“You're about to go to battle with that bar for the war of GAINZ.”

You are a warrior. The gym is your battleground. You will attack the loaded bar as a berserker charging against its enemies, using their open skulls to toast the victory of another PR. Until you have some serious altercation with another member—or worse, the gym owner—about using the wrong bar, putting the bar in the wrong place, rack pulling a bar, rack pulling one specific bar (and you will be confused about why those people are so mad at you), throwing the bar from an overhead position, or you simply can’t find some bars anymore.

Don’t worry, we've got you covered! Read on and you’ll understand why those folks weren’t too friendly with you and how to help the gym community take care of this important equipment. In the future, who knows — you might find yourself considering having your own home gym. The information here will help you make a good choice when purchasing bars.

Joe Versus the Bar

On February 9, our teammate and powerlifting champion Joe Sullivan was training at a generic gym, out of town. He loaded the bar as he squatted until he reached 675 pounds (or 306 kilograms).

“I should have inspected the barbell better and not put myself in a bad position. (…) The biggest takeaway from this thing is that I wasn't hurt. I'm very fortunate to have walked away relatively unscathed.”

Actually, according to Ivanko Barbell Company founder and owner Tom Lincir (2001), that wouldn’t be quite as easy as Joe assumed. The reason why the bar “melted” the way it did is probably related to mechanical phenomena like stress and fatigue, or to micro-structural issues, which cannot be detected without proper equipment. In fact, even cheap commercial bars can take quite a beating before they bend. Or they can bend exactly the day you load it with the extra kilo that broke the bar’s resistance – or the straw that broke the camel’s back.

This video shows cheap barbell resistance:

Let’s take a closer look at these properties, and how you can use this information to choose your bars and maintain them.

What Bars Are Made of and How

Any of the five types of competition bars (the two weightlifting Olympic bars—male and female—and the three powerlifting bars—the power bar, the deadlift bar and the squat bar) are made of a steel alloy and are comprised of a bar shaft and revolving sleeves. This list outlines some properties that are relevant in the quality and behavior of bars and also vary among them:

- Tensile strength

- Hardness

- Straightness

- Ductility

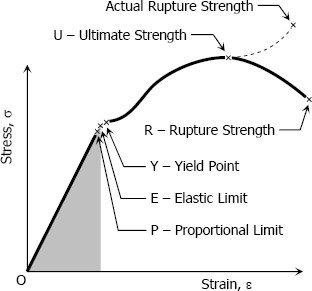

The first quality presented by a manufacturer about a bar is its tensile strength. The tensile strength is the force required to pull the bar apart and is measured in pounds per square inch (PSI). The picture below describes what happens as you load a bar. What you don’t want your bar to do is to become permanently deformed. It will bend under strain, but as long as the strain is below the elastic limit (in the shadow triangle), it will not lose its straightness:

Each type of steel (alloy) has a different curve. Also, the way the bar is made and hardened—when and how heat is applied—changes the curve, therefore the bar’s properties. Lincir (2001) described how, over the years, metallurgists and training experts came to realize that the previously accepted minimal PSI of 150,000 was not enough and that anything below 190,000 PSI developed permanent bends over time. To achieve that, the cost goes up; higher quality steel is more expensive and bars with PSI of 190,000 or more are more expensive to machine. That is the reason why ultra-hardened, super-strong bars manufactured by Eleiko, Ivanko, Uesaka, and others are much more expensive. Today, most “super” bars are well over 200,000 PSI.

Two other factors may determine less-than-optimal bar performance or even catastrophic results: microstructural problems or surface defects. According to Lincir (2001), after ultrasound (microstructure) and magnetic particle testing (surface defects), Ivanko rejects about 6% of their finished bars. It is possible that cheaper bar manufacturers may not either test so much or be willing to reject potentially profitable merchandise. But hydrogen embrittlement, inclusions, internal flaws, or hairline cracks have caused catastrophic damage in the past, including the death of lifters. Grooves cut into the bar are called “suicide grooves” for a reason (Lincir 2006).

