This article is based on the concepts explained in my Unf*ck Your Program course. You can check out the course or contact me for coaching help by clicking here!

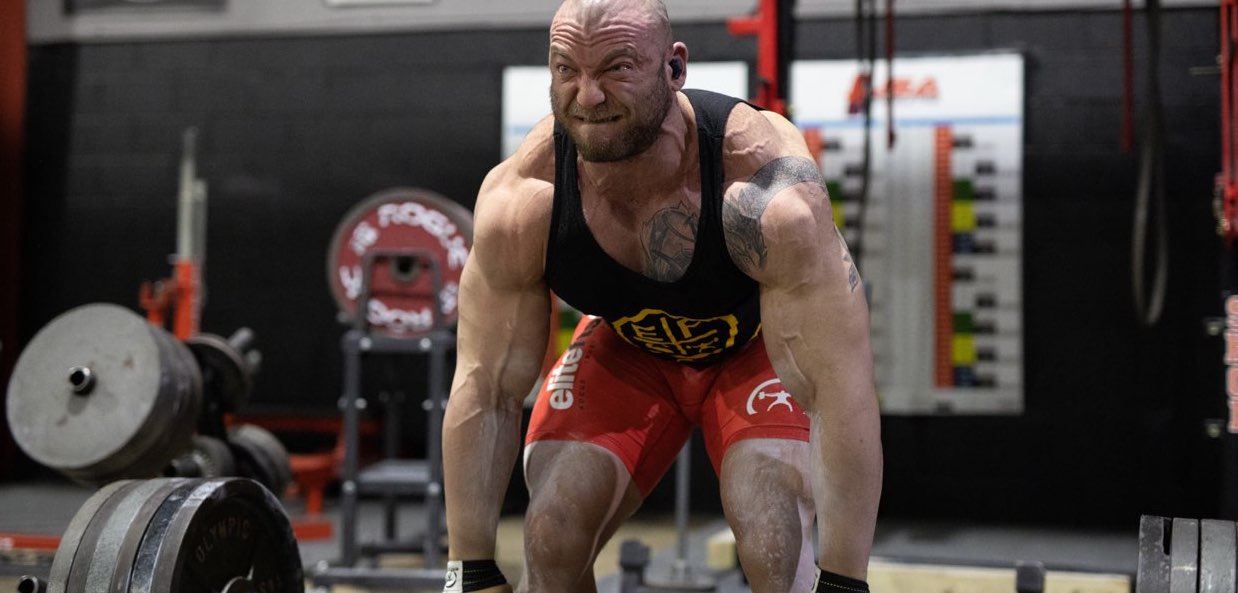

Yesterday, I posted a video on Instagram showing the aftermath of the brutal superset Justin Harris had programmed for me:

- Leg extension, 20 reps

- Safety bar squat, 10 reps

Both to failure with no more than 10 seconds rest between movements, for three total supersets. It was…. Interesting. In a very, very sucky way.

There was an interesting comment posted, too, by @hiimscottcooper:

But is it worth the risk of injury when you could just squat first and leg press afterwards? Not sure if the stimulus to fatigue ratio makes sense over a traditional one after the other.

Now, I gave Scott a bit of a hard time for the phrase “stimulus to fatigue ratio,” because in my very strong opinion, if you’re concerned about working too hard, you’re very misguided. Training hard is the cornerstone of success – as long as you’re able to do so safely and progressively.

(Besides, the whole idea of a “stimulus to fatigue ratio” is pretty nonsensical. Pinky-up dumbbell curls are essentially zero fatigue, so if you’re going by that ratio, they’re the best movement you can do in the gym. Clearly, then, the hypothetical ratio is not a useful measure of anything.)

However, Scott raised a good point in a followup comment, asking about the tradeoff between training harder and training more frequently:

At some point there's a trade-off with that much relative intensity where I'd rather train legs again in a few days rather than blow everything in once session/week.

That’s a much more nuanced point, and it’s one worth looking into. After all, we know from a good amount of research that higher frequency training tends to produce better results in terms of strength, and possibly size as well. However, the idea of “relative intensity” in this context isn’t quite so straightforward.

Intensity Defined

If you’ve enrolled in my Unf*ck Your Program course, you know that in the strength world, intensity is defined as a percentage of your 1-rep maximum. For example, if your best squat is 400, and you’re doing sets with 300, then you’re training at 75% intensity. This measure is completely independent from the idea of effort (which is more typically measured using RPEs or RIRs).

That’s a useful definition in strength terms, because a very well-established body of academic literature shows that periodizing volume and intensity as a percentage of 1RM produces long-term strength gains.

However, the same does not hold in a bodybuilding context. If your primary goal is muscular growth, then intensity is better equated with effort. That’s because muscle growth tends to occur most when training close to or at muscular failure – regardless of the absolute load on the bar. In other words, if you’re training for strength, there’s a big difference between performing 5 sets of 5 with 75% 1RM and performing 3 sets of 8 with 65% 1RM. For muscle growth, there’s not so much of a difference (assuming that your level of effort is equally high in both loading schemes).

Applying The Concept

Now, I want to be clear on that last statement: there’s not so much of a difference between 75%x5x5 and 65%x3x8 in terms of muscular growth in the short term. The long term is more complicated.

Fair warning: the rest of this article isn’t supported by academic evidence that I’m aware of. It’s based on my own experiences and observations, so take them for what you will.

In the long term, I believe that considering absolute strength is a crucial factor when programming for muscular growth. Let’s look at two different scenarios to understand why this might be the case.

- Guy #1 is 5’8, 170 pounds, and has a 1RM squat of 400.

- Guy #2 is 5’8, 240 pounds, and has a 1RM squat of 800 (that’s me).

If guy #1 were to take 75% 1RM (300 pounds) and squat to failure for, say, 6-8 reps, he’d probably be pretty sore for a day or two, but he’d also be able to come back in a week and do 305-310 pounds for the same 6-8 reps before hitting failure.

If I squatted 75% 1RM – 600 pounds – for a set to failure, I wouldn’t be able to walk for a day or two and probably would stand a pretty good chance of getting hurt if I attempted to do 610 for the same number of reps the following week.

But what if instead I supersetted leg extension and squats? Well, then I could use significantly less weight (say, 60% 1RM instead of 75%) and still hit failure on squats without potentially crippling myself. This scenario, I believe, is where you get the idea of bodybuilders taking a light weight and trying to make it feel heavy; and it’s also why you see so few pro bodybuilders lifting insane amounts of weight on a regular basis.

However, this is only applicable to guys with very advanced levels of strength. If guy #1 were to try that superset and use 250 pounds on squats, I personally don’t believe he would be using enough absolute weight to trigger as much muscle growth as he would using straight sets of 300 pounds.

Furthermore, guy #1 would probably not be able to come back the week after supersetting squats and extensions and be able to hit that 310, because he hasn’t had enough practice with training in those higher percentage ranges. Guy #2 almost certainly has been training enough to be proficient at virtually any percentage of 1RM without needing so much practice. Therefore, I believe the benefits of higher-frequency training are relatively lower for guy #2. If true, this would explain why you see so many pros (virtually all pros) training with once-per-week bro splits despite research supporting higher frequency training.

Again, there is no scientific evidence supporting this claim. It’s based on my experience and opinion. It seems virtually impossible to recruit enough professional lifters to perform a good study on the topic, anyway.

Takeaways

So, what does this mean for you? Simple:

- If you’re at anything less than a very advanced level of strength, focus on getting stronger at the basic movements by manipulating volume, frequency, and intensity as explained in UYP, regardless of whether your primary goal is to get stronger or get bigger

- If you’re at a very advanced level of strength already, and your primary goal is muscle growth, you’d probably benefit from traditional bodybuilding approaches like supersets, frequent movement rotation, bro splits, and so on

What comprises a “very advanced” level of strength? I can’t answer that for you – it’s entirely individual. Some guys genetically gifted for building muscle might do just fine on a diet of 400-pound squats, but I believe they are relatively few and far between. If I were to throw at some numbers, I’d say a 600-pound squat, 500 bench, and 700 deadlift would constitute “enough” strength in a bodybuilding context, regardless of bodyweight.

The more important takeaway is this: don’t get hung up on nuances like “stimulus to fatigue” or anything else. Focus on the basics: training and eating hard. Put in just enough thought to make progress – for most people, that means periodizing your training and making small changes as explained in UYP. Anything else is likely a distraction.

Been on TRT for 2 years. Now 5'8" 165-170 with one row of abs with genetics of skinny parents. Don't know my 1 rep max, but DL 360 for 8, bench 190 for 8, sq 300 for 8.

I do accessories of row, chin, OHP with some R delt, calves, tri/bi.

I follow some of your UYP weekly splits with major lifts being first and foremost.

Would like to be 175-185 with abs. No competing.

I think I screwed myself by no taking advantage of noob gains. I do have extra T cyp and have been doing TRT dose cyp and 140mg tren for 3 weeks. Have difficult time eating junk and hard to eat enough clean calories.

Love your progress over the years.

Wed: Squat 3-4 x8 at 300

Row 3-4x6-10 at 175

rear delts, bi/tri some abs/back ext (isolations are intuitive)

Fri: Bench 3-4x6-8 at 190

Chin +50-60 lbs 4x 4-6

push ups, planks

Sun: DL 5x3 at 355

OHP 3-4x8 at 155

close grip bench or chin body wt, bi/tri, abs.