This is a series of articles about strength training and exercise in general for people dealing with obesity. By “dealing with,” I don’t mean treating it or trying not to be obese. I mean living a happy life knowing what your choices are and dealing with misconceptions, expectations, and bias. There is absolutely no judgment about the obese person’s choice. Quite the opposite, what I try to offer here is information to both coaches and obese people about how to exercise considering some of the difficulties inherent in the condition.

Introduction

Bodies come in all shapes and forms. Various shapes and forms move differently in space. Consider the training specificities for extremely tall people, for paraplegic people, and for people with severe scoliosis. All of these people can lead healthy and active lives, but their relations with space differ from one another’s and from that of the individual closer to the “average type.” The same goes for obese people.

To start with, many exercise guided-movement machines were not designed considering adaptations for bigger people (just as many machines cannot be used by very short people). Certain movements are harder or even impossible due to mechanic impediments, like sit-ups or chin-ups, for example. Others can be done, but common sense and medical advice suggest they shouldn’t, like running.

RECENT: Intimidation and the Fitness Industry

Also, “obese” can mean many different things, and regardless of attempts to frame it with the body mass index (BMI) range, still, agility, strength, and balance will be different from one individual to the next.

To open this conversation on a positive tone, let’s watch a dancer who has no problem with being seen and known as big or obese:

Whitney Thore is a body acceptance activist. By publishing her dancing, I am not encouraging you to engage or not to engage in any identity movement. What I want you to observe is that it is possible to move and exercise while being obese.

Defining Obesity

The official definition of obesity according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is: “Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health. A crude population measure of obesity is the body mass index (BMI), a person’s weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of his or her height (in meters). A person with a BMI of 30 or more is generally considered obese. A person with a BMI equal to or more than 25 is considered overweight."

It is important to understand that your BMI doesn’t provide a diagnosis: it is a useful epidemiological indicator for institutions like the WHO to monitor the distribution of hunger (defined as the frequency of adults with BMIs of 18 or less) and overweight, its trends over time, and its regional distribution. It is also used to study the association between obesity and certain health conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Technically, this tells us that obesity is a “risk factor” for hypertension, hypercholesteremia, and insulin resistance.

A more practical approach for the individual is a personal assessment of how much, if any, his or her fat tissue is creating problems for daily life activities. The actual detection of health conditions such as those mentioned above is relevant.

Although the decision about what to do or not to do concerning weight loss is entirely yours, some things must be said:

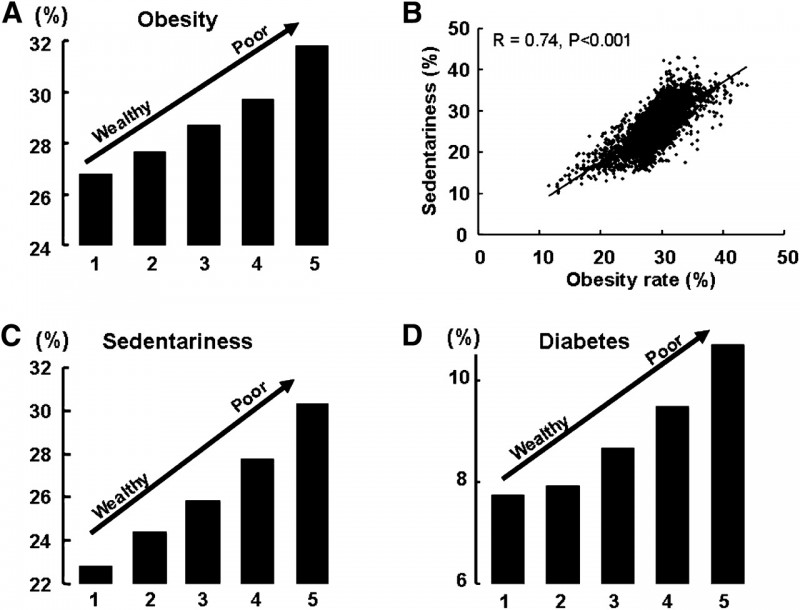

- The strong relation among poverty, educational level, and obesity suggests that some people are not obese by choice but due to the lack of proper health care services.

