Back to the Future, an excerpt from liftSTRONG. I want to say this was written in 2003-2004 but I am not really sure.

I was honored to be part of an illustrious group of authors pulled together by Alwyn Cosgrove to write segments for his liftSTRONG project. All the proceeds from this project were donated to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. I’m including my part in it in hopes that you’ll get involved.

This was then posted as an excerpt in my book Raising The Bar.

An excerpt from the movie Back to the Future, starring Michael J. Fox and Christopher Lloyd.

Dr. Emmett Brown: So tell me, Future Boy, who’s President of the United States in 1985?

Marty McFly: Ronald Reagan.

Dr. Brown: Ronald Reagan? The actor?! Who's Vice President? Jerry Lewis?

Amazon.com video review of the movie Back to the Future:

Filmmaker Robert Zemeckis has topped his breakaway hit, Romancing the Stone, with this joyous comedy with a dazzling hook—what would it be like to meet your parents in their youth? Billed as a special-effects comedy, this imaginative film (the top box office smash of 1985) has staying power because of the heart behind Zemeckis and Bob Gale's script.

High schooler Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox during the height of his TV success) is catapulted back to the ‘50s, where he sees his parents in their teens and accidentally changes the history of how mom and dad met. Filled with the humorous ideology of the ‘50s and filtered through the knowledge of the ‘80s (actor Ronald Reagan is president, ha!), the film comes off as a Twilight Zone episode written by Preston Sturges. It’s filled with memorable effects and two wonderfully off-key, perfectly cast performances—Christopher Lloyd as the crazy scientist who builds the time machine (a DeLorean luxury car) and Crispin Glover as Marty’s geeky dad. Followed by two sequels. —Doug Thomas

What does this have to do with weak points?

What, you’re probably asking, does this movie have to do with addressing weak points? In order to understand this fully, we must first define weak points.

Anything that keeps you from getting what you want is a weak point. In sports and training, these are mental, technical or physical. These can be described in a complex manner, but I always find it better to fall back on my experience when discussing training. For more than three decades, I’ve trained with and competed against many of the best lifters in the world. All the success I’ve had and everything I’ve learned from these experiences can be attributed to overcoming weak points.

The trick is how to pass all of this on to you in a way you’ll remember. It needs to be done in a way that will stick, and it has to be something you can actually use. I think the information contained here can completely change the way you see training, and it can lead to greater results than you’ve ever thought obtainable. The problem, however, is sharing it in a way that gets you to remember it.

This is where Back to the Future comes into play. This movie, combined with a few stories I’ll share, will act as a trigger to help drive some simple concepts home. When a concept is tagged with a trigger, it becomes very powerful. Since we’re going with a Back to the Future theme, let’s catapult back in time and see how this will affect your future.

Let the journey begin.

Marty McFly: What if I send it in and they don't like it? What if they say I'm no good? What if they say ‘Get out of here, kid. You got no future.’ I mean, I just don't think I can take that kind of rejection. Jesus, I'm starting to sound like my old man!

January 1975

After we all watched Pittsburgh beat Minnesota 16-6 in Super Bowl IX, all the kids in the neighborhood went outside to play our own version of the game. I still remember my heroes like it was yesterday—Harris, Bleier, Bradshaw, Swann, and Stallworth. These guys were like gods to us. They were who we all aspired to be. They were warriors on the gridiron, and we felt connected to them.

In our muddy lot that day, our hits were harder, our passes were longer and our runs were faster. We gave it our all, and nothing was going to stop us. Day turned to dusk, and we kept going. The air grew colder, and with it, the ground got harder, but for this group of back-lot kids, it was the best day of our lives. I was having an incredible time. I was much younger and smaller than the rest, but I stood my ground and gave it my all.

On third and long, a play was drawn in the mud. This bomb was going to me! This was it, my chance to be just like Lynn Swann. When the ball was snapped, I took off as fast as I could. I remember running with everything I had, feeling like I played for the Steelers. Fifteen yards down the field, I was wide open. After ten more yards, the ball was in the air, and it was heading my way. This, finally, would be my day. It would be the day where the other kids would stop seeing me as the “last pick.” This was my destiny.

