While I was going to do another column of pot-stirring on various other topics, the topic of belly breathing has been stewing for a long time in my head, and it's time this pot has been stirred. It needed its own column because I think it’s extremely important.

Please read the entire article before you decide to make a comment. I have a logical and intelligent discussion on the grounds that you read the article in its entirety.

RECENT: Stirring the Pot, Volume 1

Intro

First off, breathing isn’t bracing. Bracing is a whole different discussion, which I’m not going to talk about today, I promise though, if you’re able to get breathing mechanics down, bracing will be much easier.

When I’m talking breathing I’m talking about respiration — the act of moving oxygen from the outside environment to our cells and tissues and the transport of carbon dioxide out.

What prompted this article was working with clients over the past 10 years and not getting what I was looking for as far as breathing mechanics and coaches saying to put your hands on your belly and breathe into your belly.

While the intent or the cue is in the right place, it’s simply not right. Telling people to breathe into their belly is wrong from a mechanics standpoint, which I will explain because we just don’t breathe there.

Once I heard a coach say breathing into your chest wreaks havoc on your health and is one of the worst things you can do for your body.

Our clients have enough to worry about, and now breathing is bad for their health?

I use to coach belly breathing. It’s what I was taught. I used it with every client every day and every time I coached. I use it in my own training daily.

I would tie the bands around their waists and say, “Breathe into the band.” I would put my hands on either their sides or on their belly and push my hands in and say, “Breathe into my hands.”

But the whole time while doing it, it never made sense to me because watching my client’s rib cage intently and how I felt while doing it, something didn’t seem right.

Things just seemed a little off when they were pushing their belly out as opposed to getting movement where their lungs were, the rib cage/thoracic cavity/chest whatever you want to call that area.

It wasn’t until I started massage therapy and being in a clinical setting did things start to really click. Trying to get my clients to breathe through their belly resulted in them just pushing their belly out.

Things are a lot different when you’re dealing with general population with little to no experience in a gym setting or experience in athletics of any type. I wasn’t getting the result I wanted. I was simply getting people pushing their belly out and having their bottom ribs pop up, arching their back, and honestly, they looked like they were doing this weird belly dance, trying to figure out what it was I was looking for.

It wasn’t until I put my hands on their rib cage while applying pressure and telling them to breathe into my hands that a light bulb went off. While I had my clients’ best interest in mind with belly breathing, I just lacked the knowledge.

RELATED: How to Communicate Clearly to Potential Clients

As one of my mentors always told me to know what you don’t know. And I simply didn’t know or understand breathing mechanics. My goal is to give you the knowledge and arm you with one of the best tools you’ll encounter.

How can breathing mechanics get messed up?

“How did I get this way?” is a question many of my clients and patients ask when we start to work on their breathing. They’ll often say, “My breathing can’t be bad if I’m still alive.” But our breathing has merely adapted to our own personal environment.

When we assess breathing, we typically just look at what the chest does and what the belly does. The client takes a breath, and we see movement in the upper chest, we automatically say they are a chest-breather and assume they have bad breathing patterns. We need to understand why the majority of people has this pattern. This is simply a shallow breathing pattern.

This shift to shallow breathing is mainly because of two factors: The first is an adaptation to what the body encounters from a movement perspective on a daily basis. Think of it as if you were sitting all day — there’s not going to be much movement in the hips. Then, when you go to do a movement that involves a full range of movement of the hips, you may encounter situations such as “my hips feel tight.”

Breathing is no different; if you don’t utilize proper breathing mechanics daily, it leads to poor utilization of our respiratory muscles.

The second major cause of shallow breathing is stress: working long hours, our commutes, financial pressures, relationships, the weather, pollution, and even noise. We are in a constant state of being stressed out or a sympathetic state that most of you know as fight or flight when we need to be spending more time in a parasympathetic state doing things like resting and digesting along with feeding and breeding.

