Introduction

I must emphasize that this is my perspective and opinion based on discussions, observations, and coaching experience.

I’m not a “speed guy.”

I’m not a “sprint guy.”

I’m a performance coach who works mainly with team sport athletes or athletes who aren’t sprinters. I’ve worked with every level—elementary, middle, and high school—along with collegiate and professional.

I’ve watched a lot of athletes move in a lot of different sports at a lot of different levels, and this is what I’ve found works for me.

If you’ve read my columns before, you know I’m very anti–“we’ve always done it this way.” If you’ve “always done it this way” but aren’t getting the results you seek, then it might be time to do it another way.

I see a field saturated with sprint “gurus” and sprint “coaches” selling false promises. They’re making a living selling speed programs, which are mostly just a bunch of silly drills with very little carryover into sprinting.

LISTEN: An Inside Look at a D1 Strength and Conditioning Program

For a performance coach, having a good understanding of sprinting is important, but sometimes we go too far in one direction and form biases. I want to present a simplistic guide on how to effectively run sprint programs for team sports.

The Problem

The problem is that it seems like there is a lack of respect for movement. Coaches are trying to take complex patterns and turn them into simplistic drills. Just because a drill looks like a sprint does not mean it transfers to a sprint.

The solution is simple.

Understand and respect the body as an extremely complex system, not some simple organism. I don't think enough of us give the human body, especially the brain, credit. It's smarter than you think. An athlete’s brain already knows the most efficient and effective way to move. Their brain knows more about what mechanics and power its body is capable of producing and handling better than any of us. It wasn’t until I truly understood this that I realized I should just have my athletes sprint and self organize—in other words, allow them to figure out what was optimal for them.

Sprint Drills

Sports by nature are random, chaotic, and unpredictable. I watch one athlete move and think I understand movement. Then, I watch another athlete move, and it’s completely different. This is one of the main reasons I’m not a fan of closed system drills and “mechanic” drills. I feel they should be used on an as-needed basis and as a last resort.

Early on in my career, I would spend 10-15 minutes on drills consisting of arm pumps, knee drives, “deceleration drills,” and a butchered attempt at A and B skips. Then, I rushed through five minutes of actual sprinting. I used these drills all of the time. They were in all of my athletes’ programs.

When I got into coaching, this is what I was taught to coach. Once I learned them, I not only coached them but also taught them to younger coaches. I was another coach who loved to do drills that looked really cool but in the end weren’t a viable solution to the problem I was trying to solve. I wanted to produce faster athletes.

All athletes have different limb lengths, joint orientations, muscle insertion points, movement restrictions, fiber type ratios, body fat levels, lean muscle mass figures, etc. All of this leads to various styles of movement.

I do think there is value in doing the Mach drills (A drills, B drills, and C drills) when they are done CORRECTLY, but many of us don’t know what they are, how to coach them, or how to progress them. The Mach drills are broken down into marching, skipping, and running. A-March, A-Skip, A-Run, etc. These drills were developed by Olympic Sprint Coach Gerard Mach for elite-level sprinters. They were never developed for technique work as many coaches claim to use them for. They were actually developed to specifically strengthen the muscles in postures and actions similar to those encountered during sprinting. The execution of these drills requires rhythm and tempos through a full range of motion to transfer. If you do use them and they aren’t constantly coached properly, you can potentially engrain bad habits/patterns, which end up being a waste of everybody’s time.

Sprint drills are useful only when they are really needed. Focused use over blanket application should be the approach you take when doing drills. They can be used to give athletes context about what’s supposed to be happening, but outside of this, your time is better spent elsewhere. Like sprinting. If you want to strengthen the positions that your athletes will be in, which can be done through intelligently programmed strength work, coach concepts, not drills.

Strength and Mobility

Most of the time, if your athletes can’t hit certain positions we are looking for in a sprint, they typically aren’t strong enough or mobile enough in these positions. If your athletes aren’t strong enough in the positions that you are having them drill, and if they don’t have the necessary ranges of motion in those positions, what’s the point of doing them?

