“Everyone ends up at the doctor’s office or the hospital, some time or other. In great part, you decide why and how.” — Paulo Muzy, MD, circa 2009

Paulo (or Dr. Muzy) is a friend and was my physician for years when I lived in Brazil. He is also a speaker. In the lecture from which I took the above quote he wanted to make a point concerning preventive medicine: statistically, the sedentary individual with poor health habits will need medical attention for very different reasons from active individuals with healthy habits. Statistically, too, healthy athletes manage a much lighter injury burden compared to their unhealthy counterparts so that their detraining and retraining periods are shorter. They are still, statistically, unavoidable.

Introduction

Once in a blue moon, I publish something personal here. This is it for the year: my cycle of detraining and retraining. It strongly relies on information and concepts from my previous article.

Technically, I am not an athlete since 2017, when I did my last meet. Couldn’t I consider this a long detraining period? That’s my point here: the frequency of my detraining/retraining episodes per year has steadily increased and the periods of both detraining and retraining have expanded. Finally, they reached a stage when there is no point in competing until… Until what?

One important issue is that while detraining is mostly unpredictable, retraining can be predictable to a certain degree. The most important thing in predicting (and planning or programming) a retraining period is setting a goal: what do I want to reach? You know we can get under a bar at the platform while not rehabilitated. You also know that frequently, complete recovery/rehabilitation is impossible: you live with a chronic injury and still get under the bar at the platform.

The parameters for deciding the retraining period are in great part subjective.

The story I’m going to tell is at the same time about being prepared or not for the inevitable detraining periods after injuries, about getting old as an athlete and about faith and transcendence. It meant accepting a permanent cycle of detraining and retraining. This was only possible because of a paradoxical combination of scientific pragmatism and passionate faith.

The Young Fighter: Faith and Love

Around age 10 and 11, I was in an athletic talent screening program in a reputable sports center in Brazil, the “Clube Pinheiros”. Children were grouped by age and each semester we would experience a certain number of sports, three or four times a week. At the end of each stage, the coaches would select the children that scored high in their talent screening system. I was selected by the track and field, gymnastics and fencing coaches but I had already fallen in love with fencing.

During the four years in which I practiced fencing, I had two injuries and one illness (hepatitis). Hepatitis came first and I don’t remember minding the detraining period. I started missing fencing when I was close to being cleared by the doctor and I don’t recall any retraining proper.

Then there was a minor adductor tear during a lunge. I don’t even remember detraining at all: I suppose (but just suppose) Master had me not doing lunges for a while.

At one time, however, close to the Nationals for my age class, I was faced with a serious detraining process. After some time fighting, my right hand’s thumb muscles started spasming until the hand eventually opened and dropped the weapon (foil). Everyone was concerned. The first physician we saw had some X-rays done and concluded there was a “strange mass” at the thenar region, possibly a tumor, and that I wouldn’t fight anymore. Big mistake: Master was furious, they quickly found another doctor who said it was impossible to diagnose, gave me a cortisone shot and a couple of weeks of rest until the mysterious mass shrank.

I don’t remember my immediate reaction. I think I was very scared. I think my mother took me right back to the club from the clinic. Master immediately devised a plan: I would become a southpaw. He was ambidextrous and he decided he would make one out of me. I was a very well-educated teenager and my parents are scientists. It has been known for a while that re-learning skills and changing one’s congenital dominant side are extremely rare and require unreal effort and motivation (Deora et al 2019). A part of me, however, just believed that no matter how impossible it seemed, if Master decided it would happen, and I’d still make him proud by winning the Nationals with the left hand, it would. Master was my second father and I loved him almost as my own. There's more: by not being my real father, my devotion was unambivalent. He succeeded in the unimaginable: he gave me the ability to have faith. I’m a second-generation atheist. I didn’t and don’t know what religious faith feels like. I think that’s the closest I’ve come to it: Master said it would happen and that means it would.

My first experience with detraining gave me a new skill: faith. It also took to the extreme my inherent grit, mental toughness, and resilience. I would go to school and painfully write pages and pages with my left hand. It looked horrible but I got better each day. I did everything with my left hand. I practiced kinesthetic awareness with small rubber balls that I’d throw and catch, hours and hours every day. Fencing with the left hand, every day, Sundays included.