If we are constantly stressed and have poor breathing mechanics, we can end up stuck in this continuous cycle where our stress causes shallow breathing and shallow breathing causes our stress. This will eventually turn this shallow breathing pattern into a habit, meaning we are now turning stress into a habit.

This isn’t what this article is about, but a constant state of shallow breathing and stress hormones running through our bodies can lead to some serious issues like a decreased immune system, increased recovery times, anxiety, depression, fatigue, weight gain, respiratory problems, and even cardiac issues. For the majority of the people we will encounter, it will also create tension in other parts of the body, which is when we start to see poor posture and poor movement patterns along with aches and pains where there shouldn’t be aches and pains.

If we teach our clients proper breathing mechanics, we can lower their blood pressure, reduce their heart rate, get their nervous system to go into a parasympathetic state, decrease stress, and relax. There is a lot of science behind how diaphragmatic breathing can help things like anxiety, depression, and intense emotions and experiences feel less threatening. It can bring us to a state of mindfulness, which is something we all need more of in our life.

Why can’t we breathe into our bellies?

Honestly, it’s impossible. From an anatomical standpoint, we just aren’t set up in such a way. Our lungs are in our chest, which is separated from the abdomen and its contents via the diaphragm.

READ MORE: The Mind-Muscle Link: Engagement and Focus

This is when most coaches object with a “Well, yeah, but you know what I mean, you’re just being nit-picky and splitting hairs at this point” statement to defend belly breathing. Or are you just being lazy as a coach? Or you don’t truly understand breathing mechanics. Either way, I understand it, I was in that position before, saying the same thing.

We should be diaphragmatic-breathers. The problem is most of us are shallow breathers. This is where we only see slight movement in the upper portion of the rib cage (ribs 1-6) and when we would say oh, they are a chest-breather.

What many of us are looking for is deep breathing aka diaphragmatic breathing/eupnea. Most people say that cues like “belly breathing,” “expand the belly,” or “push the belly out” allow for better diaphragmatic breathing, but I disagree. Stop being lazy as a coach and teach people how to breathe with their diaphragm, which is the main muscle we use to breathe with.

Understand how dysfunction can happen. For example, if the foot isn’t doing its job, something else has to do the job of the foot. If the foot isn’t stable when we run or jump or walk, we start to see issues up the chain: knee, hip, low and/or back pain because somebody now has to do the job of stabilizing the foot.

It’s the same with the diaphragm. If the diaphragm isn’t doing its job the way it should, other muscles will have to help out, which will result in issues all over the body. We want the diaphragm to do the job of the diaphragm and everything else to just do their job.

I read in a recent article on belly breathing there are supposedly thousands of studies on chest breathing and how bad it is for you. I went to PubMed, ResearchGate, and the NSCA journal and typed in “chest breathing.” I figured it would be easy to find such studies since there are thousands out there.

I want you to go to these sources and tell me how many studies come up showing you how bad chest breathing is for you.

Maybe I’m using the wrong terminology during my search. If this is the case, then please let me know. If anybody has a reputable study showing me how bad chest breathing is and belly breathing is superior, please email them to me, as I may have missed one of the thousands out there. Please don’t email me blogs; those aren’t studies. If I am wrong, I will submit a new column stating I was wrong. I’m talking about studies on belly breathing, not diaphragmatic breathing.

If you want your clients to be deep-breathers, switch into parasympathetic at the flick of a breath, teach them how to chill, have them become better movers, and increase their performance significantly diaphragmatic breathing is the way, and belly breathing is just in your way.

Breathing 101

Breathing starts with external respiration. It’s the act of bringing air into our lungs and releasing air into the atmosphere. Once oxygen is brought into the system, we move into internal respiration where oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged between the cells and blood vessels.

LISTEN: Table Talk Podcast Clip — What is Cortisol?