Don’t go too far down the mobility rabbit hole, though. Many coaches I’ve talked to think that a lack of mobility in the hips and surrounding structures is an issue for a lot of athletes not being able to get into positions. They would then program 15-20 minutes of daily “mobility" work for their athletes. My first question is always, why have that in the program? Why do we think they lack mobility? Why are they tight? What’s causing the structures to tighten up? Does this tightness serve a purpose?

Athletes only need to be mobile enough to play their sports, not excel in a yoga class. Mobility is important, but if you aren’t strong or can’t control the range of motion, there really won’t be much carryover from just a few mobility drills. This is why I’m a fan of loading mobility drills and incorporating moves into the weight room that are outside of the sagittal plane but involve a full range of motion. Not only do we get mobility work but we also get strength work.

Although mobility work should be included in a program, just make sure that your athletes are also strong in those ranges of motion you are working on. This is why there should be a strength component. If your athletes are weak and immobile, their sprints will never look good no matter how many wall drills, arm pumps, marches, and skips you do.

Needs Analysis

Before you program for any sport, you should be doing a needs analysis. If you don’t know what this is or how to do one, check out this article.

Sports is Physics in Motion

Changing velocities is what every sport is based on. The athlete who can change velocities more effectively and efficiently will have an advantage over his or her opponent.

The goal of your training program is to get your athletes to produce as much force in the least amount of time and to have the ability to repeat this throughout their sports. Remember, though, that as velocities increase during a movement, the time to produce force decreases. This is why we need to get our athletes to produce the most amount of force in the shortest amount of time, AKA increasing the rate of force development.

Quick physics refresher:

Force is any interaction that when unopposed will change motion. Any change in motion requires the application of force. In sprinting, there is vertical and horizontal force production, and the phase of the sprint they are in will dictate the direction of force application.

Force = mass x acceleration

Acceleration is the rate at which an object changes its velocity.

The acceleration of an object is proportional to the total force applied to it and will be inversely proportional to the mass of the object. This means there is a direct relationship between force and acceleration when the mass is constant, which it is in sports, as our athletes’ mass figures don’t change. The only time mass will change is in the weight room.

Velocity is the rate at which an object changes position.

If you want to increase an athlete’s velocity, you need to either increase the time over which force is applied or the amount of force produced in a given time. When it comes to sports, we want to increase the amount of force produced in the least amount of time, otherwise known as impulse.

Although the amount of force that your athletes can apply is important, what is more important is the time in which the force is applied. This is impulse, and this is what is responsible for the change in velocity.

I am not going to discuss stride length and frequency. I feel they are a byproduct of force application and do not need to be addressed individually.

Phases of Sprinting and Mechanics

Which phase of the sprint your athlete is in will dictate the mechanics needed. Shin angles are where I’m usually looking at, followed by torso angles. The shin angle tells you how everything looks and where it’s pointed, and it’s where the athlete is going. If the technique looks “off” but is still fast, leave it alone.

Starting strength/Starts/First Step Efficiency: First five yards. Our athletes are working to overcome inertia and to get the body into an efficient position to accelerate. Because they are working with court and field sports, they don’t get the luxury of using blocks to start. The start comes from different positions and stances, which is why when doing sprint work you should utilize various start positions. Doesn’t matter the position; they need to be able to get into a proper acceleration position as quickly as possible. The more efficient the start, the sooner an athlete can accelerate.

Acceleration: 10-30 yards. A lot of coaches train their field and court sport athletes like sprinters, but there is a difference. Sprints have more time to accelerate. It’s a different animal compared with our field and court athletes. They need to be able to accelerate as quickly as possible. They don’t have time to build up like a sprinter does.

This is where team sport athletes need to excel. It’s what will set your athletes apart.

When looking at mechanics for acceleration, my eyes are on the shin and torso angles. In my experience, the greater the lean, the greater the acceleration. Around 45 degrees is what I’m looking for with the shoulders ahead of the hips and the hips ahead of the feet. Arms should move at the shoulder, and movement should be aggressive, as the arms help to increase the force application and stride rate, especially during acceleration. Push and punch are my favorite cues. You will commonly see low heel recovery along with longer ground contact time.

