This article is a comparative analysis about strength training gyms that resemble “homes.” The goal here is to explore the concepts related to “homeness” on the choice of the training environment. It sets the ground for subsequent essays on alternative training settings and facilities and the concepts involved in their evolution. This whole endeavor is about the relationships people have with their training environments when training is a meaningful activity.

What should you expect to “take home” from this series:

1. An understanding about your relationship with the gym space/environment. This is useful for:

- Decision-making — Will you stay at that gym or move to another one? Will you build a home gym?

- Mood Control — Understand why you become uncomfortable or comfortable in gym situations and learn how to manage that in order to protect the quality of your training

- When is the moment to build a home gym?

2. How to build a home gym, how much it costs and what you need.

- What to expect from your home gym in respect to your training, your relationship with other people, and the sport.

3. What are your options after you have a home gym?

Introduction: “You Can Play With Us”

Scene 1: The Bulgarian Olympic Weightlifter watches in horror as a random person at the World Championship warm-up area walks across (and steps over) his bar. He is so outraged that he goes after the stranger, whose language he does not speak, grabs him by the arm, and makes him “unwalk” his bar, as if breaking a spell. This was told to an audience during a lecture by Maxim Agapitov in 2014.

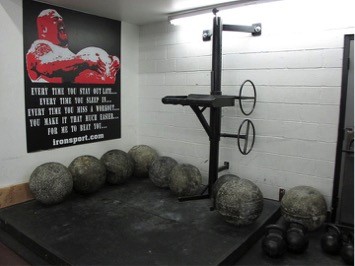

Scene 2: I met Steve Pulcinella at Iron Sport. Iron Sport is a traditional strength sports gym located in Glenolden, Pennsylvania, with not only equipment but also a history of achievements in Olympic weightlifting, powerlifting, Highland Games, strongman and bodybuilding. Steve is a coach, athlete and somewhat of a legendary figure, profusely used in memes all over the web. The year was 2011. We met at the front desk and Steve showed me around. There were different toys, like the adjustable Atlas Stone support. Lots of racks.

“Can I…?”, I asked. He said, “Sure.”

“Can I” is basically “can I play?” So I chose a rack and started to squat. After a while, some guy came and spotted me. He just said, “If you need help, I’m right there.”

Keep this phrase. We will come back to it later.

Iron Sport – Glenolden, PA.

Atlas Stones adjustable stand at Iron Sport

Scene 3: The year was 2012. My closest friend at the time was the founder of the first CrossFit box in Brazil, Joel Fridman. Three times a week we had our personal time together, usually from 1:30-4 PM. Alone, only the two of us, we’d “cross-coach” each other (and I did learn pretty good Olympic weightlifting, since he was a competitive lifter for decades) and talk about all things in the universe: was there an afterlife? What did all the lifts have in common?

There were societies without chairs. We even created a course during those unstructured (or, rather, super structured) moments.

Joel Fridman and I during our early afternoon cross-coaching personal time at “CrossFit Brasil”, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2011-2012.

One day a girl, a new member, came in by the end of our personal time. And then she did it: she walked over my bar. At that time, two other friends had joined us — they were allowed to come in the second part of our time. We froze. The three of them looked at me in apprehension: was I going to attack the girl? I did not. I just unloaded the bar and put away everything. Something was broken.

Where was the bar? Exactly in front of the bathroom. That was where “my” bar was, always. Why did we expect anyone to go around it to go to the bathroom? Because that was how we had organized the space.

My friend’s spot was facing a part of the gym where there were a few odd objects on the floor and a white wall. When a newcomer was (again) trying to get to the bathroom, someone would stop him: “Wait until he finishes the snatch.” That was the “infinite” wall. You can’t just cross in front of someone preparing to perform an Olympic weightlift. Just can’t.

