One thing I’ve noticed working with coaches over the last 10 years is that many of you are afraid of programming because you simply don’t know how to program. No one taught you, and the task of learning it yourself seems daunting. Building on my last series on programming for athletic development, in this next series I’m going to teach you how to write those programs. Think of this series as a class: I will be giving you information and assignments to help you build and develop the tools and systems needed to write effective programs for your athletes. Don’t worry, you’ll have a month between each “lecture.” I know you’re busy.

The problem is that most of us tend to think of programming as just sets and reps, but it’s bigger than that. We can’t just throw random exercises along with random set and rep schemes on a piece of paper haphazardly and just hope for the best. You need to view programming and periodization of your athlete as a long and slow process. It’s like good barbecue: you can’t rush it. Be patient when it comes to programming and training your athletes. Also, you as a coach need to be patient as you learn this process and improve. You, too, are a delicious BBQ pork shoulder.

Introduction

Here's a scenario you've likely found yourself in: Sitting there at your desk, tabs open all along the top of your web browser. Books scattered about. Highlighters, sticky notes, and a stack of notebooks from your internship. Trying to figure out what the plan is for your athletes this coming season but being unsure where to start. Staring at this mess in front of you. Knowing the answer is in their somewhere.

WATCH: The Strength Coach Development Center — Overhead Press Progression

We are our own worst enemies when it comes to programming. It has to be perfect, yet all we do is overthink it. We panic. So what do we do next? Look to copy those that have come before us. Quickly Google search "programming for girls softball in-season.” (By the way, if you’re looking for that program, Nick Showman wrote a pretty solid article on it here.) But how do you know those programs even work? Do you have the before-and-after results? The only way to know for sure if your program works is to write one, implement it, and see how it goes. Obviously, I’m oversimplifying it, but at the end of the day, it’s that simple. This doesn’t mean it’s easy. One of the most important parts of our profession is going through trial and error in everything we do.

I get it, you just want to coach. I mean, it’s in your title. And a lot of time goes into writing a program — that’s why it’s much easier to just copy somebody else. How do you get better if that’s your approach, though?

Programming and periodization are the foundation for what we do. They are the blueprints. My goal is to present you with tools you can use to make programming easier and more systematic. I will divide all articles into two sections. The first will be more of a science-based section. Everything you read on programming is very science-based and boring. I will admit I felt stupid at times reading research papers on periodization and programming, and I feel that this whole process is just overcomplicated when it doesn’t have to be. The science part is important but I promise I will do my best to present it in a manner that is easy to digest and retain so you don’t fall asleep while reading it. The second section of each article will be about application. At the end of the second section, there will be an assignment for you to do. This assignment is important, as it’s literally giving you the tools you need to write your programs. Make sure you do it.

Section I: Programming vs. Periodization

Many of us confuse periodization and programming. I mean, I do — they both start with the letter P. When it comes to things that are similar yet different, the best way to approach it is to come up with creative ways to understand them. Periodization has the word "period" in it. Those periods are merely subdivisions in our athlete's training. Each period has a micro or small goal that is usually one of the following: strength, power, speed, endurance, or hypertrophy. Programming, on the other hands, is the act of creating a plan to achieve those goals.

Our overall big goals with periodization and programming are:

- Maximize specific training adaptations (micro goals)

- Elevate our athlete's performance at appropriate times

- Manage fatigue and reduce overtraining

How we achieve these goals is through variation, by manipulating training variables. These training variables include:

- Exercise Choice: Choosing an exercise that will lead your athletes towards their goals. If you pick an exercise it should be for a reason, not because it looks cute.

- Exercise Order: Large muscle groups and multi-joint exercises first, small muscle groups and single-joint exercises after. Additionally, your highly technical exercises should be done first in the training session.

- Volume: The sets and reps performed in the training session.

- Intensity: The amount of resistance used during a training session, usually represented as a percentage of the athlete's one-rep max.

- Rest Periods: Dictated by the goal of the program. The length can influence everything from hormonal response to metabolic responses. It will also dictate what and how much you can do within a given training session.

