People have come to associate my writing with “block” periodization and the sport of powerlifting. While it may be a fair assumption as the first two articles I wrote had this in the title, I would actually venture to say I never really defined myself as this or as the authority on this principle. In fact, I am going to come out right now and say the first few articles I wrote had the concept wrong. I will explain where I am going with this in a minute, but also would like to use this article to show a set up that I have been using with success both on myself and also with training partners and online clients.

The Block Misnomer

Most of the block models floating around the internet or what people have described as block sequencing for powerlifting is sort of a hybrid of concepts that aren’t really in line with the true concept. First, block sequencing is used in sports with multiple qualities that must be trained for. The most classic example of this was Verkhoshansky’s models for track and field jumpers, which feature a strong emphasis on maximal strength as a precursor to qualities such as explosive strength among others that would make up the later blocks of training. However, in powerlifting, there really isn’t much more going on besides the development of maximal strength. And while we could argue that early blocks could feature different rep ranges or loading parameters to contribute to hypertrophy, work capacity, or other qualities, the only thing really being developed is maximal strength in reference to lifting weights.

What most of these models that are floating around demonstrate is a condensed version of linear periodization with a transition from general exercises to specialized or competitive exercises. I am just as guilty of this as anyone else, as this perfectly defines my initial article on this concept as well as my second article only differing by showing a greater load of competitive or specialized variants. What none of these models took into account was the idea of concentrated loading and delayed training effects, which define a model like Verkhoshansky’s Block Training Sequence. However, some of this still must be examined to see if this exact system truly applies to powerlifting in the truest sense.

The Next Revision

Within the last year or so, I began experimenting with rotating microcycles that worked on a 14-day rotation and featured concentrated loads for either the upper or lower body. I have a couple articles on this site outlining this principle. However, my idea behind this was to take the idea of concentration of loads to certain movements and consolidate them to certain periods of the microcycle. The purpose here was actually discovered almost accidentally. My first reason of doing this was to accommodate my schedule, which allowed myself only one day of training at a powerlifting gym and the other days to be at the school gym. Because of this, in the event of using gear I needed to make sure I could have spotters and help on that day, which would rotate between squatting in gear one week and benching in gear the second week. I could deadlift in gear at the school as I had no problem doing this without spotters, so this system came out of this original notion. Upon using it, I found that while the training initially would suffer toward the end of the concentrated week, by the time the 14-day period had concluded and it was time to begin a second microcycle, my ability to perform work both with more volume and intensity had increased. Upon examining the reason, it was due to a period of loading followed by a period of lesser loading the following week.

RELATED: The Importance of Tracking Volume

This concept isn’t anything revolutionary, as many systems such as Sheiko involve rotation of volume and intensity within each block to bring about this effect. However, the 14-day experimentation got me thinking as to what else could be done with this concept.

Concentrated Loading Based on Competitive Events

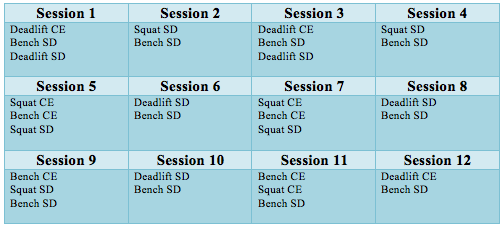

The next idea I had decided to try was both accommodating of my schedule as well as took the idea of concentration of loads to a greater level. With this idea, I was going to load one of the powerlifting events with a greater intensity and volume for one week out of a three-week block, with lower loads on the following weeks. In this system, I developed the following protocol:

Using this model, it is important to remember the following designations of the exercises:

CE – Competitive exercise. The actual squat, bench or deadlift with the technique that will be used in competition.

SD – Specialized developmental. Close variants of the competitive exercise, either broken into parts or with modifications to target specific segments.

SP – Specialized preparatory. Movements that work the muscles involved in the key movements of the sport. Does not have the same structure as the CE and is not necessarily a close variant.

There really were no preparatory movements, as I do not have a lot of time to dedicate to them. Other lifters I train with may have used more, but it was on their own time and not part of these sessions. For the most part, the SD movements for all of the blocks were either accentuated yielding/eccentric movements, lifts broken into separate parts, isometric holds at certain points in the lift, or greater range of motion exercises (either close stance/grip for squats and benches or deficit deadlifts for the pull).

For the loading parameters, each lift was trained with the following frequency in a weekly period:

Deadlift — Two to four times per week (four during Week 1, AKA Concentration Week)

Squat — Two to four times a week (four during Concentration Week/Week 2)

Bench — Four to six times a week (six during Concentration Week/Week 3).

To get an idea of how this worked, look at the deadlift. Week 1 would be the Concentration Week, which is performed with the highest amount of volume and intensity. Week 2 would have the lowest volume or intensity, which will depend on the individual. Week 3 would have a moderate amount of volume or intensity for this lift. The other lifts would follow a similar progression.

