Introduction

These are intense and confusing times in the debate and intervention on sexual violence, both as public safety and public health issues. Never, as now, have we been exposed to so many domains where sexual interactions are a means of inflicting pain, intimidation, and exerting power. Never, as now, have we faced so much controversy on what consists the basic concepts that we require in order to promote a productive debate. Solving a problem requires us to understand the problem. In modern society, science is our basic tool to understand reality and problems of any nature. The goal of this article is to provide tools to understand, prevent, and act on the problems of sexual violence, with a focus on the coach-athlete interaction. As such, there is some review of the technical literature, statements from public organisms, and a list of resources for victims, administrators, and for more information.

As a disclaimer, I’d like to point out that no matter the neutrality and serenity of the tone adopted in the article, if you or your loved one have been victimized by sexual violence, the content can trigger memories and feelings. If you feel this is something you shouldn’t be exposed to now, stop here. You may want to skip to the “resources” item or even seek support by yourself.

Words can hurt, even if they are supposed to help. If something is buried deep in some dark corner of your mind, there is a reason for that. Handle with care.

Parts

- What Sexual Violence Is and Why Researchers Think It Happens

- Epidemiology of Sexual Assault

- Sex and Power in the Coach-Athlete Relationship Context

- Coaches as Violence Prevention Advocates

- Prevention: What Can Be Done and By Whom

- Sexual Violence PTSS/PTSD and Its Treatments

- The Importance of Network Support

- List of Resources and More Information

- References

- Justice, Coping, and Recovery for Victims of Sexual Violence — written by Samantha Coleman

What Sexual Violence Is and Why Researchers Think It Happens

The reason this topic is here is not mere academic curiosity. One of the things victims most often ask, at some point in their journey, is “Why was this done to me?” It is important to address it, especially because this question, whether consciously or not, may lead to wrong answers, guilt, and shame, such as “I probably invited it”, “It was because of the way I dressed”, “Maybe he didn’t know I didn’t want it”, “I deserve it”, “I’m stupid and trusting” or other similar self-deprecating thoughts (Wilson et al 2017). Sexual violence does not happen for any of these reasons.

Sexual violence is not one single social or psychosocial phenomenon, but rather a set of phenomena that result in the same outcome. The shortest definition is the one adopted by the Center for Disease Control (CDC): “Sexual violence is defined as a sexual act committed against someone without that person’s freely given consent” (Basile et al 2014). Sexual violence is divided into the following types:

- Completed or attempted forced penetration of a victim

- Completed or attempted alcohol/drug-facilitated penetration of a victim

- Completed or attempted forced acts in which a victim is made to penetrate a perpetrator or someone else

- Completed or attempted alcohol/drug-facilitated acts in which a victim is made to penetrate a perpetrator or someone else

- Non-physically forced penetration which occurs after a person is pressured verbally or through intimidation or misuse of authority to consent or acquiesce

- Unwanted sexual contact

- Non-contact unwanted sexual experiences

The World Health Organization's (WHO) definition emphases the aspect of coercion; sexual violence would be any act or attempt of sexual nature in a coercive context (WHO 2002).

Still, the question remains: why does it happen? Sexual violence is as much a class of violence, or aggression, as it is a form of sexual act. If the great majority of individuals do not engage in sexual aggression, and with the wide range of opportunities for consensual sexual encounters in the modern world, why do some individuals do it? There can be no universal answer to this question, as we are not dealing with one single phenomenon, but some items will always be present. In studies concerning male sexual aggression towards women, these are some predictors (Malamuth 1986):

- Dominance: Among convicted rapists, some of the types are the power rapist, the anger rapist, and the sadistic rapist. Since the majority of sexual predators are not even reported, this population provides an opportunity to study motivational elements that might help understand a much more widespread phenomenon. The desire to conquer and sexually dominate the victim seems to be important.

- Hostility against women or acceptance of violence against women: Among convicted rapists, those with the highest levels of hostility against women become aroused by their suffering and fear, whereas non-hostile men tend to feel discouraged under the same circumstances. Belief systems that condone violence against women (or other groups) also are considered a factor in sexual violence.

- Antisocial personality characteristics: Or psychoticism are often present.

- Sexual experience: If social factors such as a positive valuation of “conquest” as a measure of self-worth are present, predisposed sexual aggression is more likely.

Males are also raped and these offenses go even more frequently unreported than female rape. Actual data involving male rape have such huge variation (from two percent to 20% in the same population, different studies) that it is fair to say much more research is needed. Two methodologically difficult to research situations (and even more heavily veiled by taboo), where sexual violence against males happen, are prison and war (Beck et al 2013, Modi et al 2015).