Both linear and lateral acceleration have the same shin angles.

Do not coach athletes to brace when running. The spine needs to be able to laterally flex and rotate along with the pelvis to run properly. Bracing typically won’t allow this. Strengthen the spine through its full ranges of motion as opposed teach “core” work where they are bracing and in place.

Maximum Velocity

This is when an athlete has reached his or her highest sprinting speed. I’ll argue that the majority of our field and court sport athletes don’t visit max velocity very often. This doesn’t mean don’t train it, but it’s on an as-needed basis. It’s very taxing on the body, so this leaves a lot of room for error and potential injuries, especially when it comes to work-rest ratios. I think that when it is used properly, incorporating top-speed sprint work into your program will have an effect on the entire acceleration profiles and speed reserves of your athletes.

For mechanics, athletes should be relaxed. Upright position with hips high. Arms still moving at the shoulder and hands relaxed. The foot should contact the ground almost directly beneath the hips and shins should be almost perpendicular. Heel recovery will be higher with less ground contact time.

Programming Guidelines

- Don’t overthink it, and keep it simple.

- Get strong.

- Improve elasticity.

- Strengthen joint ROM needed for sprinting.

- Sprint, and sprint often.

- Maximize recovery, and minimize fatigue.

Keys for Speed Development

- Apply force = max strength

- Apply force in less time = reactive strength

- Apply force through the ranges of motion required for their sport = mobility work

- Apply force in the right direction = angles (strength and mobility work)

Better force application means faster athletes. I’m still in the camp of athletes need to have a solid foundation of strength. No matter how much sprinting and technique work you do, if they aren’t strong, it doesn’t matter when it comes to executing when it matters most. Speed and strength go hand in hand. Strength training is only part of what makes an athlete successful, and remember that an athlete can never be too strong. It’s hard to become too strong, but it’s easy to become only strong.

True speed work needs to be done when the central nervous system is fresh and our athletes aren’t fatigued. The mistakes I often see with sprint programming is too much volume as well as too little rest and recovery. If your athletes are tired, how do you expect to get the training stimulus you are looking for? When we are developing speed, we are developing speed. A lot of coaches turn their speed sessions into conditioning sessions. If you want your athletes to be fast, they need to train fast, and to train fast, they need to have fresh nervous systems. Minimize fatigue, and always focus on quality over quantity.

When it comes to work-to-rest ratios, Mark Watts taught me 30-60 seconds for every 10 yards at the least. If the athletes aren’t recovering between sprints and look gassed, cut it early. When picking what exercises to use, think about the angles you are attempting to improve along with the phase of the sprint.

Look at what your athletes are actually doing in their sports. Why train 100m dash for football players if they don’t spend any time at those speeds? There are phases of sprinting, and you need to understand how long your athletes spend in each phase. If they don’t spend any time in a certain phase, why spend time training it?

In the private setting, we typically get 8-12 weeks tops to get an athlete ready at 2-3 days a week at one hour a session. So, when it comes to programming, I need to do what is going to give me the most results in the shortest amount of time utilizing exercises that will give me the greatest benefit along with exercises that can be used with various training ages.

“Deceleration” Training

Don’t train it. There’s zero reason for this. I don’t want my athletes to slow down and decelerate in their sport. I want them to be able to apply force and change direction. The argument for this is injury prevention or teaching force absorption (you can’t absorb force). Understand an injury occurs when the tissues aren’t strong enough to handle the load they are under. So, how is slowing down into a position going to prevent an injury when sports don’t happen in this manner? Most often, an athlete is running full speed, goes to make a cut and an injury happens. I used to train it, but it was short-lived, as I still don’t understand it’s purpose. Deceleration training 101: let them figure it out. Their bodies know what they can and can’t handle.

