As any sports performance coach knows, training athletes in-season is no easy task. There are many variables at play and an ever-changing schedule that the sport coaches, athletes, and strength coaches have to work around.

These variables make it challenging to plan ahead. Without adequate preparation, you run the risk of your team training sessions evolving into a pseudo-yoga class, stretching out the athletes and leading banded walks twice a week for the duration of the competitive season. If you haven't had to fill that role in your career yet, congratulate yourself and consider yourself lucky because you have most likely worked with an awesome staff who is great at communicating.

Do your best to make sure it never reaches that point because it is no fun (at least in my opinion), and we didn't get into the field to lead stretches, warm-ups, and cooldowns. We did it to train athletes and maximize their athletic qualities to watch it transfer to success in their given sport.

RECENT: Training the Aerobic System to Maximize Adaptations

I'm sure most of you reading this will relate to the following story. When I first started training athletes as a new coach, I designed an entire training program down to the number of reps and sets at a specific percentage for the upcoming in-season competition schedule. My program was based on what was discussed with the coaches before the season pertaining to our "planned" practice schedule and opponents throughout the year. After these conversations, I would design a training program for the athletes to develop specific qualities I believe they needed to be prepared for competition throughout the season.

In theory, this seemed like the right thing to do because I wanted to be as prepared as possible for the long road of in-season work that was ahead. After going through my first couple of years of in-season training, however, I realized that this was an overkill approach because we have very little control as sports performance coaches.

It was very frustrating that I always had to keep rewriting all the training programs that I was spending so much time putting together leading up to the in-season. I knew my approach was broken, and I had to develop a more efficient method of getting the job done.

Shifting from Block to Vertical Integration

The first step to fixing this problem was moving away from block periodization and shifting toward a vertical integration method. I love block periodization because it provides the strongest possible stimulus for whatever specific adaptation you are targeting. Also, it is a great fit for off-season training if you have a specific goal for certain periods of time based on the overall training plan.

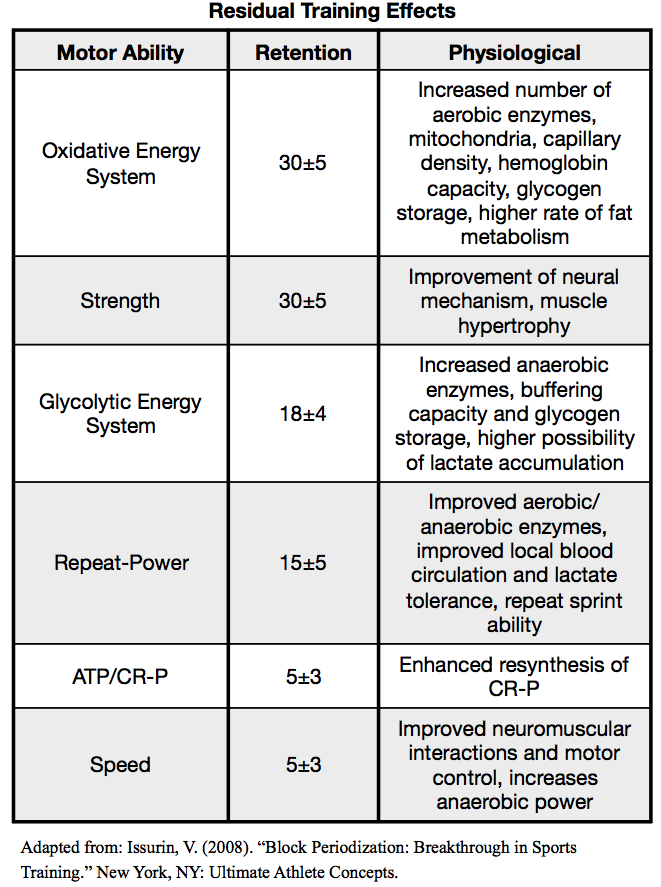

I did come to realize, however, that it is not very effective for in-season training because the amount of stress you are placing on one adaptation will have too many drawbacks on all the other adaptations you want your athletes to maintain. There are too many negative effects because even though the one specific adaptation you are focusing on is getting an extreme training effect, there are many other adaptations that are either maintaining or falling off. As we all know, athletes typically need to be somewhat capable in most if not every training adaptation to succeed in sport.

