seen anyone performing a competition snatch or clean & jerk. The still pictures you may have seen in old books or magazines did not do the sport any justice. Fast forward to when I started competing in 1997 and started coaching in 1998, it was still rare to see any competitions unless you were training at a national level. Local competitions were almost non-existent and the only exposure to seeing a clean performed was in a high school or college weight room.

Well, that all changed with Social media and my news-feeds across mediums were infested with every weekly attempt at a PR in every gym across the country. Olympic lifters and raw powerlifters are now empowered to display every attempt at improvement while broadcasting their inner-self talk through witty banter. My cynicism is sarcastic and I really believe it is a good thing and the exposure has helped the sport from a grassroots level.

CrossFit

When I got my USA Weightlifting Sports Performance Coach Certification at the University of Xavier in 2004, the attendees were almost all college and high school strength & conditioning or sport coaches. Fast forward 5-10 years where we hosted that same (basically) USAW Level 1 Certification and the population had drastically changed to CrossFit Coaches and coaches in the private sector. The CrossFit community uses a heavy dose of the traditional Olympic lifts for their classes and competitions. As patrons of these affiliates gain proficiency and confidence, the need to perform and coach these lifts at a higher level adds more demand to the education equation. Again, this movement is a good thing for all strength sports as there is more carryover between Olympic Lifting, powerlifting, strongman, crossfit, and physique/ fitness in my opinion. Maybe its just these transitions are just more documented now.

The Debate

There are certain arguments in the sports performance field that seem will never be resolved, and frankly, they can't be. One of those arguments that comes up involves the Olympic lifts to enhance athletic performance. The question is often made entirely too black-and-white and avoids the key component of context. Just understanding that every coach and every situation will technically change what is considered "right or wrong" is a step in the right direction.

Knowing What Question to Ask

Before all else, coaches need to figure out exactly what is being asked in terms of the role of Olympic Lifting in sports performance. In seems no matter how the debate is presented in terms of pros and cons the answer coaches may not give but what they are really saying is:

"I like/ don't like Olympic lifting because...."

For the sake of this article, it is important to understand what I am trying communicate based on a specific set of variables. So a more appropriate question might be:

"Is Olympic Weightlifting the most effective method of enhancing athletic performance for field and court sports?"

Now, every strength coach that I know personally would probably say the same thing. "It depends." And that statement alone may be the two words coaches need to have in their vocabulary in order to become a better coach.

So, yes, it depends.

Therefore, we have to determine what are the variables that it depends on. To name a few basic factors would rely on a standard needs analysis and honest self reflection.

The Coaching

Anytime you are programming Olympic lifts, always ask these questions.

- Do I have the knowledge base to teach the bio-mechanical positions and the movements?

- Do I have the experience with identifying and addressing technique discrepancies while instituting corrective strategies?

- Do I have enough qualified coaches for the number of athletes I have at one time in my facility?

- Do I have enough time during the training session, training week, and training cycle with my athletes to ensure technical proficiency of the lifts?

- Do I have enough space and enough stations to safely accommodate novice athletes performing explosive movements (some of them overhead)?

- Do I have the proper equipment (the correct bars, bumpers, platforms, or appropriate flooring) for my athletes to execute these movements?

- Are my athletes' chronological, biological, and training ages all conducive of productive training sessions using Olympic weightlifting movements?

The Climate

One of the most simple ways to convince yourself to undergo the arduous process of teaching and coaching the Olympic lifts is gauging the athletes and the sport coach. This may be an over-simplification but just ask:

- Do the athletes want to do and are enthusiastic about the lifts?

- Do the sport coaches even care?

I realize it is the strength coaches decision to implement these movements into the program, but when there is less resistance, it can make this process much easier.

In my 15 year career, I have had coaches communicate that they want their athletes performing cleans. This has been usually been football coaches, throws coaches, and of course Bobby Ross when I was at West Point. They may not know why, but they see value in the movements. I have ever had a sport coach tell me they don't want their athletes performing those lifts. Maybe they just don't understand them enough to make a judgement or they just thought they looked "neat" or "cool" when they observed their team's training session.

