An Introduction to RPR

For those who are unfamiliar, over the summer there has been a buzz in the strength community regarding the performance benefits of Reflexive Performance Reset (RPR). As many of you have likely read Dave Tate’s personal accounts or JL Holdsworth’s experience taking and utilizing the technique on Dave and other athletes, this publication will serve to provide yet another outlook on RPR. This will be a more in-depth look at the physiological processes that occur in the body due to stress and overtraining and the concepts that RPR utilizes to address them.

After almost seven months of implementation at my facilities and at the University of Memphis, Reflexive Performance Reset has been a game changer for a wide variety of athletes, coaches, patients, and even myself. So long as the subject is willing to do what is asked of them both inside and outside my office, RPR has batted 1.000. EVERY person that has implemented RPR into their training or life has seen positive effects in strength, performance, and/or pain. In my practice and on the field, I utilize multiple tools to help get my athletes performing at their peak potential. This includes adjustments, dry needling, myofascial release/ART, kinesiotaping, and various types of rehabilitative exercise prescription. RPR is without a doubt the most effective method I have encountered for addressing compensatory motor patterns and restoring proper motion for enhanced performance and function. So now that I have your attention, let's get down to the nitty-gritty on how RPR gets the job done.

The Importance of the Nervous System

Reflexive Performance Reset involves manual strength and flexibility testing to assess the recruitment level and motor patterns of the muscles that drive movement. This assessment allows for the identification of compensations that develop due to chronic stress and act to accomplish a given movement or task. The nervous system is by far the most influential physiological system in our body. It is a system that allows us to regulate, move, sense, think, and essentially live. It is the central control system that has superiority over all other physiological systems in our body.

RECENT: Finding Strength: Reflexive Performance Reset

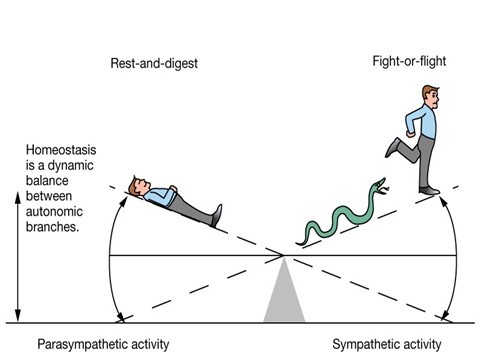

Compensations in the neuromusculoskeletal system are subconscious in nature. These compensations can be the result of excessive stimulus from the internal (injury, excessive joint forces and instability, etc.) or external environment (work, social life, etc.) causing chronic excitement of the sympathetic or “fight or flight” response. That means that not only do you not sense these processes, you also cannot control them with a simple cue or by watching a video.

Image courtesy of reflexiveperformance.com

This could be a major reason why, from a strength coach's perspective, there’s frustration with trouble clients who just can’t quite fix their weak points and imbalances. You may be hammering every correct glute exercise, providing the knowledge and cuing to perform that exercise properly, and still find that your athlete is contracting the hamstrings or low back while their ass is still like a bowl full of Jell-O. Regardless of how many times you tell that person to squeeze their glutes or put them into a glute isolation exercise, if the body’s motor pattern has compensated to drive hip extension with the hamstrings, hamstrings are what you’ll get.

The fight or flight response is a normal adaptation that occurs in the body. When subjected to stressors or threats, the sympathetic nervous system kicks in. This results in increased blood pressure, respiration, cortisol release, etc., in order to handle this stressor. This reaction to stress is normal and is meant to allow for a short-term “boost” in order to adapt to a stressor and survive. Think of a sympathetic response as the gas pedal when you are trying to pass another vehicle. Once the stressor has passed, the body’s parasympathetic nervous system increases in tone, which returns it to a normal, rested state. Think of the parasympathetic response as a “brake.”

Under normal circumstances, this adaptation can be quite beneficial. Let’s say you are walking through the forest and you cross paths with a bear. A stimulus occurs, the body temporarily hits the gas pedal, causing an increase in heart rate, breathing, and resting membrane potentials in nerve cells. The body is primed for an all-or-nothing battle or sprint away from the bear. At this point, nothing matters besides survival from this stressor. Once the threat of the bear is over and the stimulus is clear, the body returns to its normal state without much alteration in normal function. Because its origin comes from the need to survive during life-threatening situations, the sympathetic response is only beneficial when short-lived.

Fortunately for our species, we have evolved to a position where these life-threatening situations are few and far between. Unfortunately, this same stimulus from the bear encounter is mimicked in our everyday stresses from work, social life, athletics, etc. This means that the average human living in the 21st century is stimulated to enter this “fight or flight” response on a regular basis.

This chronic sympathetic state is much less favorable than the acute spike and return to baseline example with the bear. Again, because these stressors are a constant bombardment in our daily lives, the body is unaware of when the stressful stimuli will subside. This makes it impossible to return to normal and causes the neuromusculoskeletal system to look at long-term solutions to survive. There is an increase in resting heart rate, labored (chest) breathing, and the development of compensations.

When this occurs, long-term survival becomes a priority for the neuromusculoskeletal system. This priority demands energy prioritization and efficiency in an attempt to outlast the threatening stimulus. After a long enough period of time, this survival state can become the new “normal” and the body’s equilibrium shifts toward a more sympathetic state. Adaptations in the neuromusculoskeletal system favor energy efficiency over force output and joint stability. In this scenario, the choice is to utilize accessory muscles over prime movers to accomplish movement. The immediate effect of this change is minimal, as an athlete’s uncanny ability to “get the job done” will still allow his or her body to function at a high level. In the long term, however, this athlete is set up for future injury. This is akin to watching a cheetah chase a gazelle. The gazelle may be full-out for minutes without any end in sight when suddenly it stumbles and collapses because it has literally run its body into the ground.

