Hotdog water bubbled on the stove, steam smelling like baseball and summertime clung to the kitchen walls like sweat on a glass of sweet iced tea. I was 8. My dad, elbows on the counter, bent at the waist, alternately wiggled his knees while he drank instant coffee that always stained his teeth and breath, read the weekend paper and waited for lunch to cook. I was already picking bits of a first helping from my back teeth wondering aloud if I could have more.

“Well you’re fat and happy, Emma, but your brothers haven’t had any yet! Just wait,” he’d laughed.

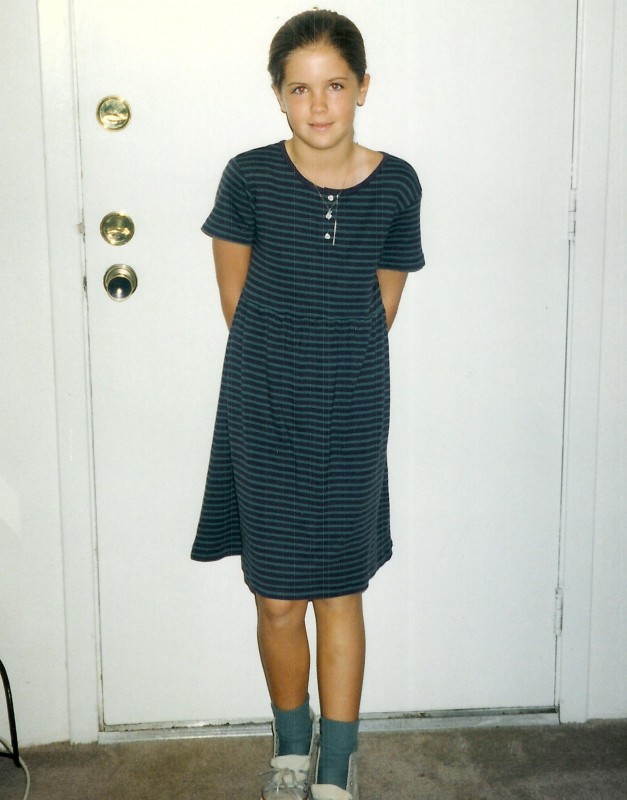

Suddenly I wasn’t hungry anymore. I wasn’t fat either – my brothers and I were all tall and athletic, a bit boney in the knees – but my dad just called me it. He hadn’t, really. It’s not what he meant. But I was 8 and a girl and I heard it. Sulking to the back of the walk-in closet off my room in the back of our first floor apartment, I sat on the floor and held up my Barbie dolls, squeezing their thighs together as hard as I could, convincing myself women’s legs were supposed to touch in the middle because mine did and if I tried hard enough so did hers.

*

“Pull your pants down and spread your feet. Oh good, you don’t have a puffy pussy.”

“Pull your shirt up I wanna see if I could ride my Tech Deck between em.”

“Ross has a crush on his sister,” because he was 12 and I was 13 and he got mad when all his friends chased his sister around the trampoline trying to shove their hands down her pants and pull her clothes off.

“I want your virginity for my birthday.”

“She didn’t know how to suck dick at first, but I taught her and she got better,” jealousy and rage in the form of an ex boyfriend yelled angrily from the other side of the door, behind which his best friend was pulling me on to his lap to keep drinking too much.

And other things teenage boys say to teenage girls that make them hyper-aware of their bodies, and begin to see ourselves as we think others do: conditionally useful, of “right” and “wrong” types, sources of shame and embarrassment, up for grabs.

*

I could only take labored, shallow breaths, overwhelmingly crushed by the fear of nothing at all and absolutely everything at once. I couldn’t move, or close or open my eyes, or will any muscle in my body to act on the most desperate command. After 30 minutes, maybe more, flat on my back on the stiff red couch in the middle of the living room in my second floor apartment, I slowly defrosted from inexplicable paralysis, drug one heavy hand to the corner of the couch, unsure how I was finally able to will it to move, grabbed my phone and called my mom.

“I think I just had a panic attack.”

