On December 11, a lapse in judgement left me with bilateral calcaneal fractures, a metatarsal fracture in my right foot, and some wonderfully colourful, tender feet.

Yes, I’m a first-rate buffoon at times and thoroughly deserve much mockery.

I spent most of the next day in hospital, eventually emerging with pairs of dashing moon boots and crutches. The Doctor temporarily threatened me with casts and a prolonged hospital stay due to the bilateral breaks, so I feel fortunate that this wasn’t enforced.

Without wanting to sound like I’ve lost the plot and resorted to a self-help reading binge, the experience made many banalities of daily life challenging and fun, forced me to be creative in some respects, and reminded me to appreciate things that are often easy to overlook. In this article I will use the incident to highlight strategies I’ve used to enhance my recovery from injury, and offer tips that will hopefully improve your health too. Finally, I’ll reflect on the outcomes of the rehabilitation process, make some observations about the experience, and briefly consider some other methods that may have been useful.

This is in no way supposed to be rehabilitation advice, and I am not claiming that my approach was optimal. I do however think that my injury rehabilitation has been remarkably efficient, and I’ll provide some information to back that up.

Activity and Light Exposure

Few things are worse for health than bed rest (Saltin et al., 1968). Indeed, some think that is linked to an increased risk of events like blood clots; hence, people are commonly prescribed blood-thinning agents following many injuries. I was too but, knowing I’d stay active and look after myself, I opted not to take them. I set myself the following targets, all of which I have met to date:

Week 1: 5,000 steps daily

Week 2: 7,500 steps daily

Week 3+: 10,000 steps daily

Although there is some conflicting evidence, wearable activity monitors are useful for many to increase awareness of physical activity and thereby nudge them into being more physically active (Cadmus-Bertram et al., 2015). I certainly find my FitBit useful.

One of the great things about the boots and crutches, minus the weird looks strangers give you for clawing down the street like a tipsy quadruped, is that they make walking more metabolically taxing. I suspect my energy expenditure actually increased during this time.

During the first week or so I exclusively wore the boots, except when doing things like showering and sleeping. I gradually increased the amount of time spent with my feet unshod. On reflection, I think it’s important not to try to expedite this transition too much. Otherwise, there’s a risk of ingraining poor gait.

RECENT: Rehab and Training: Forward-Thinking Prevention, Retrospective-Thinking Treatment

I ensured that I spent more than 30 minutes outside during daylight each day to help ensure that my circadian system remained synchronised with the light/dark cycle. I also made sure that some of this took place in the morning, as some evidence indicates that morning light exposure has favourable effects on mood (Lam et al., 2016). Interestingly, recent research shows that this pattern of light exposure is consistent with that seen in preindustrial societies (Yetish et al., 2015).

Training

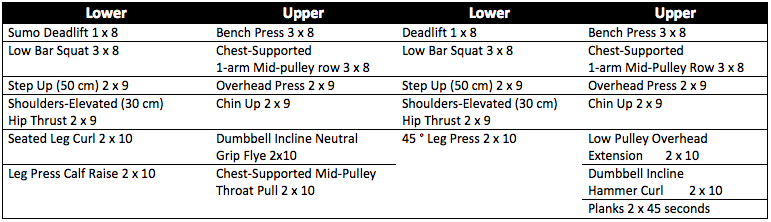

Before the breaks, I’d just begun a training period that could loosely be described as a powerlifting accumulation block in which I was using a lower/upper split training four times weekly. Since the breaks, I’ve kept the split but am training two days on and one day off, to help retain my sanity. (Occasionally this was tweaked depending on gym opening hours and whatnot.) I won’t detail specifics of the loading progressions used or anything like that; I mean only to provide a snippet of how I was training. The work sets of the lifting portions of my sessions looked roughly as follows:

After the break, I replaced the exercises requiring significant loading through the heels with exercises intended to retain muscle mass. The plantarflexors were intentionally not targeted as I felt this would load the injured tissues excessively. All training was done in boots, and lower-body warm ups comprised warm-up sets of the lifting exercises only. Post-training static stretching of the plantarflexors and squat stretches were also temporarily excluded. To try to retain my ankle mobility, I included unloaded active ankle mobility exercises daily while not wearing the boots. For the first 10 days after the breaks, training was modified as follows:

