Call me crazy, but there’s something special about aggressively throwing as much weight as possible over your head. If you happen to think the same, this article is for you. In the next few minutes, we’re going to be looking at exactly how to design your Olympic weightlifting program. We’ll start with two of the biggest pitfalls to avoid before moving on to the key rules you’ll need to follow. Then we'll end with some detailed examples of what a solid weightlifting program might look like.

Let’s get started, shall we?

Weightlifting Programming–2 Ways to Mess It Up

Over the last few years, I’ve had the opportunity to review A LOT of people’s weightlifting programs (including newer coaches), and I’ve noticed two big errors.

1. Not Including Enough Strength Work

Newer lifters and coaches tend to forget that weightlifting is fundamentally a strength sport. If you can’t deadlift 180kg (about 400lb), then you’re not going to be able to clean it. Full stop.

Squatting two sets of three at 70-75% isn’t going to develop the leg strength necessary to make big lifts. Similarly, if you deadlift 200kg, but your weightlifting program has you doing nothing but pulls at 60-90kg, it isn’t going to increase your pulling strength all that much.

2. Relying Too Much on Strength Work

On the flip side of the coin, you have coaches and lifters who focus so much on strength work that they don’t actually get enough quality Olympic weightlifting practice.

I’ve seen guys who regularly squat over 200kg and deadlift over 240kg and yet can’t even snatch triple digits. No amount of strength work is going to improve their weightlifting. What they need is more practice of the specific movements.

How to Design Your Weightlifting Program

Alright, now that we know what NOT to do, we can jump into the specifics of what we SHOULD be doing. To keep things simple and actionable, I’ve broken it down into three key rules that you’ll need to follow.

1. Frequent Practice of the Olympic Weightlifting Movements

The weightlifting movements must be practiced at least twice per week, ideally three times, to maximize results. There are two reasons for this. First, research shows (Edwards 2010) that you need regular exposure to a motor pattern to master it. Second, you need to build speed strength in a biomechanically specific way to see the adaptations you want.

The good news is that because the movements are typically lighter and have no eccentric component, you can quickly recover from them (especially snatches).

2. Regular Inclusion of Squats, Deadlift Variations, and Overhead Exercises

Just like we talked about earlier, weightlifting is still a strength sport, and your squatting, pulling, and overhead strength needs to keep on improving.

A good rule of thumb is to schedule two squatting sessions, two overhead sessions, and one heavier pulling session each week.

- With the squatting sessions, I would probably have one session focus on back squats, and the other focus on front squats to maximize the carryover of strength to the clean.

- With the overhead sessions, I would recommend one session using a push press variation, and the other using a strict press variation. That way you get a good balance between learning to stabilize larger weights overhead, but also getting in some more focused shoulder strength work.

- And last but not least your deadlift variations. I say variations because I’m referring to the clean deadlift and snatch deadlift movements, in which you start your pull in the exact same position as your weightlifting movements. In my mind, they offer the best compromise between heavy lifting and positional specificity.

Obviously, you can vary the amount of strength work you do to suit your own needs, but those recommendations should give you a decent place to start.

3. Schedule Both of the Above in a Way that Allows for Recovery

So now you’ve got snatches, cleans, jerks, back squats, front squats, deadlift variations, push presses, and strict presses to fit into your training week. Ideally, you’re gonna want some core work and back work in there too. It can get a little overwhelming, and it’s easy to make a mess of it.

The best way to solve this problem is by using a heavy–light–heavy type of structure. On your heavy days, you’ll either a) go heavier, b) do more volume, or c) both of the above. Then on your lighter days, you’ll back off a bit by doing the opposite.

In the next section, we’ll jump into some examples of what that might look like in practice.

Example Weightlifting Weekly Program Structures

Training 3 Days Per Week

Note: Every session can (and should) be a challenging session because you’ll have plenty of days off to recover in between.

- Monday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats, Overhead Work

- Wednesday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats, Overhead Work

- Friday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Heavier Pulls

Training 4 Days Per Week

- Monday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats

- Wednesday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats, Overhead Strength Movements

- Friday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Pulls

- Saturday: Lighter Power Variations and Overhead Strength Movements

Training 5 Days Per Week

- Monday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats

- Tuesday: Lighter power, hang or no foot variations, overhead strength movements

- Wednesday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Squats

- Friday: Snatches, Clean and Jerks, Pulls

- Saturday: Lighter Power Variations and Overhead Strength Movements

Suggested Set and Rep Schemes

For your strength work, there’s no need to overcomplicate this. Aim for something in the range of three to five sets of three to five reps for your squats, pulls, and overhead strength movements.

With your weightlifting movements, you’ll have to think a little more about the distribution of intensity. What I mean by this is that you have three distinct intensity ranges to work with.

