Introduction: Picking Up Where We Left Off

A while ago, I wrote a series of articles about “motivation”. My goal was to offer an evidence-based introduction to the concepts involved in motivation. The terms that expressed these concepts have been misinterpreted, misused, and presented with a judgmental, moralistic, and emotional tone in the fitness industry and pop-psychology publishing outlets. This is harmful.

In the last article of the series, I wrote about competition. Why do people compete? Why do people take part in sports – which are games, which are autotelic activities (in other words, they are an end unto themselves)? Why do six people keep throwing a ball across a net to another six people, until one of the groups fails to catch it? And why keep doing it, endlessly, until, according to a set of totally arbitrary agreements (rules), one group is considered the winner? Or why swim exactly 50 meters as fast as they can? Or… why lift the heaviest possible weight among people in a certain body-weight range?

RECENT: The Obese Body and Exercise — Physical Cross-Talk

Some individuals are not that much moved (motivate: put in motion) by others’ thoughts on the subject (extrinsic motivators), by some quest for transcendence or recovery (intrinsic motivator), by fun, by money (most of the activities above are actually costly, not profitable), or by habit. Why in the hell do they do it, then?

Apparently, some people are more prone to adhering to a long-term goal, whether it was established by themselves or not – it’s “how they roll”.

In the previous articles, I explored the role of passion, extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, goal-setting, hope, and other concepts in performance and achievement. Now I want to focus on what keeps people going. I thought I would write about discipline. When I began my (scientific) literature review about discipline, I was surprised to find how little it highlighted individual accomplishment, instead highlighting punishment. That’s a sign that it was the wrong search term. Indeed, for about a decade, the scientific community has focused on what they call “grit”.

That reading is very close to home for me: my father is a highly-accomplished scientist at the international level. He never seemed to be very aware of awards, or where he fit in a power structure. He became the most unwilling head of department in the history of science (Martha, the secretary, kept things going). Then, to his horror, for just a few months, he became the director of the institute – it was a nightmare.

What is it that made my dad successful, in spite of the fact that he couldn’t care less about success? Puzzles. He likes puzzles – all sorts of puzzles. Jigsaw puzzles: he has those 5,000-piece puzzles, and he finishes every single one of them. Suddenly I looked at the maps that he created through infinite crystallography analysis (he could spend hours on the microscope analyzing slides) of samples he had drilled after completing multiple field trips, climbing rocks, and chasing the evidence of some volcanic activity that took place over 500 million years ago, and I understood that they were puzzles. He never lets go until he solves a puzzle.

Never, in his 94 years of life, have I seen my father celebrate a personal accomplishment. I did see him smile, however, after working for days on an educational tool to explain light polarization on crystals. And again, after finishing a 3D map that he built for his students with hard cardboard sheets, razor, and glue. In technical terms, my father would be the closest you can get to an “ideal type”, defined as a concept in its pure form – which never happens in reality.

Once I figured out my father (about two months ago, when I was beginning to work on this article), I saw grit (or its absence) everywhere. It overlaps with:

- Extrinsic and intrinsic motivators

- Goal-setting

- Purpose (in its mild or extreme form, such as the mission-oriented or crusader people)

- Passion

- Persistence

Yet, some authors insist that it is still different.

I studied three physicians and researchers that were united by grit and mission: Carlos Chagas, Emanuel Dias, and João Carlos Pinto Dias. Chagas discovered American trypanosomiasis, a deadly human disease, in 1909 and spent the rest of his days trying to control its transmission. Emanuel Dias, his disciple, tried to develop methods to kill the intermediary host (the kissing bug) that dwelled in poor, country people’s shacks. Finally, João Carlos Pinto Dias, Emanuel’s son and Chagas’ godson, managed to get the World Health Organization to adopt the South Cone Initiative, eliminating disease transmission in many countries. Two died trying so that the third could succeed (Coutinho, 1999).

Vincent Van Gogh is often cited as an example of grit. Van Gogh never succeeded; he was never recognized, financially compensated, or even properly supported. In spite of his lack of resources and the severe mental illness with which he struggled until his death by suicide at age 37, he worked relentlessly on improving his technique and mastery of painting (Jamison, 1996).

Max Delbruck, the father of modern molecular biology, came to the United States in 1937 to pursue a “crazy idea” about how genetic information would be coded, transmitted, and mutated. He was mocked and neglected at Caltech. His scholarship expired and he couldn’t return to Germany, where he would be killed by the Nazis. Still, Delbruck never gave up on his crazy idea; apparently, neither did the Rockefeller Foundation. In 1945, the Phage group was established in Cold Spring Harbor, and in 1969, Delbruck and collaborators were awarded the Nobel Prize (Fischer, 1988).

