Think of all of the potential gym-related injuries that you could have. Where would you place a lower back injury? Top three? Number one? And think of how many fellow lifters you know who either has suffered a lower back injury in the past or are currently dealing with one now. Maybe you even have one yourself.

Out of all of the possible injuries you could have, the lower back may very well affect the largest amount of your training: squatting, deadlifting, overhead pressing, or even a curl. There is a large number of movements that many lifters will simply give up on because they can’t perform them pain-free. I see it often in my clients. I work mostly with the busy professional “desk jockey” population where things like doing the laundry have become high-intensity sports that have damaged more than one back. I’ve even spent the last seven years working around disc herniations as a result of a rear-end collision, so I’ve been on both sides of the fence with this one.

RECENT: Bodybuilding Exercises for Powerlifters — Adductor Work for Added Gains

Continuing to keep up with serious training can be extremely difficult, particularly when it comes to training the lower body. Squatting and deadlifting, especially if an injury is still fresh, tend to be taken completely out of the rotation, leaving most injured lifters on a steady diet of leg extensions, leg curls, and maybe a leg press if they have the flexibility to get a decent range of motion without their lower back going into a rounded state at the bottom. But it’s still not quite the same.

In our gym, we don’t even have machines to do those movements. We’re equipped with eight half racks and benches and four glute-ham raise benches. So if we want to come up with lower back-friendly training sessions for our desk jockey client base, we have to learn to get creative. And we have. One of my go-to methods for getting around lower back injury or overuse is unilateral training.

Unilateral Training: A Vastly Underrated Training Tool

While you do admittedly see more strength athletes using movements like lunges in their programming than you used to, they still are very seldom given a high-profile position in the workout and are usually limited to a couple of high-rep “burnout” sets at the end of a leg day. But when it comes to limiting stress on the erectors, single-leg training can be a great tool for creating hypertrophy in the legs and glutes.

Think of it this way: because training on one leg automatically requires a significant reduction in the amount of weight I can put on that leg, the stress on the lower back has to go down substantially. If I have a client who can back squat 300 pounds, I might give them 50 or 55-pound dumbbells to do a split squat (which is basically just a lunge without a step forward or backward). So instead of 300 pounds that I have to support, I have 100-110 pounds. And that’s to say nothing of the fact that there isn’t any spinal loading, which can make it even more favorable.

Types of Single-Leg Training

In the realm of replacing the compound nature of squats and deadlifts, there are three different unilateral lifts that would make sense: the split squat (or lunge), the single-leg deadlift, and the step-up. Depending on what you’re trying to accomplish, you can play around with the structure and placement of each during your training session or training cycle.

Split Squats and Lunges

The difference between a lunge and a split squat is the step — that’s about it. So if your goal is to use the most loading potential, stepping back and forth with heavy dumbbells or a bar on your back isn’t going to be the best choice. But if you want to get more volume or even reap some conditioning benefit, using lunging variations have their place.

Options: Split squat, front-foot elevated split squat, rear-foot elevated split squat (Bulgarian split squat), forward lunge, reverse lunge, and walking lunges.

Single-Leg Deadlifts

The options here fall into the categories of barbell versus dumbbell and supported versus unsupported. For pure hypertrophy, I’m partial to keeping the rear leg supported on a bench or box and using dumbbells over barbells purely from a practical setup standpoint. Plus, that particular setup lends itself well to continuous tension on the hamstrings and glutes and keeps balance from becoming the most limiting factor.

Options: Single-leg deadlifts with a barbell, dumbbells, or kettlebell, and single-leg Romanian deadlifts with the same implements.

Step-Ups

For most people in the strength world, the perception is that step-ups are only useful if you’re wearing a leotard and holding pink dumbbells. But if they’re executed correctly, they can be a great addition to a hypertrophy program. There are several things to look out for to ensure that they’re done correctly:

- Stay close to the step or bench that you’re stepping to. A step-up is an up and down movement, not a forward and back movement. You shouldn’t need to gather any forward momentum to finish your rep.