As I turned for the ball, I heard something snap and I fell to the ground. My foot had gotten caught in a storm drain, and I’d twisted my ankle. I sprawled out in the mud with the rest of the kids standing around me.

“Loser! Pussy!”

There I was, face-down in the mud, and they were kicking dirt in my face.

I pulled myself to my feet and headed home. When I walked into the house, with tears in my eyes, my mother suggested that I take a bath. I began heading off to the bathroom to start the water.

My dad had never moved from his chair. He’d seen me limp in the house, and he asked me to come into the front room with him. My tears intensified as I trailed mud through the house. My ankle was painful, but that’s not why I was crying. All I wanted was my father’s support. I wanted for him to tell me how bad the rest of the kids were.

“Is the game over?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. I told him that I’d gotten hurt and had to come home.

“Is the game OVER?” he asked again.

I didn’t know what to say to this or what to think. “Pain is part of the game,” he said. “Live with it.”

He then proceeded to tell me to put my coat on and go back out and finish the game.

This scared the shit out of me. I could barely walk, and I didn’t want to go back to the abuse. My father insisted, however, and I found myself caught between a rock and a hard place. Next thing I knew, I was back outside finishing the game.

As before, you’re probably asking yourself what this story has to do with overcoming weak points. Then again, you may think you’re already figured it out. Maybe this motivated you. Maybe it reminded you of your past. Maybe it confirms your belief that you have to play with pain.

Maybe, however, you’re all wrong.

What this story illustrates is that my dad is the reason for all the injuries I’ve suffered over the years. He’s why I push harder when I’m hurt. He’s the reason why I’ve pushed so hard all along, and the reason why I’ve never rested long enough. If it wasn’t for him, things would have been very different.

Do you buy this load of crap? If you do, then why do all of you do the same thing every day?

The first rule of addressing weak points is to understand that they’re YOUR problem caused by things that YOU did or didn’t do.

Got it?

Marty McFly [being chased by terrorists]: Let's see if you bastards can do 90.

June 2003

Along with my family, I finally moved into my dream lake house. Within minutes, I can be fishing off my dock. I still remember my first trip down to the dock with my fishing pole and worms. I tossed the line out, reeled back in, then tossed it back out again. After a few repetitions of this, I felt the line pull. Then it pulled again. It had been twenty years since I’d fished, and I’d forgotten the rush you get when something tugs on your line.

Moments later, I had a fish! I was jacked up beyond belief, and I felt like the best fisherman in the world. In actuality, I was the best fisherman on my dock. I was the most advanced one there, and I may have been the most advanced fisherman on the lake for all I knew. Fact was, I knew all I needed to know for the circumstances I was in.

Later that summer, my father-in-law came over with his pole and a huge tackle box filled with gear. In no time flat, he was pulling in fish left and right. All of the sudden, I didn’t know anything, and I was no longer “advanced.” I was back to being a beginner.

Ironically enough, the entire time he was teaching me the fishing game, he’d been telling me about a trip he’d just taken to Lake Michigan, and how this fishing guide made him feel like he didn’t know anything. This was interesting to me because he was describing exactly how he was making me feel.

He was a far better fisherman than I was, and he had the benefit of years of experience. How could we both have been beginners?

This is a very simple concept that everyone seems to miss. Your status depends on your surroundings, not what you know or what you’ve done. If you ask me whether you’re a beginner, I’ll ask you where you’ve trained and whom you’ve trained with.

Here’s how this relates to overcoming weak points. Think about anything you’ve ever done. When did you have the highest rate of success in proportion to the rest of your results? When you were a beginner, that’s where. The beginner always makes faster gains than the advanced guy. ALWAYS. If you want to keep making progress, always place yourself in the role of the beginner. If you’re the strongest guy at your gym, find stronger people to train with. When you become the strongest there, find someone else. There are always stronger people out there, so seek them out.

Have you ever wondered why people advance so fast in small powerlifting gyms? It’s because the top dog has the bigger bite.

Always find people who are better than you.

Dr. Emmett Brown: Don’t worry. As long as you hit that wire with the connecting hook at precisely eighty-eight miles per hour the instant the lightning strikes the tower...everything will be fine.