This is when I began to consider an approach to address almost all training qualities each week rather than focusing on just one quality per week. In doing so, I picked the exercises that gave the athletes the best "bang for their buck" each training session to cover all of our bases. I then shifted my in-season training to a vertically integrated approach. The goal of this approach was to work on every major training quality year-round, so my athletes were prepared for whatever their sport may challenge them with.

To design this approach, I looked at each week and phase of training as an empty bucket. I would decide how much of each quality I wanted to add to the bucket until it was full. In doing this, I always err on the side of caution because I'd always rather have my athletes leaving the weight room wanting a little more than asking if they could cut back on a few sets because they were feeling run down. I also found the biggest benefit of vertical integration was that it made me not have to worry as much about the training residuals of the different qualities. This is because we would never detrain any adaptation if we were always touching on everything week to week. The last thing you want is for your athletes to feel like they are missing something at the end of the season when competition is most important.

Microdosing

Microdosing your training ties directly into the vertical integration approach I referenced above. It's the practice of performing small amounts of specific training to physiologically benefit while minimizing the undesirable side effects. This is the key to designing a successful vertically integrated program for in-season training. Going back to the bucket analogy, you decide what percentage of your total training volume to dedicate to each training quality and fill your bucket up from there.

At different times of the in-season, you can choose to focus on certain qualities over others. Factors include the strength of schedule, number of competitions, plans for future phases, and what was performed in previous training phases.

To utilize the microdosing method, you train the other qualities with very low volumes to hopefully make small improvements on those adaptations or, at the very least, maintain them. Therefore, when you can train them with higher volumes during a period of time, you are not just bringing them back to where they were. This approach allows you to improve those qualities from a baseline that you have maintained due to microdosing. Suppose you stray too far away from training a certain adaptation. In that case, it is a recipe for never making any real improvement in that quality and always maintaining or regressing to the baseline you established in the off-season.

The challenging part about implementing this programming style during the in-season is that the training stimulus must be strong enough and apply enough stress for an adaptation to be made. The key is designing a program that will provide options on when you can implement certain training sessions based on the competition schedule and what the athletes need. To have this ability of "flexible" programming, I started writing a four-day per week training program, even though we'd often only be training two to three days a week, so I'd always have options based on what I thought was the best fit.

Creating Training Day Options: High and Low Days

As I mentioned earlier, it's very difficult to lay out an entire in-season training plan before the year starts based on the possible changes that are likely to happen. However, you can create a training week template for your perfect scenario that provides you with options. I have found that having four planned training days each week, even though you will most likely only train two to three days, comes in handy because then you can plug in any two of those four days based on the situation you are dealing with. To create a spectrum for the high and low days, I utilized ideas from Charlie Francis, Louie Simmons, Cal Dietz and manipulated them for the population I was working with.

I categorize the four possible training days for each week as high, medium-high, medium-low, and low (or whatever you want to call them) stress days. Some variables that may affect what days you choose are competition the previous and next week, practice schedule, team dynamic/morale, exams/holidays, etc.

The training days are ranked from high to low based on how much stress they apply to the athletes. To be more specific since all training induces stress, the high and medium-high days apply stress that may initially lead to less optimal sport performance due to the nature of the movements chosen. On the other hand, the medium-low and low days are designed to make the athlete feel primed and fresh for the upcoming competition. The major reason for the breakdown between the four days is to make sure you never lose any specific adaptation. Everything is always building or being maintained, as outlined in the training residual chart.

Training Design Template

Below I break down each training day even further to help anyone put together this four-day model that makes running in-season training much easier. As you'll see, I use the main lift selection as my guide for the rest of the session to organize things and create the high, medium-high, medium-low, and low days.

