The big DE, the dynamic effort method, Speeeeeed work, DEM! If you’re a reader of this site, I’m sure you’re familiar with such a method, but can you use this method with athletes? Powerlifters aren’t athletes—let’s be honest. Quick refresher:

The DEM was introduced to us by Vladimir Zatsiorsky and made popular by Louie Simmons. When describing DE work to a powerlifter, we typically describe it as lifting a non/sub-maximal load with the greatest speed possible (focusing on compensatory acceleration). In other words, apply as much force as possible into the barbell during the concentric phase of the lift.

The definition Zatsiorsky gave us was: lifting a submaximal load as fast as you can. That’s it. He doesn’t once say it should be used only with the squat, bench, or deadlift. The reason Louie did speed work with the three main movements was that he trained powerlifters and their sport was powerlifting. The reason they performed this method is they needed to increase their bar speed…for their sport.

Remember, the sole purpose of the DEM is to improve the rate of force development and explosive strength. I interpret that as the DEM can be used to make our athletes more powerful. As coaches of athletes, our goal is to prepare them for their sport, and one of our goals is to always make them powerful. How can we incorporate the DEM with our athletes? By running, jumping, and throwing. Why not do speed work with the movements that they will see in their sport? Teach them to apply as much force as possible into the ground as opposed to the barbell.

When developing a training program for athletes, you have to look at what will give you the best results in the least amount of time and won't require too much time spent teaching the movements. It isn't always about one movement being better than another. It’s what’s better for you and your program. You have to factor in aspects like time management, athlete experience level, and learning ability. For example, a lot of strength coaches love the Olympic lifts because they "teach speed, explosiveness, and triple extension." Which is great and all, but just because you’re doing “Olympic lifts” doesn’t mean they are actually doing what you say they are doing. I’d be willing to bet that a large number of the athletes doing these cleans with submaximal loads aren't reaching triple extension at all. Not to mention that any lift can be done explosively. As long as the lift is being done with submaximal weights in an explosive manner, that’s what counts. Your athletes’ intent should always be to move the bar explosively, DEM or not. For more information on teaching Olympic lifts, read this.

I’m not saying that barbell DEM work doesn’t work; it does work, but I feel that barbell-based dynamic effort work should be saved for your athletes who have mastered the lifts in which you’ll use that method. As Mark Watts says, “Most athletes aren't even strong enough or efficient enough to produce enough force to elicit a training effect with powerlifting style dynamic work.” Take the time to teach them how to do the movements correctly before you add other variables, such as bands and chains. If they can’t squat for shit, why would you add short rest periods, chains, and bands on the bar? If you’re interested in using the DEM and the barbell lifts with beginner athletes, check out this article by Nate Harvey. He provides a great case for using it.

My biggest suggestion to you is to study it, implement it, see what happens, and form your own opinions. Nobody is right or wrong. At the end of the day, we are all trying to achieve the same thing.

Before we get into the actual movements, I want to touch on the topic of the ready position. Some refer to this position as an “athletic base position,” but I feel that the ready position is a better name to describe it, as all athletes need to be ready to move out of. Hence the ready position. You as a coach should be incorporating ready position work into all of your warm-ups and carrying them over into these drills. This is one of the most fundamental and important positions in sports. If your athletes cannot own and maintain this position, then do your job and get them there so that every time they are in this position, it’s perfect. Take pride in getting your athletes to master this position.

Something important to keep in mind here as I give programming considerations is that if it looks like shit, it is shit. If it looks slow, it is slow. The point of this is to increase force production. So, even if it’s written on the program, use good judgement.

Throws

I love throws. They teach triple extension quicker than Olympic lifts do (I’m a big proponent of Olympic lifting, so relax). Medball throws are much more cost effective and less time consuming than Olympic lifts are. They are easier on the joints. The variations are endless, as they allow the athletes to perform them in multiple planes. They are also much easier to learn and are fun to do because they get the athletes to compete, as they can instantly measure how far they throw. Just make sure that the athletes are throwing as hard and as fast as possible, just like with speed work. Otherwise, if the ball is too heavy, they are merely doing strength work. No need to go over 10-15 pounds on your throws. Especially on rotational throws, I don’t ever go over 10 pounds.

Programming

For throws, I’ve used Prilepin’s chart. I’ve used a goal of 30-50 throws a session using 3-6 different types of throws. I’m not married to one or the other; I guess it would depend on where you’re at in your athletes’ season, as they can be used to develop capacity where the athletes have incomplete rest or power where they need complete rest. Sometimes I’ll allocate 10 minutes for throws.

Example using Prilepin’s chart:

70-79% range: your optimal reps are 18, but you can go as high as 24 throws or as low as 12. You want no more than six throws per set but no less than three.

So, set and rep schemes could look like this:

- 4x3

- 2x6

- 4x4

- 6x3

- 5x3

Example using time:

Say we have 10 minutes, 18 athletes. I would group the athletes accordingly. You can do this in one of a few ways. The way I would set it up is athlete one is doing throws, athlete two is doing some type of pre-hab, and athlete three is resting/coaching. Get through as many times as possible in 10 minutes.

Another way is to put them in groups of six: three on one end and three on the other. They throw the ball and then follow their throws to the sides on which they threw it. After five throws, everybody does some type of pre-hab movement.

