In meeting potential clients or speaking at conferences, I begin conversations by asking the one question that no trainer or coach knows should be asked of athletes, let alone understand how to interpret anyone’s answer to. Because in the future, those connected to exercise science in any way are going to require expertise in a subject that most today would see no connection to sports at all.

The question?

What video games do you play?

And if you think it doesn’t apply to sports, I can assure you that ignoring the topic truly defines what is old-school thinking and new-school realities as the science of athletic training continues to improve. Video games are an integral part of sports today by not only creating a whole new category of competition but also impacting the sports that don’t require computer screens to participate.

Given that 97 percent of high school students play video games today, the question for anyone in real (as opposed to virtual) athletics now is how playing them impacts their physical performance skills. Because with all conventional measurements being equal, the team with the best video game players will have a competitive advantage. Understanding that reality is the future of sports whether anyone wants to admit that fact or not.

RELATED: What Video Games Can Teach Youth Sports

I write for gamers, my fellow enthusiasts who enjoy the intellectual challenge that video games offer, which few realize that no textbook can duplicate. I also write for those who deem video games a complete waste of time. Regardless of their viewpoint, they’re here to stay. If anyone wants to truly be a part of elite sports from this day forward, then discussing video games from both their academic and their athletic implications will be a required component of physical sports performance. This is necessary if you want to be among the best coaches, trainers, or athletes.

anolkil © 123rf.com

For the science of video games and their biological impact upon their players, the new question in athletics is to know not only what games anyone plays but also if such games have positive, neutral, or negative effects on their sport-playing skills. And if you don’t know the answer, then welcome to the age of brain training. Because it’s the future of elite athleticism regardless of the task undertaken.

Bottom line up top: Science says that the world’s best athletes aren’t stronger in the gym; they’re stronger in their heads than their lesser-able opponents are. And if you refuse to recognize that training the brain is the new frontier of sport science, you will be left behind. Even more important is the science story that every athletic trainer of the future is going to have to know if he or she wants to remain relevant in this profession.

If you recall the uproar in the sports world over a video game called Fortnite last year, from my perspective, I would describe the furor as a complete joke. If the prince of England can declare the game to be an “addiction” for the children of his country, then my only question would be to ask him how boring it is there to live under his rule….

One cannot become addicted to video games despite what our culture says. And although those who despise my passion control its social discussion, I take a very different viewpoint from any politician. In an analogy to public outcry, I find it odd that people who can’t perform surgery aren’t allowed to run operating rooms. Yet our public perception of video games is determined by people who aren’t even smart enough to play them…

I’ll get to the story of video game violence at another time. So, for the moment, all I can tell you is that although the ignorant demonize video games as a scapegoat for their political and social ineptness, how they impact sports is the discussion that few in training want to participate in. The reality is, there’s a gold mine of athletic improvement at the hands of athletes, coaches, and trainers in learning to integrate the science of gamification with their own competitive preparation.

In the future, the truly skilled will not only understand that reality but also will invest time into playing video games that enhance specific mental components of anyone’s sport-playing skills, rather than seeking mere entertainment alone. Although the science of gamification is in its infancy, those who seek the cutting edge of sport research need to be able to discuss brain training just as they would the development of any other muscle in their bodies.

The coolest part of this for me is the story that different games have different cognitive impacts. And sometimes the playing effects aren’t even what anyone sees as possible upon first glance of the game itself. For those who don’t play video games, how playing a game with a TV can actually change and improve what I call the “functional biology” of playing physical sports is my own personal research interest.

A favorite example is the genre known as First Person Shooters. They are described in the media as the catalyst for our national violence epidemic because they involve operating weapons to compete. Science says that the players of them are documented as possessing better night vision skills compared with those who don’t play them. Magnetic resonance imaging studies back up the fact that video game playing not only physically changes how their players think but also measurably alter specific regions of the brain in terms of size when they are played.

The question of the future for athletes is very definite. Anyone can tell you how much weight he or she can lift. All of them can tell you how fast they can run. But how many of the athletes you know are able to tell you how fast they can think? If you, or they, don’t know the answer to that question, then welcome to my world of elite-level athletics.

The science of video game playing is simple, and even the ancient Greeks had a term for it: Tachypsychia. Translated, it means “speed of the brain.” My story is that it’s a term used by the Marines, which I’m refining. And a term unknown to the Army, which I’m introducing it to. Unfortunately, the athletic world refuses to acknowledge its existence.

And even though the athletic training industry wants nothing to do with video games, I truly do hope that you take from what I write is an opportunity to be a better athlete, coach, or trainer by legitimate means rather than illegal ones. The science is there to document why playing video games will become a necessary component of sport training. How to use them properly is not only the biology I work with but the foundation to improving anyone’s athletic skill. Academics refer to it as one’s brain plasticity. It’s the ability to adapt to cognitive challenges and, more importantly, learn from them.

To be a better athlete, one cannot merely rely on physical strength alone anymore. Training the brain to improve athletic performance is not just necessary for the modern athlete. Choosing to ignore the cognitive impact and perceptual improvements gained through video game playing is to knowingly fall behind in training science with your profession’s international counterparts.