Unfortunately, that doesn’t help much to answer most victims’ personal question: why me? There is plenty of research about sexual choice and mating preferences among humans, but as most authors stress, sexual violence is less about sex than it is about violence. Either you were in the wrong place and the wrong time to interact with a dominance assertive predator, or you were just in the wrong place in the wrong time. If it weren’t you, it would be somebody else. Even the most “groomed” victims (see below) are usually one among many.

The takeaway here is that it is never your fault and it is not about you. You were caught in the performance of an individual or socially pathological behavior. You didn’t do anything wrong.

Epidemiology of Sexual Assault

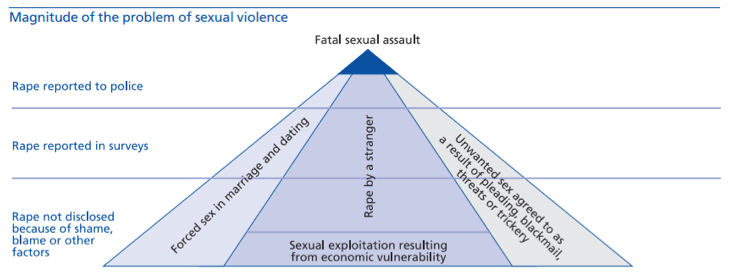

Unfortunately, we actually don’t know as much as we should about sexual aggression because most of it never comes to light. According to RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network), these are the rates of rape underreporting: Only 310 out of every 1,000 sexual assaults are reported to police. That means that about two out of three go unreported. Of individuals of college age, 20% of female students report and 32% of female non-student report. Of the elderly, 28% report. Of members of the military, 43% of female victims and 10% of male victims report.

This is approximately what we end up with:

Fig 1: The magnitude of the sexual violence problem. From WHO 2002, p. 150.

According to RAINN, the reasons for not reporting sexual violence are the following:

- 20% feared retaliation

- 13% believed the police would not do anything to help

- 13% believed it was a personal matter

- 8% reported to a different official

- 8% believed it was not important enough to report

- 7% did not want to get the perpetrator in trouble

- 2% believed the police could not do anything to help

- 30% gave another reason or did not cite one reason

Other reasons include (Kilpatrick at al 2007):

- Reported to a different official

- Did not want family to know

- Did not want others to know

- Not enough proof

- Fear of the justice system

- Did not know how

- Feel the crime was not “serious enough”

- Fear of lack of evidence

- Unsure about perpetrator’s intent

Of what we do know, the numbers are staggering (Black et al 2011). In a nationally representative survey of adults:

- Nearly one in five (18.3%) women and one in 71 men (1.4%) reported experiencing rape at some time in their lives.

- Approximately one in 20 women and men (5.6% and 5.3%, respectively) experienced sexual violence other than rape, such as being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, unwanted sexual contact, or non-contact unwanted sexual experiences, in the 12 months prior to the survey.

- 4.8% of men reported they were made to penetrate someone else at some time in their lives.

- 13% of women and 6% of men reported they experienced sexual coercion at some time in their lives.

In the same survey:

- Among female rape victims, perpetrators were reported to be intimate partners (51.1%), family members (12.5%), acquaintances (40.8%), and strangers (13.8%).

- Among male rape victims, perpetrators were reported to be acquaintances (52.4%) and strangers (15.1%).

- Among male victims who were made to penetrate someone else, perpetrators were reported to be intimate partners (44.8%), acquaintances (44.7%), and strangers (8.2%).

Although public health organisms have been investing in health education concerning this matter for years, most people are still under the impression that sexual violence is more likely to happen when the perpetrator is a stranger. Actually, the stranger is the less likely perpetrator and it is important that this information is widely known. The person who is going to sexually attack you is more likely to be your neighbor, your friend, your uncle, your adviser, or your coach than the weird guy in a grey hoody.

That highlights one of the highest risk situations for sexual violence: drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA). The real extent of DFSA is not known and is difficult to study (Juhascik et al 2007, Kilpatrick 2007). Many drugs are known to be employed by perpetrators to cause victim sedation, submission, impaired judgment, inability to defend themselves, and/or amnesia. DFSA seems to be involved in a large proportion of acquaintances perpetrators sexual violence cases, which is the second most common class among females (40.8%). There are two basic forms of DFSA: proactive DFSA, when the perpetrator administers the drug to the victim (either in covert or forced manner), and opportunistic DFSA, when the perpetrator takes advantage of the victim’s state of profound intoxication to engage in sexual activity. The definition usually attributes the opportunistic DFSA to voluntary drug consumption on the part of the victim (Anderson et al 2017).

