DISCLAIMER: Suicide rates are lower among athletes when compared to the general population according to most studies (Joiner 2006). Most suicides in the highest risk group (young adults) are associated with untreated or unsuccessfully treated mental illness (McLean et al 2008). Mental health statistics about involvement with sports, especially among the young, suggests that the latter is protective of athletes’ mental health (Tamori and Zalar 2000, Taliaferro et al 2008). The reason suicide is the fourth article in this series is to explore the contrasts between presence and absence of the conditions previously discussed related to motivation.

We begin with a story. She drove alone to a beach house far from where she lived. She had been strength training before with no specific athletic objective, but it had been weeks since she had done anything at the weight room. Medication made her feel like a vegetable, so she was off medication for a while already. She had left her previous occupation, too disappointed with the institutional system. Meaninglessness was a big black hole inside her mind, sucking everything into a vortex.

At the beach house, she slept a lot in the beginning and then not at all. She ran miles every day on the shore, nobody to see or talk to. She stopped eating. On the fourth day, she decided to visit an improvised weight room she knew about. In the middle of the way, she stopped at a store and bought razors. She turned into a secluded dirt road where nobody would see the car. There, with her right hand, she slashed her throat. It didn’t even hurt. For an unknown lapse of time she just stood there until she felt everything was wet. She turned the rear mirror to her and saw the open wound. “Oh… I’m dead…”, she said to herself. “So that’s how it ends…” And she was disappointed. Because right after slashing her throat her thoughts became much more linear. “Too late,” she thought. It was then that she noticed a man walking down the road.

“Hey, mister, could you help me? I was trying to get rid of my bikini and accidentally hurt myself. Is there a hospital around here?”

The man told her to move to the passenger seat and took the wheel. He drove as fast as he could. She was totally calm.

PART 1: Why Do You Lift — Meaning, Identity, Hope and Passion

At the very simple clinic there were no resources to do much more than what they did, which was to stitch her up as best as they could.

“Look, we’re far from everything. We don’t have a surgery room here and we couldn’t identify much of what we saw: there was too much blood. Part of the jugular was cut, nerves, we don’t know what else. If the cut leaks, you will go into a coma in the next half hour. If that happens, there is nothing we can do: you will die. So just stay here and we’ll see what happens. Good luck.”

During the weirdest half hour of her life, she made an inventory of what happened until that moment. She had “lost faith” and gained faith again so many times that she was used to this. She thought this was the final one. However, during that half hour, she began to make plans for the eventuality of her survival. She figured that what brought her to that desert dirt road was lack of training. Maybe that was the experiment she never read about, for obvious reasons (it didn’t exist). Dopamine? Testosterone? What? Something was missing that made her mind, usually clear, so foggy. If she survived, she would find that out. How? No ethical committee would ever approve of an experiment. No, it would be a case study. She would document all the relevant variables related to suicide from the moment she got up to the moment she went to bed: appetite, any cravings, food habits, hydration, libido…variations in some indicator in her blood work. Which ones? She would figure out. How would she make sure she concluded her case study? She had to take measures to defend herself against the urge to die. She didn’t know it, but she had just done that: she created goals, a time frame, plans A, B, and C and she recovered a drive to accomplish something.

She drove back to the city. Three long hours on desert roads until she arrived home at 3 AM. The following days she had to be examined by more doctors who had hostile mixed feelings.

She met the psychiatrist that used to see her before. He said that, for the first time, the department had “a pure severe case” in their hands, meaning the untreated mental condition. That it was interesting, but unfortunately, if she refused treatment, she would die in the following months.

“You know the progression and degeneration. Episodes will happen with higher and higher frequency, stronger and stronger, and it is well established that there is no way to stop a smart suicidal person from doing it. If you are very lucky, you have five years at the most.”

“I thank you,” she said, “but I had a lot of time to make up my mind. I don’t have much longer to live. So I will live as intensely as possible. I have a lot to write and do, I have a legacy to leave and there is a life I never had to live in a short time. I’m in a hurry. I can’t have drugs slowing me down.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “You will be a great loss.”

The story you just read is written in the third person, but that woman is me. The unsuccessful suicide happened on the 4th of July of 2005. My deadline (pun intended) was July the 4th, 2010.

I began my experiment that same week. The doctors had told me I could not train for two months. I knew that if I followed that advice I’d be dead. They also said that the numbness on the left side of my face might or might not subside. It never did. The numbness and the itching at the scar, those I carry to this day, may be to remind me that this is not over. It will never be.

About six to eight months after that 4th of July I discovered powerlifting. Around it, intrinsic and extrinsic motivators (see part one), a path to transcendence, passions of all types (see part two), goals with strict time frames and hope (part three).