1050 B.C. (approximately)

Goliath was a Philistine champion from Gath. He was a giant of a man, measuring over nine feet tall, and he came out of the Philistine ranks to face the forces of Israel. (1–1 Samuel 17:4)

Goliath stood and shouted across to the Israelites, “Do you need a whole army to settle this? Choose someone to fight for you, and I will represent the Philistines. We will settle this dispute in single combat!” (1 Samuel 17:8)

As he (David) was talking with them, he saw Goliath, the champion from Gath, come out from the Philistine ranks, shouting his challenge to the army of Israel. (1 Samuel 17:23)

He picked up five smooth stones from a stream and put them in his shepherd’s bag. Then, armed only with his shepherd’s staff and sling, he started across to fight Goliath. (1 Samuel 17:40)

Goliath walked out toward David with his shield bearer ahead of him. (1 Samuel 17:41)

“Come over here, and I’ll give your flesh to the birds and wild animals!” Goliath yelled. (1 Samuel 17:44)

As Goliath moved closer to attack, David quickly ran out to meet him. (1 Samuel 17:48)

Reaching into his shepherd’s bag and taking out a stone, he hurled it from his sling and hit the Philistine in the forehead. The stone sank in, and Goliath stumbled and fell face downward to the ground. (1 Samuel 17:49)

He ran over and pulled Goliath’s sword from its sheath. David used it to kill the giant and cut off his head. When the Philistines saw that their champion was dead, they turned and ran. (1 Samuel 17:51)

The stronger athlete doesn’t always win. He’s not always the best. Neither is the most functional, mobile or flexible, or the fastest or the one with the most endurance. The best athlete is the one who’s best at what he or she does.

Let’s take a step back and define some things. General Physical Preparedness (GPP) entails performing movements to help improve your level of conditioning. Specific Physical Preparedness (SPP) involves performing specific skills to improve your performance in your chosen sport. Bottom line, the better the SPP, the better the athlete. The best athletes will excel at the SPP associated with their sport. David beat Goliath because his fighting skills were better. He wasn’t the strongest, but he was the most skilled.

There are three lessons here, and each can be applied to a different segment of the population. If you’re an athlete, are you working on your skills? I mean all the time, not just in practice. These skills are the most important part of your game. For lifters, this means technique. If you ever get the chance to watch an elite powerlifter compete, you’ll see what I mean.

It’s very clear what needs to be done. Athletes of lesser skill are overly concerned with the training programs and equipment used by the top guys, and they can’t see what’s right in front of their faces. I’ve seen technical adjustments put a hundred pounds on a lift. Do you have any idea how long it takes to get a hundred pounds stronger? Not nearly as long as it takes to make your technique better.

If you’re a strength coach or a trainer, have you spoken to your athletes’ positional coaches? Be honest, now. Have you called them or met with them? If you’ve been hired to make athletes better, why haven’t you done the one thing that could have the greatest effect? Think about this for a minute. You have everyone do a warm-up, right? What if this warm-up consisted of skill drills that their positional coaches feel would help them the most? If you do this, your athletes can work these skills, under supervision, multiple times throughout the entire off-season. Do you think this might have an effect on their game?

If you don’t know a skill, don’t perform it, and don’t teach it. The worst thing an athlete can do is to reinforce incorrect skills or patterns. As a coach, the worst thing you can do is try to teach what you don’t know, or worse yet, what you think you know, but don’t.

Take squatting, for example. The injury rate for competitive powerlifters in the squat is extremely low. In fact, compared to other sports, the total injury rate for competitive lifters is very low. Rarely do competitive lifters miss squat sessions—otherwise known as “practice” —or incur injuries performing this lift. Despite this, many coaches and trainers will tell you NOT to squat for fear of injury. This tells me these coaches and trainers have no idea how to teach this lift. Therefore, they shouldn’t use it.

Teach what you know, and learn what you don’t.

George McFly: Last night, Darth Vader came down from planet Vulcan and told me that if I didn’t take Lorraine out that he’d melt my brain.

