If you plan to have a strength and conditioning career, you need to start interning as soon as possible. Once graduation rolls around, having experience will help set you apart from other candidates when looking to secure a Graduate Assistant position. Just going to class and getting the degree isn’t going to cut it. Hell, you may even find out you don’t like the politics of collegiate strength and conditioning, and perhaps you’d rather run your own private training facility. The only way to know for sure is to get hands-on experience and find out.

From 2016-2019, I was simultaneously completing two internships at both Roland-Story High School and Iowa State University. During that time, I learned valuable coaching skills and life lessons I could never learn in the classroom. These lessons listed below will be helpful to those starting an internship and those who might need to light a fire under their ass and refocus their efforts. Below are 18 lessons I learned during my first three years interning in the weight room.

1. Find Opportunities to Expand Your Knowledge

If you want to succeed in strength and conditioning, you need to have a wide knowledge base. Yes, some of this knowledge comes from books, but most of your learning should be hands-on working under experienced coaches. Conferences are great events to learn from experts in the field. When there is not a pandemic going on, conferences also provide opportunities to network and make connections. By going to a state NSCA conference, I landed my first internship. I recognized one of my professors in the audience and went over to talk to her at the end of the conference. As it turned out, her husband was the strength coach at a local high school. We began talking, and a month later, I started interning.

MORE: The elitefts Internship Guide

About eight months later, I went to a USA Weightlifting certification because I was not well versed in the Olympic lifts and wanted to better myself. In hindsight, I recommend finding an expert near you who can teach you the Olympic lifts as this will be much less expensive and give you experience. By no means does having a certification from a weekend class make you an expert, but it does show that you care enough to go out of your way to learn and grow.

2. Come Into the Internship With as Much Knowledge as Possible

Even though the point of an internship is to gain hands-on experience and learn, it never hurts to be prepared. Especially if an internship has a large pool of applicants, knowledge will be a powerful advantage during the interview phase. Walk in as prepared as possible and with an open mind. You won’t be expected to know everything; however, the coaches will respect you for not being a complete idiot. The faster you make it through their internship curriculum, the sooner you will be given responsibilities other than cleaning the weight room.

3. Spend as Much Time as Possible in the Weight Room

You gain from the internship what you put into it. You’re not going to learn much if you’re only there five hours per week. Every morning that teams are there, you should be there too. Every moment that you are not in class, you should be in the weight room. If the strength coaches allow you to lift with them, you should be there.

I arranged my classes each semester so that I was able to lift with the strength coaches every single day. Having experienced strength coaches as your training partners will be far more beneficial than the random gym bro you ask to spot you. Experience under the bar is the best experience, and it will help you avoid ridiculous programming mistakes (such as “Clean & Jerk 3x6 @ 90%” for your future athletes). If you think that doesn’t sound too bad, give it a try and report back to me.

4. Caffeine is Your Friend

You will probably develop a caffeine addiction; this is normal. Waking up at 4:30 AM every day gets tiring, even if you have a habit of being in bed by 9 PM. Coffee, energy drinks, and caffeine pills are all acceptable. Just try to stop consuming caffeine by 3 PM if you want to sleep restfully.

5. Ask Questions

Aside from actual hands-on coaching, this is one of the best learning aids at your disposal. The strength coaches you work for have many years of experience under their belt. Pick their brains. Even if it’s a question they have answered dozens of times for past interns, you should ask if you don’t know. Now, if you keep asking the same question over and over again, don’t be surprised if the strength coach stops answering you. Furthermore, try to ask good, in-depth questions that will lead to a full-blown conversation. Perhaps you’ll even ask a good question they haven’t heard before.

6. Gaining Respect Takes Time

If the strength coach is slow to talk to you or slow to get to know you, it’s probably because previous interns were pure trash. Many interns are excited about their job for the first month but then start becoming lazy as soon as the motivation fades. Work hard, be eager to learn, do what you’re told, and the strength coaches will eventually deem you worthy of their time and effort. The same goes for dealing with athletes. Please don’t come in your first week and start telling a senior that they’re squatting wrong. They will quickly shut you out and stop responding to you. Instead, connect with the athletes first and establish a sense of trust before correcting them. They will be more receptive to your coaching if they know you are there to help them. Once they respect you, they will respect what you have to say.

7. Jump at Every Opportunity the Strength Coaches Give You

There will be occasions when the strength coaches need your assistance. When asked if you can help, your only answer is yes.

Are the strength coaches busy finishing with their previous teams and need you to run the next warm-up? You’re already starting athletes on their RPR wake-up drills.

Do the strength coaches need you to take some athletes through a conditioning circuit? You already have a stopwatch in hand.

Is a strength coach traveling with a team and needs you to lead another team by yourself the next morning? You already set your alarm extra early.

These are the exact moments as an intern that prepare you to be a future strength coach. Always say yes.

8. You Will Make Mistakes

Eventually, you will mess something up. Every intern does. How you respond to your mistake is what really counts. Learn from your mistakes and keep moving forward.

