A few months ago I wrote about some of the things that I, along with my coaches Cris Edmonds and John Meadows, did to bring up my back between the 2015 and 2016 contest seasons.

What we did worked well, and I am continuing to implement those techniques, along with a few new ones.

As of the time of this writing, I’m 22 weeks removed from my last contest. If you don’t count the four weeks that we spent deloading a bit, doing some lower intensity work and reverse dieting, I’ve gotten a good four months of off-season training in the bag. The first phase of training was devoted to bringing up my chest and delts with John’s well-known Creeping Death program. Now we’re starting to increase the frequency of my back training from one dedicated session per week to two, one being the normal, heavier base day you see in Mountain Dog programs, and the other being a faster-paced pump session.

Besides the obvious details like volume, sets, reps, intensity techniques, and other things that can be picked up from the program itself, here are some of the things that I’m implementing.

Soft Tissue and Mobility Work

A couple of months ago, I found a great deep tissue massage therapist and have been trying to make it a habit to go there every couple of weeks. I have her go after my lats and upper back (obviously), and also have her work on opening up my pec minor to get me out of an internally rotated posture so I can squeeze harder. She also works on my right trap — it has this nasty tendency to elevate if I’m not careful during my rows and pulldowns, and when it gets right it’s downright distracting.

I also take five to 10 minutes before training to mobilize my lats and thoracic spine on a foam roller. I do a little bit of simple soft tissue on each lat, making sure to go slowly and cover the entire lat, and thoracic extensions for as many reps as it takes to get me opened up. This is usually in the 10-15 rep range, although sometimes I will do more just to give myself a miniature chiropractic adjustment if I can feel there’s something waiting to crack as I’m going. If I skip out on these, I usually find that I get all of my extension from my lumbar spine instead of my thoracic spine, and my lower back gasses much quicker than it should.

During my first exercise, I’ll work on internal and external shoulder rotation stretches as needed, especially during my warm-up sets. Using a band or the frame of a rack, I’ll go into an external rotation stretch to open up my pec minor, front delts, and subscapularis, holding for a good 30-60 seconds until I feel it release and trying to concentrate on squeezing my upper back instead of just cranking the stretch as hard as possible.

If I’m having a hard time getting my lats to flare open, I’ll do some internal rotation stretching for posterior delt, rhomboids, and the external rotators of the shoulder. This is one that I picked up from one of John Meadows’ seminars and it’s a great addition. I tend to fail internal rotation on structural balance testing pretty dramatically, and I like to use these particularly on either unilateral rows like the one-arm barbell row, dumbbell row, or Meadows row, or on vertical pulls with a wider grip like rack pull-ups or wide grip pulldowns. I use this for anything that requires a bit more internal rotation to get into position. Again, this is usually for around 30-60 seconds, keeping the stretch pretty gentle and not forcing it. It usually gets better as I go and I’ll drop it once I feel like I have the range needed for the movement.

I like to drop these in, particularly on heavier base days between warm-up sets. Ideally, by the time I get to my working sets, I don’t need to use them as much, but I’m doing it more and more with the weather getting colder and not warming up as quickly.

Reducing Bicep Involvement

I’ve always felt like I am pretty good at pulling with my back and not my biceps, but a slight adjustment to my vertical and horizontal pulls has improved my pulling mechanics even more. I have always had a tendency to go to full extension of my arm at the end range of all of my pulls, but have adjusted to leaving a slight bend, maybe five degrees or so, in my elbow at the end of the stretch. Those first few degrees of elbow flexion are completely bicep-driven, and the only purpose is to get the arm into position where you can then lead into the row or pulldown with your elbow instead of your hand. So it’s essentially a wasted movement that removes tension from the back and places it into the biceps. Keeping that slight bend forces me to extend through my back and not my arm, trying to extend the weight as far away from me as possible by either elevating or protracting the shoulder blades, depending on the movement.

