This is the last of a two-part series of articles about strength training for people dealing with obesity. By “dealing with,” I don’t mean treating or trying not to be obese. There is absolutely no judgement here about an obese person’s choices. Quite the opposite. What I will offer is information to both obese people and coaches about how to exercise considering some inherent difficulties of obesity.

Introduction

In Part 1, I discussed definitions, concepts, and movement aspects of training an obese person. I hope you agree with me that not only is training possible, but there are many activities an obese person can do.

In Part 2, I will address other aspects of training as an obese person. One aspect is the less visible changes promoted by exercise. These effects are still poorly understood, but they are promising and exciting.

Let’s be done with the unpleasant things so that we can move on to the fun part.

Brace Yourself Against the Bias

Let’s look at the elephant in the room: Yes, there is a stigma associated with being overweight or obese. These individuals are portrayed in the media as less attractive, less intelligent, and less educated. Selfishness, laziness, and worthlessness are also parts of an overweight person’s public image (Brownell 1991, Puhl and Bronwell 2001, and Greenberg et al. 2003). That is how you or your client may be seen, depending on your gym of choice.

Unfortunately, the bias is present in the health-care system as well. Physicians and nurses share those same values and adopt a judgmental and demeaning attitude towards overweight or obese individuals. As is well-documented, obesity is associated with higher health-care system use and costs. However, the reasons for this are not obvious: Obesity is associated with the presence or worsening of certain health conditions. The higher costs, though, may be the result of the bias cycle: The obese patient avoids medical visits to protect him/herself from humiliation and mistreatment. As a consequence, conditions are detected later than they should have been, thus increasing the complexity and cost of treatment (Schwartz et al. 2003).

The reasons for this stigma are many and complex. It is simplistic to say that those who judge you are looking only at your “poor life choices.” This is called rationalization. This is when one has an automatic conditioned response and then looks for an explanation. The fact is that a negative reaction against an overweight body involves the bombarding contents of the beauty industry marketing, such as the fear (fear of the unknown, fear of not fitting in that one faces as an outcast) and intolerance (i.e., “you are different”).

Those who understand the potential health risks from being overweight are not a problem. They know that out-of-context, unsolicited advice—or worse, judgmental hostility—has never helped anyone.

My advice to obese individuals who have decided to exercise at a gym is to “brace yourself” with knowledge. Understand that the hostility you may face is not personal and not even rational. Know your goals and make sure they are yours and yours alone.

There is nothing the people in these environments can do to you except their best efforts to make you feel uncomfortable. They are deviating from their goals and you are not. Don’t interact with them and, if possible, identify those people who are not judgmental and establish a “social space neighborhood“ in which you greet them and smile every day as they will provide normality to your training experience.

Outside the gym, well, that’s much more complicated. Honestly, you should build your network carefully. Do your best to keep your loving family members who have your best interest in mind aware that their input on the weight subject is not welcomed.

Mental Aspects of Exercising for the Obese Person: Let’s Talk About Happiness

The main reason I would suggest you engage in exercise is happiness. You might ask, “You mean managing depression?” No. I mean simple and plain happiness, although I’ll discuss depression and mental health in general soon.

Psychologists define happiness as a state of “subjective well-being” (Diener 2000). As Diener (2000) elaborates, measuring happiness is not easy or lacks a consensus among scholars. It is also confusing because it is sometimes associated with the state of satisfaction felt when all basic needs are met. Despite the controversies, quantitative scales that show interesting results relative to this subject. At all stages of life, exercise is positively correlated with happiness (Norris et al. 1992, Fox 1999, Stephens 1988, Huang and Humphreys 2012, Khazaee-pool et al. 2015).

Evidence also suggests that exercising early in life has a carryover to later-life happiness, even if the adult is inactive (Rasmussen et al. 2014).

The takeaway here is that if for no other reason, engaging in exercise can improve your “happiness score.”

