From competing in the sport of powerlifting and strongman now for 10 years, I have been lucky enough to gain a lot of experience from both competing and sharing knowledge with some truly great lifters. When I first started competing in strength sports I only did powerlifting, focusing on my bench when it came to upper body. After a couple years, my best raw competition bench was 445 pounds in the 242-pound weight class. I was lucky enough to have never had an injury at this point. I had barely done any overhead work aside from some seated dumbbell press here and there, because...well, I sucked at it.

During a charity event of all occasions, I fully ruptured my pec major, splitting the muscle right in half. This was the first point in my career that I realized I’m not invincible like I thought. We all have that moment where your lifting is going great, nothing hurts, and then you are brought back down to earth as a mere mortal. I’m sure many of you out there have experienced a pec tear, as they are so common from heavy benching.

WATCH — Coaches Clinic: Overhead Press Progressions

Coming back from surgery fully recovered, I got back into benching again, and slowly increased my weights each week. The road to recovery from a major injury can be a very difficult thing to bounce back from. Once you are feeling back to 100%, you want to jump right back to the weights you could move before. Let me tell you right now, it is even more important to progress very slowly then it was as a beginner! One day my bench was going great and I felt stronger than ever. I was doing reps with 405, and I felt a rip in my other pec. I immediately knew what it was, as the feeling was still fresh in my mind from my other tear. Luckily it was just a small tear that was able to heal on its own in a few weeks, and I was able to train hard again. As many of you who have been in the sport for a while know, injuries are part of the game. I hate to say it, but if you push yourself to the absolute limit, it’s just a matter of time before you get injured. How this injury affects you mentally is what separates the average lifters from the great ones.

During my second pec tear I was getting into the sport of strongman, as I needed a new challenge after competing in powerlifting for a few years. As I said earlier, I hardly focused on my overhead pressing at all, so it was a huge weak point for me. Strongman is all about overhead, with it not being uncommon for there to be two pressing events in a competition. I remember testing my strict press and failing miserably at 275 at a bodyweight of 255 pounds. I even tried 275 pounds again with reverse bands and it wouldn’t budge. I’m someone who gets pretty frustrated when I’m weak at something, so I focused intensely on my overhead, and completely took flat benching to the chest out of my program. I was taking a break from powerlifting, and with a couple pec tears holding me back, focusing on overhead is just what I needed. After a few months of training strongman pressing and barbell strict pressing, I was able to strict press 320 pounds. Now, I took flat benching out but I still worked on two- and three-board pressing to give my pecs a break and just focus on lockout strength. An example of my accessory overhead day would look like this:

- Standing Strict Press: Work up to heavy 1 x 5

- Two-Board Close Grip Bench: 3 x 8

- Shoulder and Triceps Isolation Work: High reps (10-15)

I say this is an example of my accessory day because day one of my program would start with a strongman overhead press, such as a log press, as this is the main priority of my training. The second overhead day is more of a bodybuilding or hypertrophy day. Before focusing on my overhead press, my pecs took over every movement, so there was a huge imbalance. As a result, my shoulders and triceps were flat out weak. I would blast the bar off my chest, but get stuck soon after. I’m sure a few inches off the chest is also a very common sticking point for many of you.

No matter how much two-board pressing I did, my lockout was not improving. This is also why I was so susceptible to pec tears. My pecs took over the movement and my shoulders were too weak to help. For any beginners out there, please learn this now: don’t just train what you are good at because weakness WILL lead to injury. I can equate this to a lifter that never front squats because it’s a weaker lift than their back squat. My favorite comparison is the lifter that only conventional deadlifts and never pulls sumo. I can’t tell you how many competitors I have seen bring their deadlifts through the roof once they trained their weaker stance. Don’t let your ego get in the way of what you need to work on.