The Cues

This goes along with coaching, but cues are essential for any strength coach. Basing those cues off of your situation and clientele is imperative. One key aspect that some coaches look past is the simple fact these cues will differ depending upon who and where you are coaching.

For example, most Olympic Weightlifting coaches avoid the term "jump" when coaching their lifters. Telling a lifter who is spending all of their gym time perfecting one movement to jump may not get the desired results. There are tweaks and tinkering going on at a very complex level.

Now, take a group of teenage field or court sport athletes who have a limited training age and the word "jump" maybe the one cue that resonates with that young person. They know what the word jump means. They may not understand "pull with the fists" in enough time to improve performance.

Regardless, using a combination of verbal and non-verbal cues will most likely have the greatest effect on performance. In summary, coaches should:

- Use verbal cues that the athlete can relate to in regards to their sport.

- Use external, non-verbal cues. For example "push your feet and through the floor" or "punch the ceiling" as opposed to "push your knees out" or "head down." External versus Internal.

- Try to use tactile external cues when possible. Examples of these would be performing RDLs so the glutes touch wall behind the athlete or a coach using a band to pull the bar forward to help the athlete engage the lats and upper back in the first part of a pull.

The Context

Context may be the most important component of this argument. Applying the appropriate context shifts the debate about opinion to an insight into each situation. Not knowing context makes arguments invalid. I learned that the hard way with a great spring coach names Stuart McMillan and why I wrote How Do You Get Athletes Fast? Putting things in the correct context allows coaches to think outside of themselves which kick-starts meaningful dialog.

This section could be an article by itself, so I will try to consolidate my thoughts. This is something all strength coaches need to know. If you are saying things like this:

"The Olympic lifts have no place in sports performance."

You are not a very experienced coach and your ego is keeping you from fully understanding your ignorance and arrogance. Maybe you just aren't comfortable teaching them or you haven't seen a carry-over. Maybe you just don't have the time or resources to commit to instituting them in your program. Maybe they just don't have a place in your program.

At the same time, statements like this are equally as disturbing:

"Olympic Lifting is the only way to develop explosive power," or "You must use the Olympic lifts to get athletes better."

If you are making these kinds of statements, you are not a good coach. There I said it. Here's why.

To say that Olympic lifting is the only way or coaches must use them tells me that coach is not very experienced, only learned from one other person, or too lazy to expand their own knowledge base.

You, as a coach may feel it is the best method for your situation and that those movements are a staple of your program (even if it is personal preference). But, there are many ways to develop explosive power and there are athletes all over the world that physically improve without performing the Olympic lifts.

I feel there are several reasons coaches get "sucked in" to taking a side on this debate. All of these reasons have to do with making assumptions and forgetting context.

1. They assume everyone has the same facilities and equipment.

When I arrived at West Point, I was thrilled to know I have my own weight room for 7 sports. This was a few hundred athletes (Baseball, Softball, Men's & Women's Soccer, Wresting, Sprint Football, and Men's Golf). The 6,000sq ft ODIA weightroom had about six racks, two sets of dumbbells, two smith machines, and the rest of the room had plate-loaded machines and cardio equipment. Not one platform, not one bumper.

Now, I guess I could have told my boss and mentor that I could not train any of those teams without platforms or bumpers. I guess I could of told all of those sport coaches that their athletes would not be very explosive because of the facility. But, the fact was I needed that job. I learned so much in that year-and-a-half about what being a coach really means. No matter what resources you have, you must do everything in your power to physically prepare your athletes. You don't accept excuses as a coach, so you shouldn't give them either.