To get oxygen into our system our diaphragm must contract or pull down/flatten out. The diaphragm is the dome-shaped muscle below our lungs and is the primary muscle in breathing. This creates a vacuum effect that pulls air into our lungs, which then expand. We inhale air through our mouth and nose, which helps moisten the air and trap particles we don’t want in our lungs.

The air then passes through the pharynx, larynx, and into the trachea (windpipe). The trachea divides into the left and right bronchi, which divide into smaller bronchi, and then into bronchioles, and finally, the air arrives at these tiny air sacs called alveoli, which is where gas exchange occurs and internal respiration begins.

Once oxygen is brought in, it will exchange places with carbon dioxide between the cells and blood vessels. Then carbon dioxide is brought back to the lungs to be exhaled out into the atmosphere.

This is important because many of you aren’t getting a good enough exhale. The only time air gets into the abdomen is during internal respiration when oxygen is being delivered throughout the body via red blood cells. If air is getting into your belly any other way, you have a medical emergency.

What are we looking for?

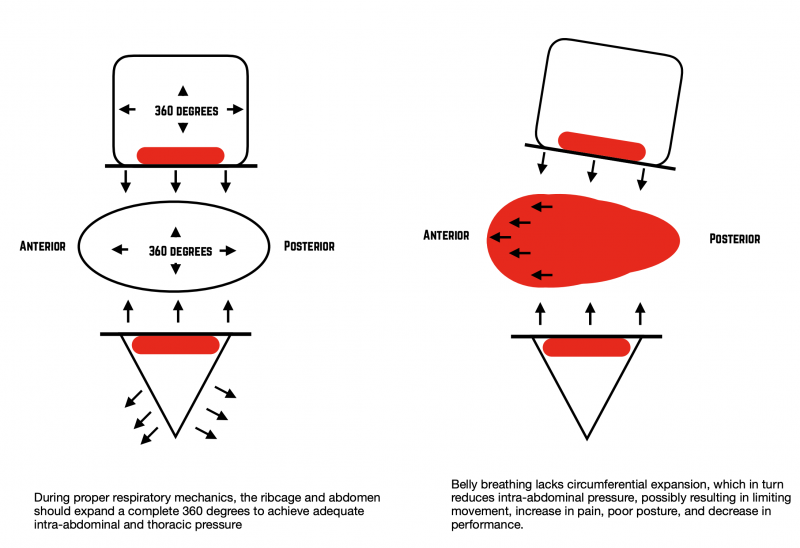

A good breath should consist of the diaphragm descending, a 360-degree expansion of the thoracic cavity, and expansion of the abdomen along with expansion into the upper rib cage and pelvic floor. Yes, the abdomen does expand, but this is because of the diaphragm contracting down and pushing the abdomen out, this is required for proper breathing.

Think of a balloon: If you push straight down it expands in all directions; if you just push the back half, it only expands out of the front. If you just breathe into your belly, you won’t have proper pressure in all directions; instead, you’ll have poor movement of the diaphragm, poor gas exchange, and it also puts your spine at risk.

We want the belly to expand; we just don’t want it to be the only thing that expands. When pressure is evenly distributed in both thoracic and abdominal cavity, it allows for optimal stability of our spine.

One way it puts the spine at risk is when the belly pushes out anteriorly (toward the front), we typically see the bottom of the rib cage raise ever so slightly and stick out anteriorly just a bit on inhalation. This causes movement in the spine around the thoracolumbar junction (T11-L1), where a lot of clients typically have pain.

Think about it: Taking hundreds of thousands of breaths like these places a lot of stress on the back over time. I’ve had a majority of my clients come into the clinic with a lifetime of pain in this area and just fixing their breathing mechanics has a life-changing effect.

The thoracic spine is a mobile joint. It needs to be able to expand as the lungs expand. I’ve found that increasing thoracic mobility, teaching how to breathe with the diaphragm and how to breathe into all aspects of the thoracic cavity has had dramatic effects on overall health and well being of my clients. I’ve seen posture improve, long-time pain dissipate, and stress released, all through the art of teaching proper breathing mechanics.