Scene 4: Observe the picture that will head all the chapters of this series. This is our elitefts member Clint Darden and his son. This is his description about it: “I live on the island/country of Cyprus. That is me and my oldest son, Steven. I believe that he would have been three years old and was home sick from school so I took him to the gym with me that morning. It was the first time he had ever seen me really push myself. I had just done eight reps with 680 pounds on the box squat, blood running down my forehead (from smashing it on the barbell before my squat), and unable to move my left arm from impingement pain. He said he wanted to come and give me a hug. And he did, while the video camera was rolling. The year would have been about 2011.” (Clint Darden, personal communication)

RELATED: Why Do You Lift — Meaning, Identity, Hope and Passion

At CrossFit Brasil, one day two little boys from a poor neighborhood came into the box. Sao Paulo is a gated city: areas are strictly separated by economic activity, class and ethnicity. It’s an extremely violent place. The boys were “outsiders” at that world – a world that was richer, whiter, different. There was a moment of embarrassment and confusion before someone told them they were not supposed to be there because it was a training center. They didn’t know what that was. They both looked at me and one said to the other: “Is this a man or a woman?” One offered, “I think it’s a man." The other disagreed. Before they were told to leave, I asked both why they had the opinion they did. The one who thought I was a man said, “Because of the muscles. Only men have muscles." The other, who thought I was a woman, said, “Because of the hair. Women have long hair.”

The door of the gym, in Brazil, marked the immediate “defensible space” or territory. The street is, by definition, public space: the most public of spaces (Newman 1972, Shjarback 2014, Reynald & Elffers 2009).

All this time, we are talking about how we relate to our environment and how this shapes our relationship with other people, and vice-versa. We are also talking about non-verbal communication and how this multi-layered form of interaction shapes relationships with spaces and people (Hall 1966, Holmes and Spence 2004).

When we perform meaningful activities, those that create our identity, they define and are defined by the environment they take place in.

The Spheres of Space and the Home

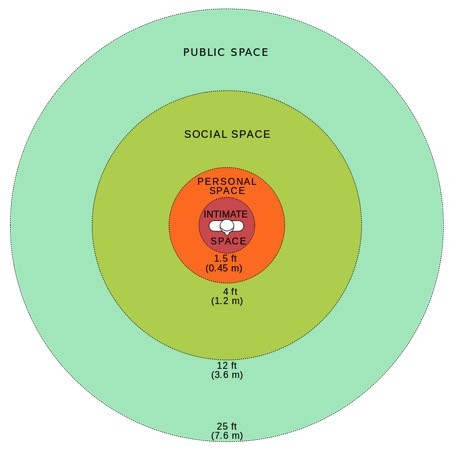

What horrified the Bulgarian Olympic weightlifter was the invasion of the innermost of the space circles: the intimate dimension, or “intimate space.” To outsiders, it doesn’t make sense. However, this is the dimension occupied by nursing babies with their mothers, lovers having intimate sex, and friends and family hugging (Clint’s picture). The relationship between lifter and bar is that intimate.

Las Vegas 2012, WPC World Championship: Me, kissing the bar after missing a record attempt and winning the championship.

Sao Paulo, Crossfit Brasil, 2012: Me, resting over the bar after a set of snatches.

The space that my friend and I shared in our “personal cross-coaching” time was the inner part of the personal space. It was so small that it contained only the two of us. Later we incorporated two or three other people, but we kept at least one hour free from them, just us. So, even at an apparently “flat” gym environment, time and space may be segmented in a very precise and sophisticated manner.

Along the past decade, CrossFit boxes evolved from tight little communities to more professional, commercial facilities. In those early days, most boxes were still personal space. They evolved to social space and, today, many are no different than chain gyms, clearly in the realm of the public space.