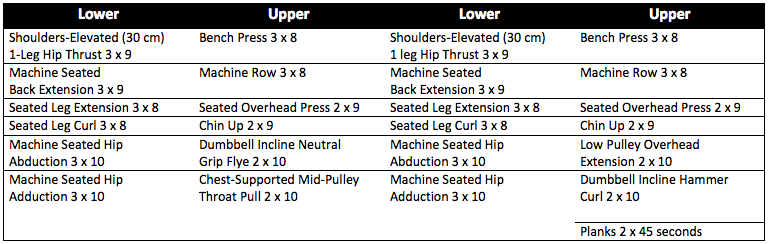

At this stage, everything was done in boots. After, the swelling and bruising were almost gone entirely. I returned to my folks’ place for nine days over Christmas and began the following:

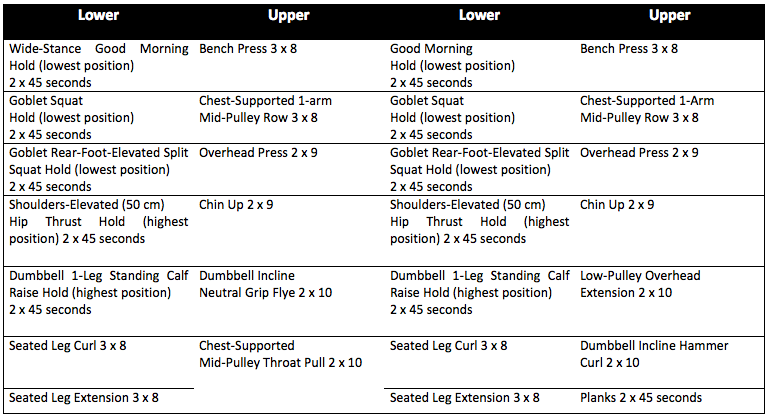

All standing exercises were now done barefoot with my heels on a foam mat. Pre-lifting lower-body warmups were included once more. Lower body lifting largely comprised static holds of more specific exercises in the lowest positions, as this reduces the loads that can be lifted. Unlike holds in other positions, there is also evidence that this method may transfer to other joint positions too, and it is particularly effective at developing flexibility through sarcomerogenesis. Furthermore, stretch can be a potent stimulus for muscle hypertrophy.

The exceptions were the hip thrust and calf raise which were held in the highest position. For the hip thrust, the rationale was to maximise motor unit recruitment; for the calf raise, the rationale was to reduce loading on the tissues around the heel. (Very high loads can be used in holds in the stretched position for this exercise.) The upper-body lifting had now returned to pre-injury exercises, as had lower-body stretches.

At this point, I was training at a different gym as my normal gym recovered from floods. I began walking outside without boots and crutches for the first time too. On January 5 I returned to the fracture clinic for an assessment. Less than three and a half weeks after the breaks, the Doctor gave me the all clear to walk without boots if I felt ready. As the normal prognosis is six weeks in a cast or boots for such an injury, I was delighted. He asked if I had been load bearing, so I briefly told him what I’d been up to. He just laughed. He suggested I must have good pain tolerance, and this is not trivial: different people’s experiences during such injuries are likely to vary greatly. I haven’t worn the boots or used crutches since seeing the doctor.

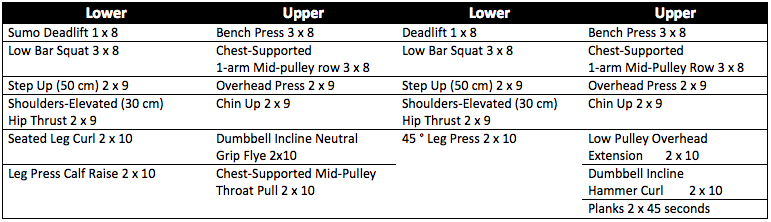

I was now ready to return to the pre-injury exercises:

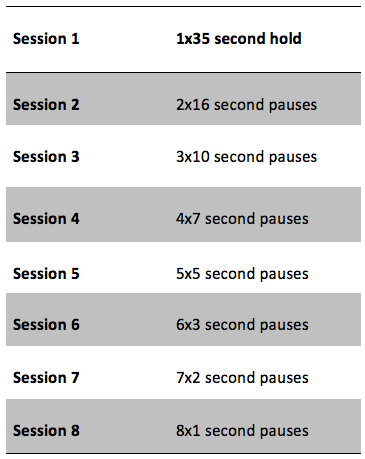

A couple of things are noteworthy. First, I have replaced step ups with front split squats. Before the injury, I had been doing step ups as split squat exercises and had been aggravating a minor adductor strain in my right thigh. With that aggravation healed, stepping down from the box with high loads would pose high impact loading on my feet. Second, loading schemes are not listed for most lower-body exercises; this is because I am using progressions based on pauses at most difficult portions of the lifts to increase loading gradually. For example, each set of the primary exercises is being progressed as follows:

I will add walking sprint drills and 10 minutes of skipping rope work on rest days (bilateral contacts) to reintroduce some impact loading. I will then progress to bilateral jumps onto soft boxes and bilateral landings from low boxes on lower-body training days, and skipping sprint drills and 10 minutes of skipping rope work (alternate contacts) on rest days. Finally, the training cycle after will include unilateral box jumps and landings, running sprint drills, and skipping rope work (unilateral contacts) on rest days. Hopefully the ways that I increased the loading in the various components of training is clear. Do ask if not.

Sleep

I’ll refrain from delving into the importance of sleep architecture, timing and duration on health. I’ll also save information on how I think many people can enhance their sleep for another time. Suffice to say, prioritising sleep can pay dividends, and a growing mass of research is documenting myriad beneficial effects of sleep extension on metabolic health, physical performance and more (Killick et al., 2015, Mah et al., 2011).

Briefly, I normally give myself at least seven hours of time in bed on all nights when I don’t go out. (On the nights that I do stay out, I cannot sleep beyond a certain time, regardless of how much I’d like to, as I’m an early enough chronotype to be diagnosed with advanced sleep phase disorder, not that I’d have it any other way.) During this period, I extended this to nine hours and tried to minimise the variability of this timing.

MORE: Sleep Strategies for Strength, Speed, and Size

Visualisation

I included visualisation of performing pain-free personal bests in lower-body lifts on rest days (minus those between and New Year’s Day), as some evidence indicates that imagery training can induce strength gains (Zijdewind et al., 2003). In a perfect world, I would have visualised entire training sessions; instead, I pictured only one set of each exercise to save time.

Nutrition

My diet is generally conducive to rapid recovery from trauma, so it changed little during this time. Specifically, it is relatively high in protein (proteins rich in the amino acid leucine help offset disuse atrophy and the associated reduced muscle function (English et al., 2015); I consume at least 30 grams of protein [to be on the safe side] from “complete” protein sources four to five times daily to maximise postprandial muscle protein synthesis (Witard et al., 2014), and I typically eat roughly 2.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body mass daily); has what is probably a favourable fatty acid composition (I eat roughly half as much oily fish as I do meat); is high in micronutrients supportive of bone remodelling like calcium and vitamin D (Prentice et al., 2006); is high in the many micronutrients and contains abundant variety (I make a point of including herbs and spices with widespread health benefits, like turmeric (Jurenka, 2009)); provides adequate energy availability to support the increased energy cost associated with trauma (very rare is the day that I don’t eat greater than 40 kcal per kilogram of body mass, for example); includes many nutrients linked to superior vascular health, such as the essential fatty acids in fish, nitrates in vegetables and polyphenols in green tea (Brown and Hu, 2001, Machha and Schechter, 2011); and contains more fibre than most diets (more than 50 grams daily).

One thing I’d note is that the injury coincided with Christmas festivities. This could predispose some to unwanted fat gain, and I was keen to avoid this. To help avoid this while still enjoying all of my favourite indulgences, I weighed myself daily under consistent conditions (before eating or drinking, after going to the toilet in the morning), a practice linked to lower body mass (Zheng et al., 2015), and restricted eating and drinking anything containing dietary energy to between 07:00 and 20:00. Emerging evidence indicates widespread metabolic health benefits of time-of-day-restricted feeding schedules in many organisms, and I’d point interested readers to the work of Satchin Panda for more on this.

During the most tasty days (like Christmas Day), I basically ate complete protein sources, non-starchy vegetables like greens, and then whatever I fancied, the idea being to maximise micronutrient density, minimise macronutrient density, meet my nutritional needs, and induce satiety while still capitalising on yummy food. This approach also reduces the likelihood of overconsuming things linked to adverse health consequences; for example, by temporarily removing fruits rich in sugars (like grapes), it is possible to enjoy your Christmas pudding and mince pies without as much worry about the deleterious effects of high sugar intakes (Johnson et al., 2009).