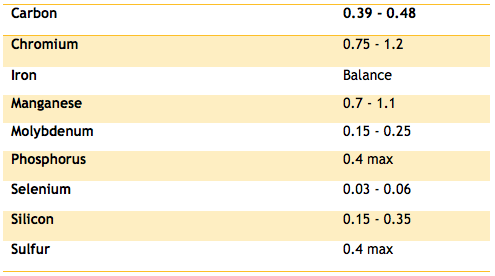

Bars are made of steel, which is an alloy of iron with other elements. The most important (and determinant in regard to mechanical properties) is carbon. Take, for example, the popular ETD 150. This is its chemical composition:

Since the basic element is iron, one of the first concerns with steel equipment is oxidation, or rusting. There are two options to avoid rusting: using stainless steel, which is more expensive, or using coating (the black oxide coating), which is less expensive than stainless steel but is more expensive than the non-coated non-stainless steel.

Anecdotally, proper execution of weightlifting exercises involves taking advantage of bar deformation to enhance the ability to raise the bar to sufficient height for a successful lift (Chiu 2010). Ideally, a weightlifting bar will have as much spin as possible (because there will be less horizontal displacement on the catch) and just the right degree of “whip” (vertical displacement). Ideally, a powerlifting bar will have less spin, for more stability of the barbell-lifter-system, and less whip (more stiffness), especially for the squat and the bench press.

The “spin” is provided by the internal structure of the sleeve, shown in the Eleiko “anatomy” video below:

This is a video made by Chris “Mad Scientist” Duffin—owner of Kabuki Strength and strength training designer and manufacturer for many years—explaining some concepts about barbell metallurgy and how it applies to bar longevity. He gives special attention to tensile strength and hardness as it concerns barbell resistance to deformation:

Olympic Bars: General Types

As was mentioned before, competition Olympic bars today can be divided in two broad categories: weightlifting Olympic bars and powerlifting bars. In the beginning, there was only the “Olympic bar,” created for weightlifting Olympic events. Let’s start with the weightlifting bars.

Weightlifting Bars

Men’s Weightlifting Olympic Bar:

- 2.2 meters (7.2 feet) long

- 20 kilograms (44 pounds)

- 50 millimeters (2.0 inches) in sleeve diameter

- 28 millimeters (1.1 inches) in shaft diameter

- 1.31 meters (4.3 feet) in shaft length

- 910 millimeters (36 inches) between grip marks

Women’s Weightlifting Olympic Bar:

This bar is similar to the men's bar with only a few differences.

- 2.01 meters (6.6 feet) long

- 15 kilograms (33 pounds)

- Smaller grip section diameter (25 millimeters, or 0.99 inches)

- No center knurl

Powerlifting Bars Compared to Weightlifting Bars

- 20 kilograms (44 pounds)

- 2.2 meters or (7 feet, 3 inches) long

- 28 to 29 millimeters in diamater

- 81 centimeters (32 inches) between rings

- 25 kilograms (55 pounds)

- 2.44 meters (8 feet) long

- 30 to 32 millimeters (1.25 inches) in diameter

- 30.5 centimeters (12 feet) center knurling

- 1.45 meters (57.5 inches) shaft length

- 43 centimeters (17 inches) loadable sleeve length

- 20 kilograms (44 pounds)

- 2.3 meters (7 feet, 5 inches) long

- 27 millimeters (1 inch) in diameter

- 39 centimeters (15.5 inches) loadable sleeve length

- 1.42 meters (56 inches) between sleeves

- No center knurl

Male weightlifting Olympic bar, deadlift bar, and squat bar from top to bottom

Male weightlifting Olympic bar, deadlift bar, and squat bar from top to bottom, a closer look at the knurling

Male weightlifting Olympic bar, deadlift bar, and squat bar, from left to right

This video shows the Texas Deadlift Bar by "PowerliftingToWin", with a comparison between a deadlift bar and a stiff (power) bar:

This video shows the Texas Squat Bar by "PowerliftingToWin", with an explanation about the importance of the bar stiffness and long central knurl:

The five competition Olympic bars:

From top to bottom: squat bar, deadlift bar, male weightlifting bar, power bar, female weightlifting Olympic bar

From left to right: female weightlifting Olympic bar, power bar, male weightlifting Olympic bar, deadlift bar and squat bar

Maintenance

By now, some of the measures to keep your bar straight, with the least possible accumulated stress and fatigue and no rust, should be evident. The super-uber highest quality bar manufacturers will actually say their bars have a “lifetime guarantee.” You know, of course, that someday, enough fatigue and stress will accumulate and eventually damage the bar. But you will probably die long before it happens to these bars. Even then, most super-uber high-quality bar owners won’t even allow you to look at their bars, let alone use them. If he is your friend, he might allow you to perform a few quick lifts (snatches, cleans, clean and jerks), but he won’t let you place a weightlifting bar on a rack.

