I always find it astonishing when a coach or athlete denounces entire movements in training. Like everything in strength training, each movement serves its purpose. Some athletes need certain movements more than others, but to discredit something as “useless” just shows a complete lack of understanding of how different people need different things and that almost anything has an application. One of the biggest pushbacks I’ve seen in strongman, and other strength sports, is against the weightlifting movements, or against the clean and jerk and the snatch.

For some reason, these movements are frowned upon by a lot of people. I have no idea why. I believe it’s more of a lack of being able to do them than some sort of logical physiological belief against them. Weightlifting movements are amazing tools for strongman, and even for powerlifting. Power, mobility, and technique create a better weightlifter and are necessary in order to perform those movements well.

WATCH: The Strength Coach Development Center — Olympic Lifts Progression

Weightlifting may get a bad rap because of how technical the movements are. There is a huge learning curve when it comes to developing these skills, but one of the biggest problems I see with strength athletes is lack of proper technique, and more importantly efficiency, in almost all their movements. Learning how to do the weightlifting movements and variations of them help shore up inefficiencies that are leaving pounds on the platform.

My biggest argument for weightlifting as part of a solid, overall strongman program is that in order to be a solid strongman, you must be a solid athlete. That means that not only are you statically strong, but you’re also explosive, have good mobility, and possess great body awareness. Way too often I see strength athletes overlook basic athletic abilities, like a good triple extension, in the quest for static strength. The biggest example would be in an Atlas stone load. Why keep pounding your upper back in order to try to muscle a stone onto a platform when your hips, a much stronger and better-suited part of the body, can do the work for you? Learning to use your hips to generate power and “throw” the stone up will save you tons of pain and misery.

The hips are a much larger muscle group than the upper back and are much more able to move larger loads faster. Generating power with your hips to hit triple extension and throw a weight “upward” like in a stone load will create less overall work. Think about a clean or snatch: You’re not moving the weight with your arms so much as you are “catching” it. Granted, in full weightlifting movements, you’re dropping under the bar, but you’re still generating upward movement with your hips in order to create a position for you to drop underneath it.

Another thing I notice a lot in strongman is the inability of most people to maintain tightness in a rack position and to be able to transfer power from the legs into the press. Learning how to catch a weight in the rack position and then complete a legitimate weightlifting jerk will teach you how to transfer that energy from your legs into the bar better than anything else I can think of because if you do not do it correctly, the jerk does not count. There is no press out on a “catch”, so learning how to effectively jerk will add pounds to any other overhead movement.

Here’s the best part, though: You don’t even have to do the full movements in order to reap the benefits. Partial movements like clean and snatch pulls, high pulls, jerk from the block, etc., will help you develop the power that will carry over to being a more well-rounded athlete because you’re still learning how to generate power and hit a solid triple extension.

Finding Strength: Why Your Log Press Sucks with Zydrunas Savickas

So how do we implement weightlifting into a strongman program? “Performance preparation” is a term I learned from JL Holdsworth during my time as a strength coach at The Spot Athletics. Rather than thinking about “warming up”, you’re actively prepping your body to perform work. How do we do that? We start by “waking up” the nervous system. That means moving fast and explosively, “activating” motor units in order to move big weights quickly.

Now comes the big question: How do we effectively incorporate that into our training program? Well, the easiest way is to incorporate it at the beginning of training, keeping the load moderately light and focusing on moving it fast. I’ve noticed that cleans work better for lower body days because you can generally go heavier and prep for a solid squat or deadlift, while snatch variations work better for upper body days because you are preparing the shoulder joint for a load. This seems to work for both the full variations and the power variations.

Since the sport of strongman utilizes every aspect of athleticism concurrently—strength, power, and speed—I am a fan of a concurrent style of training. I will incorporate snatches and cleans into the beginning of my max effort days as performance prep, but I will also include them as actual dynamic effort movements on my dynamic lower days, and add in jerks and split jerks as part of my dynamic upper days. On max effort days, I am not as worried about numbers while going through the movements, as I am about moving the weight fast and feeling “ready”. This could mean no more than 50% of my training max for a few singles.

Below are a couple examples of how you can add these movements into your training program. Both will be for a four-day per week training split, but one will be for concurrent and the other non-concurrent.

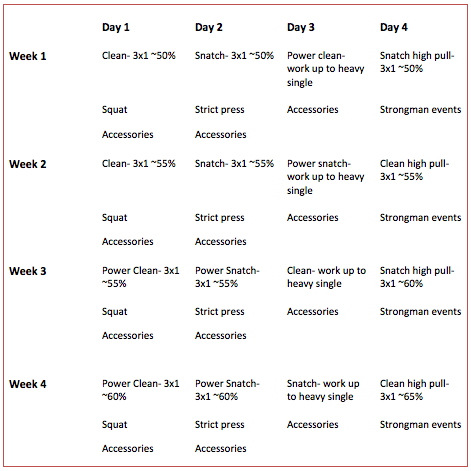

Sets x Reps, Non-Concurrent

Remember, these weights don’t have to be super taxing. The key here is to work on technique and to move the weights fast. We’re preparing to work and move weight fast. If you can’t do the full variations of these movements, stick to the power versions.

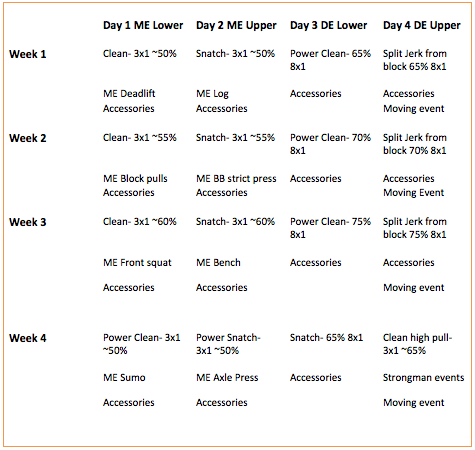

Sets x Reps, Concurrent

After you go through two weekly cycles of using the weightlifting movements as your main dynamic effort movement, you can add it in as a preparation before doing something like dynamic effort deadlifts. Anecdotally, I’ve found that adding them in before dynamic effort movements enables me to move the bar faster and have better dynamic effort training days.

A weightlifting program can look daunting to someone who isn’t in the sport, but just adding a small amount into your programming can be an extremely useful tool. It doesn’t have to be complicated, as we have seen above. If you pound technique and bar speed and don’t kill yourself, it will carry over to smoother, stronger movements across the board. The best strongman on the field is the best athlete. The more efficient you can be with the strength you already have, the better you’ll be.