Hamstring injuries are the most common soft tissue injuries in team sports such as soccer, rugby, AFL, and American Football [1,2,3]. This is likely because of the bi-articular nature of the Biceps Femoris long head (BFlh) meaning it crosses two joints. These being the knee and the hip.

Thus, the BFlh performs two major actions, hip extension and knee flexion. The BFlh is more susceptible to injury as muscle strains tend to occur when a muscle is actively lengthened to greater than normal or optimal lengths [1,2]. Extreme muscle lengthening can occur in activities such as kicking and the late swing phase of sprinting (when hip flexion and knee extension take place). This is a vulnerable position for the BFlh as it has to activate at very long muscle lengths.

MORE: Hanging Hamstring Raises to Improve Explosive Performance

Preventing hamstring injuries takes a holistic approach. That is taking into account not only what is done in the gym but on the field. Chronic sprint training load at >90 percent maximum velocity, management of fatigue, adequate sprint mechanics, and exposure to non-linear sprints are all ways to reduce the risk of hamstring injuries when on the field. In fact, sprinting alone may be enough to strengthen the hamstrings [4].

However, as strength and conditioning coaches, we want to make sure our athletes have the best chance to remain healthy and play to their potential. The training we perform off the field can add to our hamstring robustness training.

Why Eccentric Training for Hamstrings?

Eccentric-based training exercises are the go-to when it comes to training the hamstrings for robustness. Why is that?

A unique adaptation occurs within the muscle due to eccentric training where sarcomeres are added in series (lengthways) increasing the muscle fascicle length [7]. Increasing the fascicle length of the BFlh does two things:

- Increases the contractile velocity of the muscle, and

- Shifts the optimum length-tension relationship to longer muscle lengths.

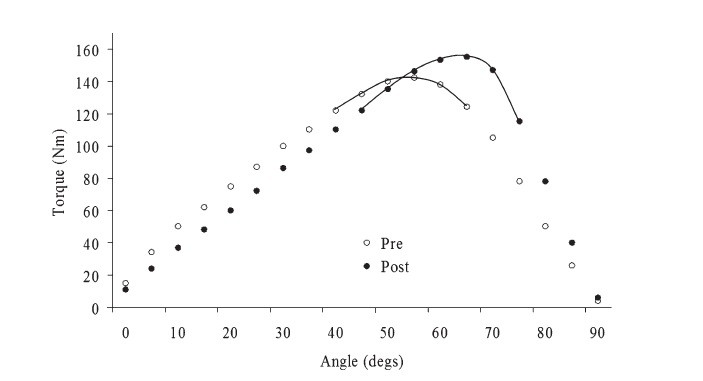

Why is number two so important? The length-tension relationship indicates there is an optimal length in which peak tension is generated [1]. As muscle length continues past this point, tension will start to decrease. This part of the length-tension relationship is considered the “danger zone” for hamstring injuries.

In fact, research has suggested that those who produce peak tension at shorter muscle lengths are more susceptible to hamstring injuries [8]. Previous injury also plays a role in optimal length where uninjured hamstrings produce peak tension at greater muscle lengths when compared to the athletes previously injured hamstring [9].

This was observed with no difference between the legs regarding concentric and eccentric strength indicating optimal hamstring length is a greater risk factor for injury than strength.

By implementing eccentric hamstring training, we can shift this optimum length further to the right which allows the hamstrings to produce peak torque at longer muscle lengths.

“Angle of Peak Torque” [10]

There are three main variables that influence the shift in optimum length [1].

- The intensity of the eccentric exercise,

- The volume of the eccentric exercise, and

- The length of the muscle during the eccentric contraction.

When working with team sports, volume is a variable that you often can’t push too far due to the acute muscle soreness and fatigue associated with eccentric training. So we will ignore volume. However, intensity of the contraction and the length of the muscle are easily manipulated within your training program. More on this to come.

Can Isometric Training Also Work?