2. They assume everyone has the same time allotment to dedicate training toward these lifts. One more than one occasion, I have documented my frustrations I had when I was a strength coach at the Division III level. The scheduling and staffing situations always made things challenging. For some of the sports we worked with, we would train twice a week in the weight room and have an additional speed session in the off-season. Now, I would much rather train athletes 3-4 times per week, but I do feel that 2 days per week training can work. I outline that system in the Better Way to Train High School Athletes webinar.

If I made the determination that a sport was prepared enough to do so and they would reap the benefits of it; we would snatch one day and clean the other. In hindsight, maybe I should have chosen one or the other, but that's what we ended up doing.

For the most part, we would have two 60-75 minute sessions per week. When you factor everything else in to the training sessions, we usually had about 10-15 minutes for our Olympic movements. That could be less than 2 hours of training the snatch or clean over an 8-week period. Compare this to a competitive Olympic weightlifter and you can see why there is a discrepancy in skill acquisition between the two. Even our teams training 4 days per week may not perform Olympic lifts more than 2 of those days. Olympic weightlifting was only a small portion of the total physical development of the athlete.

3. They assume that all preparation includes the same methodologies. What I mean by this is the role that Olympic weightlifting plays in the preparation for your sport depends heavily on your sport. Vladimir Issurin separated these modes of preparation into 4 basic categories.

- Physical Preparation

- Technical Preparation

- Tactical Preparation

- Mental Preparation

The Olympic lifts are simply a means of physical preparation for the sport. They aren't even specific physical preparation. As Buddy Morris would say, any form of weight training is GPP for the sport. And, please don't get me started about GPP as it is one of the most misused terms in our field.

For a competitive weightlifter, performing the snatch is physical, technical, and tactical preparation. For a basketball player, it is a small portion of the physical preparation. Basically 1/3 of 1/4 of the total training for most sports. Another example is a Crossfitter who is performing the Clean. They are doing so to improve the clean. They are cleaning to get better at cleans regardless if that is for a 1RM or a longer set with a prescribed weight. However a lacrosse player is performing cleans to increase force development which will then carryover to the field (we as coaches, hope). This difference in the intention of training somehow eludes some strength coaches as we search for ways to highlight our athletes to quantify and justify our existence in the grand scheme of their development.

Olympic lifting is specific physical preparation, technical preparation, and even tactical preparation to the lifters who need to perform Olympic lifts in competition. To everyone else, Olympic lifts are GPP.

The Carryover

Finally, coaches need to be 100% sure that the implementation of Olympic lifting movements are solely responsible for the increase in power and athletic performance. By saying Olympic lifting is responsible for all of your athletes' improved performance you are implying that that on-the-field performance would not improve if the Olympic lifts were not present in the program. That's a bold statement.

I will say that there plenty of Olympic lifters who's vertical jump will increase simply be preparing for a weightlifting competition. Is that increase in lower body power enough to warrant a commitment to those movements? Probably. But, now you will need to start a whole new discussion on the correlation between the vertical jump and other performance indicators. As we all know, Correlation Does Not Imply Causation.

Adapting Olympic Lifting in a Sports Performance Setting

There are several adjustments that strength and conditioning coaches usually need to make in regards to their positions, progressions, and programming.

Positions

Teach the Athletic Power Position First

Try to use the same position and cues with minimal tweaks for all of your power positions. These can include jumping, landing, snatches, cleans, jerks, the catch position, swings, med ball throws, etc. Beside a variation in hand placement (obviously) and stance width, these positions should be relatively the same for athletes. Reinforcing one position makes more sense in terms of using your time efficiently as a coach. For a more detailed look and a video tutorial, check out Teaching the Athletic Power Position.

Starting Positions from the Hang or Blocks

I may be over-generalizing but high caliber Olympic weightlifters are not typically tall and lanky. Besides wrestling and gymnastics, the body-types of most of your athletes may vary from the best Olympic lifters. Now, before you list every Olympic lifter over 6ft tall, just understand that I am saying, in general, the bodytype that enables success in most sports may not be the same as elite-level Olympic weightlifters.