Now, some of you may not be able to barbell press due to shoulder pain, which is very common. However, you still have a lot of options to be able to work on your overhead. Simply changing the type of bar and the positioning of your hands can make a huge difference. Many powerlifters rotate the kinds of bars they squat with due to shoulder and elbow pain from the straight bar. An example can be:

- Week 1: Straight Bar

- Week 2: SS Yoke Bar

- Week 3: Cambered Bar

If you have problems with benching and overhead, you can rotate these the same way. You have options of all kinds of specialty bars here at elitefts to choose from. I find the easiest way to not have shoulder pain during overhead is to press with a neutral grip. The Multi-Grip Log Bar works best for overhead pressing this way.

Also one of my favorites for building up the front delts is the scrape-the-rack press. These can be done seated or standing, but I prefer them seated, as I can push into the bench as I press. The idea here is to think about “scraping the paint” off the rack. I own quite a few beautiful elitefts racks that I certainly don’t want the paint scraped off, so I prefer to do these with a smooth fat bar. I like the fat bar, as it can also be easier on your wrists and elbows. Another benefit of this exercise is that it is much easier on your shoulders joints, so if you have shoulder pain give this one a try.

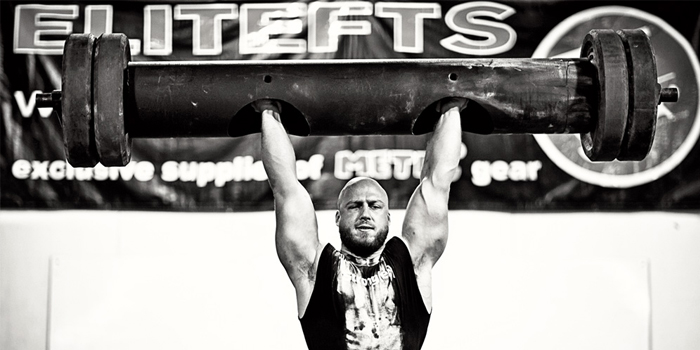

A great example of someone that has huge bench press and overhead is the legendary Bill Kazmaier. Kaz could bench over 600 pounds, while being able to overhead press over 400 pounds. You can’t argue that the two lifts didn’t carry over to each other. As any experienced powerlifter knows, the bench press is a full body lift. Any experienced strongman knows the overhead press with proper technique is also a full body lift. I recently spoke with three-time America’s Strongest Man Sean Demarinis about how he feels the overhead press and bench press are tied together. Sean was first a competitive powerlifter, and he attributes his huge overhead press to learning how to use his full body to properly bench. Sean has a raw competition bench press of 501 pounds. Here he is with a 375-pound log strict press:

I gave an example of what a day would look like while training for strongman, but when programming for powerlifting I like to use a 2:1 ratio of bench to overhead (this would be the opposite when programming for strongman).

Day 1

- Bench Press: Work up to heavy triple

- Close Grip Two-Board Bench: 3 x 5

- Pec Isolation and Rear Delt Movements: High reps

Day 2

- Overhead Press Variation: Work up to heavy 1 x 5

- Duffalo Bar Bench Press: 3 x 15–20 reps. This can also be done with a wider grip on a regular power bar.

- Triceps and Shoulder Isolation: High reps

For those of you that have followed Jim Wendler's 5/3/1, I also like to superset all overhead work with pull-ups. This is also another reason I recommend 5/3/1 to beginners, as most of them need a lot of overhead work. The balancing of pressing to pulling is also very important for shoulder health and prevention of injuries.

The main point is that you will be far less likely to be injured with stronger shoulders in the bench press. I’m a perfect example of that, as I have not had any pec injuries since my overhead became much stronger. You first need to learn how to bench with the proper technique, of course, and you have tons of resources right here at elitefts.

Matt Mills is a graduate of the University of Connecticut, earning both his Bachelor and Master in Strength and Conditioning. He is also certified through the National Strength and Conditioning Association as a Strength and Conditioning Specialist. As a strength athlete, he is an accomplished powerlifter with a best deadlift of 800 pounds. He is a middleweight pro strongman with best competition lifts of a 360-pound log press, 900-pound pound Hummer tire deadlift, and a 410-pound Farmers Walk. Matt is the owner of Lightning Fitness, located in South Windsor, Connecticut. He has worked with over a thousand athletes, helping them reach their fitness and nutrition goals.

1 Comment