MORE: How Dave Tate Is Setting 90-Pound PRs

The compensatory patterns or “drivers” that are identified using RPR are a direct result of this chronic "fight or flight" stimulation and are highly influential in the long-term performance and health of the athlete.

RPR and Sports Performance

RPR’s performance improvement is accomplished through enhanced neuromusculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory function. The goal of RPR is to prime the athlete to be as stable and explosive as possible. This is accomplished through identification of each individual's "driver" and stimulation of specific points on the body to reset the nervous system. By utilizing RPR, we are hitting the brakes on the sympathetic nervous system and restoring the body to a state of parasympathetic drive. This return to parasympathetic drive leads to a few changes that affect the bottom line of performance.

The first change is an increase in cardiorespiratory efficiency by restoring proper diaphragmatic breathing. A chronic compensatory pattern often seen in today's society is labored or "chest" breathing. This is a method of breathing in which inspiration is mainly driven by contraction of muscles in the neck and chest in order to draw air in at the apex of the lungs. This is inefficient, as energy must be spent on each breath of inspiration and the volume of air inspired is decreased.

Diaphragmatic, or normal breathing, allows the lungs to expand and inspire passively without wasted energy. Diaphragmatic breathing is characterized by breathing through expansion of the abdomen. This allows the diaphragm to lower, causing a significant increase in lung volume and surface area compared to chest breathing.

Diaphragmatic breathing is also known to stimulate the vagus nerve, which is a major driver of the parasympathetic nervous system. Because of this positive feedback loop with the vagus nerve, proper breathing is the single most important drill to practice and is encouraged throughout each session as well as in everyday function.

Finally, diaphragmatic breathing leads to increased stability of the lower back, which subsequently allows for improved hip mobility. This helps break the cycle of lower-crossed syndrome that is seen in a large portion of the population.

Once breathing is addressed, performance maximization is accomplished by emphasizing the restoration of normal movement and proper motor patterns. In a state of compensation, accessory muscles rather than prime movers are utilized to induce force. This decreases the amount of force the body can produce, as it is not effectively beginning a movement by firing biggest prime movers. Since accessory muscles are often used more for joint stability, joints become less stable when accessory muscles are asked to drive movement. As energy is created and transferred through the kinetic chain, a percentage of this energy is lost in each joint that is unstable. This means joints are constantly absorbing more and more wear during movement, which sets the stage for future injury. This is literally adding insult to injury.

In a normally functioning body, all force and movement is created through hip extension or hip flexion. The prime movers of hip flexion or extension disperse these forces away from its center of mass and outward towards distal joints in the kinetic chain. The transmission of these forces is continued by the distal joints’ prime movers and eventually to the external environment. Since accessory muscles are properly focused on joint stability in a normal scenario, very little force is lost across this dispersion of forces and the body can transfer a maximal amount of force to the external environment. This pattern resembles a bomb explosion and serves as the most efficient and powerful means of creating and applying force. This is the pattern that RPR looks to restore in order to facilitate a better, healthier athlete.

Who can benefit from RPR?

Reflexive Performance Reset is a methodology that is most geared towards a performance enhancement purpose. Therefore, the most obvious application is with the competitive athlete. In reality, though, anyone working to increase their own personal performance is a great candidate for RPR.

RPR is a very useful tool for strength coaches, athletic trainers, and health care professionals who work with athletes, patients, or clients on a performance basis. The purpose of this tool is not to treat any illness or disease. Its purpose is to identify problems and compensations in an individual’s movement patterns and to restore neurological balance to allow the body to perform the way it naturally should. This methodology is also geared towards the athlete itself. As one of its strongest points, long-term effects are dependent on the athlete to continue performing specific Wake-Up Drills. Wake-Up Drills serve as a “cruise control” to the initial reset done by an RPR trained individual, allowing the athlete to maintain for extended periods of time. These drills also allow a sort of snowball effect, as an individual who is driving movements using proper motor patterns will reinforce those motor patterns the more they move and train.

Currently, Reflexive Performance Reset holds teaching opportunities for strength coaches, personal trainers, health care professionals, and athletes. These hands-on seminars are set at different levels to accommodate the needs and level of understanding of an athlete compared to a strength coach or health care provider. Currently, there are seminars available across the United States and they often sell out quickly. For more information on RPR, visit www.reflexiveperformance.com.

Dr. Tyrel Detweiler provides care for athletes across all sports with a majority of his experience coming from working with athletes in collegiate and strength sports. He holds a doctorate in Chiropractic and a Master’s of Science in Sports Rehabilitation. He is the owner of Mid-South Spine and Sports Performance in Cordova, TN. This facility has a unique relationship with NBS Fitness, giving him access to some of the best strength athletes in the Mid-South. He was a former member of Mizzou’s Sports Medicine Team and is currently in his second year as the chiropractic physician for all University of Memphis Athletics. Tyrel was a college football player at the University of Iowa and has competed in powerlifting and strongman since 2010. He is also the current Mississippi state representative for United States Strongman. He can be reached at drdetweiler@midsouthssp.net.