A few days ago, I was on a call with a friend who has an autistic son. I'm always ferociously writing notes on these calls hoping I can connect data points to provide some form of outside perspective clarity. Typically, a few days later, I can process all the information given, spot common threads, and create a plausible action plan. In review, a common thread in this conversation was the father's connection with his fourteen-year-old son or lack thereof—"I'm having a hard time connecting with him—he's always in another world."

I want to share how I'd approach the situation to help the father better connect with his son while giving you some other similar cases to explore this Connect-By-Entering-Their-World concept.

Note: The ideas found in this article are based on my experiences successfully working with autistic children and adults. I measure success via a decreased amount of harmful behavior to self or others; meeting or exceeding home, personal, or school goals; a newfound relationship between the child and at least someone else, and a decreased reliance on a fictitious world.

Enter Their World?

So where does a child go when their physical world is too loud or quiet, bright or dim, uses jargon that makes no sense, and is full of people speaking a complicated language who don't seem to understand their needs fully?

MORE: A Program Progression for an Alternative Use of Basketballs and Volleyballs

A child creates their own world and flees. Their world is furnished with safety, logic, and acceptance. Additionally, the environment is non-invasive, peaceful, and nourishes their hijacked senses.

In my experience, these worlds are commonly fictitious or have fictitious components. These places highly vary per child, but I'm most familiar with reliance on stuffed animals, cartoons, books, and video games. Typically, the line between reality and fiction blur.

Where Do You Enter?

Revisiting the father and son I was talking about earlier, the child has been unruly at home for the past couple of months and has lost privileges at school. He's an athlete with aspirations of one day playing for the NFL, trains at home and school, and is wildly knowledgable about everything baseball. Otherwise, the child is playing video games, and it's what he resorts to after school, on the weekends, and for most of his free time. It's also the one thing that, if taken away (as a consequence based on behavior), creates hell in the household for everyone.

Although the dad is part of his practices, trains with him at home, and makes baseball-everything accessible, he still feels he's not connecting with his son. The dad admits that when his son mentions video games (it's mainly what his son wants to talk about when he talks), he can't follow or engage since it's something he knows nothing about or has little interest in learning more.

Enter Here

As you can recall from above, the child has already tried to invite the dad per conversation, but the dad was reluctant to accept the invitation (or at least didn't see it as an invitation). The next time the child brings up something related to video games, the dad could make an honest attempt to engage and learn the features his son wants to share. As I'm sure the dad is buying the games, he can do some surface-level research on a few of the games and ask his son questions. The dad could go a step further and carve out some time weekly to play video games with his son—every Thursday after lifting and dinner, for example.

Stuffed Animals, Zippy and Zena

A past client of mine traveled to school and extracurricular events with a few of his favorite stuffed animals, Zippy and Zena. His parents decided that for training (a new endeavor for the child), they'd remove the stuffed animals from his travel routine. I'm assuming they were looking for a way to minimize reliance on the stuffed animals, so they exchanged the stuff animals for a new activity. The child scrambled into the facility, screaming and distraught for his training session. Despite a schedule and calm environment awaiting him, he wanted nothing with the planned activities or me.

"I'm having a hard time connecting with him—he's always in another world."

After a few minutes of observing the child crying and thrashing his body onto the ground, I asked the parents what his day looked like and if anything unusual had happened. "Well, Zippy and Zena are at home." Incorrectly assuming Zippy and Zena were pets or siblings of the child, Zippy and Zena were the child's stuffed animals he closely associated with and took everywhere.

Although severing reliance on two stuffed animals sounds like a practical growing-up solution the child could benefit from, now was not the time for him to experience this lesson. Placed in a new environment with new demands and a new face without Zippy and Zena, the child was non-responsive, uninterested, and scared.

Rather than moving forward with the session, permanently giving the child the option to associate the gym with harsh demands, we ended there and rescheduled for the following day, permitting Zippy and Zena to tag along.