Forget part of the warm-up? Ask the strength coach to clarify, write it down, and memorize it.

Set up the wrong band for facepulls? Fix it and remember for next week.

Always learn from your mistakes because that will make you better. Additionally, if you make a much bigger mistake, such as waking up late and missing an entire morning lift, own up to it and tell the truth. Lying about it and saying you were in the hospital is a sure-fire way to lose that internship.

9. Read Everything You Can Get Your Hands On

Read as much as you can and read every day. Even if it’s just one or two articles on elitefts, at least you learned something that day. If you don’t like reading, start making it a habit. Pick a book and, at minimum, read one or two pages a night before you go to sleep. As far as books go, here are some of the basics that will give you a decent base from which to start:

Recommended Strength and Conditioning Books

- 5/3/1 by Jim Wendler

- Ultimate MMA Conditioning by Joel Jamison

- Strength: Barbell Training Essentials by Joe Defranco

- Speed Training Considerations for Non-Track Athletes by James Smith

- ConjugateU by Nate Harvey

- Designing Strength Training Programs and Facilities by Michael Boyle

- CEO Strength Coach by Ron McKeefery

10. Learn Good Coaching Cues

Once the strength coaches allow you to start coaching up athletes, you need to correct athletes with the minimum amount of words required to get the point across. No athlete wants to hear a five-minute step-by-step explanation straight out of a textbook on how to hip-hinge. Give them what they need to get started and guide them from there. For example, a squat should take about 10 seconds to teach. Maybe 15 seconds with corrections. “Wide feet, toes out, flat back, chest up, sit back then down, and knees out.” It’s really that simple. Once they know how to do the movement, use one- or two-word cues to correct deficiencies. The hard part is making sure the athlete understands and is responsive to that specific cue. Some athletes need to see the coaching cue performed, some need to feel the coaching cue, and others may need an entirely different cue. Work with the athlete to see which method works best for them.

11. High Schools are Very Different From Universities

Each facility has its own challenges and situational demands. For example, at Roland-Story High School, I was with athletes for two hours a day, four days a week. The amount of work we can have athletes do and the amount of time spent on individual facets of physical preparation (warm-up, running mechanics, jump training, weightlifting technique, conditioning, etc.,) is far greater than at Iowa State, where we might only see athletes for three hours each week. This was one of the main reasons why Roland-Story used the Olympic lifts, and Iowa State did not.

Another significant difference was the quality of equipment and space. University athletic departments have much larger budgets at their disposal and, as a result, better equipment and more space to work with. At Roland-Story, with six platforms and eight racks over a decade old in 1,700 square feet, it was not uncommon to have athletes spilling out into the hallway due to lack of space. In that situation, I was constantly moving around from group to group, making sure athletes were staying on track.

12. Get Hands-On Coaching Experience

If you intern with a Division 1 football team, you will unlikely be allowed to perform any hands-on coaching. From conversations I’ve had with other interns, the primary responsibility of football interns is to set up, tear down, and clean equipment. Even with Olympic sports, it could be months before coaches allow you to work with athletes individually. At the high school level, you can have upwards of 100 or more athletes come through the weight room in a single afternoon. They all need to be taught everything. You will see and correct hundreds upon hundreds of squats, RDLs, and push-ups. It is the ideal environment to improve your coaching ability.

13. Take 6-12 Weeks to Train Like an Athlete

Whether you're a powerlifter, bodybuilder, or CrossFitter, it is important to understand exactly what your athletes are going through. Write a 10-week Triphasic program or a 10-week Tier program based around baseball or basketball. Program in jumps, sprints, and conditioning. Doing so gives insight into how each workout affects your athletes in the short and long terms. If an athlete comes in during the seventh week of a Triphasic program complaining about how sluggish and zombie-like they feel, you’ll know exactly how they feel because you’ve been there before and can reassure them that it is only temporary. This gives you more credibility than a string of letters behind your name.

14. It’s Okay to Disagree

During your internship, you will be exposed to various methods of training athletes. You will find out what you do or don’t like and what does or does not work. Some strength coaches are loud, hype-man, “bring the juice every day” -style coaches. This isn’t my style. It’s not who I am as a person or as a coach. Pretending to be someone that I am not would come off as inauthentic and fake. And that’s okay. You don’t have to agree with everything that the strength coaches do but have your reason for why and (if asked) offer a solution.

For example, I am not a fan of behind the head band pull-aparts, which were occasionally included in programs at Iowa State. I feel that the movement itself is not effective at stimulating the mid and lower traps, plus athletes have a hard time performing them properly, let alone even feeling the movement in their mid-lower traps. Alternatively, I would prefer to program in band facepulls with a high attachment point at the top of a rack. The band's angle would force the athlete to use their mid-lower traps to both retract and depress the scapula while simultaneously engaging other upper back musculature.