Isometric hamstring exercise have come in vogue recently in the strength and conditioning community since Frans Bosch released his book “Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach.” Further, the work by Van Hooren and colleagues pushed the envelope when suggesting that there is no eccentric movement of the hamstrings during sprinting and that they act isometrically due to their muscle slack theory [5].

This has been widely disputed but that doesn’t discount the idea that isometric hamstring training has a place within developing hamstring robustness. It seems that isometric training can also increase fascicle length as well as muscle size [6].

Anecdotally, isometric hamstring training doesn’t lead to the same delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) that eccentric hamstring training does which makes it an alternative tool when needing to strengthen the hamstrings within a congested training schedule.

Is the Nordic Hamstring Exercise the Holy Grail of Hamstring Training?

Nordics are often painted to be the only exercise you ever need for eccentric hamstring training. And they do have some great benefits for the team sport athlete—it's a true eccentric exercise as the load being lowered isn’t able to be lifted back up. Secondly, it addresses the distal portion of the hamstring through eccentric knee extension which lacks exercise variation compared to exercises from the hip.

These benefits seem to extend into minimizing the risk of hamstring injuries within the soccer population where a 51 percent decrease in hamstring injury rates has been observed when using the Nordic hamstring exercise [11]. However, caution must be taken when interpreting these results as groups are often compared by one group performing no hamstring exercise while one does Nordics [12].

Rather than identifying the efficacy of a certain exercise, it indicates that performing Nordics are better than doing no hamstring exercise. Further, there are plenty of confounding factors as injury prevention is not about what “prehab” exercises you perform, but rather the program as a whole.

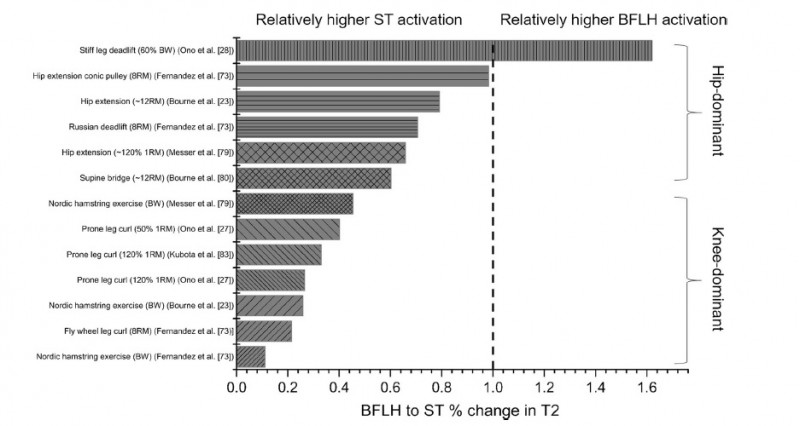

If we take a look at the Nordic hamstring exercise itself, while it provides a great eccentric overload, it doesn’t seem to activate the BFlh like hip extension exercises do [13].

“ST BFlh Activation”

If we refer back to our three variables that influence the shift in optimum length, the length of the muscle during the eccentric is one variable. The Nordic hamstring exercise falls short here as the hamstrings move from short to normal muscle length.

Further, if an athlete has a hamstring strength asymmetry, the Nordic hamstring exercise seems to exacerbate the difference [14]. Lastly, the speed of the eccentric is slow which won’t adequately prepare the athlete for the high speeds experienced when sprinting.

Taking this into account, we can conclude that the Nordic hamstring exercise isn’t the Holy Grail to training hamstring robustness but rather one piece of the puzzle.

Training for Hamstring Robustness

I’m going to break this down into three different levels. Each level will have eccentric and isometric hamstring exercise variations.

Low level

These lower-level hamstring exercises can be used in higher volumes and make great introductory exercises for the beginning of pre-season. Here are some examples:

Eccentric Backwards Pulls

I love this as a level one eccentric as it puts the hamstrings through a length change you won’t find with any other exercise. The loading is relatively light so you don’t get the crazy soreness.