- Keep the back leg out of it. If you’re using a bench, often just staying close enough that your back foot is under the bench will limit you from kicking off, as your leg will simply hit the bench and you won’t get any momentum. But to be safe, try to deliberately lock the back knee, and you can even lift your rear leg’s toes off the floor to eliminate momentum at both the knee and ankle

- Keep your butt under your shoulders. Don’t sit back with your hips, or you’re emulating a squat. A step-up is not a squat. No back and forth movement, just up and down.

- Don’t swing your dumbbells so hard that you’re being propelled into the air by their momentum. Keep the weights by your sides or use a barbell to load the movement.

- Control the descent. You don’t have to go in slow motion, but it’s possible to take two to three seconds to lower yourself down without giving in to gravity completely.

Options: Barbell step-up, dumbbell step-up, Russian step-up, side step-up, crossover step-up, Poliquin step-up, Petersen step-up, and the lunging step-up.

The “Potential for Pain” with Unilateral Training

One of my favorite techniques for single-leg training in hypertrophy programs is to use supersets, tri-sets, and giant sets. When done correctly, you’re doing two to four movements all on one leg, and only then can you switch legs and repeat the sequence. The amount of lactic acid buildup that you can get when these are done correctly is unreal, and one of the biggest benefits is the added layer of glute development that you can get from it. Many of my clients find it much easier to feel their glutes on split squats and lunges compared to a traditional squat, and some are able to return to squatting and deadlifting once their glutes get up to the point where the lower back has to take less of the burden.

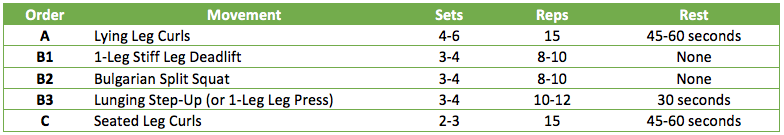

Here is one of my personal favorite "pump day” style workouts using this technique. Training under John Meadows and Cris Edmonds during my last contest prep, when we wanted more volume for my legs I would do the base/heavy day on Monday, and rotate this in every other Friday (the other pump day being more traditional straight sets).

A. Lying Leg Curls. The main emphasis on the tri-set is posterior chain work, and I found that using these to pre-exhaust worked extremely well.

B1. Single-Leg Stiff-Leg Deadlift. Have your back leg supported on a bench, far enough from the bench that you can’t put much weight on the back leg. I like doing these with a single dumbbell instead of two and holding it opposite of my working leg. Hinge back for a stretch, but when you stand up, you only want to return so your shoulders and hips form a straight line with your back leg, not your front leg. This prevents hyperextension and keeps constant tension on the hamstrings and glutes.

B2. Bulgarian Split Squat. You should be able to drop right into these without much readjusting of your body position. Keeping a slight forward tilt at your torso will amp up the glute work, especially since they’re already exhausted. If you want more quad work, you’ll want to put these first in the rotation.

B3. Lunging Step-Up. They’re literally half-lunge, half-step-up. The added hip and knee flexion out of the bottom range once again will ramp up the glute involvement, and by this point, you will probably need little to no weight. I would go with maybe 20-30% of what you used for the first two movements as a decent starting point, but I’ve seen many guys struggle with just their own body weight without getting sloppy.

Now, in all fairness, when I have regular access to a leg press, I will routinely drop in a one-leg leg press in replacement of the lunging step-up, especially if I want more quad work. 10-12 reps with my heel low on the platform works perfectly.

The part that destroys many a soul is that, after all, three movements done consecutively on one leg, you’re only going to rest about 30 seconds before tackling the other leg. Because the loads are lower, it’s pretty rare that your heart rate is high enough to warrant more rest than that. And your working leg now gets a bit of rest while you work the other leg, so it’ll still get a good two minutes or so of rest before you repeat.

Start with three rounds. Anything more than four is completely unnecessary, and if you can do it, you’re probably not working hard enough.

C. Seated Leg Curls. Because it’s pump day. Why not?

Off-Season Back Training: Two Sessions Per Week and More Adjustments

Zach is the co-owner and head strength coach of All Strength Training, a personal training center specializing in busy professionals located in Chicago, IL. He is also a competitive physique athlete, earning his WBFF fitness model pro card in 2016, and is training for his pro debut in 2017. For more information visit www.allstrengthtraining.com.

2 Comments