Correct Exhalation

One of the biggest issues I’ve encountered is people having poor exhalation. Think about someone telling us to “take a deep breath,” when what they should be saying is “let go of a big breath.”

If you have poor exhalation, we have poor inhalation. If you take a deep breath but don’t fully exhale, the diaphragm will actually be in a constant position of flat or inhalation. If we are constantly in this position, we will see a handful of movement limitations and what many of you consider poor posture.

Fix their breathing and watch what their posture does. If we are in a constant state of inhalation, this leads to partial motion of our diaphragm and can actually cause respiratory muscles to weaken and move less than optimally, which is where we start to see dysfunction.

Without full exhalation, we can retain carbon dioxide, which is a known stressor to our nervous system. If CO2 remains in the lungs, our body sends a signal to inhale because it feels we need more oxygen, but we don’t get enough because we haven’t fully emptied our lungs out.

Oftentimes, this leads to a cycle of stress — the common shallow breathing we see, as I mentioned prior.

Enhance T-Spine Mobility and Rib Cage Expansion

T-spine mobility isn’t just for the shoulder joints. I feel many of us do T-spine mobility but don’t essentially understand why. Go to YouTube and type in “inflating human lungs.” You will see just how much the human lungs can actually expand. What this means is one of the only limiting factors preventing the lungs from fully expanding is the rib cage ability to also expand.

Where a lot of people come into issues with breathing is due to the fact they don’t have great T-spine mobility or expansion ability of the rib cage. The lungs are enclosed in this container (rib cage), and if this container doesn’t have the ability to expand, the pressure/expansion has to go somewhere else.

We typically see this resulting in the bottom ribs coming up to make room for the diaphragm as pressure increases, leading to the stressing of the lower T-spine and low back, which then leads to the problems already discussed.

T-spine mobility and rib cage expansion are extremely important parts of your breath work. The more the ribs can expand, the more the lungs can expand, and the more oxygen/fuel we can bring in to the system. Remember: Breathing essentially is to maximize gas exchange/energy delivery/getting rid of waste, and everything else breathing benefits is a seriously positive side effect.

How to Coach

This is how I start with everyone I encounter:

- Fully and somewhat forcefully exhale through pursed lips

- Hold for three to four seconds, taking note of what the ribs and belly do

- Now inhale, keeping the ribs down, working to fully expand the thoracic cavity, which will lead to some movement in the belly but not the type of movement we may be used to seeing

- The goal is to get 360-degree expansion throughout

Wait, what? That’s it?

What? Were you looking for a lengthy checklist?

First, put your hands on your belly and “breathe into your belly,” and take note of how that feels.

Now, purse your lips and exhale fully for eight to ten seconds. You should hear an audible exhale. Take note of what your ribs do and how your abdomen feels. Keep your ribs down, inhale through your nose, and work to fully expand your thoracic cavity. Hold this breath.

Take note of how everything feels compared to the belly breath. You should feel 360-degree expansion of both the thoracic cavity and the abdominal cavity. It should feel more stable all around with better movement in the thoracic region. Do this a few times, and then tell me how you feel.

Quick Closing

I hope I made you think about breathing a little differently and why belly breathing may not be the best cue to use with your clients and patients.

As a coach, you owe it to your clients to know the proper mechanics of breathing along with the proper mechanics of everything else you train.

Be warned: If you’re interested in breathing, it’s a deep rabbit hole, but it’s also one of the best things to learn about and is an extremely valuable tool to have when it comes to working with people every day.

Reminder

- Question everything

- Knowledge against all nonsense

- Death to the belly breath

— Coach Nic

Spot on!

I absolutely concede that belly breathing may not be a good bracing mechanism for your lifts, but I don't think you should discount it entirely from your life.