Figure 1. Diagram representation of personal space limits, according to Hall’s model. Inspired by Reaction-bubble.png by Libb Thims

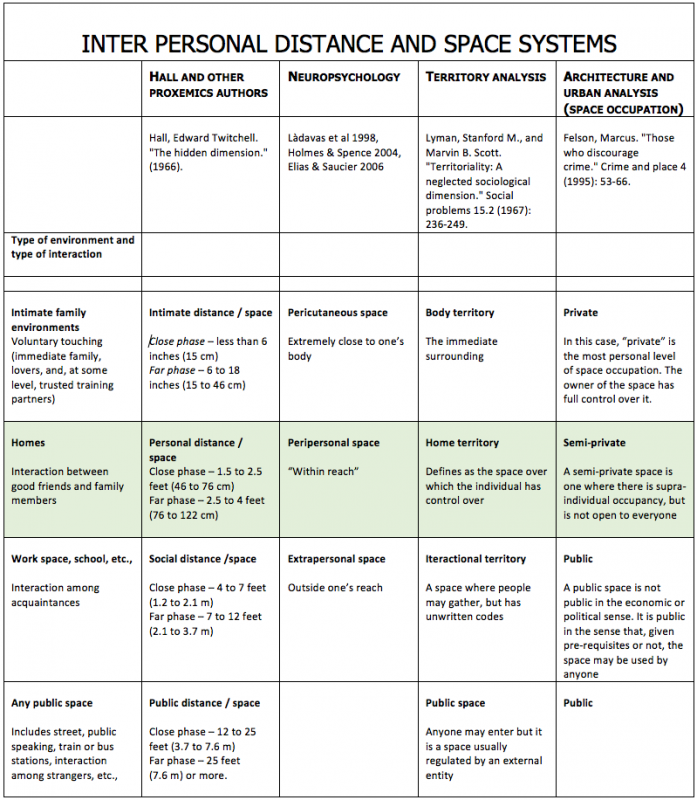

Below is a table that summarizes classification systems concerning inter-personal distance and space systems. To move on into our discussion about home gyms (gyms constructed at garages, basements and other quarters in private living spaces), we need to define “home.” To do that, the richest study objects are the gyms that, in spite of not being home gyms, are “home-like” environments.

They allow us to:

- Explore the differences between traditional commercial facilities and these “home-like” environments, bringing into evidence what is “home” in terms of training.

- Explore social relationships established in “home-like” environments.

The first thing that all scenes above tell us about is that what people were doing was special in a deep way. That is what we call “meaningful” activity. Meaningful activities are highly personal, as opposed to impersonal. Buying groceries, cashing money or drinking coffee at an airport lounge are impersonal activities. While we try to choose places that won’t make us feel uncomfortable, the relationship we have with these acts is not personalized and we basically connect with strangers. For most people, training is more impersonal than personal (because, as with most things, personal and impersonal are not clear-cut and occur along a spectrum).

The reason most people to whom training is meaningful feel uncomfortable in commercial chain gyms is not because they are rude or filthy. Actually, quite the opposite: they strive to provide the best possible amenities to satisfy the largest number of consumers for that economic niche. They will be clean, the staff will be smiling and solicitous, the music will be “general,” there will be a snack bar, apparel to buy for emergencies or marketing, spas and the space will be organized in such a manner as to guarantee a safety perimeter around each customer. But it is the externally structured time, the safety perimeter, and the impersonal nature of the relationship with what is done there that conflict with the needs of people to whom training is meaningful. It is really not about lack of equipment. Many of these gyms have excellent racks, good Olympic bars and plates. It is about personalizing the relationship with the activity, with the people, with the equipment, with the surroundings, and with the body itself.

Everyone needs structure and items around which life can happen, with its surprises, its rituals and its automatic and mandatory scripts. You have probably heard expressions such as “you (or someone) need to be more centered”, or “he needs a reference.” We learn about these things in our first occupied space: our family home. For Smith (1994), a home is defined by the qualities of centrality, continuity, privacy, self-expression, social relationships, and warmth. All of these qualities define a space that is occupied and defended from disruption.

This is a territory: space, from the Latin terra, and defensible space, from the Latin terrere. The home is where one feels or needs to feel safe in every respect (what we call “ontological safety”), which requires trust and personalization of the space (Dupuis & Thorns 1998). That goes far beyond the idea of having an alarm or armed security. One needs to feel safe about being seen and recognized as an individual. It is the safety of sharing values and building an identity related to the strength training and sports world (Dupuis & Thorns 1998, Reynald & Elffers 2009). Therefore, it requires continuity, stability and permanence (Tognoli 1987). It is a community (Douglas 1991).