Enter Here

The child skipped into the facility carrying Zippy and Zena the following day. He was calm, receptive, and smiling. Zippy and Zena's presence eased him into a new environment with new demands. I welcomed them as I did the child. What the child did, they did, and if the activity didn't include them, they watched. Having them around allowed my prompts and cues to be repeated and reinforced because after the child completed the drill or exercise, he became Zippy and Zena's coach. If he hadn't paid attention and listened closely, Zippy and Zena would be lost and unable to complete the task.

Around week three, Zippy and Zena's inclusion began to lessen slightly. Now they were joining us in specific activities and watching more. Around week five, they were sitting with mom in the waiting area, and during free time they could be visited. At week six, they were in the car, patiently waiting to hear all about the training session. The child's dependency had naturally lessened throughout the six-week period—ultimately what the parents were trying to accomplish, but in an alternative way.

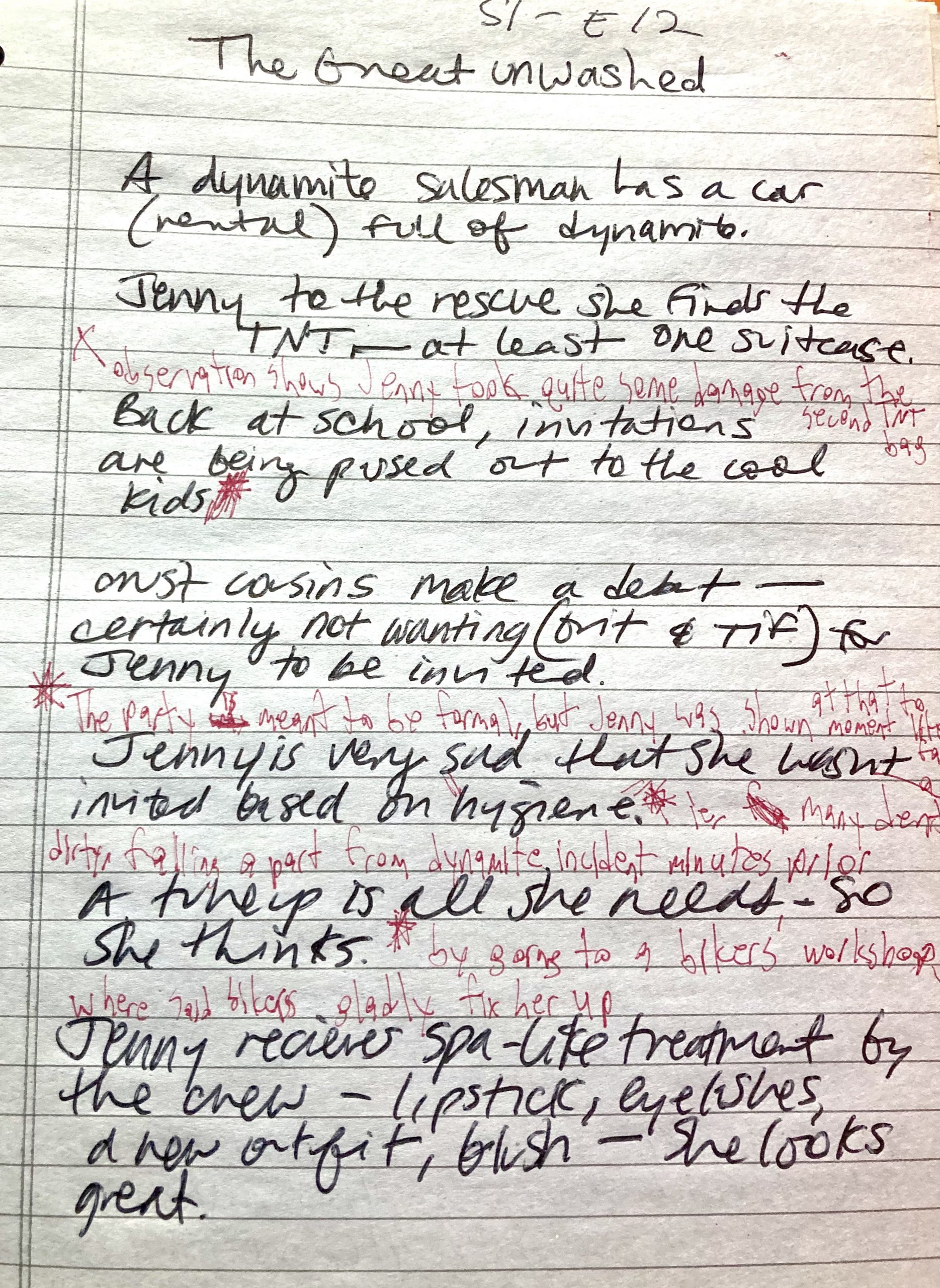

My Life As A Teenage Robot

Years ago, maybe when Blaine was 14 or 15, I had a similar situation unfold like the father above. I felt Blaine and I were disconnected even though we had six years of training under our belts. Our weekly sessions were becoming laborsome—he was quick to fly off the handle, was in a bad mood that I couldn't dissolve, nor would he be interested in trying anything new.