Public opinion frequently withholds support to victims of opportunistic DFSA sexual assault. After all, “What were they thinking, drinking that much?" Not so fast. First, frequently, high levels of intoxication are a result of active encouragement on the part of the perpetrator. Second, in many jurisdictions, intoxication is a consent-negating circumstance. Third, self-reporting is an unreliable criterion (Juhascik et al 2007). Was it the beers that you had? Was there something in the beer? Do you remember having taken anything else? Of the reported sexual assault cases, Juhascik and collaborator’s study (2007) showed the proportion of DFSA to be anything from 30% to 60%.

These numbers should help you understand that it is never the victim’s fault. Celebrations involving alcohol are part of our culture and becoming inebriated is no excuse for taking liberties with a victim. Unfortunately, it is one of the reasons victims frequently fail to report or even talk about the sexual violence they suffered: shame. Actually, if the victim is inebriated, that is a reason to not touch her even if she fails to deny consent, given the reasons above.

Sex and Power in the Coach-Athlete Relationship Context

At this point, it must be clear that sexual violence involves power asymmetry of some kind. Coercion can only be exerted under such conditions. Examples include:

- Adult and child

- Adult and elderly person

- Man and woman (on average, men tend to be physically stronger and capable of exerting dominance over women)

- Person with a weapon and person without a weapon

- Anyone and an inebriated, poisoned, or unconscious person

- Anyone with the power to fire, hire, punish, or who is in any way a hierarchical superior, and a subordinate

- Anyone and a mentally ill individual

- Person in a position of authority, celebrity, or otherwise higher status, and someone out of that position

There is ample literature about the role of sports coaches in children and even adult athletes’ lives. Coaches are, first of all, authority figures by definition. If we are considering male coaches and female athletes, which is what I am doing in this item, we have two power asymmetry elements in the pair. That is our starting point: the male coach and female athlete relationship is asymmetric by definition (Tomlinson and Yorganci 1997). This is not a value judgment; in all merit-based endeavors, there is power asymmetry. How we behave within such asymmetric conditions is the real issue.

Research on sexual violence is relatively recent, starting to grow in the 1980s (Brakenridge 2000). Soon, a shocking number of cases involving years of sexual abuse by male coaches over young (starting as children) female competitive athletes emerged. Today, the number of high profile cases of sexual abuse involving female athletes grows exponentially. The reason they become so shocking is that, frequently, it takes years for enough evidence to be gathered against a perpetrator in order to encourage victims to come forward. There is always too much at stake for them. Given the gravity of the situation, the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) Board of Governors adopted this year a new policy that requires all of 1,123 NCAA member schools to complete annual sexual violence prevention education.

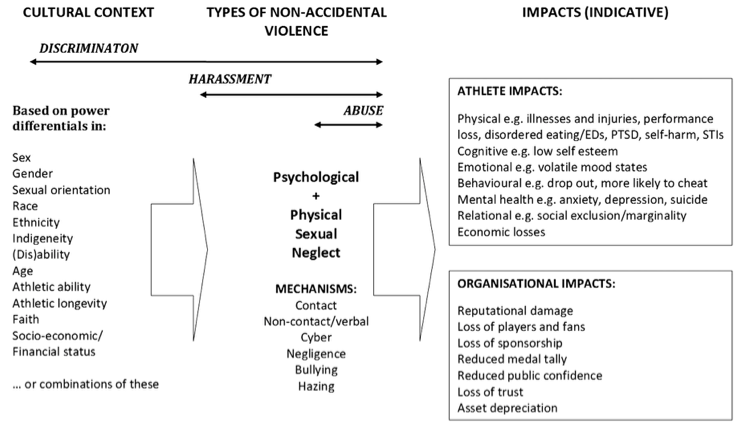

The year before, the Olympic Committee also released a consensus statement regarding harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport (Mountjoy et al 2016). There is a detailed analysis of the power asymmetries conducive to violence situations. Figure 2 summarizes its conclusions.

Fig 2: Conceptual model of harassment and abuse in sport showing cultural context, types of non-accidental violence, mechanisms and impacts. ED, eating disorders; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; STI, sexually transmitted infections. From Mountjoy et al (2016).

Brackenridge (2000) explores predictors of inappropriate sexual conduct leading to violence in her review. One important factor seems to be “boundary erosion”, where there is increasing disparity in the perceptions of both parties concerning what is acceptable and what isn’t. She mentions the “grooming process” by which the perpetrator secures the victim’s cooperation. At the core of this concept is the issue of trust. Trust is necessary to construct authority and is also necessary for the athlete’s full commitment to the training regime. Trust may or may not lead to intimacy. Coaches are frequently referred to as surrogate parents. It is not infrequent for coaches to end up developing a romantic relationship with their athletes and marrying them.