Burger night at Iron Sport – March 15, 2015: “If your Friday night dates are all about the weights. And if your gym is full of Bros, and bitchy ass hoes. Then get your ass to a gym where right is right, and be a part of Iron Sport BURGER NIGHT!” (Steve Pulcinella, Iron Sport)

Privacy: “16-year-old Anthony getting his head right to smash a 425 with 200 pounds in chains for an easy double.” (Steve Pulcinella, Iron Sport, February 2016)

Warmth: “Powerlifters, putting their bags in their own way since 1965” (Steve Pulcinella, Iron Sport, October 12, 2013)

These models help us understand the many things we love about our “home-like-gyms," but also the things we don’t love so much. All communities struggle with negotiation issues. But that is what homes and families are.

Some of the “symptoms” that you are at a home-like gym:

- Shelves or closets where members’ personal items are kept

- Personal items, like shakers, slingshots, boxes, with a name on it (written with sharpie or a tag)

- A place where people prepare and eat food

- Gender-neutral bathrooms

- Bickering about music

- Bickering about spots (“that’s my spot”, “what’s your towel doing at my stool”, etc)

- Strict observance of non-written rules (and some bickering about them). For examples "Who wrote the number of sets with chalk on the monolift?”, “The monolift is not your blackboard, clean it up”, “Who left the deadlift bar on the squat rack?”, “Who did this mess at the bathroom?”, “Who didn’t put away this shit?”

- Structured time: team clusters by time and day (“the lunch hour people”, “the late hour people”, “Sunday shirted bench”, etc)

- Invisible codification of the space: “Paul’s corner”, “chatting bench”, “my rack.”

- Health is dealt with by the group: formally or informally, there are members who take the responsibility of the group’s health. It can be more or less sub-divided (doctors, PTs/kinesiologists, nutritionists/dietitians).

- The existence and recognition of authority figures (“elders of the tribe”). These can be either the actually older athletes, the founders/owners, the more experienced individuals (whether in coaching or in the health professions), or someone that becomes the general “caretaker” by consensus. Unlike commercial facilities, authority figures will approach anyone, educate them, prevent accidents — and this will be accepted and acknowledged.

- “If you need help, I’m right here." Older members will offer help to newer ones and there is a trend towards watching over everyone else’s safety

“How come every man, woman, and child somehow managed to go on the Internet and all learn that bullshit, rubber band hip mobility crap but none of you have figured out how to put the fucking bands away” (Steve Pulcinella, Iron Sport, July 2, 2016)

“Which one of my manly members was trying to protect his precious hiney and left me this mess at the gym this morning?” (Steve Pulcinella, Iron Sport, February 13, 2015)

References

- Douglas, Mary. "The idea of a home: a kind of space." Social research(1991): 287-307.

- Dupuis, Ann, and David C. Thorns. "Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security." The Sociological Review 46.1 (1998): 24-47.

- Hall, Edward Twitchell. "The hidden dimension ." (1966).

- Holmes, Nicholas P., and Charles Spence. "The body schema and multisensory representation (s) of peripersonal space." Cognitive processing5.2 (2004): 94-105.

- Newman, Oscar. Defensible space. New York: Macmillan, 1972.

- Reynald, Danielle M., and Henk Elffers. "The Future of Newman's Defensible Space Theory Linking Defensible Space and the Routine Activities of Place." European Journal of Criminology 6.1 (2009): 25-46.

- Shjarback, John A. "Defensible Space Theory." The Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology (2014).

- Smith, Sandy G. "The essential qualities of a home." Journal of Environmental Psychology 14.1 (1994): 31-46.

- Tognoli, J. (1987). Residential environmentals. In D. Stokols & I. Altman, Eds., Handbook of Environmental Psychology. New York: Wiley, pp. 655-690.

2 Comments