Coker (1987) published a comprehensive guide to bar maintenance. The most significant damage to the bar is the “slight (irreversible) bend.” It is hard to visually detect this, but spinning the shaft of a bent bar will result in an uneven spin. Some of the damaging factors for permanently bending a bar are leaving weight on the bar. This is worse if the rack supports are too close together. Rack supports should be as wide as possible. Obviously, no weight should ever be left on the bar after using it. When the bar is on the floor, it should never be stepped on, leaned on, or sat on. Dropping the bar from any height can cause damage to it.

The company that created and commercialized a product for this purpose, Bar Shield, created a couple of instructive videos about bar maintenance in general for their YouTube channel:

And about the “deadly sins” of dropping an empty bar:

Takeaways:

- Instruct each new person to have access to the bars on their properties.

- Do not allow rack pulls with deadlift bars or weightlifting bars.

- Do not allow bars to be left with weights on the sleeves when hanging from the supports of a rack.

- Do not allow deliberate dumping of the bar or dropping it from overhead without keeping hand contact to ensure controlled descent.

- Absolutely no sitting or standing on the bar.

- Avoid humidity or water leakage over the bar.

- If you notice oxidation, apply good quality rust remover or neutralizer.

- Apply a thin coat of WD-40 to the sleeves once in a while.

Man and Barbell: A Love Relationship

More so than with other pieces of equipment in a gym, lifters tend to develop a personal (sometimes quite emotional) relationship with bars. To best illustrate this, I will recount a story that was told to me by former weightlifting world champion, president of the Russian Weightlifting Federation, and Master of Sports Maxim Agapitov.Once, at the warm-up area of an international weightlifting competition, a man stepped over a loaded bar. Shocked and in disbelief, the lifter using the bar went after the transgressor, grabbed him by the arm, and made him “uncross” his bar (step over the bar backward). Why would he do this? A few articles ago, I discussed the concept of private and intimate space in lifting. Crossing a loaded bar being used by a lifter is very often felt as the worst possible invasion of the intimate space in the lifting environment. Many lifters won’t like it even if you step on the platform. After all, while he is using it, it’s like “consecrated ground.” It is “devoted” to something special.

By now, you know that bars can be damaged. Most commercial gyms have more damaged bars than not, and lifters, even if they don’t know everything about the mechanical properties of bars, already know some of the things that shouldn’t be done to a bar. They become protective. These are some testimonials I collected:

“I changed the time I would go to the gym just so I could use the one good Olympic lifting barbell before the CrossFitters came in.” — Dean Saunders

“For our 25th anniversary (silver) I got my wife a top of the line Olympic Bar (15 kilograms) from Rogue; she loves it. The spin on the bar really helped with forearm issues she was experiencing.” — Carlos

“I really miss the cheap black bar at my old gym. It was my favorite. I would hunt it down every morning until I found where it had been moved to. I eventually started hiding it behind the dumbbell rack when I saw someone drop it from overhead. I loved that bar. The knurling was perfect; firm grip without tearing up my hands and spun easily when doing cleans. Now I train at home with a slightly bent bargain bar and I hate it with a passion that burns like a thousand fiery suns!” — Kenny Nicholls

“The Ohio Power Bar is that one friend you got that constantly tells you how much you suck and how you should be better. And it hurts you a lot, kicks your ego in the dick, but you know it’s good for you in the long run. The Ohio Deadlift Bar is that sexy chick who lets you score her phone number and makes you feel really good about yourself.” — Nill Josue Banegas-Saybe

“I've got a good one (story). A strength coach, who shall remain nameless, had an issue where all his facility's bars were getting bent. One of his assistant coaches, who competes in strongman, suggested ordering Texas Power Bars for the stronger athletes to use. The head strength coach came back excited a week later, saying he ordered the bars, and they cost less than half of what his assistant told him they would, so he bought 20. Turns out instead of Texas Power Bars, he bought the bars from a company called "Texas (other firm name)" or something like that and he had to buy new bars again six months later.” — Michael Colella