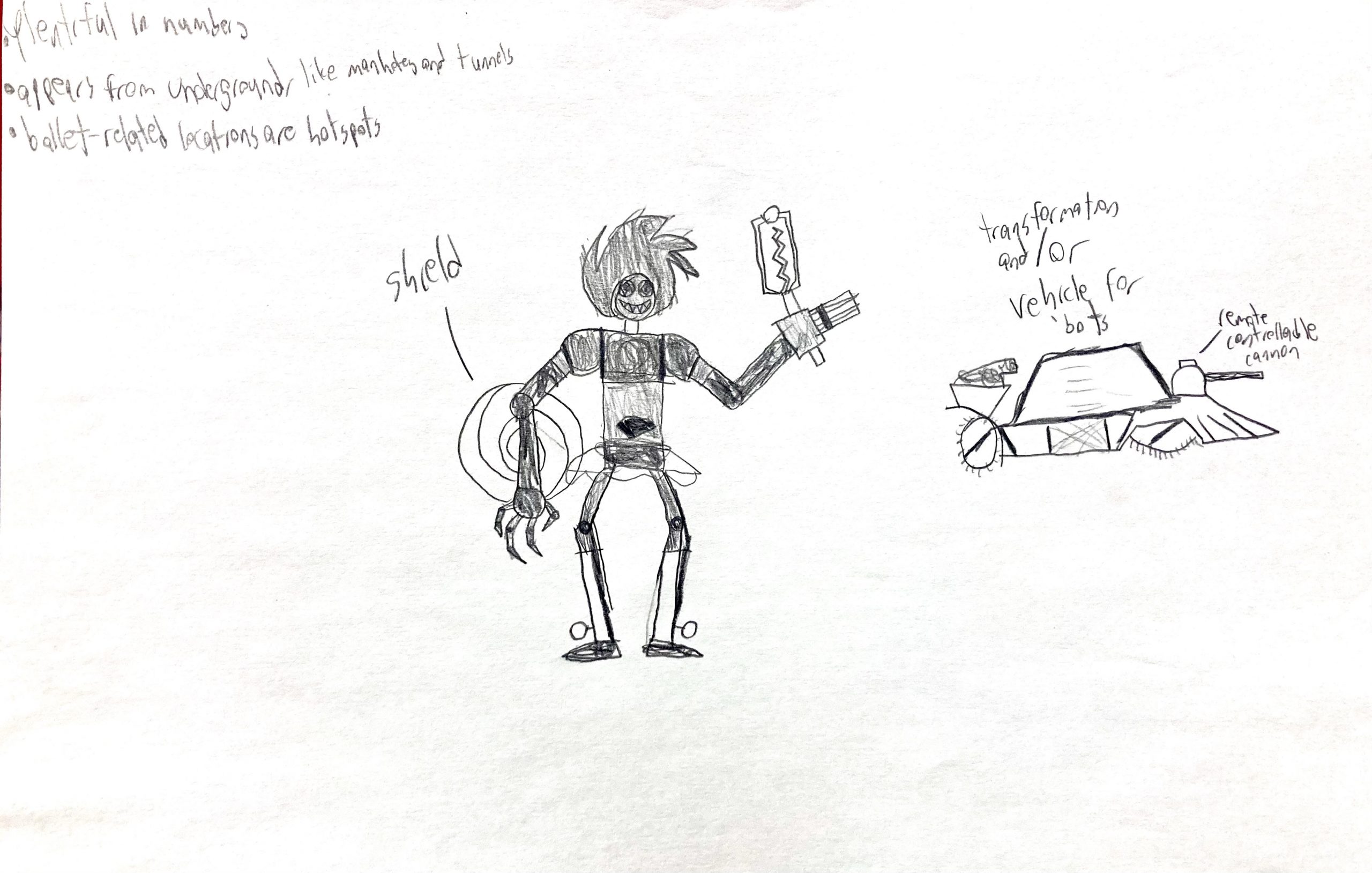

He'd mention a robot with superhuman powers or ask hypothetical questions about an evil entity trying to take over the world when he did talk. I typically shrugged these questions off or tried to change the subject as I had no interest in talking about a robot or something non-sensical.

Enter Here

Then one day, I tried something new—I entered his world. When he mentioned Jenny again (the robot's name), I asked what her age was. Blaine shared every detail imaginable and went on to tell me that he memorizes every episode and how I wouldn't want to know how much he watches each season. I got the sense that he felt she was his friend.

One thing led to another, and before I knew it, Blaine was giving me homework each week. I had to watch an episode weekly, take notes, and then summarize the episode during our next training session. After say six episodes, Blaine quizzed and graded my answers. Some episodes were an hour-long, and if I earned a grade lower than a B, I had to rewatch the episode and test again.

Blaine's behavior while training instantly changed. He was excited for each session! Although there were days he came in after having a bad day at school, any mention of Jenny positively rearranged his behavior. It was like flipping a switch. Training became enjoyable again and he was willing to exert more energy and try new exercises per the newfound connection. The show also served as a way we could discuss people's motives and talk about how we'd resolve a problem (in the show and how that relayed to a problem we may be facing in real life).

We were in this robot world for about three years. Connecting here paid dividends for his physical and emotional development and our relationship. Since then, Blaine has created new worlds, and with each new phase, I'm accepting and enter.