With the disclaimer that any exercise beats no exercise and that I hope that the exercise-happiness connection encourages you, I must ask you to seriously consider strength training. In Part 1, I mentioned that the best exercise for overweight people is strength or resistance exercise for physical health reasons and safety. Now, I want to show you the evidence that strength training is an effective tool for improving one’s mood. It has been shown to decrease depressive symptoms (Gordon et al. 2018), anxiety (Gordon et al. 2017) and even revert cognitive degeneration resulting from mental illness (Firth et al. 2018).

There are other exercise benefits for overweight people. Obesity may be the result of a psychiatric treatment. For decades, many, if not most, psychiatric drugs (both anti-psychotics and anti-depressants) have been associated with significant weight gain. For a long time, physicians neglected patients’ complaints about this unwanted side-effect. Recently, however, it became clearer that these drugs were potentially inducing other lethal disorders associated with weight gain (Allison et al. 1999, Ferguson 2001, American Diabetes Association 2004, Berenson 2007).

By no means am I arguing that you should not, if necessary, make use of psychiatric medication to control your symptoms. Exercise can still help you require less pharmacological intervention and manage unwanted side-effects.

If you are a coach, it is important to observe if your client is not hesitating in engaging more fully in an exercise program due to perceived constraints. These can range from an actual fear of falling or getting hurt to an unwillingness to be in a hostile environment. If you reduce those constraints and create a safer environment for your client, you can help them overcome these fears (Sallinen et al. 2009).

Endocrine and Neural Aspects of Exercising for an Obese Person

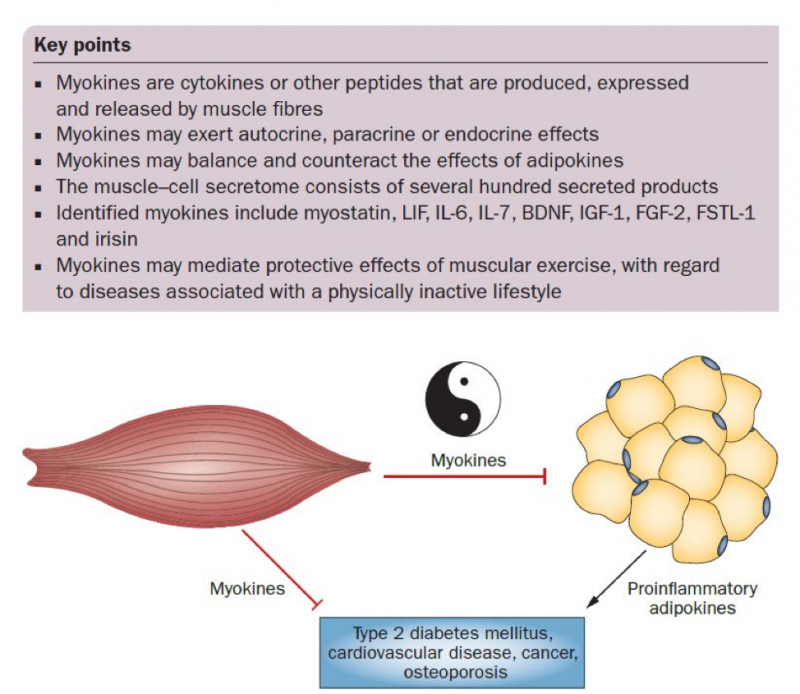

In the past few decades, our view of the benefits of exercise has changed dramatically. From an accessory activity that could increase calorie expenditure and help with weight loss, we now see exercise or physical activity as a basic human action that keeps homeostasis and health. Right after adipose tissue was shown to have endocrine activity (“act like a gland”), muscle tissue was shown to be a secretory organ. According to Pedersen and Febbraio (2012), this “provides a conceptual basis for understanding how muscles communicate with other organs such as adipose tissue, liver, pancreas, bone, and brain.”

Source: Pedersen and Febbraio (2012).

Muscles produce substances (myokines) that modulate muscle function as “cross-talk” with other organs. They are involved in pancreas function, insulin sensitivity, fat oxidation and the ability to use fat as fuel, inflammation, cardiovascular function, and much more. Secretion depends on muscle contractions during physical activity.