Supplementation

I continued creatine monohydrate supplementation during rehabilitation. I won’t go into why, as most understand the benefits of creatine supplementation on muscle mass, physical performance, and even mental health. All that I’ll add is that I took five grams daily post-training, as there is preliminary evidence that post-training supplementation may be superior to pre-training ingestion (Antonio and Ciccone, 2013).

Results

At the start of each training period, I record various anthropometric, health, and performance indices. From the injury until today, these have changed as follows:

Anthropometric

Body mass, -0.4 kg

Shoulder circumference, + 1 cm

Chest circumference, + 1 cm

Waist circumference, no change

Hip circumference, no change

Glute circumference, -2 cm

Thigh circumference, -1 cm

Calf circumference, no change

Upper arm circumference, +0.5 cm

Physiological

Resting heart rate, + 4 beats per minute

I also record my best lifts from the previous training cycles, but testing my lower body strength would be unwise at this stage.

Observations

Chronic overload protocols, like synergist ablation in animals, produce remarkably rapid skeletal muscle hypertrophy. The use of crutches produces a large increase in work on many upper-body muscles, such as the triceps brachii. Many people experience dramatic increases in upper-body muscle size and strength when forced to use crutches. I’m unaware of any published literature on the use of crutches, but studying this should be straightforward might produce some interesting findings: longitudinal measures of bone mineral density, endothelial function, muscle function, and perhaps muscle composition during use of crutches would be insightful.

Broken bones make it clear that impact loading is particularly stressful on bones. Indeed, foot-strikes while walking barefoot were far more painful than standing still under relatively heavy external loads in the early stages of rehabilitation.

The last thing I’ll add is the need for flexibility based on how symptoms change. I ended up expediting the program that I had in mind for my rehabilitation as I’ve yet to have a day where symptoms have worsened.

Other Strategies That May Have Been Useful

Had I access to pneumatic cuffs, blood flow restriction training would have been a useful method to enhance training adaptations to lower load, lower volume exercise, particularly as it appears that such training can be included very frequently (Nielsen et al., 2012). Some evidence also shows that cycles of ischaemic conditioning can help diminish disuse atrophy (Takarada et al., 2000), perhaps providing a particularly useful method in the early stages post-injury, and certain blood flow restriction protocols may induce favourable vascular adaptations to help offset the unfavourable changes typically seen during unloading (Patterson and Ferguson, 2010).

I recognise that many people advocate the use of ‘practical’ blood flow restriction exercise using elastic wraps (like knee wraps), and this is something I’ve tried before. However, the lack of control over variables like pressure dissuades me from still using this. Frankly, I think it’s arguably irresponsible recommending this to large groups of people, although I recognise that there’s little evidence of this practice being unsafe.

Had I wanted to include endurance exercise, many modalities could have been included with minimal impact on the injuries, such as arm cranking, battle rope work, and swimming. Loading progressions for locomotion exercises like carries and lunges would also be useful for many after such injuries, whereby the impact forces of foot-strikes are gradually intensified. Modifying terrain and footwear allows further manipulation of loading.

Many other strategies could also have been useful, not limited to electrical muscle stimulation, hypoxic resistance training, and various cold, hot, and manual therapies.

Conclusions

Hopefully this case study has been useful to you, either with respect to strategies that you can use to benefit your health or in providing information pertinent to injury rehabilitation specifically.

Oh yeah, and if I can leave you with one parting piece of advice then let it be this: Don’t be a muppet and hurl yourself off high walls.

References

- ANTONIO, J. & CICCONE, V. 2013. The effects of pre versus post workout supplementation of creatine monohydrate on body composition and strength. J Int Soc Sports Nutr, 10, 36.

- BROWN, A. A. & HU, F. B. 2001. Dietary modulation of endothelial function: implications for cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr, 73, 673-86.

- CADMUS-BERTRAM, L., MARCUS, B. H., PATTERSON, R. E., PARKER, B. A. & MOREY, B. L. 2015. Use of the Fitbit to Measure Adherence to a Physical Activity Intervention Among Overweight or Obese, Postmenopausal Women: Self-Monitoring Trajectory During 16 Weeks. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 3, e96.