Conclusion

Although the father would likely rather connect with his son by talking about school, making friends, nutrition, football practice, the future, or something about himself, now is not the time. Ultimately, I'd suggest the father lift the unturned stone and show an interest in the video game world his son flees to. How do you think the child will react if his dad shows interest in this one thing? Is it possible the child will let his guard down—possibly trust his dad's motives a little better, and feel accepted when trying to engage in conversation (which is a pretty big deal)? Do you think this will affect his home and school behavior?

It's worth a try.

Understanding and implementing the Connect-By-Entering-Their-World concept with the children and adults I cater to has been life-changing. With the two examples given, a relationship strengthened and had positive implications outside of the fictitious world (which naturally decreased in reliance).

Header image credit: mopic © 123rf.com

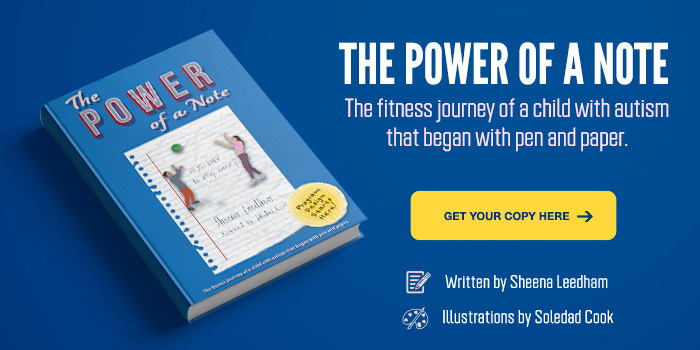

Sheena is a licensed teacher. She earned her bachelor's in health and physical education (with a concentration in recreation administration) and her master's in education (K-6) at Edinboro University. Sheena facilitates and consults Ohio State University’s Nisonger Center programs: Men’s Aspirations, Autism College Experience (ACE), and Postsecondary Linking Advocacy & Navigation (PLAN) in conjunction with Dublin City Schools PATHS programs. Read The Power of a Note, an outreach tool she created to show parents, educators, and coaches how to program design exercise for an autistic child.

1 Comment