Neck and Trap Training for the Strength Athlete

Training the musculature of the neck and trapezius is often ignored by many lifters. Aside from the occasional interset range of motion neck rolls and the two or three sets of shrugs haphazardly plugged into assistance work every now and then, the majority of strength athletes don’t devote much attention to training the neck and traps.We’re readily aware that neck training is required for those engaging in combat and contact sports. In combat sports, the neck must be able to resist foot and hand strikes by possessing adequate eccentric strength in all directions (flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and axial rotation). In contact sports, such as football and hockey, where the contact is intentional, and in sports like basketball and lacrosse, where the contact is usually incidental, having a strong neck is necessary to prevent traumatic injuries or fatalities. Following the torrent of concussions, strength coaches and healthcare practitioners are beginning to realize the value of neck training as a means to prevent concussions. Research has indicated that neck strength influences head deltaV and head injury criterion as well as concussion severity (1). Neck strength has also been regarded as a modifying factor in concussions (2).

Neck training has been long advocated by guys like Jim Wendler and Mike Ruggeria. However, I’ve been hard pressed to find many strength athletes who train their necks directly on a regular basis. In recent years, the concept of coaching and maintaining a neutral neck has swelled in popularity. Though many lifters aren’t training their necks with added load, they're still trying to achieve stability of the head and neck when performing numerous movements such as deadlifts, squats, and presses. In a neutral neck position, the lifter or athlete is coached to maintain capital neck flexion with cervical retrusion, which is simultaneously flexing the upper cervical spine and extending the lower cervical spine. In other words, lifters are told to keep the ears in line with the lateral deltoid and look forward with the chin slightly tucked. Often times, these lifters or athletes might exhibit a degree of forward head posture. Overactive suboccipital muscles, specifically the rectus capitis posterior major, and a taut levator scapula contribute to forward head posture. Coaching in absence of neck strengthening exercises that target the muscles that extend the neck (splenius capitis and splenius cervicis) and the deep cervical flexors (longus colli, longus capitis, and infrahyoid muscles) will do very little to help the athlete or client keep a neutral neck during heavily loaded movements.

Incorporating basic isometric movements such as chin tucks with the rear of the head pinned against the ground or a wall or from a quadruped position will be a good start. Once the neutral neck position is established, adding load such as isometrics performed against bands or against a Swiss ball or a corner Swiss ball bridge will help with neck and head positioning during compound lifts. Performing the corner Swiss ball bridge is helpful in teaching a lifter to keep his neck upright during a heavily loaded back squat.

[caption id="attachment_29924" align="aligncenter" width="331"]

Floor Chin Tuck[/caption][caption id="attachment_29925" align="aligncenter" width="136"]

Wall Chin Tuck[/caption][caption id="attachment_29929" align="aligncenter" width="261"]

Ball Chin Tuck[/caption][caption id="attachment_29927" align="aligncenter" width="275"]

Quadruped Chin Tuck[/caption][caption id="attachment_29928" align="aligncenter" width="212"]

Banded Neck Extension Isometric[/caption][caption id="attachment_29930" align="aligncenter" width="205"]

Banded Lateral Flexion Isometric[/caption][caption id="attachment_29931" align="aligncenter" width="329"]

Corner Swiss Ball Neck Bridge[/caption]For those engaging in strength sports such as powerlifting, training of the trapezius will differ slightly but distinctly. Strength and conditioning programs, particularly those dealing with football, put a heavy emphasis on training the upper trapezius. The upper trapezius is targeted via an arsenal of dynamic shrugging movements with barbells, dumbbells, and machines. Rightfully so, training the trapezius in this manner will reduce the strength and hypertrophic gains necessary to improve performance and stave off injury. However, if strength athletes train the upper trapezius as extensively or as frequently as athletes who partake in contact sports or combat athletes, it could alter optimal scapulohumeral rhythm, potentially lead to subacromial impingement, and overactivate the levator scapulae.