What I had noticed with this was the volume in general followed an upward trend from Week 1 to Week 3. For myself, this is because the deadlift responds to slightly higher intensities than squat or bench, but lower volumes. Squat and bench generally take higher volumes but a reduced intensity for me. Although as the program progressed I realized I might adjust this in the future as I tolerate squatting volume the best and too much volume beat me up in bench. However, to get an idea of the number of lifts in each week, I usually would have between 250–280 on a deadlift concentration week, 275–300 on a squat concentration week, and 300–325 on a bench concentration week. This counts the CE or SD lift that is over 50% of maximum.

Additionally, most weeks were set up with high, low, and moderate volume days. So in any of the weeks, the model could look as follows:

- Session 1: Moderate Volume

- Session 2: Low Volume

- Session 3: High Volume

- Session 4: Low Volume

In a week with 320 lifts, this may have gone as follows:

- Session 1: 84 Lifts

- Session 2: 68 Lifts

- Session 3: 108 Lifts

- Session 4: 60 Lifts

Results for This System

The best example of this system that I can use to give a result is a training partner of mine, Daniel Saez. Daniel is a raw, drug-free lifter who weighs a little over 200 pounds. Daniel came to our gym using a basic progressive overload system and had a meet shortly after joining. While he asked for advice, I told him to wait until after the meet to start a new program. My reasoning was two fold, as this would give us a baseline with his training and them allow us to use this system to compare results.

MORE: Verkhoshansky's 5 Rules from 'Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches'

At his meet at the USPA Europa in May 2015, he squatted 415, benched 275, and deadlifted 545. After this meet, he began using the system listed above, initially starting with a run through the 14-day microcycle block system for during the months of June and July. Following this, both he and I converted to the three-week concentrated loading method in August and ran four blocks from mid August to early November. The blocks went as follows:

Block 1 (3 weeks) — Yielding Emphasis

Block 2 (3 weeks) — Isometric Emphasis

Block 3 (3 weeks) — Shift toward exercises performed with competitive rate of movement.

Block 4 (3 weeks) — Reduction of volume, increase in intensity, beginning of competitive phase.

The plan was to initially include a fifth block that would serve as a taper leading up to a meet in early December. However, the location of the meet was changed so we decided to delay the competitive plans for a later date.

The first three blocks used submaximal weights, never exceeding 85%. We accumulated volume, and worked to increase the amount of sets at the more intensive percentages in each session (mainly 75–85% respectively). Block 4 was the initiation of the competitive cycle where we began to work up toward 90% of planned attempts and perform singles at this weight, with an overall reduction in volume and use of mainly the competitive exercise. The only other movements used here were overloaded exercises with the use of reverse bands. We did this after the singles at 90%, and used the same weight but performed two to three doubles. All other movements besides this were competitive exercises with 85% or less of maximum, for sets of two to three reps.

After conclusion of the final block and the decision to delay competition, Daniel decided to work up with no taper in training. He squatted an easy 495 (80-poound PR), benched an easy 355 (80-pound PR), and deadlifted an easy 600 (55-pound PR). These lifts look to be about 90% or so of his true maxes, so we know we are on the right track.

Some other observations here were the weights we had used initially in week one of the program were somewhat difficult, but had become very easily both physically and mentally as early as the following block. In fact, some of the weights we had used on the competitive exercise in the initial block which were difficult had become easy in more difficult variants. An example of this would be 80-85% of the deadlift being used for 12 singles in the initial session of Week 1 in a competitive stance deadlift from the floor. This was actually not easy and felt sluggish and difficult. By the third block, this same weight was being used for deficit deadlifts for 5-6 sets of three reps all performed with a stop/reset fashion.

Million Dollar Question: Is this really block periodization for powerlifting?

Since I started this off rambling about how block periodization really doesn’t apply to powerlifting, I will try to field this question as best I can. This model may be more in line of the concept of block sequencing which involves inducing fatigue, having an initial drop in performance, then having a delayed training effect brought on by manipulation of loading parameter to allow recovery. In this sense, the principles of the block models apply here. However, we are using these in a different way than the original intention. The idea of this came out of time constraints and the fact that most times when all of the lifts are given equal attention every week, it seems to actually result in more haphazard outcomes. In my experience, it seems the more multi-tasking that is done in any one session or week has always seemed to weaken the training effect. From using this model, it seems some of these issues have been alleviated.

What I had aimed to do was take the premise of the 14-day model, but create more directed training effects from each seven-day period. By consolidating more intensity and volume to one of the three competitive lifts, the training effect of each seven-day segment seemed to have a greater direction to improved results. So to say if this is exactly what I would consider “block” periodization is still up in the air. However, what I do know if it is definitely concentrated loading, and the effects of each seven-day period as well as each 21-day block have provided an interesting new way for programming each lift as well as sequencing blocks leading up to a test or competition.

toto strong

파워볼