Many of us are currently going through off-season preparations in order for to prepare our athletes in the highest order. At the high school level, there are many factors that may cause you to deviate from your master plan on a daily, monthly, or annual basis. I've written previously about the importance of specializing for certain athletes in high school sports and how to begin that process. However, what is one to do if you work in an environment with incompetent coaching that doesn't factor in the daily workload being placed on your athletes? The answer is simple—you must adapt and adjust your intelligently designed plan to fit the needs of your athletes.

The Problem

Most of us have some of our best players’ running track presently. Not many of us have track coaches who know how to properly develop a host of qualities that enhances what we do in correlation as football coaches. Some of the things that you know how to instruct may be getting destroyed right now on a daily basis. Those could be classified as proper running mechanics, acceleration as a skill, alactic power development and reactive/elastic qualities as well as avoiding the anaerobic glycolysis realm of bioenergetics during practice and maintaining muscle suppleness.

How do you address these issues without completely undermining the entire athletics program? Outside of developing a relationship with the track coach and trying to explain to him that what he is actually doing is destroying the athlete, you must change your plan on an individualized basis so that you don't overload that athlete and predispose him to a host of injuries.

The Solution

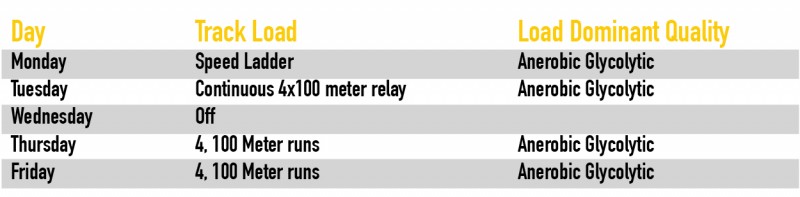

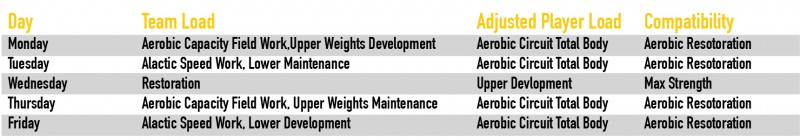

As you progress through your weekly and monthly loads leading up to spring practice, it is imperative that you form a compatibility with the load that you demand from your players, if applicable, with other loads that you can't control. It would be negligent to disregard the other loads that take place out of your control and simply demand that the athlete complete everything from both parties simply because of pride. The following weekly template is an example of what I did with one of my top wide receivers who was a member of the school’s 4 X 100 meter relay team.

For those of you unfamiliar with some things that some individuals do at the high school level in attempt to develop “speed,” I'll provide the following real life examples:

- Speed ladder: Each athlete will run a 100/200/300/400 and then progress backward with one minute between each rep. The load dominant quality is the anaerobic glycolytic mechanism.

- Continuous 4 X 100: Each athlete will continually run 100 meters at a submaximal pace. There isn't any time associated with the submaximal pace, so it is all guess work. Because I err on the side of caution, the load dominant quality is the anaerobic glycolytic mechanism, as there aren't any set number of reps and it's all time based (i.e. six minutes continuous 4 X 100).

- Four 100-meter runs: This is a single day where the athletes run four 100-meter sprints in practice with 60 seconds rest in between. The load dominant quality is the anaerobic glycolytic mechanism.

As you can see from the examples above, a large majority of the work is geared in the lactic zone. Are we able to assess this via lactate analysis? No, but I constantly ask my athletes how they feel after running a particular load for the day, and the dominate answer is “high amounts of burning in their legs.” So it's easy to gauge exactly what type of training occurred that day.

The above table is an example of one week of training during the middle of track season. The biggest problem is that at our school, we have, on average, one track meet a week. So I have to continually monitor on a weekly basis exactly what occurs so that I don't overload and injure the athletes who have the highest outputs on our team. To provide some context in regards to outputs, our primary 100-meter athletes run between 10.8 and 11.4 FAT.

The key in the whole situation is that you, as the coach, don't let your ego get in the way and force your training load on to your athletes who possess the highest output. It doesn't matter during track season how much the athlete can squat because the stimulus that he's receiving, albeit a lactic one in most cases, can be counteracted by stress or loads that you provide.

The last table that I'll provide is an instance in which our top running back, who is also on the 4 X 100 meter team, was completely mismanaged and ran into the ground prior to the state championships. As you can imagine, he had a hamstring pull in the first preliminaries of the finals. At that point, he came back to me the following day and I utilized two valuable manuals—Gerard Mach’s Sprints and Hurdles manual and James Smith’s Applied Sprint Training Manual.

In Mach’s manual, he provides a ten-day protocol for hamstring strains. You can manipulate the volumes of linear running in order to be more specific to the positional requirements of the football position that your player plays. James’s manual has the sequence of events from an active recovery standpoint along with power speed drills delineating whether the strain was distal or proximal. The key when utilizing these manuals is constant communication between yourself and the athlete you're working with.

Looking at the table, there are some things I'll discuss in order to paint a clear picture. The heat/Aspercreme wrap was utilized via the Applied Sprint Training manual by James Smith. I also referenced that manual for the progression of power-speed drills from stairs to flat land. The tempo times are based off 60 percent of his maximum output at said distances. I wanted to be conservative rather than jump to 75 percent from the get go, as day one was directly after the track state championships on May 2.

At the time of this writing, he has integrated himself to approximately 90 percent of required activities, and there aren't any negative consequences of the work that he performed during those ten days.

The context of the provided examples of this article could be referenced for any sport that your athletes may participate in outside of football. However, the key to the whole situation is that we must be mindful as coaches of what takes place in other coaches’ practices so that we don't overload our athletes, especially the ones who are at the top of the pecking order come Friday night.

References

- Mach G (1980) Sprints and Hurdles. Canadian Track and Field Association, pg 61. Availability limited.

- Smith James (2014) Applied Sprint Training Manual.