A final example of extreme grit is John Forbes Nash, Jr., a mathematician who, among other awards, won the Nobel Prize in Economics. Nash suffered from severe, treatment-resistant schizophrenia. His biographies are controversial, but it is agreed that he was very sick for over 30 years of his life. Yet, he kept going, solving mathematical puzzles, even with no solid reality under his feet.

At this point, you are probably asking yourself two questions:

- When is she going to tell us how grit pushes athletes to high performance, or at least to an interesting life?

- Do I need to be “a bit different” in the head to do good?

Hang on. You’ll get the answer to the first one as soon as I define the concept. As for the second question, the answer is no – but I am not going to pretend that there isn’t a relation. The incidence of “being different in the head” is about 700% higher among those who do good, especially in the creative fields (all the arts and the sciences).

What Is “Grit”?

Grit became a technical term not too long ago. Before that, it was a word “out there”, of common usage and even considered “American slang”. It didn’t mean much more than “to push through hardship”. It’s not difficult to understand that it was mostly used in a judgmental and moralistic context. Being “without grit” was synonymous to being lazy and spoiled (Ris, 2015).

It was in 2007 that grit became a scientific concept, through the work of Angela Duckworth and collaborators in an inter-institutional research project involving the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Michigan, and the United States Military Academy at West Point (Duckworth et al., 2007). Grit became of primary interest to understand, explain, and predict academic, military, and other professional success and achievement. In other words, performance.

There are a couple of concepts that overlap with grit. Duckworth and Seligman themselves, two years before the famous 2007 publication, published a study showing that “self-discipline” had a higher explanatory power over academic achievement than IQ (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005). The quantitative analyses relied on results from the Eysenck 1.6 Junior Impulsiveness Subscale, the Brief Self-Control Scale, a Self-Control Rating Scale test filled by teachers and parents, and the Kirby Delay-Discounting Rate Monetary Choice Questionnaire. These were used against a variety of academic performance variables and an IQ test. Their results show that self-discipline accounts for twice as much of the variance on achievement in comparison to IQ.

In 2007, Duckworth and colleagues published the first quantitative tool: “In the absence of adequate existing measures, we developed and validated a self-report questionnaire called the Grit Scale” (Duckworth at al., 2007). They compared the results from this tool to IQ and the results from the Big Five Personality Traits (Goldberg, 1993). In this “foundational” article, the authors defined grit as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals”. In reading both articles, it is clear that “self-discipline”, a slippery concept that required four different tests, was easier dealt with as “grit” and a single survey. The results confirm the earlier study concerning the superiority of grit scores to IQ in predicting and explaining academic achievement (in a spelling bee) among children from several countries, college students, and military cadets. It was also highly correlated to “Conscientiousness” among the Big Five. Before 2005, there was much more emphasis on the Big Five with regard to behavioral analysis (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). Duckworth and collaborators finally developed and validated a grit scale test in 2009 (Durckworth & Quinn, 2009).

What we have now are better tools and less consensus. There are still authors referring to grit as a “character” (rather than personality) trait, and correlating it to motivational characteristics in the pursuit of happiness: “Collectively, findings suggest that individual differences in grit may derive in part from differences in what makes people happy” (Von Culin et al., 2014, Christensen & Knezek, 2014). They showed that grittier people sought more engagement and meaning in life.

We still have the repeatedly-observed correlation between grit and “Conscientiousness”, one of the “Big Five” personality trait theory components (Duckworth et al., 2007, Roland & Bartone, 2015).