A Twist on an Old Favorite — The Scrape-the-Rack Deadlift

I stumbled on this one more by accident than anything. My workout one day called for rack pulls, and it was a busy rush hour time (which I rarely have to train in anymore) and I couldn’t get a free barbell anywhere in the gym. So I ended up doing them on a Smith machine and noticed that the fixed path of the bar required me to keep more tension in my lats so I wouldn’t get pulled during the descent. I took note of the exceptional level of soreness that followed the next day, with little to no DOMS in my lower back and hamstrings, which isn’t always the case with traditional rack deadlifts.

A few workouts later, I wanted to repeat it but this time both of the Smith machines were taken. I had done various scrape-the-rack movements before—barbell rows, overhead presses, flat presses—and figured it could work with a rack pull.

I like these best when rack pulls are used near the end of a workout and the lats are already a bit exhausted. When they’re called for earlier (second or third) in a workout, I’ll do traditional rack pulls and go a bit heavier. I can pull 405 for three reps from mid-shin on a standard rack pull but haven’t gone over 295 for five with the scrape-the-rack version.

The Pump Day

If you’re familiar with John Meadows’ Mountain Dog programs, you’re probably familiar with the concept of the pump day – a second weekly session that’s stripped of a lot of the heavier movements and the crazy drop sets, forced reps, and challenge sets that John’s programs are known for. Instead, the focus is on driving tons of blood into the muscle while still facilitating recovery before the next heavier base day session comes around again.

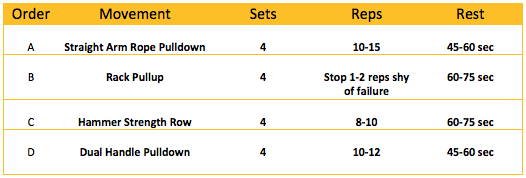

On the recommendation of Mountain Dog lead coach Cris Edmonds, I’ve been using this sequence to lead off those pump days:

Straight Arm Rope Pulldowns

I like using a rope more than a straight or cambered bar because the neutral grip seems to help me get at my lats better than anything else. Don’t try to spread the rope, just keep the hands together. This sort of waving pattern with the reps and weight works very well:

- Week 1 — 4 x 10

- Week 2 — 4 x 12, same weight

- Week 3 — 4 x 15, same weight

- Week 4 — 4 x 10, slight increase in weight (five to 10 pounds)

Once you hit a point where you can’t get all of the reps as prescribed, you can either back the weight down slightly for a week or two, or rotate in a new exercise for a couple of weeks. Or you could just stay with a rep range that you can hit without reaching failure.

Rack Pull-Ups

I’ve seen these for years and had never given them a fair shot until Cris had me work them in. I’ve had beginners use a feet-on-the-floor version for a long time but had never given the proper feet-elevated version a chance. These work as a follow-up to the straight arm pulldown very well; use the pulldowns to concentrate on the contraction, and the rack pull-ups to get a bigger stretch than you could with a traditional pull-up. Adding in a 20-30 second stretch at the bottom of the last rep on two to three sets is a great touch as well.

From there, add in one rowing movement for the lats and one upper back movement — something that gets the elbows out a bit wider and behind you, whether it’s another row, a prone shrug, or a behind-the-neck pulldown. If you can find a pulldown station that has two separate pulleys, you can use it to mimic a behind-the-neck pulldown without worrying about constantly hitting yourself in the head with the bar. FreeMotion and Life Fitness both make versions of this. Just lean slightly forward into it so the path of the handles mimics a behind-the-neck pulldown and not a front pulldown.

WATCH: Mountain Dog Back and Biceps with Mark Dugdale

Zach is the co-owner and head strength coach of All Strength Training, a personal training center specializing in busy professionals located in Chicago, IL. He is also a competitive physique athlete, earning his WBFF fitness model pro card in 2016, and is training for his pro debut in 2017. For more information visit www.allstrengthtraining.com.