Drop Squat

This is an exercise I demoed with my academic professor Matt Brughelli during my Masters' studies. Matt Brughelli created this and other drop variations and proved their efficacy in this case study with an Australian Rules Football player who had chronic hamstring injury problems [2].

This exercise variation provides a completely different stimulus to other hamstring eccentrics as the athlete has an impact to deal with before performing the eccentric which potentially transfers well to the field.

Assisted Nordic Hamstring Exercise

Many athletes struggle to control their body weight when performing the Nordic hamstring exercise which negates much of the eccentric benefits. By using a band to unload body weight, the athlete is able to control the eccentric contraction throughout the whole movement.

Supine Single-Leg Hamstring Bridge

The Supine Single-Leg Hamstring Bridge is a simple way to load the hamstrings isometrically. It can be easily progressed and regressed by changing the knee angle. As you can see in the video, I start with a more flexed knee and then move in a straighter leg placing more stress on the hamstrings.

Supine Single-Leg Band Hamstring

This is probably the lowest level hamstring exercise in this category. It makes a great warm-up and athletes like it as it feels like they are getting a hamstring stretch.

Plate Zercher Good Morning

Another variation to add to the list of extreme muscle length eccentrics. Easy to load and perform in with large groups of athletes.

Mid-Tier

These exercises I would call mid-tier hamstring exercises as they are able to be loaded heavier through their range of motion or variations can be added to the exercise.

Nordic Hamstring Exercise

Not much commentary is needed here.

Romanian Deadlift

The classic Romanian Deadlift. The staple hip extension exercise puts the hamstrings through a long stretch under heavy loads.

Eccentric Drop Lunge

This is the progression from the Drop Squat. The exercise is intensified by going from bilateral to unilateral.

Eccentric Barbell Drop Lunge

This is another progression option from the Drop Squat but is loaded with a barbell versus from a drop height.

Split Stance Staggered Stance Trap Bar RDL

This is the Plate Zercher Good Morning on steroids. By using the trap bar, athletes can load the hamstrings to a greater extent.

Prone Single Leg “Bosch” Isometric

This would be the most popular isometric hamstring variation from Frans Bosch work. The idea is to hold the isometric at the hamstring's optimal length. Being able to work up to holding a barbell with 50 percent of body weight is the target.

Prone Single Leg “Bosch” Isometric with Pulse

A progression from the isometric holds where the athlete “pulses” up and down creating mini eccentric contractions.

Prone Single Leg “Bosch” Isometric with Rotation

This is another variation to add perturbations to the movement.

High Level

In order to stimulate further response to hamstring training, exercises need to be manipulated where they can be performed with a fast contraction or by accentuating the eccentric phase through heavier load [7].

In fact, the rate of torque development from 0-100ms of the hamstrings has been observed to be correlated with sprint performance in academy soccer players [15]. Potentially, the ability to produce force quickly has implications for injury prevention when decelerating.

Drop Catch Split Stance Staggered Stance Trap Bar RDL

Drop catch variations are how exercises can be intensified through speed of contraction. By dropping and catching a bar, the hamstrings have to put on the breaks quickly to counteract the load being caught. This specific variation puts the long muscle length under extreme loading.

Drop Catch Single-Leg Back Extension

Another drop catch variation in a single leg fashion. It’s important that the movement comes from the hips and not by rounding the lower back.

Accentuated Eccentric RDL

While my demo isn’t overloaded, it shows the general principle. Lower something heavy enough that you can’t pick back up.

Isometric Hamstring Bridge Switches

I stole this variation from Alex Natera. The exercise trains the ability to produce rapid isometric force.

Isometric Hamstring Bridge w/ Med Ball Throw

I stole this variation from John Pryor. This puts the hamstrings under a completely different stressor having to decelerate the medicine ball from overhead then having to generate the force to throw the medicine ball back.