Why did I tell this story, apart from being a textbook suicide case that, having been unsuccessful, gives us some insight into the subject? Because basically all the items that I introduced you to on part one, two, and three are evidenced here through their absence and then, again, through their recovery.

Nature and Nurture — Let’s Get Done With This One

Before highlighting the issues that pertain to our motivation discussion, it is important to clarify that like so many other phenomena, suicide is a product of physiologic, psychologic and social determinants.

The relationship between each risk factor and the act of an individual suicide itself is not sufficiently predictive, though. Suicide has been studied in relation to many measurable variables, such as age, sex, previous suicide or self-harm attempt, a mental illness diagnosis, unemployment, poverty, religion, marital status, etc.

PART 2: Why Do You Lift — Defining Passion

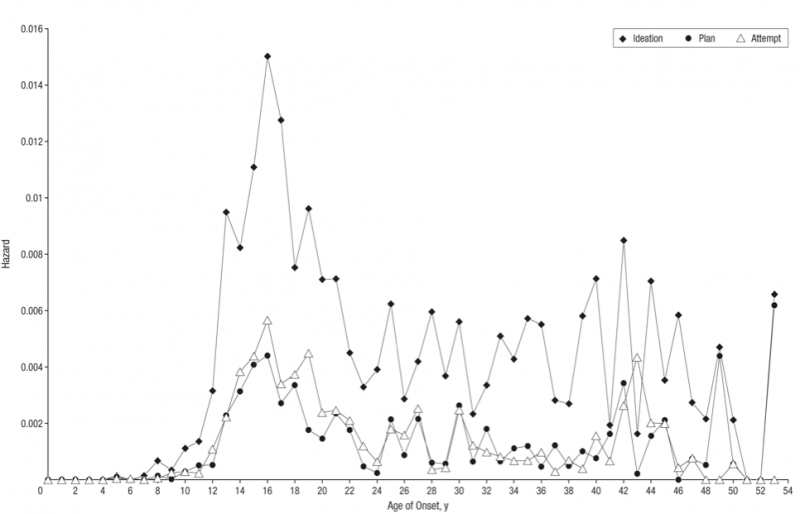

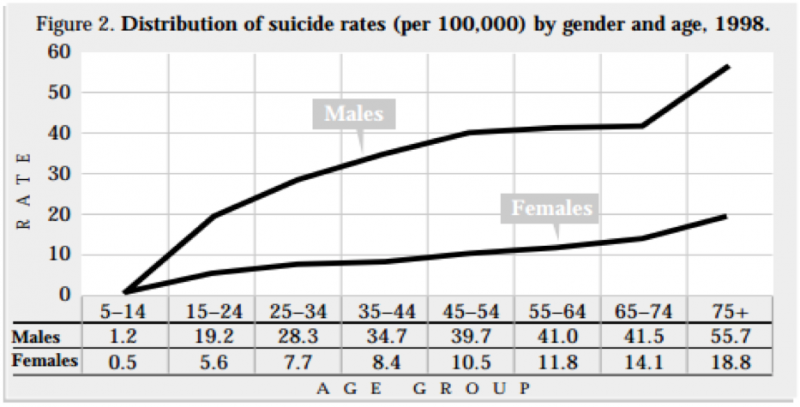

Most epidemiological studies show there are three critical age groups for suicide risk: from 15-20, from 35-45 and another peak among the elderly:

From Kessler at al 1990.

From Bertolote and Fleischmann 2015.

For all age groups, sexes and different cultural settings, a history of mental illness has been established as a risk factor for completed suicide (McLean 2008). In a review of 13 studies from seven countries, Fleischmann et al (2005) found that the majority of cases (88.6%) had a diagnosis of at least one mental disorder. Mood disorders were most frequent (42.1%), followed by substance-related disorders (40.8%) and disruptive behavior disorders (20.8%). The analysis included 894 suicide completers with an age range of 10-30 years.

The idea that all suicides must be a result of mental illness has been increasingly challenged. The term “predicament suicide” has been coined to describe the suicide which occurs when the individual without mental disorder is under unacceptable circumstances from which he cannot find an acceptable alternative means of escape (Pridmore 2009, Pridmore et al 2009).

Ironically, suicide first became the focus of scientific study as a social phenomenon. Emile Durkheim, in his pioneering work in the social sciences “Suicide: a study in sociology” (1897), carried out the first systematic study about suicide. Some of his findings are constant through the decades (or centuries): higher rates of suicide among men than among women; higher rates among soldiers than among civilians; higher rates of suicide among people without children, etc.