The new paradigm for health tends to regard physical and mental health as integrated, especially after the discovery of the complex and extensive chemical cross-talk between organs, including the brain. For example, exercise can physically change the brain, creating new brain tissue, protecting existing brain matter, and facilitating neuroadaptation (Dishman et al. 2006). These phenomena are thought to be mediated by neurotrophic factors and are involved in a variety of functions and conditions, such as cognition, mental and brain health and disorders, cancer, ischemic stroke, and head and spinal injury.

Regular exercise seems to be involved in peripheral sympathetic activity that, in turn, controls everything from heart function to immunity. Yet the exact neurochemical pathways involved in the brain, spinal cord, and muscle cross-talk are still unknown.

The high inflammatory profile associated with obesity has been known for a while. Recently, it has been shown that exercise can reduce inflammation and improve immunity, an effect that seems to be independent of fat or weight loss (You et al. 2013, Woods et al. 2009, Beavers et al. 2010).

Concluding Remarks: How to Make Exercise a Fun Habit

Making something unpleasant is hard to make into a habit. It is, however, possible, and if you look at your life, you will see that many of the things you have to make into a habit are not fun. You do these things because not doing them can have negative consequences. You may also do them because of delayed rewards. Children, whose behavior is less guided by rational considerations about future rewards or negative consequences, tend to firmly resist their parents’ insistence on tooth brushing, showering, and other habits.

But when considering physical activity and inactivity, it seems that habits incorporated in humans’ lifestyle for thousands of years have been abruptly affected by technology and new urban planning. Consider, for example, the acts of obtaining and preparing food, cleaning the living environment, or going anywhere outside it. All of these acts involve locomotion or walking. Several traditional human populations are still nomadic to this day.

Although there are genetic differences in the propensity to engage in more or less vigorous physical activities in leisure time (Stubbe and Geus 2009), humans have been active for the greater part of their history. Inactivity is something recent and, as such, it is not surprising that it negatively affects physiological mechanisms that have evolved to function in a certain way for thousands of years.

Nowhere have these contemporary urban changes been more serious than in the United States, where, in many cities, the most relevant places are not at a walking distance from homes. To make things worse, many cities have poor public transportation.

Consider this article about a neighborhood in Rome, Italy (and many similar towns in Europe, Asia, and Latin America have this spatial organization): “This Is the Best Neighborhood in Rome to Get Lost” by Elisabeth Sherman.

Image credit: www.foodandwine.com

If you look at the other pictures in the article, you will notice that these houses are upstairs from small businesses where people walk to buy their bread, groceries, and other items. Although this is contemporary Rome, as is true in many old European cities, it keeps the same urban organization it has had for centuries. Walking to places is a habit, and once it is incorporated into daily life it is easily maintained.

The takeaway here is that all you need to become active is to take the first step—in any direction with any exercise—and make it a habit. From there, it is much easier to explore other alternatives and types of exercise. Being active becomes a habit. Remember the cross-talk I mentioned before? Your body and your brain have cross-talked into maintaining this newly acquired habit. Everything in your body and mind will combine to keep you that way, including feelings of pleasure. Sounds like fun, doesn’t it?

References

- Allison, David B., Janet L. Mentore, Moonseong Heo, Linda P. Chandler, Joseph C. Cappelleri, Ming C. Infante, and Peter J. Weiden. “Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis.” American Journal of Psychiatry 156, no. 11 (1999): 1686-1696.

- American Diabetes Association. “Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes.” Diabetes care 27, no. 2 (2004): 596-601.

- Beavers, Kristen M., Tina E. Brinkley, and Barbara J. Nicklas. “Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation.” Clinica chimica acta 411, no. 11-12 (2010): 785-793.

- Berenson, Alex. “Lilly settles with 18,000 over Zyprexa.” New York Times 5 (2007): 2007.

