Flashback if you will to October 1988. Much like today, the United States was in full-blown election mode, and with the process leading up to the actual election came a variety of political activities. Not unlike today, included in these activities were both the presidential and vice-presidential debates.

Aside from a few exceptions, the “Geraldine Ferraro debate” (first woman in a vice-presidential debate), or the 1980 “no VP” debate, these undercard debates have not been very memorable.

That said, in 1988, there was the vice-presidential debate moment of not only all vice-presidential debate moments, but perhaps of all modern day political debate moments.

Lloyd Benson was the VP candidate for the Democrats, and a young Dan Quayle was poised to be veep for the Republicans. Although they debated for over an hour, this brief 1:12 clip represents what is arguably the most memorable debate moment ever, and a moment that sowed the seeds for what the political soundbite is now measured against in contemporary modern politics. Watch the clip and we will go from there...otherwise the end of this article won’t make any sense to you.

As a powerlifter for some two-and-a-half decades, I have really been fortunate to train with and alongside of some truly great lifters. Some were great at the squat, some the bench, some the deadlift, and some all three. Programming aside and RAW vs. equipped aside, there were some commonalities among all of those great lifters. Within these common traits and practices are things like drive, determination, work ethic, consistency, attention to detail, attention to form and technique, and a definitive nuanced understanding of what each phase of each of the three lifts does for the lifter. It is the phases of the lifts that I am honing in on.

To extremely oversimplify, each of the three lifts has, in layman's terms, a “down” and an “up.” When the lifter squats, they squat down with the weight, and then they stand up. The bench is brought down to the chest, and then pressed up. And when training the deadlift, the weight is pulled off of the floor, held for a moment at the top, and then the bar is brought back down to the ground in a controlled manner. I am going to say that again: the bar is brought back down to the ground in a controlled manner.

RELATED: Grip It. Don't Rip It.

Here is what you don’t see at a powerlifting gym: you don’t see a squatter unrack the weight, squat down, then dump the weight off their shoulders as the finish for the lift. You instead see the squatter stand back up with the weight, then re-rack the bar, because dropping the weight off of their shoulders would be training just half of the squat. And, well, that just doesn’t make any sense. Training half the squat doesn’t make any sense for squat training, and it doesn’t make any sense with regard to translation to the meet. No serious powerlifter would ever negate half of this lift.

Same for the bench press: No serious lifter brings the bench bar to their chest, then has the spotter lift it off their chest until their arms are again locked out, and then repeat this half-rep down movement over and over to complete the set. They instead obviously bring the bar down to their chest, then press the bar up, and repeat this process, ultimately, locking out the weight and racking the barbell.

This is how you complete these two lifts: You complete the full down and the full up. In my two-plus decades, I have never seen a powerlifter train the squat or bench press as described above because first, you would only be training half the movement, and second...well, it would be absolutely ridiculous. These are such obvious statements. That given, this brings me to the deadlift.

As we understand how and why we train both the full squat and the full bench press, the entire range of those movements, what is the reason we see so many lifters training literally half of their deadlift? Lifters often train the deadlift by pulling the weight up off the platform then, instead of finishing the second part of the lift with a controlled descent, (a controlled down plays a critical role in strengthening the back which helps in the upward pull), the lifter either releases the barbell at the top, letting the loaded barbell crash to the floor, or they drive the bar down to hear it crash on the platform. As the kids would say, “apparently letting the bar crash down is a thing.”

Thinking maybe I was missing something, I asked elitefts team member and powerlifting legend, Steve Goggins, “what is the deal with not training the entire second half of the deadlift?” Suffice to say he is in no way, shape, or form a fan of this.

The competition aside (because the rules clearly state to lower the bar in a controlled fashion) the “down” part of the deadlift is the critical part of the movement that actually serves to help with the sheer driving force that pulls the bar off the platform.

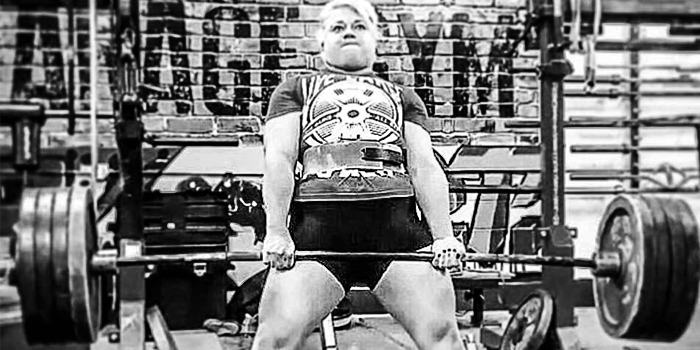

Steve Goggins: Powerlifting legend, and elitefts team member. Steve Goggins (of Goggins Force) is a deadlifting powerhouse and to this day is a huge proponent of the controlled descent of the deadlift bar when finishing the pull.

Looking back in my mind’s eye at some big, big pullers I have trained with, these great deadlifters would rip the barbell off the platform with unreal speed and power, they would hold that weight at the top for a few moments, then they would, with control and dominance over the loaded bar, slowly bring the bar down — and do so with such touch that you could hardly hear a plate move when it met the platform. If they were training reps, at the end of each rep the weights would lightly touch the platform, then the bar would be ripped off the platform again, and then the process would be repeated.