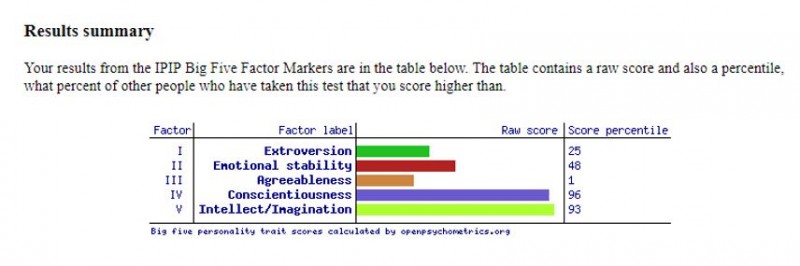

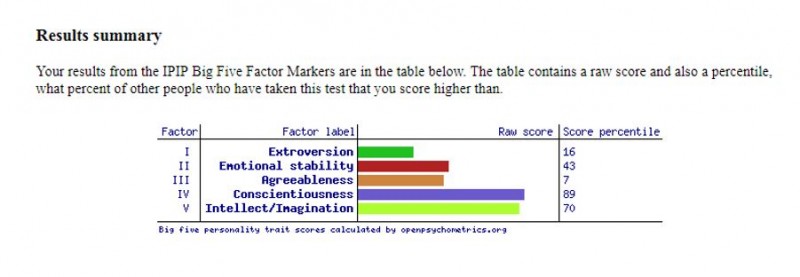

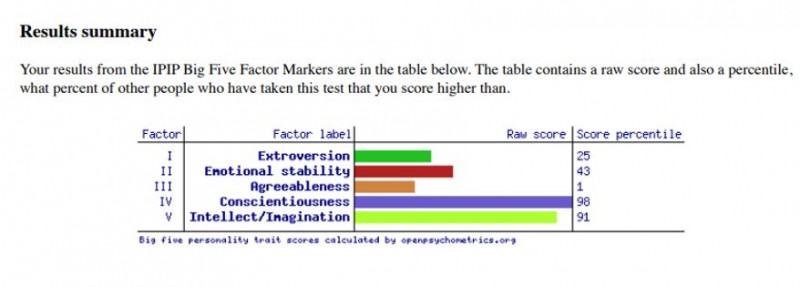

Just for fun, and because the online tests use the exact, original scholarly test questions, I took the test to measure my “Big Five” profile. I then asked two anonymous people with high levels of achievement in sports, higher degrees of academics, and in one case, military experience, to answer it as well. Here is what I got:

Mine:

Anonymous person 1 (military):

Anonymous person 2 (non-military):

Anonymous person 2 (non-military):

All these results suggest is that our personalities make sense if we consider the academic success, besides athletic and military accomplishments (Komarraju et al., 2011).

All these results suggest is that our personalities make sense if we consider the academic success, besides athletic and military accomplishments (Komarraju et al., 2011).

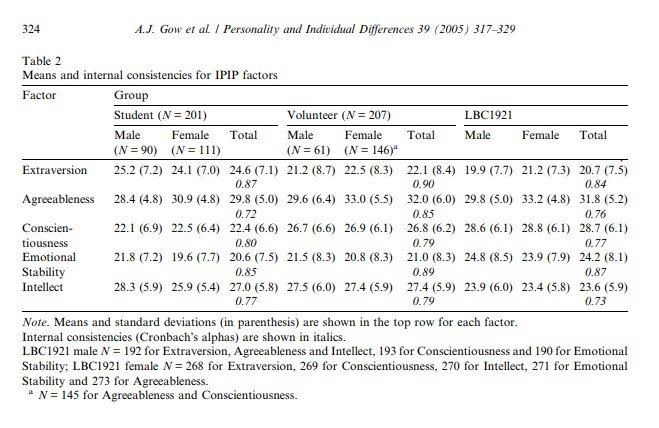

These are the scores observed in the general population (Gow et al., 2005):

The comparison between our results and those of the general population roughly suggests that having abnormal (different) internal structure is correlated with having abnormal (different) performance.

The comparison between our results and those of the general population roughly suggests that having abnormal (different) internal structure is correlated with having abnormal (different) performance.

When there are such high levels of confusion, we all look to molecular biology, genetics, and physiology for some input (Credé et al., 2017). Sure enough, they came to the rescue. Genetic studies confirm everything you read up to now: that this adherence to a certain goal-determined track is more highly-correlated with performance than other variables such as talent, IQ, or skill. However, whether they used the grit scale or Conscientiousness didn’t seem to matter (Rimfeld et al., 2016).

Cardiovascular activity was studied on undergraduates, and the authors suggest that Conscientiousness and grit are correlated with a higher capacity for physical effort (Silvia et al., 2013, Harper et al., 2018).

Another recent study on neurology proposed that “fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) in the right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), which is involved in self-regulation, planning, goal-setting and maintenance, and counterfactual thinking for reflecting on past failures,” measured by resting-state, functional, magnetic-resonance imaging, explains grit (Wang et al., 2017).

Bottom Line:

- Adherence to a goal-oriented track is what really matters for achievement (performance). See above for too many references.

- Nature and nurture play important roles. It is an inherited (genetic) trait (Rimfeld et al., 2016). It also seems to be related to neurological specificities (Wang et al., 2017).

- Grit is related to the ability to exert more physical effort (Silvia 2013, Harper et al., 2018).

- It can be undermined by stress, negative episodes, and affects (Silvia, 2016).

- It might explain illness treatment success and pain management (Nilakantan et al., 2013).