My right hand eventually recovered from the inflammation but there was a sequelae: muscle weakness. The spasming and loss of control would remain with me for the rest of my days as a fencer. The Federation’s president and Master came up with a device that attached the foil’s handle to my wrist, like a bracelet. In theory, it would be detrimental to my precision but that was what they decided and that’s what I did.

I have no recollection of the retraining period. One day we just dropped the southpaw project and everything was back to normal except for the bracelet.

I won the Nationals. I made Master happy.

Faith, that controversial and mysterious property of the self. It is not just a belief in something despite the absence of evidence. It is a connection to something transcendent. The true martial artist fights himself at every match. He is on a journey into the unknown improvement of the soul. When he is young, still a disciple, his reference is his Master. In fencing, when your opponent puts on his mask, wearing the same white tunic as yours, he lends his body to this other you.

A young martial artist doesn’t know his path yet: he follows his Master. He obeys. There is serenity in this level of trust. There is happiness. Nothing else matters. The self dissolves, limits fade away and the impossible becomes tangible.

I never left fencing. In 1978, I was forced to leave everything that mattered to me by the political circumstances in Brazil and by uncaring adults who made very bad choices for me. Maybe because I never left it, because my days as a fencer and Master’s teachings remained hidden in a very protected inner part of me, detraining and retraining were never a big deal.

What’s in That Envelope?

I overcame a bunch of supposedly impossible obstacles in different aspects of life while they were still transcendent. Unraveling the mysteries of an incurable disease that kills only the very poor, creating the right circumstances for peripheral countries to catch up with the central ones in science and technology and protecting the Amazon from biopiracy. At one point or another, I got too tired of failing and lost faith.

Powerlifting was not different: it started for me at a slum in São Paulo where 80 thousand people, mostly discriminated migrants from the Northeastern states of the country, lived in poverty and vulnerable to violence. In the middle of the slum, there was a powerlifting gym. It was there that I found meaning after surviving a suicide attempt. Eventually, some petty federation war destroyed the social project but I was hooked: I had already built faith in the power of powerlifting to promote social inclusion, to be a foundation for health and for bringing people back to life.

I was 43 years old. Like every athlete, I handled detraining and retraining as a result of injuries and illness.

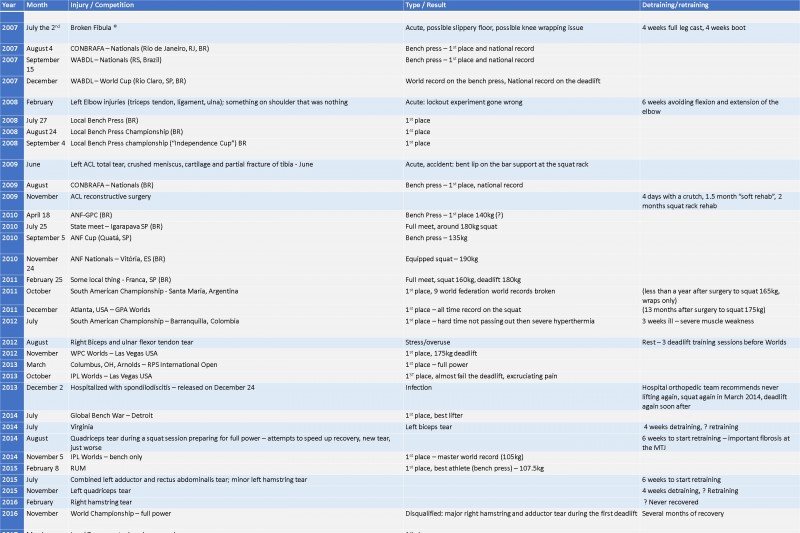

Below are the markers of my detraining and retraining periods. I left out many events (both injuries and competitions), but I tried to fit into the same table the significant ones for the purpose of this article. You will see a couple of World Championships and irrelevant local ones, a biceps tear and a potentially lethal spinal infection. The point is that there is a pattern: during the first years (from 2006 to 2012), all injuries were acute and a result of accidents. From then on, they look like overuse and recurrent injuries. I was always training and competing through, across or around one or more injuries. From 2015 to 2017 I was full-time injured and full-time training through injuries. The early “faith-skill” I learned from Master was my weapon to rip apart limits (records) and ignore pain.