June 1999

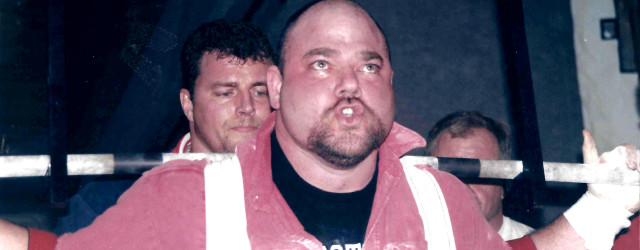

The IPA Worlds, also known as the York Barbell Hall of Fame Meet, was my first powerlifting meet back from a nine month hiatus. I had taken some time to heal, regroup and gain some weight. I’d been looking forward to this meet because my training was going very well, and things seemed to be going my way.

As often happens, the meet’s start time was pushed back. The 308 pound class wouldn’t be starting until five in the afternoon, three hours later than originally planned. Well, 5:00 became 6:00, and 6:00 became 7:00. Finally, at around 7:30, we started warming up and getting ready for our squat attempts. My warm-up felt fast and explosive, and I was definitely in the process of getting “jacked up” about the meet.

“Dave Tate on deck,” was called over the loudspeaker as I sat in the pit waiting. This was my signal to begin focusing on the task at hand. One of my helpers started getting my wraps and everything else ready to go.

I stood with one helper on either side of me. They pulled my straps out, helped with my belt, smacked me in the back of the head and stuck an ammonia cap up my nose. These times, right before I hit the chalk, count among the best moments of my life. You simply can’t match the anticipation, the aggression, and the work it took to get there. It’s unmatched.

“Load the bar to 860 pounds for Dave Tate.” This was my opening attempt. I’d squatted it several times before.

Enraged, I chalked my hands. This is the moment that comes with every big lift where I “detach” from myself. I rarely remember anything from the time I leave the chalk box until after the lift. I’ve been at this point so many times that all I have to do is get in state and switch into autopilot.

This lift, however, is one I would remember. I couldn’t get the bar out of the rack. I remember trying to stand up with the weight, but I couldn’t budge it. It felt as though it was welded to the rack. I tried a few times, but nothing happened. This pissed me off to no end, so I stepped back, got even more enraged, then tried it again. Still, nothing.

My helpers stepped in and pulled me away from the rack. This was not a good moment for me. Nine months of training, and I couldn’t get my damned opener out of the rack. My helpers pulled me back into the warm-up room, and we tried to figure out what the problem was.

“Dave,” said one of my training partners, a guy I trust with my life, “you’re done. Pull out.” I thought he was just trying to piss me off, but he meant what he was saying. “Seriously, you’re done. Pull out, and we’ll talk later. It’s not worth what could happen right now.”

The man who said this was, and still is, one of the best coaches in the world, and I was part of his team. The Westside Barbell Club. It’s the strongest gym in the world, and I was one of “Louie’s Boys.” Perplexed, I pulled out of the meet and ate hot dogs while the rest of my team went on to lift well.

What the hell was my problem?

Why can’t I have just one good meet?

What the hell was I missing?

What was my weakness, and how could I fix it?

Driving home, I told Louie that I didn’t understand what had just happened. My training had gone well, and I was as strong as hell on everything in the gym. He replied by telling me something I’ll never forget.

“That,” he said, “is exactly what the problem is.”

I thought he was out of his mind. How could being strong in the gym possibly be a bad thing?

“You know what you need?” Louie asked, turning onto the interstate. “You need to do the things you suck at. You’re at a point where your weaknesses are killing you, and you’re doing nothing to address them. Your legs can easily squat a grand. Your upper back can easily support it, but your abs and lower back can’t hold the weight right now. You have some muscles that can squat a thousand pounds, but others that can’t squat 860. What do you think that will make you squat? What you need to be doing are reverse hypers and standing ab work!”

In training, I hated doing reverse hypers, and I hated doing standing ab work. As a matter of fact, I hated all lower back and ab work, so I didn’t do much of it. To be perfectly honest, I skipped it most of the time.

You see, if you have a weak point, there’s a very good reason for it. It’s caused by not doing the stuff you don’t like to do.

This is the difference between competitive athletics and “working out.” You can always get into better shape by doing things you like to do, but to excel at a sport, you have to master the things you hate.