- 70-80%, which allows for good technical practice and high training volumes (think six sets of three reps)

- 80-90%, which allows for exposure to challenging weights and moderate training volumes (think four sets of two reps)

- 90%+, which primes the body to lift maximally and allows for minimal training volumes (think three to five singles)

The heavier you lift, the greater the specificity to competition, but the training is more taxing, and your technique is likely to break down. This is why I generally recommend performing the majority of lifts at 70-80%, some of your lifts at 80-90%, and only a handful of your lifts at 90%+.

As you become more experienced, you can slightly alter this distribution in favor of higher-intensity workouts. As a reference point, even the best lifters in the world only tend to spend around 1/8th of their training time with weights in the 90-100% range.

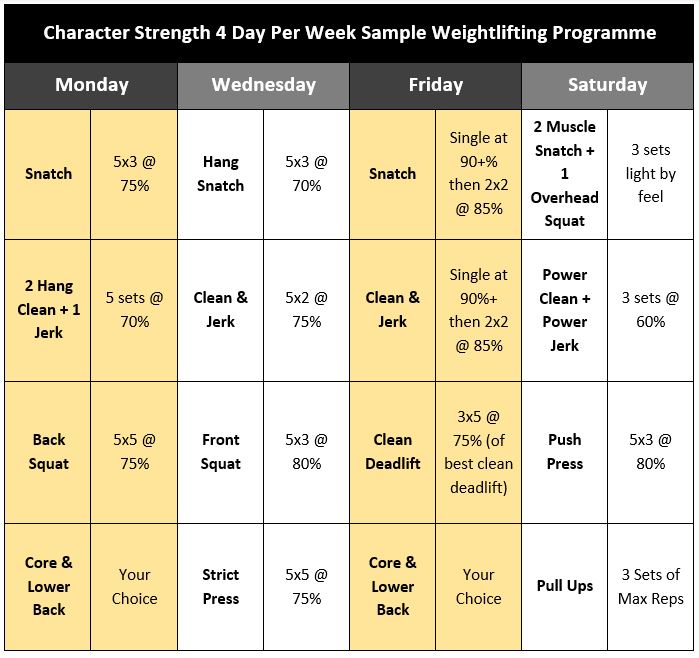

Programming

The following program is an example of a four-day weightlifting split that puts together everything we’ve talked about so far. It contains a decent amount of specific weightlifting training, alongside twice-weekly squatting and overhead work, plus once-weekly heavy pulling. It’s spread across the week using the high-low-high format, and it utilizes a balanced mix of intensity ranges for the weightlifting movements.

For progression, you would increase intensities by 1-2% per week (assuming technique was good) until a back-off week was necessary. You could then re-test your maxes at the end of the back-off week and restart the program with your new, improved numbers.

Monday:

- Snatch: 5x3 @ 75%

- 2 Hang Clean + 1 Jerk: 5 sets @ 70%

- Back Squat: 5x5 @75%

- Core and Lower Back

Wednesday:

- Hang Snatch: 5x3 @ 70%

- Clean and Jerk: 5x2 @ 75%

- Front Squat: 5x3 @ 80%

- Strict Press: 5x5 @ 75%

Friday:

- Snatch: Single at 90+% then 2x2 @ 85%

- Clean and Jerk: Single at 90%+ then 2x2 @ 85%

- Clean Deadlift: 3x5 @ 75% (of best clean deadlift)

- Core and Lower Back

Saturday:

- 2 Muscle Snatch + 1 Overhead Squat: 3x3 Light by feel

- Power Clean + Power Jerk: 3x2 @ 60%

- Push Press: 5x3 @ 80%

- Pull-Ups: 3 Sets of Max Reps

Conclusion

If you’re the type of person who skipped right to this section to get the CliffNotes version of the article (yes, you), weightlifting might not be the sport for you. On the other hand, if you’ve taken the time to read all the way through, you should now have a decent grasp of the fundamentals of weightlifting program design. In summary, you learned how to write a truly effective Olympic weightlifting program through these main points:

- Two major pitfalls to avoid

- Appropriate frequencies for weightlifting and strength movements

- Specific exercise, set, and rep scheme recommendations

- The high-low-high scheduling model

- Three main weightlifting movement intensity ranges

Header image credit: satyrenko © 123rf.com

References

- Edwards, W. (2010) Motor Learning and Control: From Theory to Practice. Cengage Learning. Pages 425-428.

Alex Parry is a strength and conditioning coach and weightlifting tutor. He currently runs his own coaching and education business, Character Strength & Conditioning. Alex also delivers education for British weightlifting.

I came across your article a few days ago while looking about information for my own training and i found it very helpful. I am 58 years old and have been doing Olympic Weightlifting since i turned 50. My best performance is in December 2019: Snatch 70k and Clean & Jerk 90k, Body weight 72K.

Can you please give me a sample of a 4 or 5 days training program? I understand I need to practice more often but at the same time recover as well in order to progress.

Thank you