The first injury, a broken right fibula in 207, was the one I handled the detraining and retraining in the most immature manner: faith turned into defiance. Many “national” championships were pretty much backyard meets in Brazil and there was no need for me to make interstate trips with a broken leg to participate.

Two weeks before the only one with a little more relevance, a bar loaded with 110kg (242lbs) was dropped on my face. I had just locked out the bench press while breaking in a Titan F6 bench shirt. The untrained spotters didn’t catch it. To this day, we have no idea why I didn’t die or why at least I didn’t end up with a crushed skull and broken teeth. Only the nose was broken, I had a hallucinatory concussion that made me laugh non-stop, got a throat infection because my sinuses were clogged with blood and broke a world record.

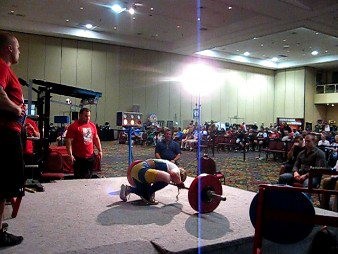

A national championship in Brazil – Rio de Janeiro, RJ – August 4, 2007

A world cup in Brazil – Rio Claro, SP – December 2007

A world cup in Brazil – Rio Claro, SP – December 2007

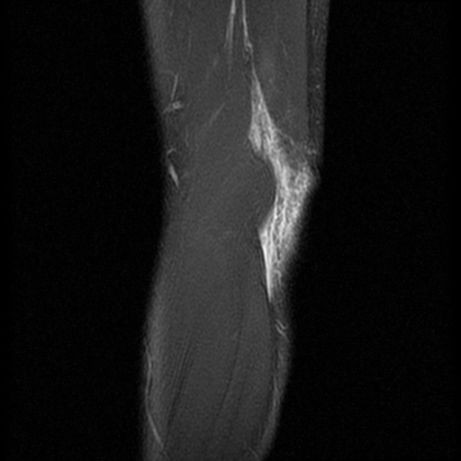

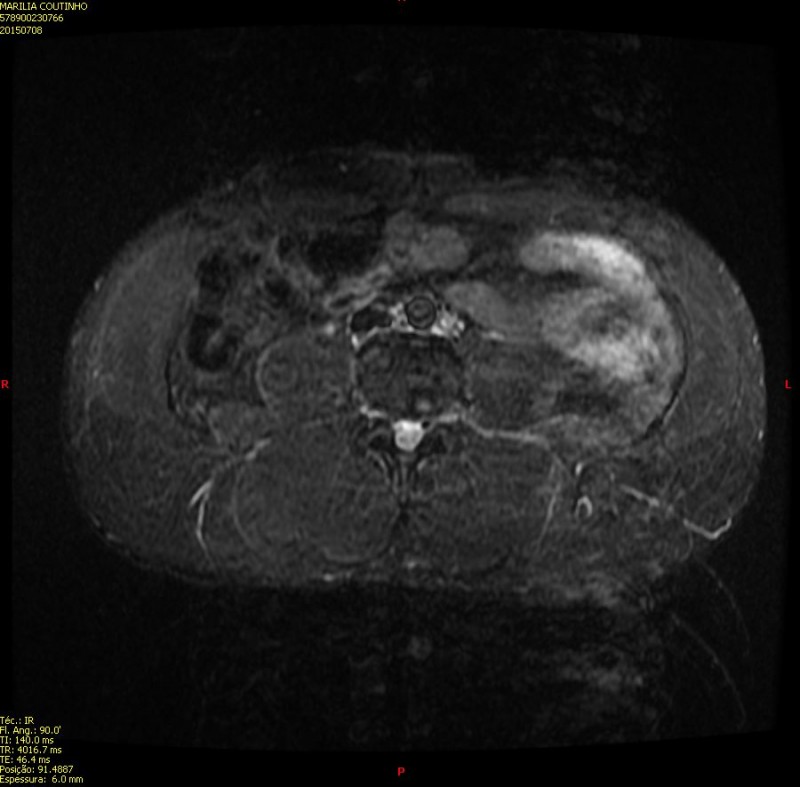

During the second injury (left elbow tendon, ligament and bone injury) there was a moment of "faith-testing". The day after a lockout accident my elbow felt sore. I called my physician, told him I was leaving to go to the gym and whether I should be concerned. He told me to be at the clinic in one hour. I promised to not bench until the MRIs were done and here is what he saw:

Elbow – 2008

Elbow – 2008

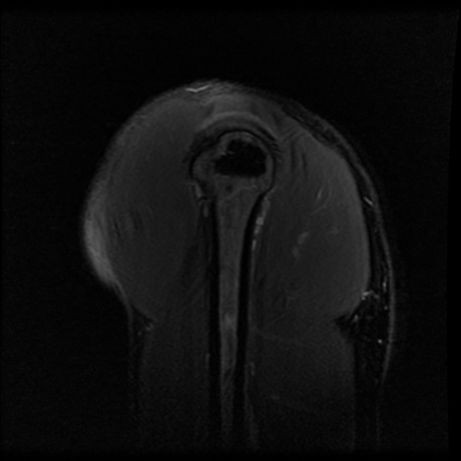

Shoulder – 2008

At the head of the humerus, there was a strange mass that he didn’t recognize. It could be many things including avascular necrosis, in which case there could be others, in other bones, and it could be related to bone cancer. Scintigraphy was needed. As I was sitting at the lab’s waiting room, I realized I was surrounded by cancer patients. Some part of me felt ashamed for not caring whether I was going to die of cancer or not. Another felt annoyed that people close to me were upset. I went to pick up the results alone. Few people knew, but I had received a prognosis that I wouldn’t live much longer than 2010. I was already operating on a tight schedule. As I opened the envelope, I started laughing.

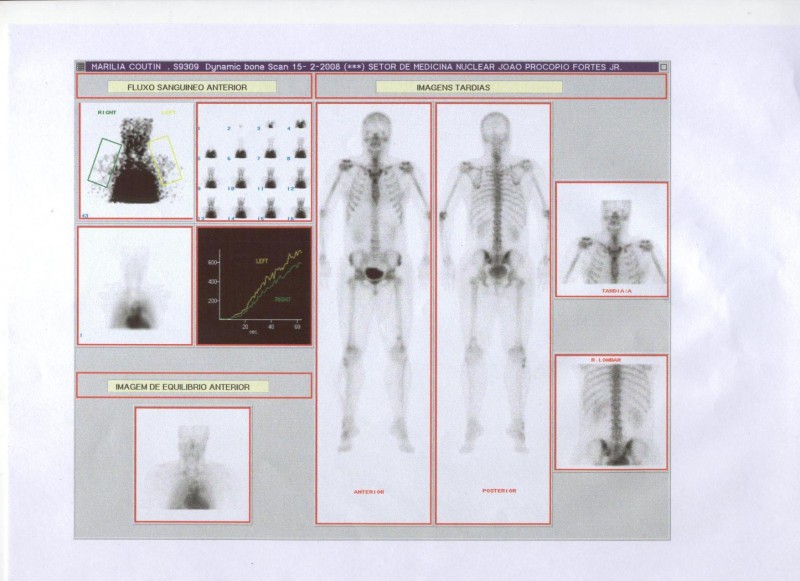

Scintigraphy – February 2008

The black areas in the skeleton are called “hot spots”. They are the opposite of the “cold spots”, which indicate avascular necroses, areas where there is little blood flow and cell metabolism. The hot spots indicate areas of intense osteoblastic activity (making new bone): shoulder, elbows, the middle of the spine, knees and the upper part of the fibula. It took a special session of 12 participants of the National Orthopedics Congress to figure that one out: “the patient is chronically subjected to mechanical overload”.

Some local meet in Brazil – Leme, SP – August 24, 2008

On June 2009, as I was preparing for a World Championship that would take place in Ireland, a defective squat rack caused another dramatic accident: as I was racking 120kg (264lbs), the left end of the bar slipped and twisted my body over the left foot crushing menisci, cartilage, bone and snapping the ACL. I tried to train with the ruptured ACL and when, after a few months, I squatted (full gear) 180kg and felt unstable, I gave up, to my physicians’ relief: we scheduled the surgery for November. The list of videos below contains both post-injury rehab and post-surgery rehab exercises.