Durkheim, however, proposed a model through which the social environment shapes the type of suicide executed at the individual level, and that is important to our discussion on motivation. The four types of suicide he identified are based on the degrees of imbalance of two social forces: social integration and moral (cultural code) regulation:

- Egoistic suicide is suicide that results from a chronic condition of dis-integration, of not belonging in any social group. This experience erodes the individual’s ability to produce meaning.

- Altruistic suicide is somewhat the opposite of the first situation. It describes someone opting out of life because the social environment leaves no space for his individual existence. Only the group’s needs are addressed.

- Anomic suicide is a result of a state of critical disruption of the social fabric itself, to a point that there are no normative principles for the individual to construct his own set of guidelines and goals.

- Fatalistic suicide is at the other side of the spectrum from anomic suicide and happens when the social norms and constraints are violent and oppressive enough to suppress all the individual’s passions and goals. Examples would be forced marriages, prison, sexual slavery, etc.

Pridmore et al (2009) suggests that there are two types of suicide: those where the mental illness itself and its episodes are the triggers for the suicidal act and those where the major trigger is a social event from the environment. Milner et al (2012), in a cross-sectional study including 35 countries, suggested that variables related to the labor market and the economy were better explanatory factors of suicide rates than population-level indicators of interpersonal relationships. Pridmore’s group mention great financial loss, unemployment, shame, terminal painful chronic disease, etc.

Finally, some individuals, for different reasons, display a suicidal inclination in early childhood. It may sound scary, but the proportion of normal children who entertain suicidal ideation and actually attempt suicide is not negligible: a study of 101 preadolescent school children, who had never been psychiatric patients, Pfeffer et al (1984) found 11.9% with suicidal ideas, threats, or attempts. Another research group carried out a seven-year study with 505 children and adolescents who had attempted suicide. They differed from the controls according to both mental illness and social environment variables (Garfinkel and Hood 2006).

It is in the interface of all that that suicide is important for us, in this series of articles on motivation.

Escape from Self, Uniqueness, and Belonging

We started part one with the question “who am I?” and ended part three with the conclusion that hope can be provided by the social environment. All along, we are talking about individual and collective identity and about individual and collective selves.

If we look back a few paragraphs above, the four suicide types identified by Durkheim in the XIXth century refer also to this tension between the individual and collective identities under the idea of social integration.

Under smothering social environments where individual goals, passions or needs are not acknowledged, or under oppressive and violent societies where they are denied, there is no space for the construction of motivation; passion cannot exist, by definition, and hope is either lost or may never emerge, since there are no goals in reference to which build a desired outcome.

What these patterns seem to suggest is that the conditions that are conducive to a motivated, passionate and hopeful individual are those compatible with his psychological well-being, while the opposite is also true.

Several different schools in psychology have described the basic human urge for connectedness, relatedness, and intimacy (Hornsey and Jetten 2004, Berne 1968). Among them, some have argued in favor of belonging (creating bonds) and others of uniqueness (differentiation) as more important, right under the basic subsistence needs (like satisfying hunger). Both approaches rely on the assumption that individual identity is achieved at the expense of the group (collective identity) and vice-versa.

Unfortunately, in history, the opposition between the group and the individual—satisfaction of needs, goals, values, principles, etc.—has been highly ideologized. Many schools consider that the external motivation to succeed over others (competition) is something essentially “wrong” and harmful to the group’s well-being.

Fortunately, research has been offering a wealth of evidence concerning these facts: the need for uniqueness (or individual identity), the need for interpersonal relatedness, and the need to group belonging (collective identity) are ubiquitous and universal.

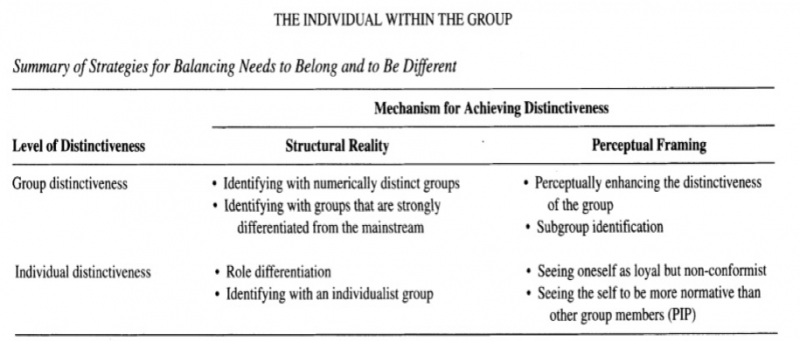

Vignoles et al (2000) concluded that, "a pervasive human motivation exists to see oneself as distinctive, which derives from the importance of distinctiveness for meaningful self-definition." Hornsey and Jetten (2004) attempt to offer a model where the two apparently conflicting urges (to be different and to belong) are balanced in such a way that individuals’ need for uniqueness does not violate social identity principles. The table below summarizes the four strategies from their model:

From Hornsey and Jetten 2004.

