elitefts™ Sunday Edition

The above image is a work of a U.S. Army soldier or employee, taken or made during the course of the person's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

With winter in full swing in America, the jock culture has transitioned from throwing a football around outside to watching college basketball on the tube and at least thinking about getting ready for spring and the beach. Avid lifters may be bundled up in sweats at the gym, or if they are working out in the garage, they’ve added a space heater or an extra layer of clothing.

But there is a hardy group of athletes who live for those winter months when the ground is covered in white as far as the eye can see—those who smile broadly at the season’s first snowflake while others frown and head inside to throw another log onto the fire. Some of these winter athletes ski, some snowboard, and some skate, but the winter sport practiced by the biggest, strongest, and fastest athletes is sliding.

Sliding?

Yes, sliding—and it’s not for the faint of heart. Skeleton is a fast winter sport that involves a sled with a single athlete sliding down a narrow, twisting ice track face-first. Bobsled, perhaps the most recognizable sliding sport in the U.S., competes on the same banked track as skeleton and luge, with two- or four-person sled teams. Skeleton and bobsled require an explosive, running “push” start, precision when driving through banked curves at up to 5gs (a measure of inertial force that is equivalent to five-times the normal gravitational pull), and they demand that athletes remain as aerodynamic as possible for the duration of the run.

The members of the U.S. Olympic Bobsled and Skeleton teams look as if they have just walked out of a photo shoot for Muscle & Fitness magazine, or stepped off the 100-meter medal podium at the track and field world championships. These guys and gals are jacked. They are serious about their training and every bit as strong and fast as they look… and then some.

"Explosive power training is at the core of how our elite athletes prepare for bobsled and skeleton competitions,” says Darrin Steele, CEO of the U.S. Bobsled and Skeleton Federation. “They need to accelerate heavy sleds from a dead stop to full speed in less than 40 meters—faster than anyone else in the world. That requires world-class levels of speed, strength, and explosiveness. You need all three to make the U.S. team… There are no shortcuts."

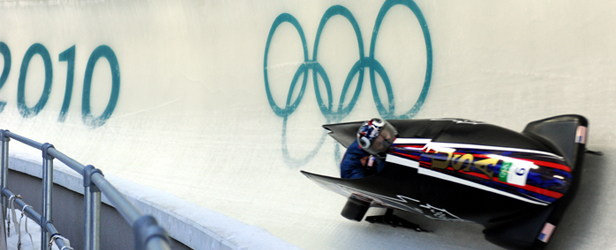

Bobsled is a fast winter sport where two- or four-person teams compete for the quickest times sliding down an ice track at more than 80 mph. The USA-1 four-man team captured gold at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Canada. In 2012, Team USA also captured gold in both two-man and four-man bobsled events at the World Championships.

Former U.S. Olympic Committee strength and conditioning coordinator Jason Hartman says that power development lies at the heart of bobsled and skeleton training. "Everything a bobsled and skeleton athlete does in training is geared towards speed and power development,” he says. “The foundation for building a powerful athlete lies in building strong hips and legs through back squats, front squats, and deadlifts. While we never abandon strength development, sprints, Olympic weightlifting exercises, and weighted and unweighted jumps are the staple movements that best develop the specific qualities necessary for success in these two sports. Success does not always follow the strongest or fastest athlete, but does reward the most powerful."

Pound-for-pound, 2012 world skeleton champion Katie Uhlaender could be one of the most powerful female athletes on earth. She could also be the poster girl for any Olympic sport, and may indeed become both a winter and summer Olympian (we’ll get to that later). She first competed in skeleton at the age of 18—fresh out of high school, winning both the junior nationals and national championship in 2003. As the child of a Major League baseball player and ski instructor, competitive sports were a natural part of her childhood. At 5-foot-4 and 135 rock-solid pounds, she came into the sport with a diverse athletic background—participating in high school track (100 and 300 hurdles, relays, and shot put), powerlifting, and competitive skiing, honed during her childhood years split between Texas and Colorado. In nine years as a Team USA member, she has continued to improve speed and strength through a steady regimen of squats, Olympic lifting, and sprinting four to five days a week, plus work on the skeleton track almost daily in-season. Since 2007, she has won three bronze medals, a silver medal, and finally in 2012, a gold medal at the World Championships.

2012 World Skeleton Champion Katie Uhlaender has been competing in the single-person sport of skeleton since 2003. She trains multiple times a day to develop the levels of speed and strength required for the sport.

“My training has evolved over the years, and today I spend 20 to 30 hours a week training strength and conditioning. Plus, typically we slide five days a week in-season,” she says.

Uhlaender cycles her training and intensity and changes programs every couple of months to guard against overtraining. Her current speed-strength program has her doing Olympic lift variations and medicine ball work several times a day, six days a week, based on Bulgarian training methods. She changes the loading from workout to workout, often going by the “feel” of the weights that day, and she uses bands for recovery work, stretching, and in everyday training—something that became more necessary when recovering from hip surgery and later when recovering from a rebuilt knee cap (from an injury she suffered while snowmobiling).

A typical day of training might include sprints in the morning followed by variations of the snatch. The session after lunch might include medicine ball work and clean-and- jerks. Then, the evening session might focus on more medicine ball work, squats, and jerks/presses.

“Probably the single most important exercise for skeleton, in my opinion, is the power clean,” she says. “It strengthens the hips for the push, which is done in a bent-over position.” She adds that squats and snatches are great for building explosive power at the start.

When you add in sliding work on the sled five days a week in-season, it makes for a demanding schedule. To recover, Uhlaender focuses heavily on her nutrition—eating every three hours, taking amino acids, and making her own protein powder from all natural ingredients. She takes the month of March off after the end of the sliding season, and then starts the cycle over again as a member of Team USA.

Not content with being a Winter Olympian and skeleton world champion, Uhlaender is also now focusing her efforts on perfecting the snatch and clean-and-jerk to vie for a slot on the 2016 U.S. Olympic Weightlifting team.

“Probably the single most important exercise for skeleton, in my opinion, is the power clean,” Uhlaender says. “It strengthens the hips for the push, which is done in a bent-over position.” Not content with being a Winter Olympian and skeleton world champion, Uhlaender is also training to make the 2016 U.S. Olympic Weightlifting team.

Another top athlete training hard for USA sliding gold is 2012 world bobsled champion Steve Langton of Massachusetts. The 29-year-old served as brakeman for pilot Steven Holcomb in both the two- and four-man gold medal-winning sleds at the 2012 World Championships (the first time the U.S. captured both top spots in a single year). He also won the first world “push” championship, a new competition for brakemen, and owns a slew of world cup medals after only a few years in the sport. Needless to say, he is a veritable rising star.

Langton came to bobsled with a background in track and field. A year after graduating from Northeastern University, where he ran track, Langton was looking for an opportunity to continue to compete athletically. He contacted USA Bobsled and was invited to tryout through a series of combine tests. He made the team and will be a chief component in Team USA’s medal hopes at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

“Upright speed is the biggest measure of whether you have potential in the sport,” Langton says. He builds that through intense training sessions in the weight room, sprints or low velocity running five days a week, and pushing the Prowler®.

Like Uhlaender, Langton cycles his training to peak for the competitive season through the end of February. He takes a few weeks off after the season ends, and then begins the ramp-up all over again in March.

Heavy weight training sessions are conducted Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The Monday and Friday workouts consist of back squats and front squats, single-leg auxiliary work, and upper body pressing (bench press, inclines, or regular presses). In preseason training, he’ll work squats in sets of up to 20 repetitions, and then scale back intensity levels to around 70-75% every fourth week to deload. “The high repetitions early in the season help build work capacity to get you through the training workload later in the season,” he says.

Wednesday is a “pull” day, with a variety of power cleans from the floor, hang cleans, and supplementary pulling work. Langton also includes box jumps and glute ham raises twice a week to keep his hamstrings well-conditioned. “Hamstring injuries in bobsled, or any running sport, are common,” he says. “Glute ham raises help you stay healthy and guard against injury because the contraction is so great.”

As the competition season nears, Langton’s repetitions drop, his weights increase, and he shifts to a three-week cycle: two heavy weeks of training followed by a deload week.

He also sprints twice a week in the offseason—either Monday and Friday or Monday and Wednesday. Monday is usually an “acceleration day”—running upright at top speed for distances of 15 to 30 meters. The second sprint day of the week is a “max speed day,” where he runs 60- to 100-meter sprints all-out. He also includes hill sprints for overspeed work. Typical volume on max speed days might be eight 100-meter sprints with a two-minute rest between sprints.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, he does low velocity 100-meter sprints for active recovery (on grass when possible) at about 50- to 60-percent top speed. His preseason daily volume is about 1,000 meters on these active recovery days, decreasing as he enters the competition season.

Brakeman, Steven Langton, (left) and Pilot, Steven Holcomb, (right) share the stage after winning the 2012 World Championships in two-man bobsled. Langton came to bobsled with a background as a college track and field athlete, and his weekly training consists of four to five days of sprinting, three days of heavy weight training, and Saturday sessions pushing the Prowler®.

Saturdays are reserved for pushing the Prowler® with heavy weights, and he starts working with the Prowler® at the beginning of the preseason. “It’s a great piece of equipment,” Langton says. “I bought one of these for my house, and even my parents push it to get a workout.” He has been using the Prowler® once a week since 2009. After a dynamic warm-up, he will push the weighted sled for a run of 30 meters, then turn around and push it back to the starting point. He decreases the amount of weight used with each lap.

Provided he remains healthy over the coming year, Langton will be a serious contender for Olympic gold in both the two-man and four-man bobsled events in Sochi. In turn, both Langton and Uhlaender will compete alongside the likes of summer Olympian Lolo Jones in sliding World Cup events and their respective World Championships in 2013.

Power athletes who think they have what it takes to make the U.S. team in skeleton and bobsled can attend a combine in 2013. More information is available at #

2 Comments