If you disagree on something, you have two options. You can keep it to yourself or ask the strength coach about it. If it is the style of coaching, obviously keep that to yourself and make a mental note that you don’t like to coach that way. Is it a method or a movement, such as in the example above? If so, I recommend asking about it. If you decide to ask the strength coaches about it, be respectful and see the issue from their perspective. Try to understand why they want athletes to perform certain movements or why they want to perform those movements with a certain technique. The disagreement might stem from your lack of knowledge, not theirs.

15. Develop a Coaching Philosophy

A coaching philosophy is a set of guidelines from which you develop your program. As an intern, it is okay not to have one fully laid out. Start piecing together the foundation of your overall program. Don’t ditch your core philosophy for the latest and greatest fitness trend. Still, constantly learn and try new things. If a new concept, method, exercise, stretch, or modality works, then add it into your toolbox. If it doesn’t work, learn from it, throw it in the trash, and move on. At least you’re not far off course because you stuck with your core philosophy.

For example, if a young coach who uses linear periodization begins reading about conjugate periodization, they probably shouldn’t ditch everything they were doing and immediately begin programming in max effort and dynamic effort days. This isn’t to say that conjugate periodization is bad. Conversly, I believe conjugate periodization is probably one of the best ways to train athletes. Improperly adopting a method without a deep enough knowledge base, prior testing, and self-application is a recipe for disaster. Take the time to truly learn and apply a method before throwing it out because you didn’t implement it properly.

16. Start Paying More Attention

In the beginning, you should be able to distinguish between different movements and what basic technique should look like i.e., squat versus a hip hinge, catching a clean, basic push-up position, etc. Over time, as you start accumulating more hours at your internship, you should develop an eye for the smaller details. You will start to notice little errors like ankle pronation during squatting, excessive shoulder rotation during presses, and scapular protraction during pulling movements. Anyone can tell an athlete to squat lower, but can you identify and solve the true issue that’s preventing them from reaching depth? Start looking for these mistakes and coach up the athletes.

17. Your Technique Probably Sucks

Two years from now, you're going to look back on your squat form and realize how terrible it is. Always continue to learn more about technique and continually refine your own. This is especially true if you have been lifting for less than five years. Going back to the point addressed above, start looking at the details. When I originally started squatting, my toes were turned too far out, and my hips were always shooting up out of the hole first. Also, most of my deadlifts were finished with excessive lumbar extension, and I was over-tucking my elbows in the bench press. Even if you think your technique is good, ask the strength coaches what needs to be improved. You’ll be surprised how much work you need.

18. Connect with Your Fellow Interns

Connecting with your fellow interns doesn’t mean that you need to become best friends with them. Instead, get to know and interact with them. This is one of the few instances where someone has very similar interests as you, allowing you to geek out about strength and conditioning subject matter that your other friends don’t really care about. Discussing box squatting, Olympic lifting, using straps on an axle bar, or super high box jumps with someone who has a roughly equal level of knowledge, yet opposite viewpoint can be enjoyable.

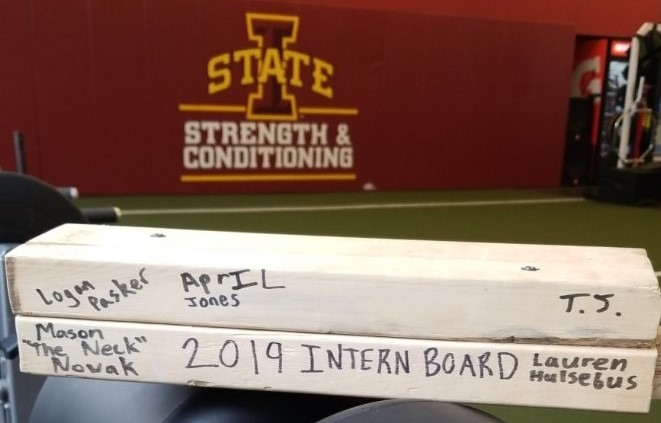

After the first two years of being the only intern at Iowa State, it was nice to finally have some peers to work with. All of us together resulted in a delightful blend of personality and insight. Luckily in September of 2019, most of us were able to come back one last time and reminisce on our favorite memories. I made all of us sign a two-board (even though they thought it was lame). I prefer to think of it as sentimental.

Bonus!

6 Quick Tips

- Barbells are not always the best piece of equipment for training athletes; specialty bars might be better.

- Create an exercise progression-regression chart to get athletes from where they are to where you want them to be.

- “1, 2, Superman!” is an excellent cue for approach jumps.

- Never attach chains in a straight line from the bar. Use a small feeder chain instead. For deadlifts and floor press, drape the chain over the bar.

- “Speed” ladders suck for developing speed but are great for waking up athletes at 6 AM.

- If speed work doesn’t look fast, then it’s not speed work. Take some weight off the bar. Same thing goes for plyometrics. Speed, speed, speed!

Follow these tips, and you will be years ahead of other interns.

Logan Pasker is a graduate assistant–strength and conditioning coach at the University of Dubuque. He earned his bachelor of science in kinesiology and health from Iowa State University in 2019. During undergrad, he interned with Olympic sports at Iowa State University and Roland-Story High School. He can be reached at loganpasker@gmail.com.