Periodization Principles

Now that we have simplified things a little bit, let's take a deeper look at it. Periodization, at its core, is based on three principals that will dictate our programming, remembered as OSV:

- Overload Principal: Constantly applying the appropriate stimulus at the appropriate time in order to achieve a psychological, physiological, or physical adaptation.

- Specificity Principal: Degree of similarity between the performance and training exercise.

- Variation Principal: How we manipulate the overload and specificity principles. We manipulate this through the training principals previously mentioned.

The overall goal of any program is to take advantage of the body’s ability to adapt to stress and elicit a specific training response. The training response we are looking for in athletes is to create the right adaptations at the right time to ensure success in their sport. The reason we have to have a plan is that the body is very stubborn but very adaptive. It prefers to maintain homeostasis at all times, so when we train we cause a disruption to our homeostasis and our body must fight to get back to homeostasis.

Benjamin Rosenblatt of the English Institute of Sport, states "Periodization is the strategic planning and monitoring of training in order to facilitate the right adaptations at the right time to lead to success on whatever your field of play is." So essentially, we are manipulating our training stress to produce the desired outcome.

Now, continual stress and disruption over time leads to adaptation to that stress. If we design a program with proper volume and intensity, along with recovery over a period of time, our athletes will become much more prepared for their sport. Keep in mind, though, if volume, intensity, and frequency are too high or low and recovery isn’t sufficient, we may see no effect or even possibly a negative effect.

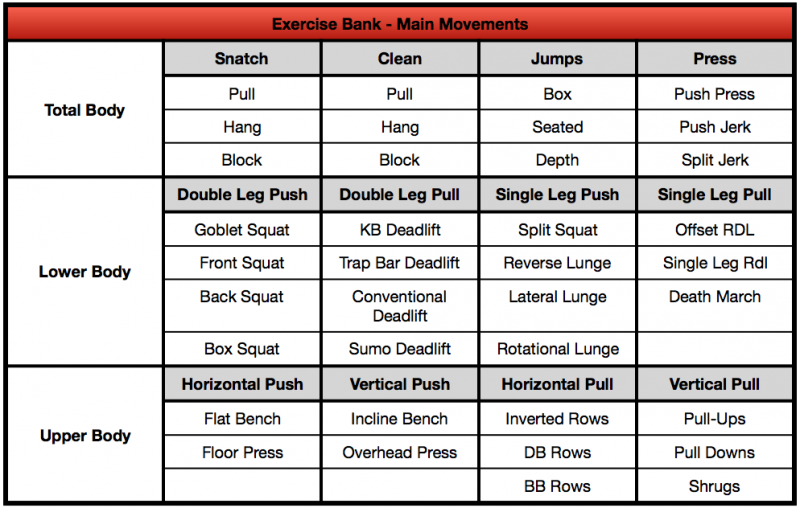

Section II: Building an Exercise Bank

One thing Joe Kenn and Mark Watts taught me is that you need to develop an exercise bank. This bank includes exercises that you are proficient in coaching and performing. I am a big proponent of walking the walk. I’m not saying that you need to squat 600 pounds, but you should know what it’s like to squat under a heavy load, especially if you are teaching athletes how to squat under heavy load. I wouldn’t take my car to somebody who watched a YouTube video on how to replace an alternator but had never actually replaced an alternator. The same goes for lifting. The more you can relate to your athletes, the more they will buy into what you’re selling. If you're not proficient in teaching or performing Olympic movements then don’t do them. It's that simple. The exercises in your bank should be ones you are confident in coaching. That includes the proper progressions and regressions.

There are various ways to organize it, but separating it into total body, lower body, and upper body lifts will be a good start for most of you. Over the course of your career, you will modify it. I know based on Joe's The Coach's Strength Training Playbook, his exercise bank is a little more diverse and detailed. When choosing your exercises, you need to make sure that they fit into your overall training philosophy. If you don't believe in the box squat, why would you use it?

Assignment

Design and develop your own exercise bank.

My First Exercise Bank

This was the first exercise bank that I developed with the help of Mark when I first got into coaching. These are the exercises I preferred as a coach when I got started, and the ones that I actually enjoyed coaching and performing. The order I have them in is where I actually started my athletes and progressed from there. Over the past 10 years it has evolved and become more in-depth, but as a new coach, it got the job done.