- It seems to determine consistency, learning success, adherence to rules and best practices, self-efficacy, self-control, and perfectionism (Stoeber et al., 2009, Duckworth & Gross, 2014, Hammond, 2017), and it seems to be less determined by reward (Wolf et al., 2016, Harper et al., 2018).

- There is no sex difference in grit (Ali, 2012).

- It is not a moral superiority indicator and it is not a character trait; it seems to be a personality trait, and it certainly is physiological and genetic. Making it political or moral (Mills, 2017, Ris, 2015) doesn’t help and can actually cause harm.

How Does That Reflect in Sport Performance?

If grit (or its equivalents) is so highly correlated with performance and success in fields as diverse as academic accomplishment, military tasks, and a diversity of professions and life issues (among them pain and even marriage – see Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014, and Nilakantan et al., 2013), does it explain elite athletic performance? It seems so, but research is recent and limited.

If you didn’t read anything in this article except the “bottom line” above, then you probably already inferred how it affects sports performance and what type of athlete is gritty.

Larkin and collaborators studying young, elite soccer players in Australia measured the subjects’ grit level and compared it to their performance (Larkin et al., 2018). The authors suggest that grit is not only correlated to a tendency to put more hours of work into the sport, but also to better cognitive indicators and decision-making ability.

In sports, where competition is a defining feature, again grit seems to explain success in spite of a lesser degree of reward-seeking behavior. Gritty athletes seem, instead, to feel “pride over work well done”, which explains engagement in any meritocratic activity. Gilchrist and collaborators conducted a study with undergraduate athletes and recreational runners in Canada (Gilchrist et al., 2018). They found that, “Inverse associations between global pride and grit were noted for authentic (β = .33, p < .001) and hubristic (β = -.26, p = .003) pride. Only fitness-related authentic (β = .42, p = .003), but not hubristic (β = 27, p = .053), pride was a significant predictor of grit”.

According to the authors, this suggests that grittier athletes only feel pride if success is the result of their own effort (“authentic pride”).

If you have had contact with popular writing in sports, then you’ve probably come across the derogatory expression “trophy-whore”. In strength sports lingo, that would be the lifter who loves the gold more than the iron – that’s not a gritty athlete. His or her success is driven by an extremely high level of external motivators (fame, success, money, power). As long as they last, such athletes may succeed.

But you also have, in all sports, the less-boastful, more team-committed, lower-profile athletes who will succeed – and who may even celebrate – but who you know really have a “thing” with their training routine. Some will win because they are professional athletes, and one must pay one’s bills. Still, they like the game more than the gold; the gold is an imperative.

These are the guys you may see showing extreme focus, strategy, strength, power, or speed in a competition, but who also have pride in their nice home gym, or in teaching little kids how to fight, or in just “training-and-please-pretend-I-don’t-exist-and-leave-me-alone”. These are the gritty types – they might not be too nice. There is no study concerning the Big Five profile for these folks, but high levels of conscientiousness tend to make people stubborn and focused, and that often doesn’t correlate with “niceness”. But who knows – I have three people measured. We’d need about 300 to draw any scientifically sound conclusion.

The takeaway here is supported by evidence. The gritty athlete is not only successful – there’s a high probability that he is also happier and more satisfied with his athletic activity. Isn’t it cool to be happy?

You probably suspect that the next concept to be linked to the theoretical string that I have been exploring, critiquing, and sometimes discarding, is “mental toughness”. Let’s leave it for another exploratory adventure. Keep tuned.

References

- Ali, Jaowad, and Abdul Rahman. "A comparative study of grit between male and female fencers of Manipur." The Shield-Research Journal of Physical Education & Sports Science. 7 (2012).

- Christensen, Rhonda, and Gerald Knezek. "Comparative measures of grit, tenacity and perseverance." International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 8, no. 1 (2014).

- Coutinho, Marilia. "Ninety years of Chagas disease: a success story at the periphery." Social Studies of Science 29, no. 4 (1999): 519-549.

- Credé, Marcus, Michael C. Tynan, and Peter D. Harms. "Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113, no. 3 (2017): 492.

- Duckworth, Angela L., and Martin EP Seligman. "Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents." Psychological science 16, no. 12 (2005): 939-944.

- Duckworth, Angela L., Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews, and Dennis R. Kelly. "Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals." Journal of personality and social psychology 92, no. 6 (2007): 1087.

- Duckworth, Angela Lee, and Patrick D. Quinn. "Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S)." Journal of personality assessment 91, no. 2 (2009): 166-174.

- Duckworth, Angela, and James J. Gross. "Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success." Current Directions in Psychological Science 23, no. 5 (2014): 319-325.