“My favorite bar back in the early days was this bar that was old and rusted. The knurled parts were just enough to grip it and the collars barely spun. The collars not spinning is why I liked it. I didn't know why at the time. It just felt right and was always available so I never had to fight for it, just had to dig it out of a corner” — William Lee

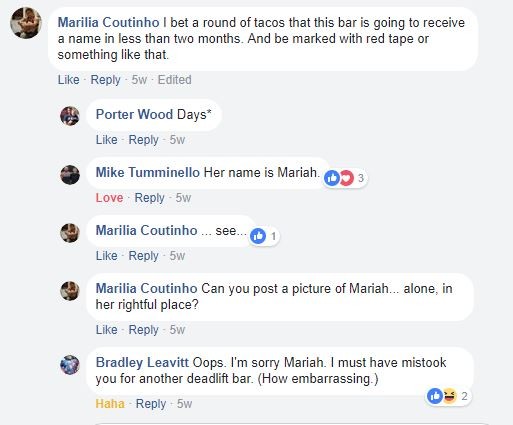

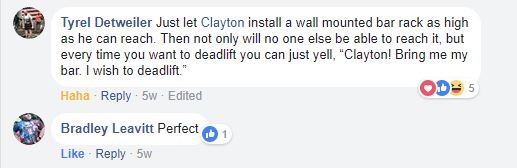

Mariah’s Story

Follow the exciting story of Mariah, the deadlift bar, through the next screenshots.

The takeaway from this story is that individuals get attached to bars for several reasons, the primary one being that good, quality bars are a component of good, quality training. There are, however, emotional aspects, as with everything in training; the “special” bar provides a sense of continuity, of predictability, and even intimacy. Don’t mess with anybody’s bar. Don’t disrespect bars in any gym, and learn how that community understands respect. Don’t step over people’s bars while they are training.

How to Choose a Bar

By now, it is probably clear that the main issue when choosing a bar is the price. Seriously, who wouldn’t want one of those perfect, uber-strong, uber-perfect, expensive jewels, developed through decades of industrial experience? Not everyone can buy them, let alone outfit a whole gym with them. Assuming you belong to the class of mortals that won’t buy 10 jewels, what is your best bet? Again, reputation and experience count, as Mr. Tom Lincir, Ivanko’s owner, emphasized in his articles. If you got to Mr. Colella’s hilarious story of the non-Texas bars, you probably understood what I mean; there are good companies out there selling decent bars, and we have plenty at the elitefts store. It’s probably not a good idea to go with a “generic” bar, way too cheap to be good.

These general guidelines should help you choose your bar. Let me be clear about what the conclusions of this articles’ research have taught me: You can buy the best bar ever, in the history of ever. If you don’t take care of your bar, you are not only throwing money out the window but you also may hurt yourself or the next lifter.

Finally, let me share information that Eleiko made available about its new generation bars:

Read More, Watch More

- Barbell Museum

References

- Chiu, Loren ZF. "Mechanical properties of weightlifting bars." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 24, no. 9 (2010): 2390-2399.

- Coker, Ed. "Weight room maintenance: The Olympic bar." Strength & Conditioning Journal 9, no. 4 (1987): 73-79.

- Lincir, Tom. "How To Break an Olympic Bar." (2006).

- Lincir, Tom. "Why Olympic bars cost what they cost." Natl Fitness Trade J 20 (2001): 26-27.

Acknowledgments

Joe Sullivan, Bradley Leavitt, Dean Saunders, James Griffin, Kenny Nicholls, Michael Colella, Nill Josue Banegas-Saybe, Paul Stevenson, Teresa Barnes, Vladimir Ver Magnusson (all from the “Starting Strongman” discussion group), Jackson Sloan, Clint Darden, Erik Blomberg (Eleiko CEO).

I believe that if people were given this information the first time they walked into a gym, then most of them would spend the rest of their lives using and storing barbells properly -as well as other gym equipment. A 5-10 minute tour of the gym's equipment, including its uses, limitations, and care, would go a long way in significantly extending the life of it.

P.S. Thank you for letting me be a part of it. I really enjoyed it.