Fatigue is an expected experience during exercise. Ordinarily, society is taught to not quit and push through the feeling of being tired. While this does have its time and place, it should be cautiously approached with full understanding of the risks vs rewards.

“Fatigue compensation” is attained when the brain has reached its fatigue threshold. This is a point in time that leads to disrupted breathing patterns, dysfunctional body mechanics, increased sympathetic tone, and a variety of other adverse side effects. Listed below is part one of how to improve your resistance to fatigue compensation.

Understand Movement

Truly understanding movement is a complex task that requires a great amount of motor control, sensory awareness, and congruency. Movement can be learned through various techniques, however, I suggest introducing manual resistance as the primary movement training tool. Manual resistance is simple, effective, and provides two powerful brain paradigms: sustainability and inhibition.

RECENT: Should Pain Be Normal?

Sustainability of muscular tension improves awareness of the concentric, isometric, and eccentric phases of movement. Typically, compensation is seen in the transition phase between the eccentric and concentric periods. However, sustained tension through manual resistance allows the sensation of a smooth, non-compensatory transition. Moreover, sustainability creates facilitation, and facilitation promotes inhibition. The facilitated tone allows proper inhibition of accessory muscles (neck, low back, etc.) through brain adjustments of newly gained stability. Through sustained tone, the brain now has the support it needs without relying on the once-desired accessory muscles.

Manual resistance can be applied to virtually any exercise. Some of the most common are hip clams (clam shells), shoulder internal/external rotation, ankle flexion/dorsiflexion, and overlooked pushing/pulling exercises. During the exercise, the coach has the ability to alter tension, when needed, to sustain the appropriate amount of stiffness. As the exercise continues, the client or athlete will begin to fatigue, this is the essential part of manual resistance. Traditionally, when free weights are used, the client or athlete has to compensate to continue the desired movement. Conversely, a slight deviation in manual pressure allows the client or athlete to continue the motion without the need to compensate. It seems simple enough, but this is critical when movement is being learned and developed. The central nervous system will process this information and transfer it to exercises that are more demanding, difficult, and faster.

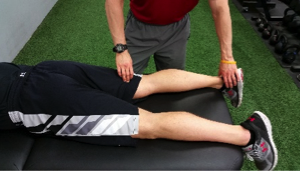

A prone hamstring curl is a great beginner manual resisted exercise. Often, people struggle with maintaining a proper position, let alone strength coupled imbalances in the posterior chain. As always, proper position should be established prior to beginning a strengthening phase. Optimal position can be established through the use of PRI exercises such as the 90/90 Hip Lift with Hemibridge, 90/90 Hip Lift with Balloon, or a Modified All Four Belly Lift. Once position is accomplished, strength needs to be added to the system to maintain this acquired position. The other beneficial element to a manual resisted prone hamstring curl is the client or athlete's restricted visual acuity. They must rely on the sensory and motor system to properly relay neuromuscular information.

Coaching Movement

How do you properly coach and execute this exercise? The coach uses one hand to distribute the correct amount of force, while the other gently taps the client's or athlete's hamstring. The continued stimulus of tapping is a constant reminder to the brain to sustain muscular tension. Without the provocation, you may find a decrease in overall sustainability from poor communication between the muscle and the brain. The coach begins with the first hand on the back of the ankle to appropriately distribute the required pressure. Activate the movement with a brief isometric contraction to show the client or athlete how to develop tension.

RELATED: Troubleshooting Knee Pain While Squatting

Next, they should begin the concentric phase by “pushing through this pressure.” If movement is limited, decrease your pressure. If tension is fluctuating, increase your pressure. The most important phase is going to be the transition from concentric to eccentric. Most clients or athletes will thrive for a transitory moment of relaxation before initiating the eccentric phase. However, this is a representation of the accessory muscles compensating to gain a sense of stability during more advanced exercises. In short, always ensure there is muscular tension during this phase of the movement.

Lastly, control the eccentric phase by “fighting the pressure through a controlled descent.” Continue the eccentric phase and stop just short of full knee extension to help bias the sustained tension prior to beginning the concentric phase. Throughout all of this, the second hand is providing persistent stimulus to the sensory system to maintain tension. This neurological component coupled with the working muscular system allows for plasticity and development of movement to occur.

Whether you are working with an elite athlete or a general population client, manual resistance should be an initial thought to develop quality movement. Learning proper movement in the beginning will set the stage for future success. In part two we will look at the effects respiration has on the central nervous system in appropriately controlling our fatigue compensation.

Brian is an up-and-coming strength and conditioning coach. He is the owner of Functional Training Studio in Charlotte, North Carolina. At a young age, Brian has been training clients for over six years and is always looking at ways to improve his technique. He utilizes positional asymmetries that exist within the body to help clients and athletes improve their function and overall performance capacity. Brian has a degree in exercise science and is a certified strength and conditioning coach through the NSCA. Additionally, he plans to continue his education in 2017 in a doctorate of physical therapy program. For additional questions, Brian can be reached at FTStudio130@gmail.com.