Whether this difference in anthropometric or due to poor mobility, some athletes just cannot achieve and maintain good positions. These issues are especially prominent in the starting position from the floor. Starting from the hang, blocks, or even a rack, can allow athletes to get into a more productive starting position.

Some Olympic weightlifting coaches will obviously prefer to start athletes from the floor and some still incorporate a top-down approach. Regardless of how you feel is the best way to teach the movements, take into account the specificity of the movement. Do you need to perform the Olympic movements from the floor? Know this answer and "why or why not" is important for all coaches.

Variations from the Hang

There are benefits from performing lifts from the hang position which outweigh the negatives. Anytime a coach would ask should an athlete perform the lists from the floor or from the hang, my standard answer is almost always...both. Here are some benefits:

- Athletes can perform these from a rack (as long as they are taught how to return the bar to the start position).

- Achieving the proper power position is almost always easier for beginners from the top-down as apposed to from the floor. There is a lot that can go wrong during that first pull to get the athlete out of position.

- The hang snatch and hang clean require a stretch-reflex which can have more similarities to sports specific skills. The ability to "stay tight" during the eccentric potion to generate force is a valuable commodity.

- The hang position permits a more fluent execution of multiple reps. This may require straps (oh no) or teaching the hook grip, but the benefits in grip strength fortitude are worth it.

Catching Weight in the Power Position

If I had my choice between an athlete catching the weight in a full squat position or some horrendous catch position I have often seen, then I would obviously choose the former. The problem arises in getting the athletes to that full catch position. More importantly, the rationale of a full catch becomes fuzzy in the realm of sports performance.

The catch position requires a great deal of coaching and often turns relatively good pull into an abomination of the lift. All of the technique issues leading up to this almost "unnatural act" of pulling yourself under at weightless bar further complicates the catch execution. As coaches, you get to the point where you almost don't mind seeing a straight-legged catch as opposed to the jumping jack catch or catching the bar on the lower pecs and performing a front rack good morning. Knowing that when the weight gets heavier the need for a strong catch position increases keeps driving coaches to spend a lot of time on this skill or catching the barbell. But is that time on the catch used wisely?

One of the elements of Olympic lifting that a lot of strength coaches (particularly from my experience, WSBB influenced and HIT coaches) do not like, is the catch. The argument is always, "Why not just capitalize on the triple extension?" Almost all coaches will tell you that generating force via the triple extension is the single-most benefit of Olympic weightlifting for athletes.

One of the issues I see with only doing pull variations is the simple fact that they are very difficult to regulate. How do coaches quantitative the pull when there are inconsistencies in height and modifications in body positioning (lowering the COG to the bar or not fully extending)? This makes cycling them or progressing them difficult. One solution that I read about over a decade ago was to institute the Targeted High Pull using Bands.

But, there are those coaches that preach the benefit and necessity of force absorption. I never got this. Someone will have to do a better job of explaining to me how catching a barbell will help me "absorb force" on the field. And, why do I need to learn to absorb force for contact sports. If you tell me the benefits of eccentric loading at higher speeds, then I'll start listening. Still, I sincerely believe there are better reasons for catching the weight. The best I have heard was from Jim Wendler. During a visit to elitefts with my interns, we had the infamous Cleans vs. High Pulls argument. The best thing he said was that with a Clean, there is finality in the lift. You either complete the lift or you don't. If you really think about it, not all movements can boast the same thing.