Jumps

Just about every sport requires an athlete to jump. Why not train it? You have four planes in which you can train your jumps: vertical, linear, lateral, and rotation. Then, with your more advanced athletes, you can combine multiple planes. Different types of jumps include standing, seated, kneeling, weighted variations, hurdle variations, jumping onto boxes, or jumping over boxes. The possibilities are endless. Whenever possible, ensure that your athletes are always sticking their landings. This does a few things; first, it teaches them how to absorb force in a closed environment so that the pattern is being neurologically engrained. Also, learning how to land effectively allows the athletes to prepare for the next movement.

With regard to box jumps, I get it—it’s cool to have an athlete jump on a high box, but watch how the athlete actually lands. Usually in a low squat position and a rounded back. What’s this actually teaching? Keep it athletic.

Programming

For jumps, I’ve used Prilepin’s chart, but over the years, I’ve found that you can look at the chart in two different ways.

First way:

The athlete has a 36” max box jump. Here is how I would program the athlete's jump training over three weeks:

- Week 1: 75% of 36” for six sets of three jumps

- Week 2: 85% of 36” for five sets of three jumps

- Week 3: 95% of 36” for three sets of two jumps

But with regard to my previous statement about box jump height, I don’t care for this format.

Second way (the way I prefer):

You base it on the level of difficulty. The more difficult/higher intensity the movement, the lower the total volume. A box jump is an easy movement, so that would fall in the 70-79% set and rep scheme. Meanwhile, a box jump to a depth drop to a bound to a vertical jump has a higher degree of difficulty, so it would fall in the 90%> set and rep scheme. If we use the box jump to a depth drop to a broad jump to a vertical jump, this would constitute as one rep.

I highly recommend that you pick up Coaches Guide to Jump Training by Bobby Smith and Adam Feit. This is an extremely valuable resource that every coach should have.

Some coaches follow a contact guideline, and some national associations advocate this. Their “advanced” athletes get up to 150 contacts per session. Personally, I don’t have the time for 150 contacts a session; most athletes don’t have the attention span for 150 contacts per session, and have you ever tried doing a CNS-intensive thing like jumping and doing 150 contacts a session? Feel like that’s asking for injury, isn’t it? Quality not quantity!

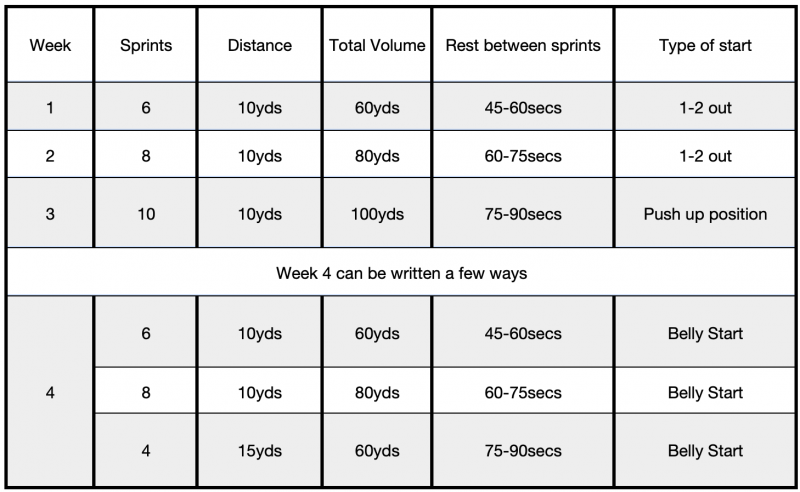

Sprints

Sprints are very CNS intensive and extremely dynamic. Your options, again, are endless. Try various start positions and distances; even incorporating jumps with your more advanced athletes. Make sure that sprints are done at the beginning of the workout and that proper rest is given. In a team setting, 30 seconds of rest for one second of sprinting should be enough (more knowledge I gained from talking to Mark Watts). I know that a lot of top sprint coaches prefer a few minutes per second of running, but most of the time, we don’t have that luxury during our training sessions to devote that duration of time to recovery. BUT when in doubt, allow for full recovery. We aren’t training the aerobic system (that’s a different article). I'd rather do fewer sprints with full recovery than more sprints with inadequate recovery. Pay attention to volume when it comes to programming along stressors in your athlete’s life.

Programming

I approach sprint programming a little differently than I do throws and jumps. I do it based on total volume/yardage. For every athlete I have, we start with 10 yards. If your athlete is de-conditioned or hasn’t done much physical activity in a while, once you get over 15 yards, you will start to see hamstring injuries. When in doubt, do 10 yards or fewer for the first 3-4 weeks. Remember to do 30 seconds of rest for each second at the least.

Volume should slowly increase. You should decrease volume when you introduce a new start variation. Also, programming would look different based on which energy system we are targeting.

Conclusion

This is just a different way to look at the concept of dynamic effort training with your athletes. I challenge you to look at things differently and to question everything. Although the concept of getting athletes more powerful is simple in theory, we are all in different situations, and we have to figure out what works best for our athletes. What works for one coach doesn’t necessarily mean it will work for you. What are some ways you’ve approached getting your athletes more powerful?

Image credit: tarczas © 123rf.com