Aerobic Base

Programming aerobic work properly is often a forgotten component of a program. This is how we build a bigger engine for our athletes. When done properly, it can improve an athlete’s quality of movement, address weaknesses, and enhance their ability to handle greater workloads. Aerobic work isn’t crushing your athletes with some crazy mental toughness weightlifting circuit or running them until they puke. It should be based upon sound scientific principles.

Without a solid aerobic foundation, the ability to improve other performance qualities will be reduced. What’s great about aerobic work is it’s compatible with hypertrophy, strength work, speed, and even power work. You may be wondering, “Why would my athletes need to train their aerobic system? They aren’t running cross country.” Having a well-functioning aerobic system allows your athletes to have increased oxygen availability, which allows training to be less fatiguing on their body. They will also be able to complete tasks with a lower heart rate, which in turn will allow them to train at higher intensities. More work with less energy. Higher power output levels for a longer duration.

Another great thing about having a higher aerobic capacity is that your athletes will have an increased ability to recover. Without the ability to recover their body won’t repair, which will limit their progress and performance. Remember that the residual adaptations from aerobic development last up to 30 days, so when we finish our GPP/aerobic block, we only need to revisit every four to six weeks, and I usually do this during a down week.

This is why conjugate works so well. Have your athletes perform their aerobic work utilizing tempo work or work performed in interval fashion. Just think outside the box a little bit. I've used medball work, sprints, the Prowler®, carries, sled drags, battle ropes, etc. Don’t do steady state with your athletes. Nobody likes steady state, especially a team sport athlete. Tempo work is the best solution to this problem. It allows your athletes to perform aerobic work in interval fashion. And since they are low intensity, they can be performed pretty regularly. You just need to ensure that it is performed in Zone 2, an RPE of 6-7, or a heart rate percentage of 60-70% of max heart rate.

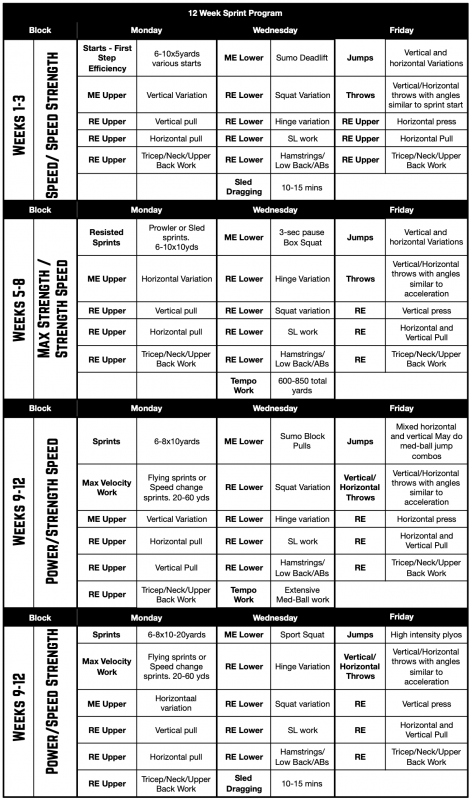

12- Week Sprint Program for a High School or College Athlete

Closing

The best athletes create the most force from multiple angles utilizing the most tools. Your job as a coach is to give them those tools to accomplish this. Trust that your athletes will put it together.

What I’ve learned is you should always be evolving. Don’t be too biased either way. Some of us are pure strength coaches, others sprint and speed, whereas the best option is somewhere in the middle combining it all, as there are plenty of options available to get your athletes better. What’s worked for me is mixing methods to address multiple areas. Sometimes speed is what an athlete needs, other times its strength, and sometimes it’s both.

Nobody has this figured out. What I’m presenting is what’s worked for my athletes. It’s based on principles involving anatomy, biomechanics, physiology, psychology, and neurology along with 10 years of experience coaching. Take 1-2 things from this article and implement it. See what works for you and what works for your athletes. This is one of the greatest parts of this field: the weight room is our laboratory, and results speak.

What’s worked for you and your athletes?

Header image credit: Liu Zishan © 123rf.com

3 Comments