Pick a quadrant. Let’s say “group distinctiveness” X “structural reality.” There you go: powerlifting! It is small (“numerically distinct”) and “strongly differentiated from the mainstream.” We can apply this model to many “uniqueness X belonging” real life situations.

If the self needs to exist in and for itself and in relation to other individuals and groups, it is not hard to associate suicide to an attempt to escape from a self that is seen as incompatible with both (or the three) basic needs. This is what Baumeister (1990) called an “escape from aversive self-awareness,” or “an ultimate step in the effort to escape from self and world.”

Motivation, Goals, and Purpose

While most people take for granted the deeper answer to the question, “why do you lift?”, many of us will be forced to come up with our individual answer at some point or another of our athletic careers. This is usually unpleasant and a result of some type of catastrophic event.

We may have to go back to square one and redesign our goals, their time frame, their magnitude, and their nature. Our passions and motivations may have to be restructured. And for some of us, a different motivator may emerge: purpose.

Purpose is somewhat related to goal, but differs from it by not having a time frame, markers, and a precise result. It is closer to the idea of “intention.” In our context, purpose is an intention that encompasses but transcends individual goals.

It is not surprising that purpose and purposeful activities are protective against suicide and also conducive to the reconstruction of destroyed foundations of an individual’s existence. “Higher purposes” such as social work, religious involvement, and even ideology can provide that. Apparently, the long-term or atemporal nature of the purpose is a factor in the resilience of individuals facing hardship.

PART 3: Why Do You Lift — Defining Hope, Motivation, and Risk

For the athlete, embracing a higher purpose—teaching, helping vulnerable individuals through sport, charitable events, etc.—may be the consequence of a deeper involvement with the sport and will keep him connected to it much longer than his golden competitive years would.

Hopelessness and the Recovery of Hope

The single most important predictive factor for suicide is hopelessness (Pompili et al 2006, Beck et al 1999, Chioqueta and Stiles 2005, Weishaar and Beck 1992). Let us recall the meaning of hope: hope reflects the belief that it is possible to find pathways to desired goals and become motivated to use those pathways (Snyder et al 2002, in part three). It is a combination of waypower (identifying a pathway to achieve the desired goal) and willpower (believing one is capable of following that pathway).

Hopelessness reflects the opposite belief: either there is no way to achieve a goal, or, if there is, the individual sees himself unable to follow it. As hope includes the ability to envision alternative routes when confronted with the failure of the first chosen pathway (plans B, C and D), hopelessness reflects either the actual impossibility of any other pathway or the subjective choice of giving up pursuing any further, for any internal or external reason.

As hope was related to goal setting, hopelessness reflects the inexistence of concrete goals.

There are examples of individuals who rebuilt the whole motivational building, which now we know is made of many complex parts, from scratch. They returned from combat with missing limbs, missing functions, or missing sanity. Others returned from abuse, rape or some other horrific trauma.

I would like to go back to the woman who slashed her throat on the dirt road. When she was running aimlessly on the beach, she had no goals, no motivation, an individual and social identity in rapid course of erosion, no passion, and was unable to have hope. Her last resources to take action were, as predicted by Baumeister (1990), employed to strip away inhibition and irrationally take an impulsive measure to leave herself and the world.

Of course, this happened under a situation of external triggers (long, medium and short-term) and a history of mental suffering. Most suicidal individuals under these circumstances act in deep ambivalence, on what is sometimes called “mixed state” or “rapid cycling” (Benazzi and Akiskal 2005, Balázs et al 2006, Wu and Dunner 1993, Garcia-Amador et al 2009) — two different concepts, but both related to suicide risk. During such an ambivalent suicidal attempt, the individual alternates between the intention to act on the suicidal ideation and its rejection, the wish to die and confusion and doubt.

And that was it. I survived the slash and almost immediately established a goal: as I admitted that whatever I had was stronger than I thought, I decided to understand it rather than dominate it. Plan A, to dominate and quench whatever I had, failed and I came up with a plan B. A hierarchy of goals unfolded before me: to solve this puzzle, I needed to survive; for that, I needed to train and document all relevant variables; for that, I needed to get back to Sao Paulo.

That was when I designed my first strength training program, one adjusted for a suicide survivor with limited upper limb movement.