Wrapping Up

Hamstring training for sport doesn’t have to be one-dimensional. Understanding the various adaptations to types of exercise allows practitioners to progress and regress exercises accordingly.

By providing variation in hamstring exercise outside of the Nordic Hamstring Exercise, coaches are able to develop training programs to develop greater hamstring robustness and resiliency to injury.

References

- Brughelli, M., & Cronin, J. (2008). Preventing hamstring injuries in sport. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(1), 55-64.

- Brughelli, M., Nosaka, K., & Cronin, J. (2009). Application of eccentric exercise on an Australian Rules football player with recurrent hamstring injuries. Physical Therapy in Sport, 10(2), 75-80.

- Buchheit, M., Simpson, B. M., Hader, K., & Lacome, M. (2020). Occurrences of near-to-maximal speed-running bouts in elite soccer: insights for training prescription and injury mitigation. Science and Medicine in Football, 1-6.

- Freeman, B. W., Young, W. B., Talpey, S. W., Smyth, A. M., Pane, C. L., & Carlon, T. A. (2019). The effects of sprint training and the Nordic hamstring exercise on eccentric hamstring strength and sprint performance in adolescent athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 59(7), 1119-25.

- Van Hooren, B., & Bosch, F. (2017). Is there really an eccentric action of the hamstrings during the swing phase of high-speed running? Part I: a critical review of the literature. Journal of sports sciences, 35(23), 2313-2321.

- Oranchuk, D. J., Storey, A. G., Nelson, A. R., & Cronin, J. B. (2019). Isometric training and long‐term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 29(4), 484-503.

- Douglas, J., Pearson, S., Ross, A., & McGuigan, M. (2017). Chronic adaptations to eccentric training: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 47(5), 917-941.

- Brockett, C. L., Morgan, D. L., & Proske, U. W. E. (2004). Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(3), 379-387.

- BROCKETT, C. L., Morgan, D. L., & Proske, U. W. E. (2001). Human hamstring muscles adapt to eccentric exercise by changing optimum length. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(5), 783-790.

- Cowell, J. F., Cronin, J., & Brughelli, M. (2012). Eccentric muscle actions and how the strength and conditioning specialist might use them for a variety of purposes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(3), 33-48.

- Al Attar, W. S. A., Soomro, N., Sinclair, P. J., Pappas, E., & Sanders, R. H. (2017). Effect of injury prevention programs that include the nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 47(5), 907-916.

- Engebretsen, A. H., Myklebust, G., Holme, I., Engebretsen, L., & Bahr, R. (2008). Prevention of injuries among male soccer players: a prospective, randomized intervention study targeting players with previous injuries or reduced function. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(6), 1052-1060.

- Bourne, M. N., Timmins, R. G., Opar, D. A., Pizzari, T., Ruddy, J. D., Sims, C., ... & Shield, A. J. (2018). An evidence-based framework for strengthening exercises to prevent hamstring injury. Sports Medicine, 48(2), 251-267.

- Clark, R., Bryant, A., Culgan, J. P., & Hartley, B. (2005). The effects of eccentric hamstring strength training on dynamic jumping performance and isokinetic strength parameters: a pilot study on the implications for the prevention of hamstring injuries. Physical Therapy in Sport, 6(2), 67-73.

- Ishøi, L., Aagaard, P., Nielsen, M. F., Thornton, K. B., Krommes, K. K., Hölmich, P., & Thorborg, K. (2019). The influence of hamstring muscle peak torque and rate of torque development for sprinting performance in football players: a cross-sectional study. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 14(5), 665-673.

Header image credit: Volodymyr Melnyk © 123rf.com

James de Lacey is a Master of Sport & Exercise Science and works as a professional strength & conditioning coach in elite and international Rugby Union and Rugby League around the globe. He is also a published academic researcher and you can find his website at Sweet Science of Fighting.