So, at the end of the day, I feel athletes should catch the weight in the Power Position. This position, if coached properly, will have the best carryover for athletic success due to

- This position is the same as the position the athlete is in before the second pull of any explosive movement. Repeatability

- This position will reinforce landing mechanics. Transference

Progressions

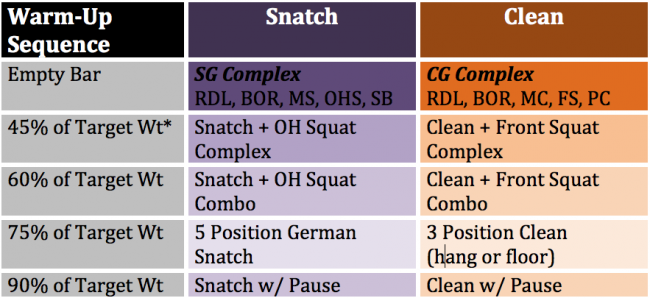

Structured Warm-Up System

In addition to a barbell warm-up complex specific to the snatch, clean, and jerk; we instituted a set-by-set sequence for each warm-up attempt before arriving at are programmed target weight for that day. I wrote about this warm-up protocol in Summer Training for Football (with 8-Week Program). One of the added benefits to this was the additional repetitions in the squat.

Using warm-up sets of Olympic lifts to reinforce squatting patterns is a concept we would implement. This would allow our athletes to perform squats at least three days per week to reinforce proper motor patterns.

Using the warm-up sequence to reinforce proper technique can be beneficial, particularly for younger athletes. For a more comprehensive look at how we implemented this, and other warm-up circuits, complexes, and progressions, take a look at Pre-Workout Circuits to Optimize Training Time and Maximize Performance.

Pauses

I am a huge believer in the implementation of pauses and mid-rep static holds for Olympic lifts specifically. I don't think anything connects verbal and tactile cues quite like pauses. The problem with the Olympic lifts is they happen too fast. The rate of force is why they can be effective in developing explosive power. But this also make it difficult for athletes to tell if they are "out of position" and for coaches to identify technique discrepancies. Like my friend JL Holdsworth says, "If [athletes] can't feel it, they can't fix it."

This concept was a staple in our training philosophy and help our athletes, our young coaches, and myself put athletes in a better position to improve at more rapid pace. One of the first articles I wrote was Olympic Lifting for Athletes: Using Static Holds to Improve Performance where I go into much more detail about pauses for weightlifting.

Lifting the Barbell Overhead

As many coaches that are proponents of athletes lifting weight over their heads (like myself), there are as many that don't want to take the chance of having athletes perform overhead lifts. Personally, I have never had an athlete injure themselves lifting a barbell, dumbbell or kettlebell, overhead. But, there is enough precaution that I don't blame a strength coach for not using an overhead press or snatch. I know these two movement are independent of each other, but for the sake of this argument, let's just lump them together. What is frustrating to me is when coaches will contradict themselves. Such as, pressing overhead is not OK, but by all means do heavy weighted dips. Also, if you look at wide overhand pull-ups versus the snatch, the hand placement is the same. I realize one is a closed-chained movement and one is open, but you are essentially in the same anatomical position.

The problem rears its head when a sport coach simply tells the strength coach, "I don't want them [his/ her team] doing anything overhead."

Your response will depend on your job security, but, like I said before, good strength coaches find a way to work around limitation regardless of who poses those limitations.

So whether it's the baseball coach or the athletic trainer be prepared to either justify your rationale of doing overhead lifts or concede knowing you will still adequately prepare their teams for athletic competition. For those who believe in overhead movement and want to "work around" these limitations, here are a few movements that you can "slip by" the naysayers.

- Landmine Presses (Half-Kneeling or Standing w/ Bands). The angle of the press is further out on front of the lifter due to the "arc" of the movement.

- Neutral-Grip Dumbbell Half Kneeling Presses. This movement limits the thoracic extension and the neutral grip keeps the hand closer and in a "safer" position.

- Hand-Stand Push-Ups. These require a progression (wall walks, pike on box, inverse, pad under head) but are great, humbling, strength builders. This is a closed-chain movement which the stabilization factor assists in consistent patterns.

- Neutral-Grip High Incline Presses. If overhead presses are outlawed, maybe the barbell bench press is as well. These can help substitute for both. Be cautious of overworking the front head of the deltoid and compliment this with posterior shoulder girdle work.