The upper trapezius (which shares proximal attachments with the middle and lower trapezius) along the medial part of the superior nuchae line and the external occipital protuberance, ligamentum nuchae, spinous processes, and supraspinous ligaments between C7 and T12 attach to the posterior superior edge of the lateral one third of the clavicle. The upper trapezius elevates the shoulder to neutral position by imposing an upward moment on its clavicuar attachment. This will drive the clavicle and scapula rearward, bringing the shoulder to a neutral position. Elevating the shoulders above a neutral position actually involves the sternoclavicular joint, as it will sustain downward loads applied to the lower limb. The downward loads will exponentially increase when the lifter grasps and pulls on an implement with appreciable load such as a barbell, dumbbell, or handles of a plate loaded or selectorized machine. When the shoulders are shrugged, with or without a load, the scapula is raised by rotation of the lateral one third of the clavicle through the sternoclavicular joint, allowing for the upward rotation of the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

Essentially, the upper trapezius works to stabilize the scapulae. The middle trapezius, which attaches to the medial margin of the acromion and upper lip of the spine of scapula, initiates retraction. The lower trapezius, which attaches to the medial end of the spine of the scapula lateral to the root, initiates scapular depression. Collectively, the trapezius muscles extend the thoracic spine by stabilizing the scapulae. An extended thoracic spine will help you lock out deadlifts, keep you from falling forward while squatting, and keep you tight on the bench.

One-armed constant tension band rows with rotation

This exercise is a mouthful. However, you can really lock your shoulder blade in place while opening up the subacromial space through the rotation.Start

Mid-point

Finish

I’ll position myself in a tall, seated position on the floor, keeping my hand firmly gripping the band with the thumb side of my hand facing down. My hand is actually facing and pulling from the point of origin. I’ll initiate movement with my shoulder blade, squeezing it back and down as hard as I can for a one-second count. Then I'll turn my hand, moving my wrist into a supinated position, while I drive my elbow past my shoulder. These can be performed from a seated position on the floor, on a bench, or in a half kneeling position. You may also position your arm 30 degrees from your body in the scapular plane to better recruit the mid and lower traps.

Constant tension banded dumbbell shrugs (not pictured)

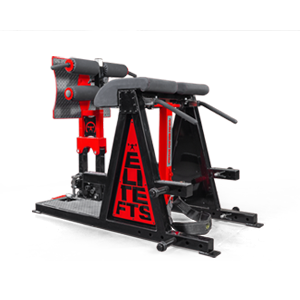

With this movement, you’re working to elevate your shoulders to a neutral position. Loop the band around the dumbbell twice, allowing for some slack in the band to create tension. Grab the bundle of bands and perform a shrug to neutral position. Hold for one second before returning to starting position. Repeat for desired number of repetitions or time.Clustered rack pulls from the knees

Perform the sets with 80 percent of the load you would use for your heavy deadlift work sets. If you’re performing doubles and triples with 500 pounds, put four plates on the bar.Start

Finish

Rack pulls performed in power racks or cages from pins or catches aren’t an exercise that will directly improve your deadlift. Rather they will reinforce scapular stability with a heavy load in hand. You’ll perform one pull, place the bar down, regroup, and pull again. You might have to keep your feet behind the bar, not under it, because you’ll have to create your own leverage when performing rack pulls.

Banded posture corrector farmer’s walks and shrugs

The posture corrector exercise, developed by Smitty, has been a staple in the programs of my athletes who are locked in atrocious posture throughout the day or who’s training or competitive demands require they operate in flexion such as throwing athletes, wrestlers, and cyclists.Walk

Shrug start

Shrug finish

I’ll add in a pair of moderately heavy dumbbells they can hoist and walk around. I’ll tell the athlete to lock his shoulders back and tell him to try to bunch his shoulder blades together and down. Although heavy carries have tremendous value in one’s programming, I feel as though they often pull the athlete into too much thoracic flexion, especially when fatigue sets in and/or when one’s grip fails.

Front squat holds

These can be performed with a clean grip or a bodybuilder style cross armed grip and held for time. I’ll typically insert these between sets of back or front squats, having the athlete or lifter unrack the barbell and hold it in place for 5 to 10 seconds. Alternatively, I’ve found these effective following a squat session, held for durations ranging from 20 to 45 seconds.

Many powerlifters don’t aspire to have large necks and obscene trap development. Typically, they both arise when handling heavy poundages session after session for years. However, if targeted training for the neck or traps is desired or warranted, it’s best to perform movements that won’t disrupt shoulder mechanics and might actually yield improvements in pressing, pulling, and squatting performance.

References

- Viano DC, Casson IR, Pellman EJ (2007) Concussion in the professional football: biomechanics of the struck player (part 14). Neurosurgery 61(2):313–28.

- Herring SA, Cantu RC, Guskiewicz KM, et al (2011) Concussion and the team physician. Med. Sci Sports Exerc 43(12):2412–22.