For the next six months, I trained my lower back and abs four days a week, at the beginning of every session and at the end. At the Nationals in November, I squatted my first 900 pounds. For my next meet, I increased my torso training to six days a week. Three of these were very heavy, and three were light. In July, at the same meet I pulled out of the year before—the IPA Worlds—I squatted 860 pounds, then 905, and then an easy 935. In training for this meet, my main gym lifts—the ones I’d bragged about the year before—were actually down fifteen percent from the previous year. My torso, however, was the strongest it had ever been.

Weak points are developed by NOT doing the stuff you suck at.

George McFly: Uh, well, I haven’t finished those up yet, but you know I...I figured since they weren’t due ‘til...

November 2002

This was the second year that EliteFTS had hosted the IPA Nationals. It’s always nice to give something back to the lifting community, but hosting a meet entails months of hard work and preparation. With everything in order, I decided to take my family on vacation a couple of weeks before the event. This would give us some time to get ready to put on the best competition we could for the lifters.

Right before we left, Chuck Vogelpohl rolled his car into a ditch. I only knew about this because the police officer on the scene brought Chuck to the gym so he wouldn’t miss his squat workout. Chuck was training for the meet and didn’t want to miss a session despite the scrapes and bruises he had from the accident. He also still had to find a way home, but none of this ever dawned on him. All he knew was that he had to do what he had to do.

When I came back from vacation and returned to the gym, a teammate came up and asked me if I’d heard about Chuck. Figuring this was old news by this point, I said, “Yeah. He rolled his car before I left.”

“No, no, no, Dave. He rolled the rental car three days ago.”

“You have to be kidding me,” I thought to myself. How in the world can you roll two cars within ten days, especially when you have two weeks left before an important meet? Not long after this, Chuck walked into the gym carrying his bag, and started getting ready for his last bench session before the meet. He was covered with new scrapes, cuts and bruises to go with the old ones from the week before. I asked him how he felt.

“Real good,” he said. “Only one week to go.” Not one word was ever said about the second accident. It didn’t occur to Chuck to talk about it. All he knew was that he had to do what he had to do.

The meet started off perfectly. Everything was set up, the lifters seemed happy, and the women and the lightweights were getting ready to start. Chuck limped in holding a gallon of water. He was there to weigh in, and he’d be lifting the following day. I asked him how the weigh-in had gone, and he told me he’d made weight and was ready to go. He said he was limping because he’d pulled a glute, but that it was no big deal. He said he’d have a good day tomorrow.

The guy had been in two car accidents in the past two weeks, and he showed up to the meet with bruises up and down his right leg. Then, somehow, he managed to pull a glute two days before the meet. What the hell was he even doing there? Of course, this never dawned on him. All he knew was that he had to do what he had to do.

The following day, I was sitting in the head judge’s chair. In addition to running the meet, I’d be judging it as well. The only break I’d get from judging was when my teammates or friends would lift. When that happened, I’d step out and let someone else judge.

I took a look at the lifting order and noticed that Chuck’s opening squat attempt was 900 pounds. I was confused, so I flagged down Louie Simmons to ask him what the hell Chuck was doing. His best squat to date was 860 pounds, so he’d be opening with a 40 pound personal record.

“Yeah, well, you tell him,” said Louie.

I’ve known Chuck for many years, and I knew he wouldn’t listen even if I did tell him. Nothing I said would have mattered, because he had to do what he had to do.

Chuck screamed out for his opening attempt, and I mean screamed. He’s known as one of the most intense lifters in the history of the sport. He may not be loud, but his intensity is contagious. When he lifts, he has that “something” that I’ve only seen in a couple of other lifters. He’s also a huge crowd favorite, so when he approaches the bar, the crowd stands and roars. His rage and intensity can be felt by everyone in the room.

He set himself under the bar and began to descend. And descend. And descend.

He never got back up. He just got, as we say in the game, “stapled.” He missed the weight, and I felt bad for him. After all he’d been through, it sucked to have things end like this. I figured he’d probably learn from this and pick his openers better next time. As I headed back to the judge’s chair, I heard Louie call Chuck for a repeat. In a meet, you get three attempts. If you miss one, you can keep the weight the same or you can go heavier, but you can’t lower it. Chuck had decided to give it another shot.

After getting stapled trying for a 40 pound personal record, most lifters would have pulled out. Chuck, however, just did what he had to do.