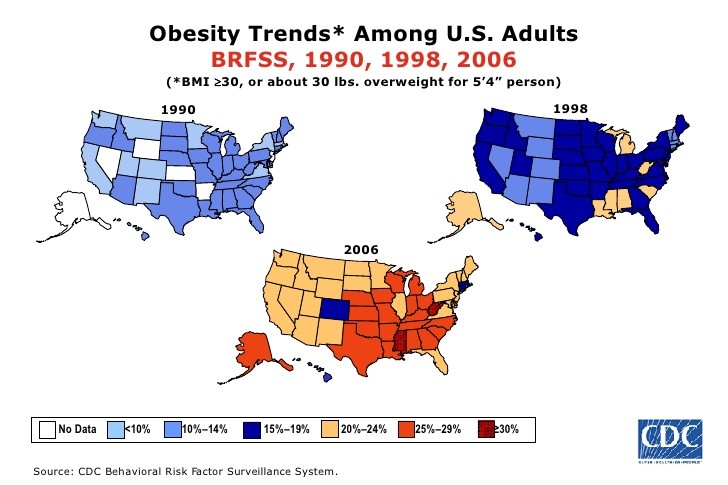

- Obesity is on the rise, especially in the USA. It is also increasing in the states with the lowest educational levels and more poverty.

- An inverse relation exists between food cost and calorie density. This means the cheapest food is the one that is the most caloric and less nutritious (Drewnowski 2004).

- Some health professionals conduct studies on strategies for obtaining healthy nutrition on a budget, but this knowledge is not always available. I volunteer in one such organization, the Latino Development Agency.

- Obesity is also associated with sedentarism, which, among other factors, is associated with the availability of training facilities. Some people may obtain free membership through social programs, such as the Latino Development Agency or Lift for the 22. There are also gyms and health clubs that offer very cheap membership alternatives, such as Planet Fitness.

- Unfortunately, because obesity also has a correlation with educational level and this is a strong determinant of information-retrieval skills, the people who most need these resources might be the ones who can’t get them.

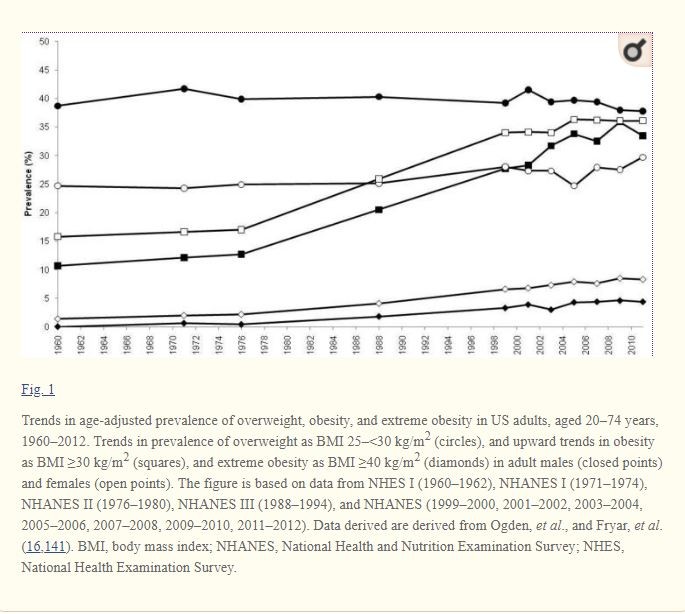

From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Hruby & Hu (2015)

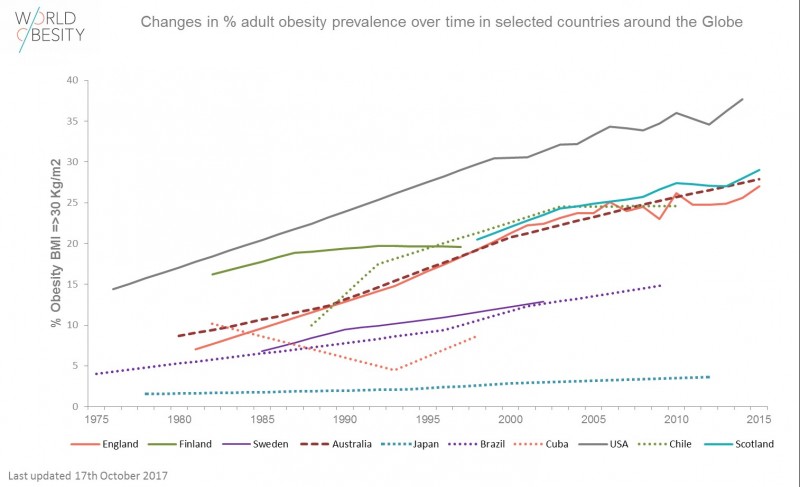

From World Obesity

From Levin (2011), “Poverty and Obesity in the USA,” American Diabetes Association