- Eskreis-Winkler, Lauren, Angela Lee Duckworth, Elizabeth P. Shulman, and Scott Beal. "The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage." Frontiers in psychology 5 (2014): 36.

- Fischer, Ernst Peter, and Carol Lipson. Thinking about science: Max Delbrück and the origins of molecular biology. WW Norton & Company, 1988.

- Gilchrist, Jenna D., Angela J. Fong, Jordan D. Herbison, and Catherine M. Sabiston. "Feelings of pride are associated with grit in student-athletes and recreational runners." Psychology of Sport and Exercise 36 (2018): 1-7.

- Goldberg, Lewis R. "The structure of phenotypic personality traits." American psychologist 48, no. 1 (1993): 26.

- Gow, Alan J., Martha C. Whiteman, Alison Pattie, and Ian J. Deary. "Goldberg’s ‘IPIP’Big-Five factor markers: Internal consistency and concurrent validation in Scotland." Personality and Individual Differences 39, no. 2 (2005): 317-329.

- Hammond, Drayton A. "Grit: an important characteristic in learners." Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 9, no. 1 (2017): 1-3.

- Harper, Kelly L., Paul J. Silvia, Kari M. Eddington, Sarah H. Sperry, and Thomas R. Kwapil. "Conscientiousness and effort-related cardiac activity in response to piece-rate cash incentives." Motivation and Emotion 42, no. 3 (2018): 377-385.

- Jamison, Kay Redfield. Touched with fire. Simon and Schuster, 1996.

- Komarraju, Meera, Steven J. Karau, Ronald R. Schmeck, and Alen Avdic. "The Big Five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement." Personality and individual differences 51, no. 4 (2011): 472-477.

- Larkin, Paul, Donna O’Connor, and A. Mark Williams. "Does grit influence sport-specific engagement and perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite youth soccer?." Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 28, no. 2 (2016): 129-138.

- Mills, Michele. "Reconsidering grit as a two-edged sword for at-risk students." Global Engagement and Transformation 1, no. 2 (2017).

- Nilakantan, A., K. Johnson, and S. Mackey. "Characterizing “grit” or perseverance for long-term goals in patients with chronic low back pain." The Journal of Pain 14, no. 4 (2013): S20.

- Paunonen, Sampo V., and Michael C. Ashton. "Big five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior." Journal of personality and social psychology 81, no. 3 (2001): 524.

- Rimfeld, Kaili, Yulia Kovas, Philip S. Dale, and Robert Plomin. "True grit and genetics: Predicting academic achievement from personality." Journal of personality and social psychology111, no. 5 (2016): 780.

- Ris, Ethan W. "Grit: A short history of a useful concept." Journal of Educational Controversy 10, no. 1 (2015): 3.

- Roland, Robert R., and Paul T. Bartone. "Resilience Research and Training in the US and Canadian Armed Forces." (2015).

- Silvia, Paul J., Kari M. Eddington, Roger E. Beaty, Emily C. Nusbaum, and Thomas R. Kwapil. "Gritty people try harder: Grit and effort-related cardiac autonomic activity during an active coping challenge." International Journal of Psychophysiology 88, no. 2 (2013): 200-205.

- Silvia, Paul J., Zuzana Mironovová, Ashley N. McHone, Sarah H. Sperry, Kelly L. Harper, Thomas R. Kwapil, and Kari M. Eddington. "Do depressive symptoms “blunt” effort? An analysis of cardiac engagement and withdrawal for an increasingly difficult task." Biological psychology 118 (2016): 52-60.

- Stoeber, Joachim, Kathleen Otto, and Claudia Dalbert. "Perfectionism and the Big Five: Conscientiousness predicts longitudinal increases in self-oriented perfectionism." Personality and Individual Differences 47, no. 4 (2009): 363-368.

- Von Culin, Katherine R., Eli Tsukayama, and Angela L. Duckworth. "Unpacking grit: Motivational correlates of perseverance and passion for long-term goals." The Journal of Positive Psychology 9, no. 4 (2014): 306-312.

- Wang, Song, Ming Zhou, Taolin Chen, Xun Yang, Guangxiang Chen, Meiyun Wang, and Qiyong Gong. "Grit and the brain: spontaneous activity of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex mediates the relationship between the trait grit and academic performance." Social cognitive and affective neuroscience 12, no. 3 (2017): 452-460.

- Wolf, David A. Patterson Silver, Braden K. Linn, and Catherine N. Dulmus. "Are Grittier Front-Line Therapists More Likely to Implement Evidence-Based Interventions?." Community mental health journal (2016): 1-8.

Header image credit: Wavebreak Media Ltd © 123rf.com