Training Split

Upper and Lower

For the training splits, I keep each day as either completely upper body or lower body. I do this for a few different reasons. The main reason is that upper body training will always be less stressful and fatiguing than lower body training because the loads are much lighter. After all, you don't have to factor in your body weight, and the musculature is smaller in mass, making it require much less recovery. This concept made it much easier to delineate high from low days. Also, in my opinion, athletes enjoy knowing what body parts/muscles they will be training leading up to a game. This doesn't mean you still can't perform a total body training day due to time constraints. All you have to do to set that up is mix and match pieces from different upper and lower body training sessions, which I have done in many instances.

Main Lift: Max Effort and Dynamic Effort

I decided to keep it simple and base it on Louie Simmons's Westside Method. For our main lift, we lift at very high intensities to get stronger and improve the force end of the force-velocity curve (FVC). We lift at lower intensities to produce more power and improve the velocity end of the FVC.

For the max effort lifts, I keep the reps between one to five, so we are recruiting high threshold motor units. I typically only use the full range of motion movements for this category, so we are developing strength in deep ranges of motion where individuals are often the weakest.

For the dynamic effort lifts, I keep the reps between one to three for six

-12 sets, so too much fatigue doesn't build up, and output/velocity stays high across all sets. I like to have my athletes perform these sets on a clock, usually every 60 or 90 seconds, to keep intent high and develop some alactic conditioning. As the competition season goes on, I tend to start using more partial range of motion movements to control ranges of motion and keep intensities high as fatigue gradually builds.

Speed, Plyometric, and Med Ball Training

During this piece of training, the goal is to develop general athleticism by performing a variety of jumps, sprints, and throws/slams. I have found it easiest to differentiate the days by having my lower body days only consist of speed and plyometric exercises and my upper body days consist of only med ball throw and slam exercises.

On max effort days for the speed training, I will perform my highest velocity and longest duration sprints, typically some sort of fly or extended accelerations.

For plyometrics, I will perform loaded jumps, jumps from deeper ranges of motion, or single-leg jumps to target a more intense strength adaptation.

For my med ball throws/slams on upper body max effort days, I will use heavier implements to slow down the speed of the movement to make them more force-oriented to build strength.

On dynamic effort lower body days for speed work, I perform shorter duration accelerations from a variety of start positions to make sure I am not overly fatiguing the athletes' central nervous system, plus keeping them primed for competition. For plyometrics on this day, I have my athletes perform unloaded or assisted jumps from shallow ranges of motion to keep movement velocity high. I often include more ankle dominant jumps than the knee dominant ones I would use on a max effort day. Then for the med ball throws/slams on dynamic effort upper body day, I keep the implement load light, so the velocity of the movement increases from the max effort day.

Accessory Lifts: Isometric and Eccentric

As for the accessory portion of the training, it is based on the repetition method made popular by Louie Simmons, but with a small twist because it utilizes eccentric and isometric-based movement, both popularized by Cal Dietz.

For max effort days, I use eccentric-based movement with higher reps. The target duration for these sets lasts between 20-30 seconds. I use eccentric for these because individuals are up to 50% stronger during the eccentric portion of a movement, so it will allow us to use heavier loads than if we were using straight rep sets. Also, it helps with tissue remodeling, making sure we are maintaining muscle length and range of motion. I prefer the sets to last longer because they are more stressful from a metabolic perspective than shorter sets. After all, it taps into the lactic system, so it matches well with the higher stress of a max effort day.

For the dynamic effort days, I use isometric-based movements with lower rep sets. The target duration for these sets is 10-12 seconds. I like to use isometrics on this day because we can touch on strength adaptation with lighter loads than you typically need by performing holds at the bottom range of motion where individuals are always weakest. Lastly, I keep the sets shorter to keep training strictly alactic to limit metabolite build-up and delayed onset muscle soreness.

Advanced Methods: Complex and French Contrast Training

With more advanced groups of athletes, I like to also utilize either complex training or french contrast training. Complex training, also known as post-activation potentiation, involves the integration of strength training and plyometrics in a training system designed to improve explosive power. An example of this is pairing a back squat with a box jump.