The problem is that in the context of competitive sports, especially collegiate and professional sports, there can be situations where trust leads to sexual interactions that are hard to even identify, given the nature of the relationship. This is what Brake (2012) calls the “dirty little secrets of sports.” The legal scholar remarks that in spite of all the regulations introduced to deter sexual violence, the measures ignore “the inherent vulnerability in the relationship that makes meaningful consent impossible” (Brake 2012). It is not rare for sexual violence cases to be revealed long after the athletes retire and are, therefore, immune to their former coach’s retaliation.

In non-Olympic and non-professional sports such as powerlifting, the level of formal commitment may be a factor that favors the victims. First, the woman does not depend on the sport for scholarship or livelihood. Second, the informality of the institutional setting itself, the number of companies acting as sanctioning bodies (federations), and the competitive classes available make it much easier for the woman to escape a tyrannical sexual abuse relationship like the ones that made the headlines recently. Still, there are predators in any sport because we still have a power asymmetry and, as mentioned before, the imponderable subjective motivators (e.g., psychosis, anti-social personalities, need for sexual dominance, etc.).

The takeaway here is that sexual violence perpetrated by coaches can be dirty but is hardly a secret anymore. If it happens to you or anyone you know, there is a much more hospitable environment to obtain support. Again, self-awareness is the best tool you have to protect yourself against sexual violence in the coach-athlete relationship. Trust is necessary for coaching to happen, but be always aware of the boundaries, always verbalize them, and make sure they are respected.

Is that a guarantee that you will never be a victim of sexual violence? Unfortunately, no.

What if it happens to you? Then you should make use of the resources available to support women in this situation and get help (see below). Some scars cannot be completely healed but they can be managed, and it is possible to live a happy, serene life after abuse.

Coaches as Violence Prevention Advocates

Fortunately, in spite of the potential for predatory activity in the coach-athlete relationship, most of the time it is exactly the opposite. The coach is frequently the only positive figure in a child’s life — a true surrogate parent, like some teachers. In some countries, this is the best children can get (Warren 2012).

There is much more technical and popular literature on the positive role that male coaches played on male athletes' lives. It is unlikely that this reflects anything beyond absence of data and is no reason to suppose male coaches haven’t been surrogate parents and protectors of female athletes as well. This is just less researched and less talked about.

“Coaching Boys Into Men” (CBIM) is an evidence-based adolescent relationship abuse prevention program that trains coaches to deliver violence prevention messages to male athletes. Jaime et al (2015) evaluated the effectiveness of the program and concluded, “Coaches found the program valuable for their athletes and the card series easy to use for delivery of violence prevention messages. Intervention coaches demonstrated significant increases in positive bystander intervention, confidence intervening with athletes, frequency of violence prevention discussions with athletes, and frequency of program discussion with other coaches compared with controls." Of interest to our topic, concerning violence against women, is educating boys to be aware and foster “positive bystander intervention.” Many of the sexual violence scandal cases mentioned above were possible, in part, due to inaction by other members of the community.

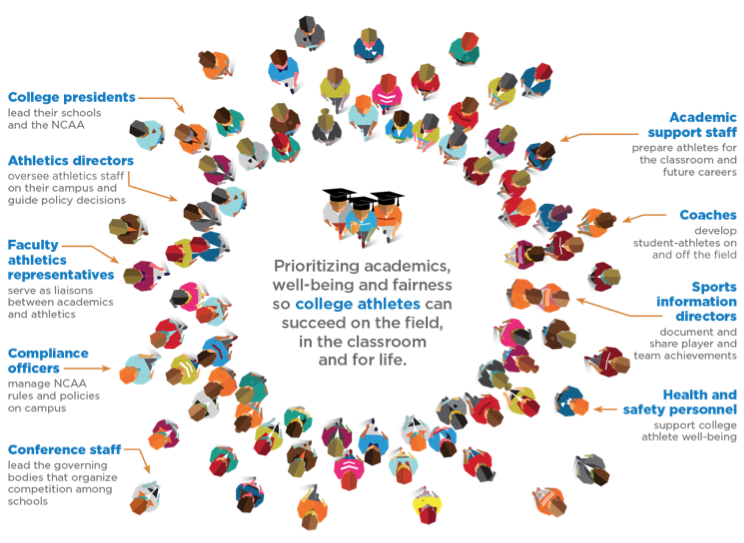

Coaches are frequently the most perceptive members of an athlete’s social network concerning negative emotional experiences, as they directly impact the athlete’s performance and also because of the effective bond between coach and athlete (Raedeke et al 2002). Coaches are also quite aware that action must be taken. For example, consider the firm policy statement by the NCAA, which in great part represents the voice of American Collegiate Coaches.