When I finished the six-week program on my computer, I had short, medium and long-term goals, I had pathways to achieve them, and I believed I could do it.

I had hope.

With hope, I recovered passions — harmonious and obsessive, both.

And with the first “perfect lift”—that timeless and spaceless pure expression of strength—I learned what transcendence was.

Then, I didn’t care any more about life or death.

Maybe that’s why I’m still alive.

References

- Balázs, Judit, et al. "The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: implications for suicide prevention." Journal of affective disorders 91.2 (2006): 133-138.

- Baumeister, Roy F. "Suicide as escape from self." Psychological review 97.1 (1990): 90.

- Beck, Aaron T., et al. "Suicide ideation at its worst point: a predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients." Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 29.1 (1999): 1-9.

- Benazzi, Franco, and Hagop Akiskal. "Irritable-hostile depression: further validation as a bipolar depressive mixed state." Journal of affective disorders84.2 (2005): 197-207.

- Berne, Eric. Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. Vol. 2768. Penguin UK, 1968.

- Bertolote, José Manoel, and Alexandra Fleischmann. "A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide." Suicidologi 7.2 (2015).

- Bostwick, John Michael, and V. Shane Pankratz. "Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination." American Journal of Psychiatry 157.12 (2000): 1925-1932.

- Chioqueta, Andrea P., and Tore C. Stiles. "Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation." Personality and individual differences 38.6 (2005): 1283-1291.

- Durkheim, Emile (1897) [1951]. Suicide : a study in sociology. The Free Press

- Fleischmann, Alexandra, et al. "Completed suicide and psychiatric diagnoses in young people: a critical examination of the evidence." American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 75.4 (2005): 676.

- Garcia-Amador, Margarita, et al. "Suicide risk in rapid cycling bipolar patients." Journal of affective disorders 117.1 (2009): 74-78.

- Garfinkel, D., A. Froese, and Jane Hood. "Suicide attempts in children and adolescents." The American Journal of Psychiatry 76.36.5 (1982): 12.

- Hornsey, Matthew J., and Jolanda Jetten. "The individual within the group: Balancing the need to belong with the need to be different." Personality and Social Psychology Review 8.3 (2004): 248-264.

- Joiner Jr, Thomas E., Daniel Hollar, and Kimberly Van Orden. "On Buckeyes, Gators, Super Bowl Sunday, and the Miracle on Ice:" Pulling together" is associated with lower suicide rates." Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 25.2 (2006): 179.

- Kessler, Ronald C., Guilherme Borges, and Ellen E. Walters. "Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey." Archives of general psychiatry 56.7 (1999): 617-626.

- Kessler, Ronald C., Guilherme Borges, and Ellen E. Walters. "Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey." Archives of general psychiatry 56.7 (1999): 617-626.

- McLean, Joanne, et al. "Risk and protective factors for suicide and suicidal behaviour: A literature review." (2008).

- Milner, Allison, Rod McClure, and Diego De Leo. "Socio-economic determinants of suicide: an ecological analysis of 35 countries." Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 47.1 (2012): 19-27.

- Pfeffer, Cynthia R., et al. "Suicidal behavior in normal school children: A comparison with child psychiatric inpatients." Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 23.4 (1984): 416-423.

- Pompili, Maurizio, et al. "Hopelessness and suicide risk emerge in psychiatric nurses suffering from burnout and using specific defense mechanisms." Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 20.3 (2006): 135-143.

- Pridmore, Saxby, Jamshid Ahmadi, and Anil Reddy. "Suicide in the absence of mental disorder." Australasian Psychiatry 17 (2009): 233-236.

- Pridmore, Saxby. "Predicament suicide: concept and evidence."Australasian Psychiatry 17.2 (2009): 112-116.

- Taliaferro, Lindsay A., et al. "High school youth and suicide risk: exploring protection afforded through physical activity and sport participation." Journal of School Health 78.10 (2008): 545-553.

- Tomori, Martina, and Bojan Zalar. "Sport and physical activity as possible protective factors in relation to adolescent suicide attempts." International journal of sport psychology (2000).

- Vignoles, Vivian L., Xenia Chryssochoou, and Glynis M. Breakwell. "The distinctiveness principle: Identity, meaning, and the bounds of cultural relativity." Personality and Social Psychology Review 4.4 (2000): 337-354.

- Weishaar, Marjorie E., and Aaron T. Beck. "Hopelessness and suicide."International Review of Psychiatry 4.2 (1992): 177-184.

- Wu, Lynne H., and David L. Dunner. "Suicide attempts in rapid cycling bipolar disorder patients." Journal of affective disorders 29.1 (1993): 57-61.

2 Comments