French contrast training is based on a combination of complex and contrast methods. The idea is to use four exercises to induce physiological responses of the athlete and train along the entire FVC. An example of this is performing the following series of exercises in one giant set: back squat, hurdle hop, weighted jump, and band accelerated jump.

On the max effort (higher stress days), I pair the main lift with a french contrast to present the athlete with the strongest stimulus possible in-season. I like to pair it with the max effort method because we are getting a large post-activation potentiation effect from the high-intensity lifts recruiting high threshold motor units. It also works better because there are fewer working sets on this day since the intensity of the lift is so high, and the volume of jumps within a french contrast is also high.

On dynamic effort days, I pair the main lift with a complex movement. I prefer it on this day because then we can get in a lot of high-quality sets of both movements since reps are kept so low for both, and the potentiation effect heightens and works both ways as the sets go on. Also, you can use plyometrics that have minimal negative side effects, like a box jump, paired with a lift that leaves the athlete feeling fresh.

Conditioning: Alactic and Lactic Energy Systems

Lastly, in regards to conditioning, I like to separate my days by the proportion of lactic and alactic work done. I build the conditioning directly into the weight room training sessions, so the athletes do not have to do extra volume on top of our weight training session, practices, and games during the in-season.

The conditioning during our high and medium-high days is both alactic and lactic. The alactic conditioning takes place during the French contrast method if you choose to use it. The goal is to improve repeat sprint ability by performing multiple low-rep high-output sets in a row, followed by an extended period of active recovery. Then during the eccentric accessory work that follows, it is lactic conditioning due to the higher volume working sets that have minimal rest between—very similar to common bodybuilding protocols.

The conditioning during our medium-low and low days is purely alactic. During the dynamic effort days, alactic capacity is developed regardless of whether the complex method is used because reps for both the lift and plyometric method stay in the one to three rep range. It is capacity training because the recovery is incomplete when the sets are performed on a clock like mentioned above. Then during the isometric accessory working sets that follow, alactic capacity is again targeted with the longer duration alactic sets by never going more than 12 seconds each set.

I chose to only use alactic energy system training on the medium-low and low days, hoping it would keep the athletes feeling as fresh as possible for competition with the low-volume, high-quality sets. Additionally, most sports are based on repeat sprint ability. Therefore, this system mimics the demands of a game—high effort sprint followed by short rest and repeat. The team that can successfully do that at a higher level for longer wins.

High Day: Lower Body

Top End Speed

- Speed

- Alactic Power

Deep, Weighted, Single-Leg Plyometrics

- Power

- Alactic Power

Max Effort Lower Body

- Max Strength

- French Contrast Method

- Alactic Power

Eccentric Based Accessories

- Tissue remodeling & Hypertrophy

- Lacitc Capacity

Medium-High Day: Upper Body

Heavy Med Ball Throws/Slams

- Power

- Alactic Power

Max Effort Upper Body

- Max Strength

- French Contrast Method

- Alactic Power

Eccentric Based Accessories

- Tissue Remodeling & Hypertrophy

- Lactic Capacity

Medium-Low Day: Lower Body

Accelerations

- Power

- Alactic Power

Small ROM/Light/Assisted Plyometrics

- Speed

- Alactic Power

Dynamic Effort Lower Body

- Power

- Alactic Capacity

Isometric Based Lower Body Accessories

- Strength

- Alactic Capacity

Low Day: Upper Body

Light Throws/Slams

- Speed

- Alactic Power

Dynamic Effort Upper Body

- Power

- Alactic Capacity

Isometric Based Upper Body Accessories

- Strength

- Alactic Capacity

Conclusion

I really hope this template assists you with writing in-season training in the future and provides you with useful guidelines. I purposely did not include any specifics (number of sets, reps, or percentages) because I feel everyone's situation with different groups of athletes is so different that it is not applicable. Designing training programs is always a work in progress and is never set in stone with all the changes we face every year. I hope this helps set up the general framework of your program for the year.

Regan Quaal is the Assistant Sports Performance Coach at the University of Minnesota with Cal Dietz.

2 Comments