Fig 3: NCAA members

If collegiate coaches are aware and taking action against sexual violence, there is no reason to suppose non-collegiate and non-professional coaches would not share similar views on the problem. Bringer et al (2002) pointed out, “Some researchers have hypothesized that sexual abuse in sport is not perpetrated by pedophiles alone but also by coaches who have developed a ‘predator’ mentality, and that abusive attitudes may be normative in some sporting environments. As shown in institutional situations, attitudes of non-abusing authority figures can also influence the likelihood of abuse being reported."

In the strength sports, there is anecdotal evidence for this, with coaches, actively not only supporting but also going out of their way to protect women against violence. It is ripe time that these actions become published material. Consider how hard it is to “lead by example” if nobody knows what the example is.

The takeaway here is that male strength coaches would make a great contribution if they shared their experience on this issue. If you are a coach and are afraid to violate your athletes’ privacy, use fictional names and omit too much contextual detail.

Prevention: What Can Be Done and By Whom

This is possibly one of the most important items in this article. If you are undergoing the confusing feelings that you may have done something to prevent the horrible experience of sexual violence, I hope that the statistical information offered here helps ease your pain and also helps you understand that, if you fall into class of the majority of sexual violence cases where the perpetrator is an acquaintance that gained your trust, or you were inebriated or covertly poisoned by this person, there is nothing you could have done. No self-defense class or knowledge of environmental risks could have prevented that. The reason is simple: the perpetrator knows you, knows you trust him, he is determined to rape you, and that is why the sexual violence happened.

Most universities and workplaces offer training programs and literature to help women prevent being victimized. Some of these programs were monitored and actually prevented a large number of assault cases. This is good and means you can do things to protect yourself. First, you can educate yourself on the resources below, whether it ever happened to you or not. Second, you can adopt a more effective attitude in potentially risky situations, read about how predators behave as acquaintances and avoid situations of vulnerability.

Another common advice from the agencies is to watch out for one another. Choose public places for first encounters, avoid being alone with anyone you don’t have complete trust in, and let some close friend or family member know where you are. There are several other guidelines in the resource list compiled here. Please read and contact them if you need clarification. Non-abusive male coaches have a power they haven’t even started to explore in this respect (Bringer et al 2002). They can exert effective preventive action over potential abusers.

The best prevention, however, is effective and mass education of girls and boys, women and men, concerning the nature of sexual violence. Although this article is focused on the male coach to female athlete context, sexual violence happens everywhere, with everyone. We are not talking about a clumsy or bad date, but about violence — intentional aggression using sex as a means to dominate, terrify, hurt, and humiliate somebody else.

With more awareness, communities may improve alertness concerning sexual violence risk and be ready to react, preventing or supporting victims and condemning violent behavior from anyone.

Sexual Violence PTSS and Its Treatments

Most, if not all, victims of sexual violence will tell you that they are scarred for life. Unfortunately, that seems to be true. A study conducted with 25 elite female athletes in Norway (Fasting et al 2002) showed that sexual harassment had a few negative consequences but mostly the women moved on. A “destroyed relationship with the coach” and “a more negative view of men in general” were the most common consequences. Sexual violence up the scale, involving non-consensual sex and sexual assault, has much worse and irreversible consequences. The 2006 CDC report on rape found that many rape victims have serious mental health consequences. The majority loses time from work and a significant part suffers injuries from the incident (Tjaden et al 2006).

The mental health burden of rape is high. The highest risk of PTSD given trauma exposure is rape, with a 19% risk. A comparison with other violent trauma exposure types puts this number in context: combat experience (3.6%), refugee (4.5%), physical abuse in childhood (5%), kidnapped (11%), non-rape sexual assault (10.5%), life-threatening accident other than automobile (4.9%), and unexpected death of a loved one (5.4%) (Kessler et al 2017). Not surprisingly, rape and other forms of sexual assault are significantly correlated with depression, anxiety, and suicide (Mondin et al 2016, Tarzia et al 2017).

One finding is of special importance to the present review: the relationship between rape myth acceptance (RMA) and poor mental health outcomes (depression and alcohol abuse). What Wilson and collaborator’s (2017) study showed, comparing acknowledged to unacknowledged rape survivors, is that among the acknowledged rape survivors, outcomes were worse among the high RMA levels groups, while among the unacknowledged rape survivors, low RMA levels predicted worse outcomes. What does that mean?