The next time I saw Chuck’s name come up on the lifting order board, I noticed that he’d increased his second attempt to 950 pounds. This would be the second highest squat of all time, and a weight class record in this federation. This call amazed me, but as his friend and teammate it also concerned me. I called Louie over and asked him again what the hell was going on.

“You go tell him,” Louie replied.

I was about to lose my mind. I wasn’t going to be able to go tell Chuck anything, because I had to stay where I was and judge the meet. I told Louie that he had to say something.

As evidence, I reminded Louie of Chuck’s two car accidents, his pulled glute, and the fact that he’d been smashed on his opener. Louie wasn’t going to say anything, however, so I went into the warm-up room to find Chuck myself. He was sitting in the corner. His helpers were rubbing out his quads, and his eyes were focused on the ground. He looked up and caught my eye.

The look in his eye told me that it didn’t matter what I was about to say. He was going to do what he had to do.

When Chuck came out, he was as intense as I’ve ever seen him. The crowd was in its feet, and the music was cranked as loud as it could go. For a moment, I actually thought he might have a chance.

Chuck grabbed the bar and set his hands. He put his right foot in place, then his left. Finally, he ducked under the bar and prepared to unrack a world record weight.

He set the weight up and filled his chest and torso with as much air as he could. Making a slight hip adjustment, he pulled his head up and began to sit back into the squat. As he lowered the weight, I had a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach, and my primary concern was simply that he not get hurt.

Then he hit parallel and blasted the weight up like the bar was empty. This was one of the most impressive lifts I’ve ever seen.

For his third attempt, Chuck called for 970 pounds, which would be the highest squat of all time for his weight class. He then changed his mind and called for 1000, which would make him the lightest man to ever squat a grand.

Did he do it?

What do you think happened with the man who just had to do what he had to do? And what do I mean by saying he had to do what he had to do, anyway?

Let me explain something to you. The only difference between the professional athlete and the weekend warrior is that the professional athlete does the right things more frequently than the weekend warrior does. Every golfer will tell you about the great shots they’ve made, but the professionals do it more often. This can be applied to any sport.

Why is this the case? Well, like Chuck, most successful people live in the present. It’s very easy to write out and plan goals. It’s easy to find a diet to follow and a training program to stick to. It’s also very easy to sit back and bask in the glory of the past. It’s a completely different thing, however, to live it all right now.

The decisions most athletes focus on involve what they’ve done in the past or what will affect their future. In reality, however, the past is nothing more than a bunch of presents that have already happened. The future is a bunch of presents yet to happen. In other words, you can’t change the past, and you can’t predict the future. You can, however, control what you do right now.

Are you on a diet? If you are, is it time to eat again? Are you eating the right stuff? The last time you trained, did you do what you needed to do? Or what you wanted to do? Your future is made up of all these “present” decisions.

This is doing what you have to do.

It would be very easy to write a weak point training article that discussed the proper execution of certain lifts, or one that gave you a bunch of special exercises designed to bring up weak muscle groups. Changes like these, however, are only major to lifters who are already at the top of the game. For the other ninety percent of you, thinking about and applying the concepts I’ve discussed can have profound effects immediately.

The process of training is not an easy one. Anyone who tells you it is has obviously never done it. These are the same people who’ll claim others’ success is due to genetics, drugs or some other shortcut. In reality, there are no shortcuts.

Talk to someone at the top, and ask them how long it took to get there. Ask them what sacrifices they had to make.

How do you know whether you don’t have good genetics if you don’t give it all you have? What if after a year or two of training, someone tells you that you don’t have the genetics? Do you buy this load of crap? Show me anyone who has excelled at his or her sport in only two years.

Do you honestly think that changing your health and body composition won’t take a supreme effort and a ton of sacrifice? If you do, then you’ll have to wake up.

Do you think that becoming the best coach or trainer in the world can happen from behind a keyboard? If you do, then you’ll have to wake up.

Everything worthwhile in life revolves around the overcoming of weak points. Weak points are adversity. The reality is that most people suck at this, and they’ll always suck at it because it requires honesty and growth, discomfort, and living in the present. It’s far easier to be a lazy liar who dreams about the future and blames the past on everyone else.

1 Comment