ACL injury and reconstruction surgery rehab - 2009-10 - YouTube

The list contains videos of the attempt to recovery without surgery after the accident (June 2009) and the post-surgery rehabilitation exercises.

The list contains videos of the attempt to recovery without surgery after the accident (June 2009) and the post-surgery rehabilitation exercises.

After that, I’m sure I had minor injuries but the record shows I was on my way to increased performance. It was almost a linear path until December 2011, when I broke a squat all-time record.

Some national championship in Brazil – Quata, SP – September 7, 2010

Another national championship – Vitoria, ES, Brazil – November 2010

Some national championship in Brazil – Franca, SP – February 2011

A World Championship – Atlanta, GA, USA – December 2011

A World Championship – Las Vegas, NV, USA – November 2012

The second phase of my powerlifting athletic life began in 2012 with a severe heat illness in Colombia. I continued to compete internationally but the following year I was hospitalized with a serious spinal infection that almost killed me. The hospital orthopedists told me I’d never lift again and one of them almost lost his license because he said that. Faith didn’t make me reckless. It made me angry, dangerous and destructive.

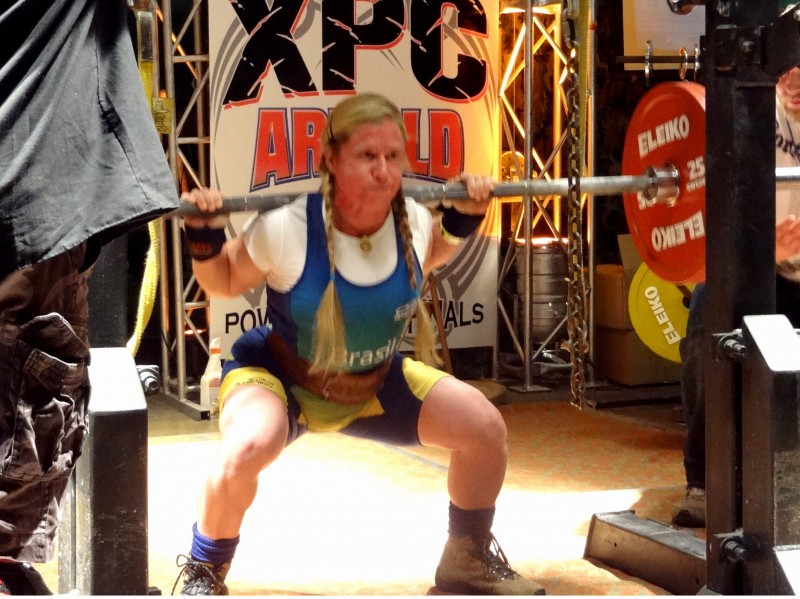

An International Championship – March 2013 – Columbus, OH, USA

After that, I had three decent bench-only International competitions until 2015. In all of them, I competed injured. Then all hell broke loose: I had simultaneous adductor and rectus abdominis longitudinal tears, quadriceps and hamstring tears.