First, let us understand what RMA is. Rape myths are “a complex set of cultural beliefs thought to support and perpetuate male sexual violence against women” (Payne et al 1999). Examples are the research results that list the following:

- “She asked for it.”

- “It wasn’t really rape.”

- “He didn’t mean to.”

- “She wanted it.”

- “She lied.”

- “Rape is a trivial event.”

- “Rape is a deviant event.”

The implications of these findings both for mental health prediction and prevention are important. These beliefs are called “myths” because they are not supported by evidence. Therefore, they are wrong. The more these myths are socially deconstructed, the safer the victims will be, whether it is preventing being attacked or dealing with the attack with the lowest possible resulting damage.

Wilson and collaborator’s (2017) findings suggest both that it is important to deconstruct the myths and that acknowledging the violence suffered is important. Denial may protect the victim temporarily, but in the long run, it is damaging.

The Importance of Network Support

The big takeaway of all the evidence accumulated on sexual violence is that although some factors and predictors may never change, others can and will. They can only change, however, through collective action, education, and support networks.

Social isolation is a predictor of many negative health issues, such as depression, the development of other forms of mental suffering, life quality degeneration among the elderly, and vulnerability to violence. In rape, the social response to disclosure can have both positive and negative outcomes, depending on the type of response (Ullman 1999). Institutional response has been unfortunately greatly associated with negative outcomes, leading to secondary victimization (reinforcing self-blame, shaming, etc.).

Social support is, however, difficult to study. Golding and collaborators (2002) found that lack of social support (isolation) is both a predictor of higher sexual assault risk and of poor mental health outcome. This scenario makes it harder to establish a causal connection. In any case, it seems indisputable that reinforcing social networks’ awareness concerning the reality of sexual violence is a determining factor both to prevention and to promoting more effective management of post-trauma outcomes.

The takeaway here is that, in our strength sports community, discussing and educating its members is the best measure we can take now. We must all understand the dynamics of sexual violence in sports, with objectivity and reason, and at the same time listen to the victims’ voices with compassion. Knowledge and reason without compassion are as blind as compassion without knowledge and reason.

List of Resources and More Information

The following resources can provide information and guidance in many situations:

- RAIN National Sexual Assault Hotline 24/7 — Offers support, referral, information, and advice. Provides sections on safety and prevention as well as guidelines for after sexual assault happened.

- Date Rape Drugs – Understand what they are, how they are used, and how to prevent being poisoned.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — Sexual Violence: Prevention Strategies

- Office of Violence Against Women – The US Department of Justice

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center — Of special interest is their list of organizations that offer direct support to victims.

- Women Organized Against Rape — WOAR

- WomensLaw.Org — One of the hardest things in dealing with sexual violence is approaching the legal system. These people can help.

- World Health Organization — Sexual Violence

- US Department of Veterans Affairs — PTSD: National Center for PTSD

- Nicholls State University — Strategies to Help Avoid Sexual Assault and Rape

- Cornell College — Sexual Assault Risk Reduction Strategies

- Planned Parenthood — What should I do if I or someone I know was sexually assaulted?

- International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement — Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport (2016)

- NCAA Board Adopts Sexual Violence Policy — Action also taken on several health and safety initiatives

Most police departments offer special services for rape victims as well, such as:

References

- Anderson, Laura Jane, Asher Flynn, and Jennifer Lucinda Pilgrim. "A global epidemiological perspective on the toxicology of drug-facilitated sexual assault: a systematic review." Journal of forensic and legal medicine (2017).

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

- Beck, A., D. Berzofsky, R. Caspar, and C. Krebs. "Sexual victimization in jails and prisons reported by inmates, 2011–12 update." (2013). https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4654

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Summary: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/datasources.html

- Brackenridge, Celia. "Harassment, sexual abuse, and safety of the female athlete." Clinics in sports medicine 19, no. 2 (2000): 187-198.

- Brake, Deborah L. "Going outside title IX to keep coach-athlete relationships in bounds." Marq. Sports L. Rev. 22 (2011): 395. http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1555&context=sportslaw

- Bringer, Joy D., Celia H. Brackenridge, and Lynne H. Johnston. "Defining appropriateness in coach-athlete sexual relationships: The voice of coaches." Journal of sexual aggression 8, no. 2 (2002): 83-98.

- Fasting, Kari, Celia Brackenridge, and Kristin Walseth. "Consequences of sexual harassment in sport for female athletes." Journal of sexual aggression 8, no. 2 (2002): 37-48.