From the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Because overweight and obesity are statistically risk factors for important health issues, the focus of most physicians with obese patients who come to their offices with any health complaints ends up being diet and exercise for weight loss. This can be frustrating and even humiliating because bias exists among health care professionals (Teachman 2001, Schwartz 2003, Puhl 2010). However, here are some important reasons why you should confront the bias and exercise.

Diet and Obesity, Exercise and Obesity: What the Literature Says

The whole point of this article is to defend the idea that exercise will be good for you for many different reasons than the conventional assumption concerning weight loss. In fact, the literature indicates that exercise has, on average, a moderate to small effect on weight loss (Seiler 2000, Miller et al 1993, Miller 1999).

The metabolic effect on early-stage diabetes and the improvement of hypertension, however, are significant (Seiler 2000).

The insistence on diet and exercise for weight loss for obese individuals has been criticized in several studies. Beedie et al. (2016) have pointed out that sport and exercise science has failed to deliver its promise: with an adherence rate similar to that of pharmacological interventions, the latter is more efficient. Thomas et al. (2008), in a study conducted in Australia, suggested that obese individuals’ poor adherence to diet interventions are related to social factors and that exercise is less adopted as an option for them.

Considering these and other studies, unless exercise is turned into a pleasant, cheap, and long-term habit, it is not the magic pill for weight loss for obese individuals.

Should we then turn away from exercise and diet for obese individuals? Not at all: if weight loss is the only objective, both are important, even if not the magic bullet alone. All in all, exciting news that addresses the following questions can be found in the medical literature:

- Do you want to control your chronic conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.)?

- Do you want to control your pain (like low back pain, joint pain)?

- Do you want to improve your self-efficacy for daily life?

- Do you want to feel better?

And most of all:

- Do you want to feel more in control of your life?

As we will see in the second part of this series, exercise has such diverse neural and endocrine effects that weight loss may be the least of its benefits to the obese person (You 2013, Woods 2009). Few remember that while many obese people and physicians consider decreasing fat tissue to be a priority, it is the exercise scientist’s role to point out that gaining muscle is equally or even more important.

Why is it so important?

- The stronger you are, the less lower back and joint pain you will experience.

- Muscle is a secretory tissue: it produces substances that positively affect your well-being (Pderson & Febbraio 2012).

- Muscle is a secondary stabilizing system (with tendons and ligaments being the first) for movement.

- The more muscle you have, the stronger you will be, and the better you will handle your extra body fat.

The Obese Body: Specificities for Exercising

The obese body creates different demands on the proprioceptive and kinesthetic awareness systems. Proprioception is how you perceive your body and the space based on stimuli coming from within the body. Meanwhile, kinesthetic awareness is how you perceive your body relative to the environment through external information-processing mechanisms.

In other words, we have a problem of balance. The obese body requires more displacement to achieve the same balance as the non-obese body does (Greve et al. 2007, Berrigan et al. 2006, Hue 2007, Ku 2012). This includes seated movements. The higher the level of obesity and sedentarism, the more this effect will be manifested.

Another specificity to take into consideration concerning movement for the obese body is the burden over weight-bearing as well as non-weight-bearing joints. A high correlation exists between obesity and osteoarthritis. Studies have suggested that mechanical stress is the main factor that determines this effect (Vandenbroucke 1988, Hartz 1986).

Alternatives — Best Exercises for Obese People

Considering all of this, the best alternatives include:

Strength Training

The safest and most effective exercise for obese (and diabetic!) people is weight training: there is no impact on the joints, muscle hypertrophy provides the biggest reservoir for glucose disposal, and it can be fun (Wiley and Singh 2003). Do ANYTHING you’d like or that your coach is creating and is knowledgeable enough to offer. Basic barbell lifts are very good: they are (relatively) slow, they represent a fun challenge, and they will not create much more mechanical damage to your joints than what you experience just by performing daily tasks. The exception is if you become an extremely strong squatter as an extremely obese person. Unfortunately, I’ve seen that: it’s not good (add the barbell weight to the bodyweight and the result is damage to the knee joint). There is something in strength sports called a “Super Heavy Weight” (SHW). They are very heavy athletes. They usually carry a lot of body fat but a huge amount of muscle.

Squatting, if not that heavy, is a good alternative:

And, of course, we should never forget that getting up from a seated position might have been impossible at some point and it is the “personal record”squat for an obese person recovering from several morbidities:

Here are two self-identified obese ladies sharing their workouts. The first is a strength workout with regular equipment. The second is a home workout:

Water Exercises

Exercising in a pool decreases the burden on the joints. It is especially interesting for cardiovascular exercising. DISCLAIMER: I do not condone the discourse or the judgmental expressions, such as “indulgence.” I recommend you watch with the sound off.

Now, do turn the sound on: this is considered the most beautiful rendition of “Somewhere over the Rainbow,” by Israel Kaʻanoʻi Kamakawiwoʻole, “a Native Hawaiian singer-songwriter, musician, and Hawaiian sovereignty activist”. He died of complications from extreme obesity and appears to have used the pool to relieve his symptoms.

Balance Training

The need for this is related to the balance issues I introduced in the previous item. Clark (2004) published detailed guidelines and protocols that should be sufficient at this point.

Dancing

Let’s never forget that adherence is probably the biggest area of concern for the health professional hired by an obese person for guidance, or for the obese person who has decided to adopt a more active lifestyle. A boring and unpleasant exercise program is of no use to you: in time, it will produce negative mental effects, which beats the purpose of doing it. Dancing becomes an attractive alternative: “People naturally dance to music, and research has shown that rhythmic auditory stimuli facilitate production of precisely timed body movements,” say Iordanescu and collaborators (2013). That’s one option many obese people — both men and women — are using to stay active and happy.

Walking

Walking at a slow pace is the most common form of leisure-time physical activity. For non-obese adults, walking at this pace doesn’t provide cardiovascular conditioning benefits (although it obviously provides many others related to mental health, such as stress release, meditation, etc.). For obese adults, it does include cardiovascular conditioning benefits (Hills et al. 2016). It is a win-win!

I recommend that you refrain from exercise that causes impact on the joints, like jogging. If you do enjoy the meditative effect of a good jogging session, try brisk walking if no other impediment exists.

Take Away

If you are an obese person, it is important that you understand that the conventional mantra that says you must exercise to lose weight is, first, nuanced and, second, not the most important benefit that physical activity can provide for you.

If you are a coach and you still follow that mantra, I hope to have offered some interesting reading that may provide tools for helping your clients.

Turn your back on these mantras: they are usually partially wrong. Life is short: seek happiness. Let health be made of happiness. Let movement and strength be a tool for that.

Your body, your choices, your rules.

References

- Beedie, Chris, Steven Mann, Alfonso Jimenez, Lynne Kennedy, Andrew M. Lane, Sarah Domone, Stephen Wilson, and Greg Whyte. "Death by effectiveness: exercise as medicine caught in the efficacy trap!." (2016): 323-324.

- Berrigan, F., M. Simoneau, A. Tremblay, O. Hue, and N. Teasdale. "Influence of obesity on accurate and rapid arm movement performed from a standing posture." International Journal of Obesity 30, no. 12 (2006): 1750.

- Clark, Kristine N. "Balance and strength training for obese individuals." ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal 8, no. 1 (2004): 14-20.

- Drewnowski, Adam, and Stephen E. Specter. "Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs." The American journal of clinical nutrition 79, no. 1 (2004): 6-16.

- Girardi, Federico M., Jiabin Liu, Zhenggang Guo, Alejandro Gonzalez Della Valle, Catherine MacLean, and Stavros G. Memtsoudis. "The impact of obesity on resource utilization among patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty." International orthopaedics (2018): 1-6.

- Greve, Julia, Angelica Alonso, Ana Carolina PG Bordini, and Gilberto Luis Camanho. "Correlation between body mass index and postural balance." Clinics 62, no. 6 (2007): 717-720.

- Hartz, Arthur J., Mary E. Fischer, Gordon Bril, Sheryl Kelber, David Rupley, Barry Oken, and Alfred A. Rimm. "The association of obesity with joint pain and osteoarthritis in the HANES data." Journal of Chronic Diseases 39, no. 4 (1986): 311-319.

- Hills, Andrew P., Nuala M. Byrne, Scott Wearing, and Timothy Armstrong. "Validation of the intensity of walking for pleasure in obese adults." Preventive medicine 42, no. 1 (2006): 47-50.

- Hruby, Adela, and Frank B. Hu. "The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture." Pharmacoeconomics 33, no. 7 (2015): 673-689.

- Hue, Olivier, Martin Simoneau, Julie Marcotte, Félix Berrigan, Jean Doré, Picard Marceau, Simon Marceau, Angelo Tremblay, and Normand Teasdale. "Body weight is a strong predictor of postural stability." Gait & posture 26, no. 1 (2007): 32-38.

- Iordanescu, Lucica, Marcia Grabowecky, and Satoru Suzuki. "Action enhances auditory but not visual temporal sensitivity." Psychonomic bulletin & review 20, no. 1 (2013): 108-114.

- Ku, P. X., NA Abu Osman, Abas Yusof, and WAB Wan Abas. "Biomechanical evaluation of the relationship between postural control and body mass index." Journal of biomechanics 45, no. 9 (2012): 1638-1642.

- Levine, James A. "Poverty and obesity in the US." (2011): 2667-2668.

- Miller WC. How effective are traditional dietary and exercise interventions for weight loss? Med.Sci.Sports Exerc. 31(8), 1129-1134. 1999.

- Miller, W. C., Wallace JP, Eggert KE, and Lindeman AK. Cardiovascular risk reduction in a self-taught, self-administered weight-loss program called the non-diet diet. Med.Exerc.Nutr.Health 2, 218-223. 1993.

- Pedersen, Bente K., and Mark A. Febbraio. "Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ." Nature Reviews Endocrinology 8, no. 8 (2012): 457.

- Puhl, Rebecca M., and Chelsea A. Heuer. "Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health." American journal of public health 100, no. 6 (2010): 1019-1028.

- Schwartz, Marlene B., Heather O'Neal Chambliss, Kelly D. Brownell, Steven N. Blair, and Charles Billington. "Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity." Obesity research 11, no. 9 (2003): 1033-1039.

- Seiler, Stephen. "Exercise as Medicine." Physical activity prescription in primary health care. Agder Research Foundation (2000).

- Teachman, Bethany A., and Kelly D. Brownell. "Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune?." International journal of obesity 25, no. 10 (2001): 1525.

- Thomas, Samantha L., Jim Hyde, Asuntha Karunaratne, Rick Kausman, and Paul A. Komesaroff. "" They all work... when you stick to them": A qualitative investigation of dieting, weight loss, and physical exercise, in obese individuals." Nutrition journal 7, no. 1 (2008): 34.

- Vandenbroucke, J. P., and H. A. Valkenburg. "Osteoarthritis and obesity in the general population. A relationship calling for an explanation." The Journal of rheumatology 15, no. 7 (1988): 1152-1158.

- Willey, Karen A., and Maria A. Fiatarone Singh. "Battling insulin resistance in elderly obese people with type 2 diabetes: bring on the heavy weights." Diabetes care 26, no. 5 (2003): 1580-1588.

- Woods, Jeffrey A., Victoria J. Vieira, and K. Todd Keylock. "Exercise, inflammation, and innate immunity." Immunology and allergy clinics of North America 29, no. 2 (2009): 381-393.

- You, Tongjian, Nicole C. Arsenis, Beth L. Disanzo, and Michael J. LaMonte. "Effects of exercise training on chronic inflammation in obesity." Sports Medicine 43, no. 4 (2013): 243-256.

I practice basic lifts at my home-gym (not-good-form-snatch, not-good-form-clean & jerk, squat at power rack, bench at power rack, deadlift, ohp, barbell rows, core and elastic-band-assisted pull-ups).

These exercises fullfill all my week and due to my limitations (50 yo, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hipertension) I do not impose any agressive periodization. To be honest, I expect some 'natural feeling' that signals I can add more 5 pounds on the barbell. Also, I am preferring to do 5, or 6RMs instead of a strict three attempt 1RM. Even belts I do not use. It is just a passion.

Recently I scaped from the 40 BMI (42 initial and 39,3 today). But I know it took more than 20 year to reach such obesity and I am trying to eliminate something like 8 or 10 pounds/month (yes, I know this linearity will end soon...).