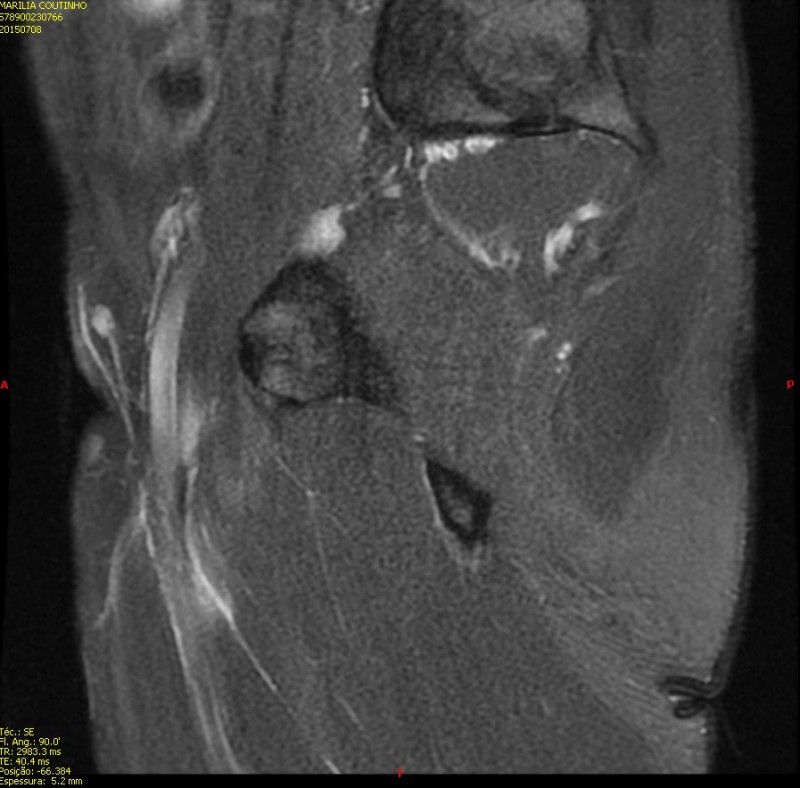

Rectus abdominis longitudinal tear (left side), partial avulsion from its origin at the pubic crest of the pelvic bone – July 215

Longitudinal left adductor longus tear with partial avulsion from its origin at the inferior rami of the pubis – July 2015

As incompletely recovered injuries piled one over the other, I still tried to compete at a World Championship in 2016. A 14-hour flight with multiple connections (I was an international judge, so the federation booked my flight), injuries, hemorrhoids, dehydration did it: I had a major hamstring and adductor tear during the first deadlift while I was a good 50kg (110lbs) ahead of the 2nd placed lifter. That was still not enough to shake my faith.

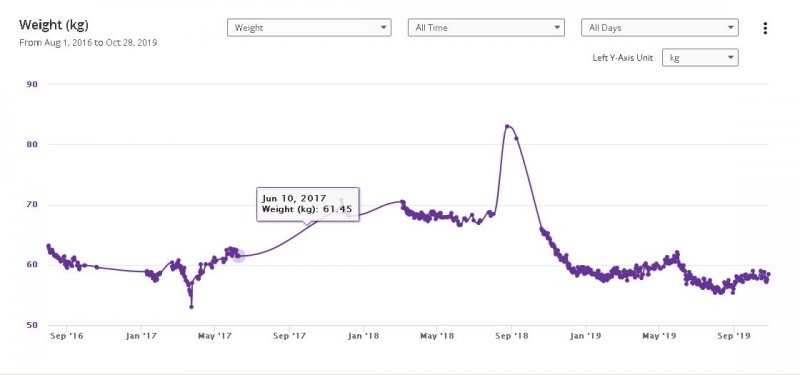

On June the 3rd, 2017, though, I was attacked by what would be to me a random person inside a strength gym, while supervising my athletes. The attack evolved into a snowball of orthopedic, neurological and finally endocrine disorders, many of them irreversible.

Effect of hypothyroidism on rapid weight gain

But there was a stronger reason why I never fully recovered, or never recovered to the point of competing again: I lost my faith.

Concluding Remarks

For me, detraining was a period in which I handled images and test results that nobody could make a proper sense of except catastrophic ones. I revived Master’s southpaw plan and spent every single day sweating my way into remaking myself. Retraining was always a piece of cake: the part of pushing through the task of believing the unbelievable, that was already done.

Will this ever happen again in powerlifting or any other sport for me? Maybe. Because, you see, my faith never had anything to do with powerlifting as a sport. That was what I failed to understand and what made me invest in fake projects, fake people and false ideas. Breaking my own physical limits and sharing strength with those disempowered had nothing to do with federations, medals, trophies or people with limited character.

I am just out of mandatory Oklahoma Summer detraining, when I always get sick. I’m moving, though and I have a very well-equipped home gym. Maybe I won’t be interrupted during every retraining period by an illness or injury-related detraining one. Maybe I’ll find meaning in getting under the bar at the platform again. Maybe I will place faith there again, as I place in strength.

Really enjoyed reading this article. Wisdom from experience is a valuable tool.