- Brownell KD. Dieting and the search for the perfect body: where physiology and culture collide. Behav Ther. 1991;22: 1–12.

- Diener, Ed. “Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index.” American psychologist55, no. 1 (2000): 34.

- Dishman, Rod K., Hans‐Rudolf Berthoud, Frank W. Booth, Carl W. Cotman, V. Reggie Edgerton, Monika R. Fleshner, Simon C. Gandevia et al. “Neurobiology of exercise.” Obesity14, no. 3 (2006): 345-356.

- Ferguson, James M. “SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability.” Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry 3, no. 1 (2001): 22.

- Firth, Joseph, Josh A. Firth, Brendon Stubbs, Davy Vancampfort, Felipe B. Schuch, Mats Hallgren, Nicola Veronese, Alison R. Yung, and Jerome Sarris. “Association Between Muscular Strength and Cognition in People with Major Depression or Bipolar Disorder and Healthy Controls.” JAMA psychiatry (2018).

- Fox, Kenneth R. “The influence of physical activity on mental well-being.” Public health nutrition 2, no. 3a (1999): 411-418.

- Gordon, Brett R., Cillian P. McDowell, Mark Lyons, and Matthew P. Herring. “The effects of resistance exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Sports Medicine 47, no. 12 (2017): 2521-2532.

- Gordon, Brett R., Cillian P. McDowell, Mats Hallgren, Jacob D. Meyer, Mark Lyons, and Matthew P. Herring. “Association of Efficacy of Resistance Exercise Training with Depressive Symptoms: Meta-analysis and Meta-regression Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials.” JAMA psychiatry 75, no. 6 (2018): 566-576.

- Greenberg BS, Eastin M, Hofschire L, Lachlan K, Brownell KD. Portrayals of overweight and obese individuals on commercial television. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93:1342–8.

- Huang, Haifang, and Brad R. Humphreys. “Sports participation and happiness: Evidence from US microdata.” Journal of economic Psychology 33, no. 4 (2012): 776-793.

- Khazaee‐pool, M., R. Sadeghi, F. Majlessi, and A. Rahimi Foroushani. “Effects of physical exercise programme on happiness among older people.” Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing 22, no. 1 (2015): 47-57.

- Norris, Richard, Douglas Carroll, and Raymond Cochrane. “The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population.” Journal of psychosomatic research 36, no. 1 (1992): 55-65.

- Pedersen, Bente K., and Mark A. Febbraio. “Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 8, no. 8 (2012): 457.

- Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination and obesity. Obes. Res. 2001;9:788–805.

- Rasmussen, Martin, and Karin Laumann. “The role of exercise during adolescence on adult happiness and mood.” Leisure Studies 33, no. 4 (2014): 341-356.

- Sallinen, Janne, Raija Leinonen, Mirja Hirvensalo, Tiina-Mari Lyyra, Eino Heikkinen, and Taina Rantanen. “Perceived constraints on physical exercise among obese and non-obese older people.” Preventive medicine 49, no. 6 (2009): 506-510.

- Schwartz, Marlene B., Heather O'Neal Chambliss, Kelly D. Brownell, Steven N. Blair, and Charles Billington. “Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity.” Obesity research 11, no. 9 (2003): 1033-1039.

- Stephens, Thomas. “Physical activity and mental health in the United States and Canada: evidence from four population surveys.” Preventive medicine 17, no. 1 (1988): 35-47.

- Stubbe, Janine H., and Eco JC de Geus. “Genetics of exercise behavior.” In Handbook of behavior genetics, pp. 343-358. Springer, New York, NY, 2009.

- Woods, Jeffrey A., Victoria J. Vieira, and K. Todd Keylock. “Exercise, inflammation, and innate immunity.” Immunology and allergy clinics of North America 29, no. 2 (2009): 381-393.

- You, Tongjian, Nicole C. Arsenis, Beth L. Disanzo, and Michael J. LaMonte. “Effects of exercise training on chronic inflammation in obesity.” Sports Medicine 43, no. 4 (2013): 243-256.