I was 24. My daughter was 2. I went to one doctor for talking and another for slips of paper to exchange at the pharmacy for Lexapro or maybe Prozac. Xanax for emergencies that made me fall asleep at my desk.

*

It’s an indescribable pride a woman of a certain mental framework experiences the first time she lays on the ground and counts her own ribs, tracing the protrusions from her chest down, grabbing her own hipbones, so sharp the elastic waistband of her underwear spans them like a tension bridge without touching her belly so concave you could ride a Tech Deck on it.

I hadn’t eaten in a couple years and had taken up running nearly 50 miles a week. Stomach paining in in the success of hunger. Keep going, skip food, go to bed hungry, wake up tight. My clothes were all too big. Everyone noticed how good I looked and how fit I was. My knees ached constantly from the miles I put them through. Some days I couldn’t walk at all from the insertional Achilles tendinitis – I perched my heels on buckets of ice under my desk to dull the pain. I still ran every day but popped 2 Vicodin from an old dental surgery to get through it. My mom worried. I ran up and down the stairwells in the parking garage on my lunch breaks. I wouldn’t even drink water I wanted my intake at absolute zero. Eat nothing, drink nothing, don’t take up space. I was 26.

I only almost passed out driving home from the track twice. Only actually did once. But if I ran every single day no matter what, I wouldn’t find myself frozen alone on the stiff red couch anymore, and I didn’t have to see the talk doctor anymore or take pills that made me fall asleep at my desk.

*

“You’re a 27-year-old girl with a 17-year-old body!”

I refused to step foot in the public gym space, where men poured sweat in the squat racks and women slumped over the stairmills. I stayed where it was shadowy and dark and the equipment was limited. I worked my way around the room, hammering each machine enough to make it hurt, then going back for more, then doing it again, because when you’re too afraid to step foot outside of the smoked glass women-only room of the local commercial gym, it’s what you do. And when you are indescribably ashamed of yourself and embarrassed by inexperience, you hurt in hiding. When the salsa music faded after Zumba and the grinning buzzing kickboxing classes filed out, I crept into the darkened group class studio and set up my phone with at-home workout videos to do alone. No one looking. Lights stayed off. It was safe there, too, with a door in the back connected to the women’s gym, connected to the women’s locker room, which let out near the front desk and the illuminated red exit sign.

The parking lot, though, was unsheltered. Walking to my car, 5-year-olds hand in mine, looking like a teenager though nearly 30 years old, Eric called across, attracting attention including but not limited to my own. My face burned hot and red, fingertips tingling in embarrassment.

He told me, “Come back tomorrow at 5:15 you train with us now.” They would “get me together.”

He had an unconvincing snarl he would unconvincingly say “drives the ladies in Twinsburg wild.”

He took me to my first powerlifting meet.

“You’ll do more than anyone in this room if you quit fucking around and eat something,” and the kindness in his eyes showed when he smiled.

*

“I’m so pathetic I can’t even make myself puke.”

Angrily smearing tears across my swollen cheeks with the back of my hand – it and the plastic handle of my toothbrush covered in half an hour of already failed attempts – I glared down at the empty toilet. I was a bodybuilder now. And a binge eater. I could eat nothing or I could eat everything, there was no in between. Hunger is success, pain is progress, misery is accomplishment and the structure was calming. I hated myself. We all did.

I’d been training twice a day every day for two years, through two surgeries, it would take another two to unlearn the food guilt; To not have to “earn” calories; To not be disappointed when the scale didn’t go down every single morning; To not destroy my sleep, body vibrating at my desk with twitching fingers and odd heart rhythms from clenbuterol, or lie cramping on the bathroom floor from enemas so I could send my coach a “positive” (lighter) check-in; To not want to restrict, throw up or chew-and-spit. To this day I’d still rather be hungry than full. Bodybuilding is a foul sport and hardly anyone is good at it. Many women of a certain mental framework find a haven in it to normalize disordered eating and enable or confirm their own body issues because now a line of glaring judges could officially agree with them while Instagram lauded their “mental fortitude” and “drive.” We were all on the cliff’s edge, ready to crumble. A rose by any other name still pricks.