- ENGLISH, K. L., METTLER, J. A., ELLISON, J. B., MAMEROW, M. M., ARENTSON-LANTZ, E., PATTARINI, J. M., PLOUTZ-SNYDER, R., SHEFFIELD-MOORE, M. & PADDON-JONES, D. 2015. Leucine partially protects muscle mass and function during bed rest in middle-aged adults. Am J Clin Nutr.

- JOHNSON, R. K., APPEL, L. J., BRANDS, M., HOWARD, B. V., LEFEVRE, M., LUSTIG, R. H., SACKS, F., STEFFEN, L. M. & WYLIE-ROSETT, J. 2009. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120, 1011-20.

- JURENKA, J. S. 2009. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev, 14, 141-53.

- KILLICK, R., HOYOS, C. M., MELEHAN, K. L., DUNGAN, G. C., 2ND, POH, J. & LIU, P. Y. 2015. Metabolic and hormonal effects of 'catch-up' sleep in men with chronic, repetitive, lifestyle-driven sleep restriction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 83, 498-507.

- LAM, R. W., LEVITT, A. J., LEVITAN, R. D., MICHALAK, E. E., CHEUNG, A. H., MOREHOUSE, R., RAMASUBBU, R., YATHAM, L. N. & TAM, E. M. 2016. Efficacy of Bright Light Treatment, Fluoxetine, and the Combination in Patients With Nonseasonal Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 73, 56-63.

- MACHHA, A. & SCHECHTER, A. N. 2011. Dietary nitrite and nitrate: a review of potential mechanisms of cardiovascular benefits. Eur J Nutr, 50, 293-303.

- MAH, C. D., MAH, K. E., KEZIRIAN, E. J. & DEMENT, W. C. 2011. The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players. Sleep, 34, 943-50.

- NIELSEN, J. L., AAGAARD, P., BECH, R. D., NYGAARD, T., HVID, L. G., WERNBOM, M., SUETTA, C. & FRANDSEN, U. 2012. Proliferation of myogenic stem cells in human skeletal muscle in response to low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction. J Physiol, 590, 4351-61.

- PATTERSON, S. D. & FERGUSON, R. A. 2010. Increase in calf post-occlusive blood flow and strength following short-term resistance exercise training with blood flow restriction in young women. Eur J Appl Physiol, 108, 1025-33.

- PRENTICE, A., SCHOENMAKERS, I., LASKEY, M. A., DE BONO, S., GINTY, F. & GOLDBERG, G. R. 2006. Nutrition and bone growth and development. Proc Nutr Soc, 65, 348-60.

- SALTIN, B., BLOMQVIST, G., MITCHELL, J. H., JOHNSON, R. L., JR., WILDENTHAL, K. & CHAPMAN, C. B. 1968. Response to exercise after bed rest and after training. Circulation, 38, VII1-78.

- TAKARADA, Y., TAKAZAWA, H. & ISHII, N. 2000. Applications of vascular occlusion diminish disuse atrophy of knee extensor muscles. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 32, 2035-9.

- WITARD, O. C., JACKMAN, S. R., BREEN, L., SMITH, K., SELBY, A. & TIPTON, K. D. 2014. Myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis rates subsequent to a meal in response to increasing doses of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise. Am J Clin Nutr, 99, 86-95.

- YETISH, G., KAPLAN, H., GURVEN, M., WOOD, B., PONTZER, H., MANGER, P. R., WILSON, C., MCGREGOR, R. & SIEGEL, J. M. 2015. Natural Sleep and Its Seasonal Variations in Three Pre-industrial Societies. Curr Biol, 25, 2862-8.

- ZHENG, Y., KLEM, M. L., SEREIKA, S. M., DANFORD, C. A., EWING, L. J. & BURKE, L. E. 2015. Self-weighing in weight management: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring), 23, 256-65.

- ZIJDEWIND, I., TOERING, S. T., BESSEM, B., VAN DER LAAN, O. & DIERCKS, R. L. 2003. Effects of imagery motor training on torque production of ankle plantar flexor muscles. Muscle Nerve, 28, 168-73.

Greg is a PhD student in the Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine at the University of Leeds with a focus on interactions between circadian rhythms, nutrition and metabolism. Greg has been coaching athletes in various sports for several years, has Undergraduate and Master’s degrees in exercise physiology from Loughborough University, worked in Sports Science and Sports Medicine at the Rugby Football Union, and is qualified as a Personal Trainer and Sports Massage Therapist.

Contact Greg @GDMPotter. E-mail g.d.m.potter@googlemail.com

1 Comment