- 1 Arm Dumbbell Snatch. The only issue with this movement is it's twice the weight on the upper extremity and maybe not enough force developed in triple extension, especially if not done correctly. For a weightlifter, it's not a great exercise. For an athlete it could be. I wrote a detailed review on the 1-Arm Dumbbell Snatch that explains the execution and rationale.

- Kettlebell Snatch. The catch position of the kettlebell snatch is a little farther forward (at least initially). It can also be part of a swing, high-pull progression. We shot a tutorial on this progression along with some other kettlebell exercises called Kettlebell Training for Team Sports.

Programming

Volume Adjustments

This is a crucial component for sports performance coaches. Not only is it important to understand the appropriate volume parameters to optimize the training effect but also to fit into the time you have allotted for training. There are a couple guidelines for adjusting the volume for Olympic Lifts. For a more detailed look, check out Individual Training in a Team Setting.

As a general rule, we would like to have more sets than reps and most of the loading parameters and the rep scheme would be static. This second point is different from the strength movements where we would almost always use static weight with descending reps. Occasionally, we would use a static reps with descending weight scheme. Here are some of the Max Effort Cycles in a Team Setting we used with some success

One of the reasons I am content with flat-loaded volume for Olympic lifting only is due to the Time-Under-Tension involved, particularly for the pull phase. There is not much difference in the speed between 70 and 85% for a snatch. But a 15% increase in a squat means more work per rep and thus a reduction in total volume. I could be way off but we would keep the volume consistent when implementing Olympic Lifts with athletes.

A couple of set and rep schemes we utilized were as follows:

In-Season:

- 8 singles

- 5 doubles

- 3 triples

Off-Season:

- 10 singles

- 8 doubles

- 5 triples

For a more comprehensive look at adjusting volume during the season, take a look at Individual Training in a Team Setting.

We got to the point where we would adjust reps based on where the pull started from. Since muliple reps from the floor would look like clusters anyway, we would often just prescribe them as multiple singles with corresponding rest intervals.

- From the Hang - Triples

- From Blocks - Doubles

- From the Floor - Singles

Complexes and Combination Lifts

In order to keep the terminology consistent, we would use complexes and combination sets in the following manner. For example:

- Power Clean + Front Squat + Push Press Complex x3 =3 Power Cleans, followed by 3 Front Squats, then 3 Push Presses

- Power Clean + Front Squat + Push Press Combo x3 = Power Clean, Front Squat, Push Press, Power Clean, Front Squat, Push Press, Power Clean, Front Squat, Push Press

Some coaches, including myself, have a love-hate relationship with complexes and combination lifts. There is definitely an upside to implementing them as they may be the best tool to develop a work capacity while maintaining a relatively high power output. Unfortunately the overriding problem with complexes and combination sets is the simple fact that the variety of movements are limited to the same load. This negative attribute is exacerbated by individual athlete ability. What I mean is, not only is there a drastic 1RM discrepancy between the particular lifts in the complex but even more-so between athletes. Finding the best load to use to maximize the potential of each set.

Using set weights for these complexes are not entirely bad, especially for in-season work. Using a push press weight for the aforementioned complex can keep the power clean fast and the front squat weight light and fast enough to recover from. Here a a few we've used. Weight was usually static based on bumpers or we'd often use the "ladder" system to adjust weights. Snatch ad Clean would be caught in a power position.

- Snatch + Overhead Squat

- Snatch + Overhead Squat + BTN Push Press

- Snatch + Overhead Squat + BTN Push Press + Back Squat

- Snatch + Overhead Squat + BTN Squat Press + BTN Push Press + Back Squat

- Clean + Push Press

- Clean + Front Squat

- Clean + Front Squat + Push Press

- Clean + Strict Press + Push Press

A couple of side notes to using these complexes:

- We would traditionally not have our athletes perform a squat press (thruster) from the front.