Bodybuilding coaches to insecure female athletes can sound a lot like teenage boys on trampolines much of the time, chasing us around, trying to shove their hands down our pants and pull our clothes off, teaching us to measure our self worth in units of attention. Female bodybuilders often see themselves as teenage girls do: through the eyes of men, conditionally useful, of a “right” or “wrong” type, a source of shame and embarrassment, up for grabs.

It took 20 years to unlearn that. It took powerlifting.

*

It reeks. The putrid smell of sweat, urine and testosterone clings to the walls like sweat on a glass of sweet iced tea.

“And the heavyweight winner is, Emma Jarman!”

My face burned hot and red, fingertips tingled. “Heavyweight Emma.” Fat. Fat and happy. But grinning and half-drunk by now on adrenaline and whiskey I shuffled back to the platform and clumsily arranged the oversized World Champion belt around my bare waist, fumbling the small paper check and flinging my free arm around the sweet little southern girl I’d only just met with the big voice that convinces us strong girls are possible. She’s the strongest woman in the world today, she showed us. The flash bulbs and spotlights are near blinding. I let the corners of my mouth reach for my ears, throw my head back in uninhibited laughter. Hug. Celebrate. Happy.

The excitement mellows quickly, the room goes dim and the crowd filters out of the sweat room onto the snowy city street on the other side of the door. I was 32, it was well past my bedtime. Crossing my legs in the hallway under the escalator, I grabbed my phone and called my mom.

“I think I’m a powerlifter now.”

*

“I train for performance, the body is a fortunate side effect,” is the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to convince myself of. “Food is fuel, not fun,” comes in a close second. I’m usually telling the truth when I say these things, sometimes lying.

I’ve recovered from the trauma of competitive bodybuilding, the trauma of being a young girl, a teenage girl, a 20-something girl, I think, as well as I ever will.

I am 33. I have multiple pro totals, am a top ranked powerlifter, competitive on international platforms, have won cash prizes and formed productive, supportive, healthy, persevering relationships with women in this community across the country that I am most proud of – notably with myself. I don’t hate myself. I don’t agonize over how I look even if it’s not always a source of comfort. I don’t prioritize aesthetic. I admire my own capability and it’s what I admire now too in others. I eat the extra hotdog and I haven’t run a mile in years.

I am a powerlifter.

Still, I am a female powerlifter.

I weigh all my food daily. I weigh myself every morning. I am secretly pleased when the scale number has dropped, even if I’m not trying to lose weight and even if logically, I know it will harm my performance. I don’t feel like I belong.

I experience food guilt and occasional binge eating.

I struggle to accept weight fluctuations.

I want to be “strong not skinny.” I secretly want to be strong and skinny, but I can keep that voice quiet these days.

I tell myself and others my physique is a fortunate side-effect, only because I’m lucky enough to have ended up with something I’m happy with – something that’s relatively socially acceptable. If training for strength didn’t still keep people questioning whether I was a bodybuilder or powerlifter, I don’t know if I’d be so readily tolerant.

I wish powerlifting existed when I was a teenager as it does now for young girls. I wish I could have learned how capable I could be while we were all deciding what the point of girls was. I was a swimmer all my life and a good one, but it didn’t outweigh one single body issue. I wish I could have learned food was fuel when I was 15, not that it was a tool I could use to punish and manipulate myself and my anxieties in my 20s. I wish I could have learned unconditional confidence.

Powerlifting unlearned a lot of internally focused negativity and taught me I am useful, every type – even mine – is the right type, my body is a source of pride and accomplishment and no one can touch it. I hope the next rounds of girls find their “powerlifting” sooner than adulthood because in my generation of us, we could have used it.

Header image credit: © Jamie Miller Productions

Emma Jarman is a Cleveland, Ohio-based mother of one, amateur baker and writer. In her downtime, she works full time in marketing. Emma’s athletic background is in swimming and running with a short stint as a figure competitor. She entered the powerlifting community in 2015 and has since earned multiple pro totals and a top 10 ranking in the 181-pound weight class.

5 Comments