- Golding, Jacqueline M., Sharon C. Wilsnack, and M. Lynne Cooper. "Sexual assault history and social support: Six general population studies." Journal of Traumatic Stress 15, no. 3 (2002): 187-197.

- Jaime, Maria Catrina D., Heather L. McCauley, Daniel J. Tancredi, Jasmine Nettiksimmons, Michele R. Decker, Jay G. Silverman, Brian O’Connor, Nicholas Stetkevich, and Elizabeth Miller. "Athletic coaches as violence prevention advocates." Journal of interpersonal violence 30, no. 7 (2015): 1090-1111.

- Juhascik, Matthew P., Adam Negrusz, Diana Faugno, Linda Ledray, Pam Greene, Alice Lindner, Barbara Haner, and R. E. Gaensslen. "An Estimate of the Proportion of Drug‐Facilitation of Sexual Assault in Four US Localities." Journal of forensic sciences 52, no. 6 (2007): 1396-1400.

- Kessler, Ronald C., Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Jordi Alonso, Corina Benjet, Evelyn J. Bromet, Graça Cardoso, Louisa Degenhardt et al. "Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys." European journal of psychotraumatology 8, no. sup5 (2017): 1353383. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5632781/?report=printable

- Kilpatrick, Dean G., Heidi S. Resnick, Kenneth J. Ruggiero, Lauren M. Conoscenti, and Jenna McCauley. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. National Criminal Justice Reference Service, 2007. http://www.antoniocasella.eu/archila/Kilpatrick_drug_forcible_rape_2007.pdf

- Malamuth, Neil M. "Predictors of naturalistic sexual aggression." Journal of personality and social psychology 50, no. 5 (1986): 953.

- Modi, Danbaba Enoch, and Ojo Matthias Olufemi Dada. "Myths and Effects of Rape on Male Victicms." Science 1, no. 1 (2015): 1-5.

- Mondin, Thaíse Campos, Taiane de Azevedo Cardoso, Karen Jansen, Caroline Elizabeth Konradt, Rosana Ferrazza Zaltron, Monalisa de Oliveira Behenck, Luciano Dias de Mattos, and Ricardo Azevedo da Silva. "Sexual violence, mood disorders and suicide risk: a population-based study." Ciencia & saude coletiva 21, no. 3 (2016): 853-860.

- Mountjoy, Margo, Celia Brackenridge, Malia Arrington, Cheri Blauwet, Andrea Carska-Sheppard, Kari Fasting, Sandra Kirby et al. "International Olympic Committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport." Br J Sports Med 50, no. 17 (2016): 1019-1029. http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/17/1019.long

- Payne, Diana L., Kimberly A. Lonsway, and Louise F. Fitzgerald. "Rape Myth Acceptance: Exploration of Its Structure and Its Measurement Using theIllinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale." Journal of Research in Personality 33, no. 1 (1999): 27-68.

- Raedeke, Thomas D., Kevin Lunney, and Kirk Venables. "Understanding athletes burnout: Coach perspectives." Journal of Sport Behavior 25, no. 2 (2002): 181.

- Senn, Charlene Y., Misha Eliasziw, Paula C. Barata, Wilfreda E. Thurston, Ian R. Newby-Clark, H. Lorraine Radtke, and Karen L. Hobden. "Efficacy of a sexual assault resistance program for university women." New England journal of medicine 372, no. 24 (2015): 2326-2335. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1411131

- Tarzia, Laura, Sarah Maxwell, Jodie Valpied, Kitty Novy, Rebecca Quake, and Kelsey Hegarty. "Sexual violence associated with poor mental health in women attending Australian general practices." Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 41, no. 5 (2017): 518-523.

- Tjaden, Patricia Godeke, and Nancy Thoennes. "Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey." (2006). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21950

- Tomlinson, Alan, and Ilkay Yorganci. "Male coach/female athlete relations: Gender and power relations in competitive sport." Journal of Sport and Social Issues 21, no. 2 (1997): 134-155.

- Ullman, Sarah E. "Social support and recovery from sexual assault: A review." Aggression and violent behavior 4, no. 3 (1999): 343-358.

- Warren, Angela. "The School-Based Family: Coaches and Teachers as Parental Figures for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Ugandan Schools." (2012). http://jur.byu.edu/?p=366

- Wilson, Laura C., Amie R. Newins, and Susan W. White. "The impact of rape acknowledgment on survivor outcomes: the moderating effects of rape myth acceptance." Journal of clinical psychology (2017).

