Kinesiophobia means “fear of movement”. Every coach knows about it. Coaches have known about kinesiophobia among athletes before research started to be done on it: kinesiophobia was a concern for chronic pain patients, particularly for lower back pain. Since athletes have a higher pain threshold level and higher pain tolerance, added to more risk-taking than risk-averse behavior, they have been mostly ignored by research for years.

Every coach has their tools to handle it in that secret little toolbox. The reason to be particularly attentive to kinesiophobia in athletes is that they won’t express it like non-exercisers and chronic pain patients. A disciplined athlete will just silently go into the octagon, to the soccer field, to the court or under the bar, perform the movement (with fear that they deny) and get hurt again.

Why? Because there is an unconscious reaction that will:

- Affect the overall balance and fluidity of the movement

- Affect the automated aspect of the technique and movement execution

- Provoke sudden muscle shortening/spasms

- Provoke sudden protective reactions that lead to injury

Let me share what’s in my toolbox:

- Study the movement. It may be something obvious but now you have a person in denial using those structures that you probably forgot about.

- Politely request contact with their physician and understand the injury, whether it involved surgery or not, as well as the recovery process.

- Go through the injury event in detail with your athlete/client.

- It is possible that you were there when it happened. If they were lifting and it’s an overuse injury, it’s harder to understand but the psychological response is the same. It’s important to identify the exact moment the athlete experienced the injury or became aware of it (the awareness moment is actually more important)

- If it was during a warm-up – in lifting, fighting, team sport drills, whatever – it is highly possible that your athlete was: (a) not really warmed-up or failed to do pre-activation drills prescribed by the physiotherapist; (b) was not paying attention. Seriously, that’s one of the most common reasons for injury during warm-ups; (c) it was an overuse injury and they became aware much later. That’s the worst-case scenario because the emotional reaction in the face of uncertainty and the unknown is fear and fear of fear.

- If it was during practice, there was a specific strike, move or weight in which it happened. Let’s consider the weight situation: your athlete suffered a bad muscle tear during a squat at 474lbs/215kg. Consider that weight the mental barrier. You will need to have a serious conversation with the athlete and the day he lifts this weight again he/she must be prepared. They must have lifted 452lbs/205kg for three reps several times with no pain. Then they must have lifted 463lbs/210kg for three reps with no pain, feeling good about it. Only then you will load 474lbs/215kg on the bar. When he/she lifts it, they will feel a moment of euphoria. It is possible they will try to persuade you to immediately go heavier. Bad idea.

Some examples:

1. My friend was a proficient capoeira fighter. During a “roda” (circle) with his training buddies, he was so careless that he left his face in front of his opponent’s foot (not supposed to!) and suffered a major jaw fracture. I should also mention that he was a bit high on weed. Who would play capoeira being high on weed? Someone who is over-confident. Over-confidence is a major source of injury. After that, he freaked out, went through the five stages of mourning, stopped smoking anything smokable and unfortunately stopped playing capoeira.

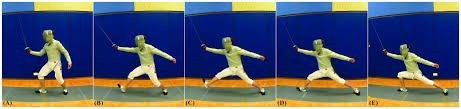

2. I was a child (I think 13) and a damn good fencer. In spite of my unfavorable anthropometric measures, Master (our coach) thought (but shared it only with my mother) that I was destined to be one of the great. It helps that I loved it so much that I don’t think I ever loved anything like it (except people). Two of my strong points were power/speed and incredible mobility. I had been a classical ballet dancer and had perfect and effortless split. Combined, they gave a huge reach to my lunge, always unexpected by the opponent given my diminutive size. One day I suffered a muscle tear on the left adductor during the lunge.

Fortunately, in my case, Master never made a big deal out of it. I don’t even remember how I recovered but soon I was lunging exactly as before. It did help that: (a) I had unconditional trust on Master. Even if he said something absurd, I’d assume it was true (he never did it because with great power comes great responsibility); (b) I saw adults suffering the same injury at several levels, from an “ouch, something is pinching here” to a damn scary scene where the big, strong male uttered a horrible scream, fell to the ground and clutched someone’s leg out of reflex.

3. A friend started feeling pain during the squats and then deadlifts. He was diagnosed with a cystic lesion at the acetabulum (femur/pelvis socket). It could be a lot of things. He chose a conservative approach and after steroid treatment and rest, we started to slowly work on the range of motion around the hip joint. Fortunately, he’s an emotionally stable man, a strength coach with exercise science training and a former fighter. With all the unknowns involved, we progressed through the movements until complete recovery of hip joint flexion and extension (squat, deadlift, lunge, walking around, jumping, living).

If you are an athlete, first, don’t be ashamed if you feel scared to resume the movement where you got hurt and don’t underestimate the “mental barrier”.

If you are a coach, all I can say is that sooner or later it will happen to one of your boys and girls.

PLEASE EXPLORE THE REFERENCES! They are great! There are only seven and you don’t even have to read more than one but do take advantage of this list.

References: