The Burden of “Everything”

We start this journey across the exercise and sports performance professions with the coach and end it with the physiologist, because both share the burden of “everything.” In a sense, they embody the concept of interdisciplinarity itself. In articles and books about coaching, a common definition is that the coach is responsible for promoting the athlete’s (or exercise practitioner’s) performance, health, and emotional well-being, among other things (Jeffreys 2014).

Jeffrey (2014) claims, “It is unlikely that coaching can be completely mastered from the viewpoint of a single discipline.” (2014) For many authors, though, it is up to the coach to acquire the knowledge from the various disciplines and integrate them. Most authors agree that published scientific evidence is not enough of a tool for a coach in his program design and delivery.

But this is not interdisciplinary work. At best, this is multi-disciplinary knowledge and highly developed skills in knowledge integration. Interdisciplinary work, by definition, involves professionals from different fields of knowledge collaborating towards a common goal. In this specific case, this is athletic performance or health.

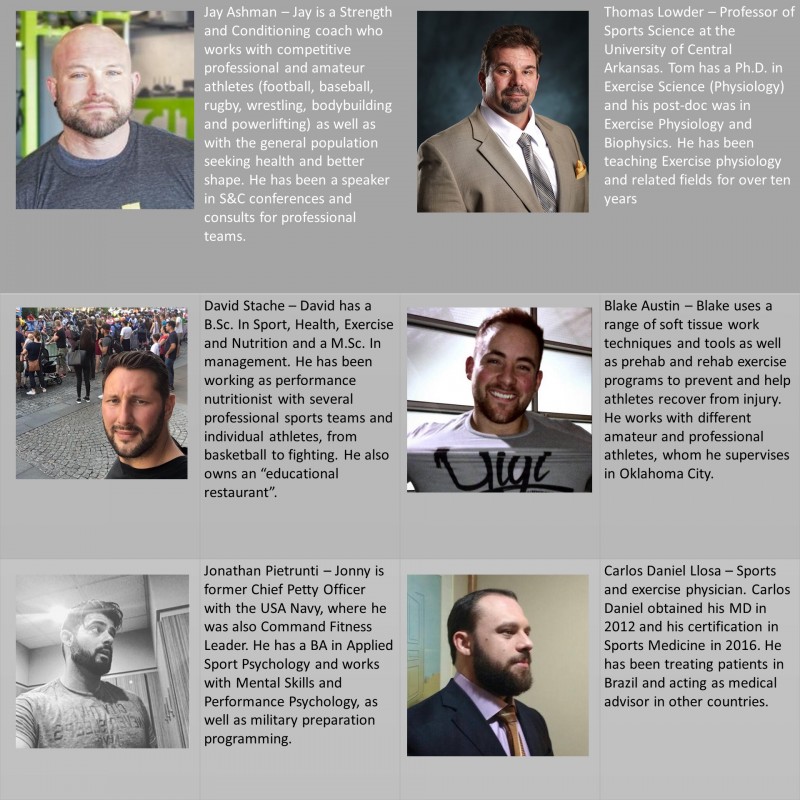

PART 1: All Together Now — Meet the Disciplines and Our Hosts

Not many institutional environments promote interdisciplinary collaboration in exercise and sports performance.

In the end, the burden falls heavily on the strength and conditioning coach, from whom a broad knowledge of different scientific disciplines is expected, as well as the mastery of techniques derived from different professional fields and, of course, the creativity to go beyond evidence-based research.

Criticism towards regulating bodies that should assess knowledge and skills and offer certifications has been growing in recent years.

How do coaches manage to work, under these apparently chaotic conditions? There is not much published work on the issue. Most evidence comes from collegiate or Olympic sports, where, still, coaches report that integrating information and making decisions is still pretty much their business. There are a few structured programs, and information from them shows that we’re still crawling concerning an effective interdisciplinary work structure. Much of the most relevant communication is informal and relies on coaches’ initiative (Rogerson & Strean 2006).

While most coaches express the desire to have “at least” a physical therapist working with them, since injury is the major concern in this scenario, this is a reality for few (Dijkstra et al 2014).

One would think that now is the time to bring sports management in and get their decision-makers to incorporate the needs of coaches and athletes. They are not deaf to such cries, but most agree there is a long way to go here (Burwitz et al 1994, Costa 2005, Doherty 2012).

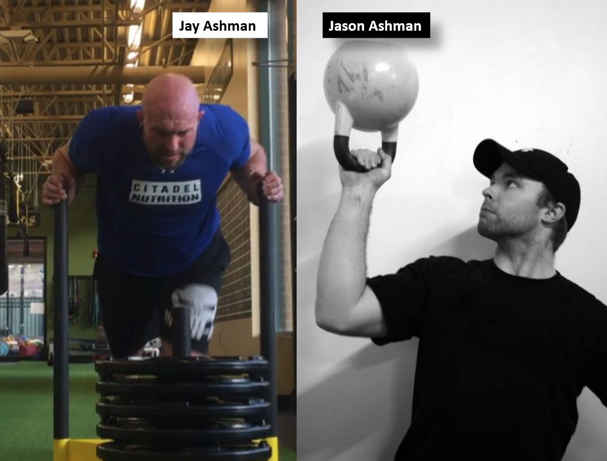

In this series, our “host” is coach Jay Ashman. I have also interviewed five collegiate coaches, three of whom preferred to remain anonymous, and obtained relevant feedback concerning the Canadian scene from Jason Ashman. Jay Ashman’s full interview can be read here.

From the Ground Up: Physical Education

Jay has been a trainer since the 1990’s. Unlike many others in the coaching world, he has extensive experience with kids. Maybe this is why, of all the coaches discussing knowledge integration, he was the one to point out the structural problem way behind: physical education teachers are not given the chance to develop a truly integrative content.

“There is a good chance most of us will never be in contact with a physical education teacher while training athletes. This is why I feel that the profession of PE teaching needs to be given its proper respect and expanded from a glorified coach who plays games with kids to teaching about health, nutrition, and movement, as well as sports skills. Think about how that entire profession would change if we enabled PE teachers to be actual teachers as well as coaches.”

Yes, think about what would happen if we, as a society, could regard movement, exercise, and sport as things where many different disciplines overlapped. Or if we could move even further back and bring in the knowledge acquired by developmental psychologists about motor learning into a physical education plan, sports talent screening, and a blueprint for an active and healthy adulthood. Sounds surreal, doesn’t it? It's because we have been blocked in our ability to see that what psychologists are studying about toddlers’ movement skills reflects on future old-age stability, or what paleontologists tell us about research into the evolution of the human grip can inform us on such wide range of topics as grip training for athletes and general health among the elderly. A brave new world, and probably a much healthier one, too.

MORE: Old School PE — Valuable Today?

Talking about the interplay of performance-related profession, Jay points out that:

“(…) can all benefit from the other. In the preparation side, it starts with physical education. During that time it would be ideal to teach about sports nutrition – which, in my opinion, would be an excellent addition to a gym class in school rather than health class. Teaching about proper nutrition in the context of PE class would help reinforce ideals of proper eating, as per physical fitness.”

We will not exist without the others, period.

Says Jay.

Having established that all the exercise and sports-related field depend on each other, does that materialize in actual professional interaction? Yes, it does, but mostly as result of a personal initiative.

One of the things that make it easier to collaborate is having previously worked closely with allied-fields professionals. This was Jay’s case:

“In NYC/Long Island I was also a PTA. During that time, I had first-hand experience working with their athletes assisting with rehab, and the doctors that employed me also graciously allowed me to use their facility (they had weights and machines) to train post-rehab clients. I worked with their baseball players, softball players, cops, and normal people who wanted to be stronger.”

His experience with different populations allowed him to have enough understanding about nutrition as to provide guidance to his clients. However, as he points out:

“I am not a clinician, I am a strength coach. Those are two distinctly different lines of work.”

He keeps a list of trusted colleagues in the clinical fields that he can refer his athletes and clients to when necessary.

The Institutional Sphere

I interviewed five collegiate coaches. Since three of them preferred to remain anonymous, the information they provided will be limited to general aspects of their activity. Their occupations are:

- Athletic Director

- Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach

- Sports Performance Coach/Adjunct Professor in Exercise Science

- Graduate Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach

- Head Strength and Conditioning Coach

They’ve been long in the field. Three of them have been coaches for longer than 15 years and two of them have been coaches for more than six years. Four of them, like Jay, were competitive athletes before they became coaches, which gives them the benefit of understanding exercise and performance from both sides. Four of them were or are part of multi-disciplinary teams. What is surprising (and a little sad), though, is that for each of the chief exercise or performance-related fields, only two collegiate coaches reported having had collaboration with sports physicians, physical therapists, sports psychologists, or sports nutritionists. They reported being able to do interdisciplinary work with “someone.” The “someones” listed were:

- Head Sport Coach and Athletic Trainer

- ATC's, Other Coaches, Sports Coaches

- Chiropractor and Massage Therapist

- Athletic Trainer

On the list is no sports physician, no sports psychologist, no actual physical therapist, and no sports nutritionist (although one reported “daily interaction with sports medicine staff.”).

One of the respondents expressed what is actually the view still held by most organizations and even regulating or certifying bodies:

“However, as collegiate strength and conditioning coaches, it is our responsibility to be proficient enough to design and implement programs without any inter-disciplinary input. If we can't do that, then we aren't suited for the job. Nevertheless, the most successful strength coaches are those whose door is always open, welcoming input. (…) The smaller the school, the smaller the budget, the smaller the staff. As a result, it becomes difficult to design varied programs suited to the individual needs of distinct positions within a sport, such as track and field, which comprises disparate events. Regardless, as one matures as a coach, he or she is able to carve out the time to design positional or event-based programs, and implement them without additional help.”

When they were asked to list, in order of priority, which allied field professional they would choose to work with, if they could, there was no consensus. As first choice, they listed:

- Lifting Coaches

- Nutritionists

- Sports Coaches

- Strength and Conditioning Coaches

- Sports Psychologists

When asked about their relationship with the allied field professionals, the same discrepancy was observed. From “non-existent” to “very good”, there was a little of everything. One common thread was a more difficult interaction with sports physicians, in contrast with the “openness” and generosity from the physical therapists and sports psychologists.

One of the respondents pointed out that, “The relationship between strength and conditioning professionals and sports nutritionists is in the beginning stages of development, but continual growth looks positive.”

Only one of the respondents was highly integrated into research. The proverbial “gap between science and practice” may not have been properly bridged, after all.

The Coffee Break (or the Bar, Your Choice)

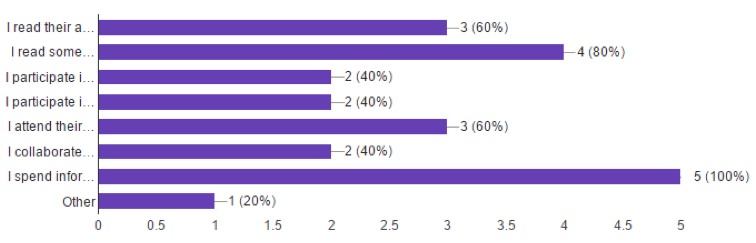

When asked about what interactive activities coaches engaged in with their allied field colleagues, informal interaction prevailed. The options were:

- I read their academic journals.

- I read some newsletters and follow some websites.

- I participate in digital discussion groups.

- I participate in on-ground discussion groups in my campus.

- I attend their conferences.

- I collaborate in their research.

- I spend informal time with professionals from allied fields (coffee breaks, parties, bars, other social situations).

And the result is:

This is consistent with the findings of Rogerson and Strean (2006) and doesn’t indicate, per se, neither high or low interdisciplinary work structure. It does indicate that coaches are open and eager to interact.

“The communication is clear from my point of view. I have yet to have an issue with a specialist when I reached out to them for information or help. It has been my experience that the assistance tends to pay it forward. I think that is part of the perks of being a part of that field where others are willing to communicate ideas and protocols openly for the sake of education and helping out athletes.” (Jay Ashman)

Touchy Subject: Certifications

As Jay was finishing his interview for this article, he shared some views publicly and was joined by many coaches. Most of them were deeply dissatisfied with the major certifications. Contributions from coach Jason Ashman (yes, precisely the same birth name), from Canada, helped shed some light on the issue.

Jay Ashman explained:

“Originally I took an AAAI/ISMA cert to get my foot in the door. That test was written and practical. Both parts were done at a class I went to specifically for this certification.

I have an ISSA S&C certification. The test was a few parts, one of which was an essay and one was a video practical exam. I chose this certification because ISSA is well respected. I am working towards the NASM-CPT right now so I can use that to get their PES.

I am planning a future trip to earn the CPPS, which is an incredible certification and in my opinion is one of the best in the business for what I do.

Even with all that paper education under my belt, my best teacher was time, opening books, learning from mistakes, attending seminars, calling my peers for advice, listening to those better than me, and doing all of them repeatedly.”

Jason Ashman elaborated on the value of each certification:

“I have a CSCS, but I also have a degree in kinesiology. It is better than a lot of the certs out there — I'd still prefer a CSCS to most of the other certs available for athletic training, which are increasingly common these days.

The certification I actually value is my Certified Exercise Physiologist standing from the Canadian Society of Exercise Physiologists. A kinesiology/exercise science degree is required, you must log 250 hours of supervised internship, then pass a 150-question exam, and a four to five hour practical. The best part is that there is no textbook; the questions can come from essentially anywhere in exercise science. In my practical, I did— amongst other things—an FMS on a university athlete, aerobic testing on an octogenarian, and a full gas-analysis VO2 Max on a middle-aged cyclist.

I learned more from prep for that exam—and got exposed to more graduate-level exercise science texts—than I thought was possible. If memory serves, the fail rate for that cert is somewhere around 75%.

It is Canada's gold standard for certification testing. There are not a lot of us, but we're qualified, and insured, to work with just about everyone, from Olympic and professional athletes to people suffering from chronic conditions (ALS, MS, severe diabetes, Parkinson’s, etc.) and everything in between.

The CSEP-CEP is a requirement for certain jobs working with the military, in academia, in hospitals, and for most jobs working with athletes in the national program. It is also becoming the minimum standard for working in collegiate sport, although that standard is slow [in moving forward].

It is not mandatory. In fact, most of Canada's personal training workforce is dominated by the Canadian Fitness Professionals Certifications set, which is owned by Goodlife Fitness, the company that controls a high proportion of the industry up here. They churn out hundreds of certs per month to individuals, many of whom are ill-qualified to see even the most basic of clients."

Bottom Line

A lot is expected from coaches. That reflects on institutional and societal demands, as well as in demanding certifications that may or may not be matched by higher education curricula. What is disturbing, though, is that the high pressure or chaotic factors in this scenario reflect on coaches’ health. Recent research suggests a high vulnerability of coaches to psychosocial stress (Kelley & Gill 1993, Tashman et al 2010, Fletcher & Scott 2010, Knight et at 2013).

After all that was presented here, it is clear that interdisciplinarity is valued, expected, but not structured into coaches’ work or educational environment. This social expectation becomes, therefore, an individual responsibility for the coach. That is never a good equation.

How we will solve it, as a society, remains to be seen.

Acknowledgements

Brijesh Patel, Head Strength and Conditioning Coach from Quinnipiac University; Keith Scruggs, PhD Student, Adjunct Professor, and Sports Performance Coach at the University of South Carolina; Jay Ashman (see above), Jason Ashman, Kinesiologist/Certified Exercise Physiologist, Canada.

References

- Burwitz, Les, Phil M. Moore, and David M. Wilkinson. "Future directions for performance‐related sports science research: An interdisciplinary approach." Journal of sports sciences 12.1 (1994): 93-109.

- Costa, Carla A. "The status and future of sport management: A Delphi study." Journal of Sport Management 19.2 (2005): 117-142.

- Dijkstra, H. Paul, et al. "Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model." British journal of sports medicine 48.7 (2014): 523-531.

- Doherty, Alison. "“It takes a village:” Interdisciplinary research for sport management." Journal of Sport Management 27.1 (2012): 1-10.

- Fletcher, David, and Michael Scott. "Psychological stress in sports coaches: A review of concepts, research, and practice." Journal of sports sciences 28.2 (2010): 127-137.

- Jeffreys, Ian. "The Five Minds of the Modern Strength and Conditioning Coach: The Challenges for Professional Development." Strength & Conditioning Journal 36.1 (2014): 2-8.

- Kelley, Betty C., and Diane L. Gill. "An examination of personal/situational variables, stress appraisal, and burnout in collegiate teacher-coaches." Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 64.1 (1993): 94-102.

- Knight, Camilla J., et al. "Personal and situational factors influencing coaches’ perceptions of stress." Journal of sports sciences 31.10 (2013): 1054-1063.

- Rogerson, Lisa & Strean, W.B. "Examining Collaboration on Interdisciplinary Sport Science Teams." University of Alberta, 2006

- Tashman, Lauren S., Gershon Tenenbaum, and Robert Eklund. "The effect of perceived stress on the relationship between perfectionism and burnout in coaches." Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 23.2 (2010): 195-212.