Where does this dropping the weight—or literally just blowing off the all-so-critical controlled down movement—come from? Recently I was engaged in a conversation with “The Godfather of Powerlifting” Ernie Frantz, and during this discussion he and I were talking about this half-training of the deadlift. I can assure you, nobody was dropping a bar at Ernie’s gym back during its zenith in Aurora, Illinois.

Forget about the fact that dropping the loaded barbell drastically shortens the life of the deadlift bar. Forget about the fact that dropping or slamming down the weight causes the platform to become uneven as the plates dropped from up high make an indentation into the plywood. Forget these things, but do not forget that ultimately, the sound of a crashing bar is actually the sound of the lifter blowing off 50% of the lift. Is it the CrossFit phenomenon, where bumper plates are used, and the deadlift is seen as a movement where the bar gets dropped? Is this the lifter looking for affirmation (big pullers need no affirmation)?

My favorite answer to the "why drop the bar" question is the newbie answer, ”I drop the bar, because I have seen Eric Lilliebridge do this at the end of some of his deadlifts.”

RAW deadlifting juggernaut Eric Lilliebridge, owner of a massive 903-pound pull at 308 pounds. Eric Lilliebridge has attained numerous all-time raw records in his 10 years of competitive powerlifting experience. Photo courtesy of Eric Lilliebridge.

Whenever I hear this reason for dropping the deadlift, I think back to that clip you watched at the beginning of the article and that Lloyd Benson statement to Dan Quayle in response to Quayle comparing himself to the late, great Kennedy: “Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy.” I reflect back to that lifter saying he slams the barbell down because Eric Lilliebridge does, and I always think to myself, "buddy, you're no Eric Lilliebridge." When you are pulling a massive 903 pounds like Eric Lilliebridge, then feel free to slam away now and then, as you can be assured Eric has trained his deadlift (the up and the down) and built his massive pull by working the entire movement. And he has done so under the watchful eye of his dad and coach, Sr.

If anything, a lifter who aspires to be a great puller like an Eric Lilliebridge, (903-pound deadlift at 308 pounds), like Ed Coan (901-pound deadlift at 220 pounds), like Steve Goggins (881 pounds at 259 pounds and 871 pounds at 242 pounds), or Ernie Frantz (777 pounds at 198 pounds with a pre-modern deadlift bar), needs to complete the full movement of the deadlift.

Be it in training or the meet, pull it off the platform, lock it out at the top, hold it for a two-count, and bring the bar back to the platform in a controlled manner. The reality in deadlifting is that the down helps build the up.

The deadlift is a movement where there is nowhere to run and nowhere to hide. No amount of lifting gear is going to help you be a big puller, and short-changing the integrity of the deadlift by blowing off the entire second half of this make-or-break lift only serves to rob the lifter of the power they would be building.

Steve Goggins: 947-pound exhibition pull with straps. Steve has pulled 881 pounds at a bodyweight of 259 pounds. Photo: Courtesy of Steve Goggins and Goggins Force

The importance of the down is so recognizable that I remember Ernie Frantz having extension hooks that he had fabricated and then hung from the monolift hooks. If you were a 700-pound puller, you would put more than 700 pounds on that deadlift bar, and the bar would be hoisted off the ground by the monolift jack while the barbell was lying on these hooks. Then that barbell would be lifted in place on the monolift to a height an inch or so below where you would naturally lock out your deadlift. The lifter would then grab the deadlift bar, lift it off the monolift hook extension, and stand with the deadlift bar in hand, in the locked out position. Ernie would then run the rack so now you were standing there with a weight in your hands that was greater than your deadlift max. Your job was then to slowly, in a controlled manner, set the bar back down onto the ground as if you had stood up with it in the first place and were now setting it back down.

This was an entire post-deadlifting exercise he utilized, as he felt the down was not only important, but so important that he created a way to add more than max effort weight to train just that single aspect of the movement. He did so by inventing and then using these supplemental extension hooks. I think it is safe to say that Ernie Frantz knew a little bit about the deadlift, and these lessons of his are just as germane for the serious lifter today.

With no social media showing the benefit of Ernie’s extension hook method that emphasized the absolutely critical importance of the down portion of the deadlift, the knowledge now only resides in those who were a part of that experience. Via the medium of social media, unfortunately you see poor training (training half of the deadlift would be case and point) spewed all over the net, and this turns into a monkey see, monkey do phenomenon of bad training. The newer to intermediate lifters don’t see the boring, full-rep work that the likes of a Coan or Frantz put in, as that is not the stuff that gets featured. Plus, to be somewhat blunt, those two didn’t need to be affirmed with “likes” — they were training to get stronger, not training to impress.

Having said all that, a barbell full of weight, crashing down onto a platform really sounds cool. Are we saying there is never a time to celebrate a really great pull? f that is your take-away, my suggestion is to re-read this article, because you have missed the entire point. The harsh reality is, like with all other aspects of powerlifting, there are choices to make in one’s training. In this case the choice is a pretty simple one: do you want to sound strong or do you actually want to be strong?

So, when you see your training partner drop or slam down the deadlift, unless that lifter is actually Eric Lilliebridge or some other super-human puller who has already put in years and decades of training with impeccable form and technique, my recommendation is to educate them to put in the actual work. Work the entire movement, including the downward portion, and don’t bastardize or cheapen this pillar of powerlifting by treating the second half of the lift like some afterthought at the end of a “W.O.D.”

Stated another way, respect the deadlift!

Wishing you the best in your training and competition goals.

I'd like to throw them out of the gym.