- We could implement jerks into these complexes

- Some of these complexes would be from the floor and some from the rack (hang variations)

- We could add pulls at the beginning of the complexes to add volume

- We would manipulate volume by tweaking the reps within the complex i.e. 1 clean + 2 push presses + 3 front squats = 1

Pre-Hab Between Sets

I often get the impression from private sector coaches that they would have the ability to coach college athletes more effectively because they are more detailed with their instruction and coaching. One critical aspect to understand is that coaches an often be more detailed-oriented with they have groups of 3-6. I often observe coaches in the private sector and impressed by the amount of effort they put into their sessions. I honestly think they would run out of time if they coached in the same manner in a college or high school setting. They more athletes you have, the less time you have. Being able to combine phases of the training session can be the difference in a comprehensive training program and set getting through the workout. I recently wrote Are You Just Winging It? 4 Ways to Improve Your Training Session and filmed a webinar covering the same topic entitled The Four-Step Coaching Process.

One of the most effective ways of addressing the multiple components of athletic development with the time allotted is to assign exercises in between sets. Most of the time, it would be an explosive movement after a strength movement. Since we used our Olympic Lifts as our explosive movements, we would incorporate pre-habilitation or mobility exercises between those sets. Although we would reduce the rest time in between our Olympic sets, we wold still have time for several other exercises and still have time to change weights due to the size of the groups we normally had. Assigning ankle, t-spine, and hip mobility drills in-between sets immediately after the main movement can save time and have an acute effect on the subsequent sets.

For other ways to get more out of each training session, here are 5 Strategies to Perform More Work in Less Time.

Auto-Regulatory Training

There is a ton of information about the APRE derivatives and I certainly utilized this philosophy when I coached which I explain during this webinar, How to Implement Auto-Regulatory Training in a Team Setting. Without getting into a great amount of detail, we would used some rep and load ranges to allow the athletes to adjust week after week. The longest training cycle we could have was about 8 weeks, so our periodization schemes were more aggressive and more individualized.

In Summary

Overall, the Olympic lifts can serve as excellent training modalities to increase explosive power and enhance athletic performance on the field. It is most certainly not the only way or even the best way in certain situations.The strength & conditioning coach's job is to formulate a comprehensive training strategies based on the resources available and the profile of the athletes in regards to training cycle. Whether the Olympic lifts fit in that system is up to you. Just remember there is no right or wrong way as long as you are asking the right questions and you can justify your answer.

Articles by Mark Watts

Olympic Lifting for Athletes: Using Static Holds to Improve Technique

Head Games: Training the Neck to Reduce Concussions

The Fastest Sport on Ice: Things You Don't Know About Bobsled

Tips to Crush the Combine Tests

An In-Season Training Guide for Baseball Pitchers

Individual Training in a Team Setting

Off-Season Training for Football (with 8-Week Program)

What is Really Wrong with Strength and Conditioning

Sports Performance Coach Education Series

WATCH: How to Find a Strength and Conditioning Job

WATCH: Becoming a Mentor to Young Coaches

WATCH: The Four-Step Coaching Process

WATCH: 5 Strategies to Perform More Work in Less Time

WATCH: Why Communication is Key to a Better Coaching Career

WATCH: A Better Way to Train High School Athletes

WATCH: How to Implement Auto-Regulatory Training in a Team Setting

WATCH: Pre-Workout Circuits to Optimize Training Time and Maximize Performance

WATCH: Hypertrophy Circuits for Athletes in a Team Setting

Coaches Clinics

WATCH: Two Bench Press Mechanical Drop-Sets for Hypertrophy

WATCH: Two Lateral Speed Drills with Bands to Improve Change of Direction

WATCH: Adjusting the Glute-Ham Raise to Optimize Your Training

WATCH: Basic Linear Speed Acceleration Drills in a Team Setting

WATCH: Kettlebell Training for Team Sports

Mark Watts' Articles and Coaching Log

Thank you for sharing your knowledge.

Ezra