- World Health Organization (WHO). "World Report on Violence and Health, edited by Étienne G." Krug et al. Geneva: World Health Organization (2002). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42495/1/9241545615_eng.pdf

Editor's Note: Samantha Coleman has worked to communicate with many people who seek to create a hub of resources for helping victims. Through her education, her criminal justice experience, and her own experience as a victim, she has found that there is a profound lack of knowledge and understanding of the experience of victims and the legal rights they possess. While there are many resources available, victims often fail to utilize them due to a lack of knowledge of how to access them, as well as the overwhelming and confusing nature of navigating the justice system. Currently, there is no centralized database for victims to find these legal resources. Samantha's hope is to provide access to as much of that information as possible.

Justice, Coping, and Recovery for Victims of Sexual Violence

In today’s vast reaching social media outlets, news and awareness of sexual violence travels faster than ever before. In recent months, the #metoo movement has demonstrated the commonality of sexual violence in all walks of life. Additionally, this movement has revealed sexual violence to be a social norm across many different cultures. Advocates with good intentions turn to social media to balance this common injustice, but this action rarely provides useful resources for victims of sexual violence.

As a victim of sexual violence and a woman who has experience in the criminal justice system, I often find that social justice in these cases provide little to no resources for victims other than a small measure of vindication and public support. Do not be mistaken, public awareness of known sexual predators is vital toward helping victims. However, groundless accusations lessen the credibility and effectiveness of the efforts toward combating and providing useable resources for all victims.

My first experience with sexual violence happened before social media. I didn’t have a social platform to spread my experience and warn others. Due to my previous experience with the criminal justice system related to domestic violence, I became convinced justice did not exist for me. I chose to deal with my own experience internally, and through years of self-inflicted hardships as a result of that experience, I eventually educated myself on how to help others through the proper channels, as well as arm myself with knowledge.

Many victims feel the justice system fails to provide help. I can understand this because, in my earlier experiences, I felt the same. The truth is that law enforcement officers have to follow the evidence and make decisions based on what can be proven. In our great country, we have the Fifth Amendment, which says that every citizen is afforded the right to due process. Anyone who has been falsely accused of a crime can attest to the importance of the Fifth Amendment. Without this right, our society falls prey to witch-hunts, and as history will demonstrate, accusation without evidence is damaging to everyone’s rights and freedoms, including those who are victims of these vicious crimes.

The stress associated with sexual violence victimization can cloud our decision — not to mention, many victims, like most people in our society, have no idea how to navigate the red tape of the criminal justice system. The goal in any sexual assault case is to bring justice to aggressors and to ensure victim protection, as well as prevent these aggressors from harming others. However, our first priority should be to provide resources to victims that will aid in recovery and justice.

There are several important things to understand about instances of sexual violence and how to address the issue:

1. Many victims of sexual violence experience it with close friends, family, or people they trust. If you are able, please report these crimes to the police when they happen. You have the right to request a female officer and female doctor to take your report and conduct an examination respectively. You can go to any local emergency room and request an examination. The number one reason rapists never face the consequences of their crime is that these crimes are not reported.

2. Victims are NOT obligated to report these crimes. However, resorting to social media to “out” these aggressors, thus bypassing the legal system, diminishes the credibility of all victims and creates more victims in the process. The lack of justice due to none reporting in these cases leads to the “social crucifixion” of those close to the victim and aggressor rather than the aggressor directly.

3. If you are able and do report these crimes, most jurisdictions provide victims rights advocates who will help guide you through the legal system. In areas that do not have local advocate programs, national and non-profit organizations will help provide you with an advocate. Victims cannot be expected to know how to navigate the legal system and these programs can bridge that gap. These advocate programs can help provide victims with legal counsel in addition to local, state, or national programs designed to help victims seek justice, but more importantly, recover from these incidents.

4. Be informed! All resources afforded to victims can be accessed through internet searches, local hospitals, police departments, churches, etc. Reach out to organizations with an obligation toward public service. These organizations, as well as state facilities, have a legal obligation to provide resources to victims without judgment or agenda. These are resources provided for you — do not be afraid to ask about them.

Victims must remember that the only obligation they have is to self-recovery. Some victims seek legal justice while some find solace in quiet recovery. There is no right or wrong way to overcome sexual violence. Be informed of your options and choose the best option for you.

Samantha Coleman has a degree in criminal justice administration with a minor in biology. She has four years of law enforcement experience working with the public to help victims and families alike. Samantha is also an elite powerlifter and a professional strongwoman competitor, holding multiple world records in both sports. She was recently inducted into the 2018 Guinness Book of World Records for her athletic feats of strength.