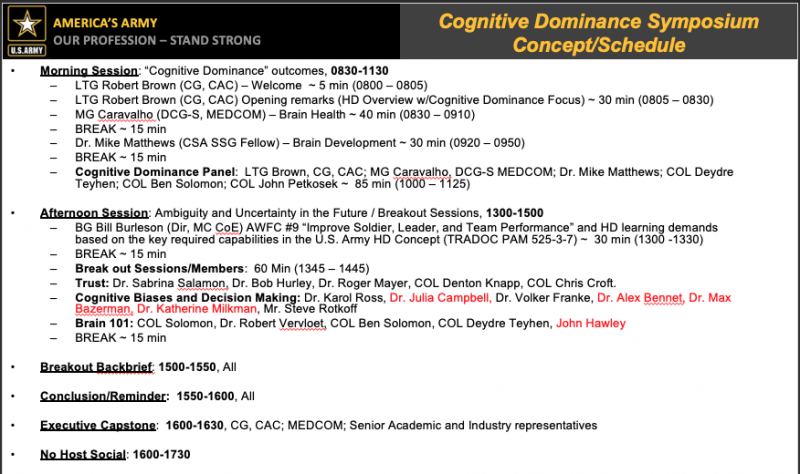

In fact, the only group in this country taking the video game discussion seriously is our military. With that, I’m honored to have had the opportunity to be invited by the Army to serve as a training and technology advisor to General HR McMaster with regard to my pursuits of video game applications and elite athletic performance. Although it will take time before my research finds way into a formal training doctrine for our combat forces, this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t have to wait until then to read what I’m writing for them.

With the foundation for improving physical skills being possible only when thinking speeds are increased, my military premise is to explain how video games improve combat skills in the easiest manner possible. In fact, the biology behind video games is very straightforward; the quicker any individual can think, the more information can be absorbed, processed, and reacted to—with the highest levels of precision and control.

For myself personally, not only have I been playing video games since the very first one (and no, it wasn’t PONG), studying them formally since 1976, but also I have been training athletes with them beginning in 1980. One of my early video game projects in 1985 was to be approved for teaching the first class in video game playing with police officers to address their personal violence issues.

And, of course, because you couldn’t get a degree in video games in my day, the academic side of studying video games, having absolutely no interest in my research, refused to acknowledge what is now referred to as cognitive function, neuroscience, or “brain training.”

As you could imagine, my parents hated video games throughout my childhood and even into my adult years, for that matter. Throughout, they refused having anything to do with my passion for playing them. What they couldn’t do, however, and despite their efforts, was keep me from enjoying my educational pastime. What they also didn’t realize is how I applied my video game playing to the sport I played throughout my schooling years, which was tennis.

Of course, coaches my parents paid for took credit for my abilities; however, none knew the role that video games played in refining how quick my playing reactions were. Fast-forward to today, and with the US Marines recognizing video game players as being 20 percent quicker thinkers than their non-gaming counterparts are, my studying video games now comes full circle.

The joke, of course, is that not only does our military seek guidance in applying video games to its training needs, the question that both Army and Marines are asking is if a 20 percent cognitive improvement through gaming is true, then what five video games do they want all recruits proficient in BEFORE they get to basic training?

Although my relationship with our military leaders continues to include the impact of video games to improve combat skills, what I seek to share with my readers is the science behind my list, and why both athletes and soldiers should become proficient in playing them. The list of video games with real sport applications is far more extensive than just five, but with that beginning and explanation, I’ll branch from there….

For coaches, trainers, or athletes, knowing the difference between video games is to understand why playing the most popular franchises of football, baseball, basketball, or soccer will never improve your personal game playing skills in those individual sports. In contrast, although the vast majority of video games for sports have nothing to do with the real game, any coach or trainer should also be able to explain why playing the top golfing video game on the market is documented in clinical studies as improving your golf scores.

If you won’t ask the video game question, then reaching the elite level of any sport is going to be extremely difficult. Whether anyone likes the fact or not, the best of our nation’s warfighters and athletes will have to be good gamers. How you deal with that truth will determine anyone’s athletic career from this day forward. What I seek to share is the story about why video game playing is so important for improving physical performance.

That reality is, I am writing to discuss video game playing from the perspective of knowing not only how much fun video game playing is but also how much can be learned by playing them. Openly, video games have been enjoyed by millions of people over the decades, and their impact has yet to be discussed without the blatant media and political bias against them. Unfortunately for old-world athletics, the new dawn of the video-game-trained athlete is here.

Or, as I quote the great philosopher Alice Cooper, “Welcome to my nightmare, I think you’re going to like it….”

More Reading

Header image credit: Sergey Nivens © 123rf.com

The Sport Jester is an independent researcher in elite athletic performance. Known for his extremely controversial training philosophies, his private students include the leadership of both medical and training commands of our combat forces. Today he is currently rewriting training manuals for both the Army and US Marines to assimilate his research into their formal doctrine.

I'd love to talk with you more about this.

I dont know whether anyone reading this is interested in another fantastic method of reaching their peak fitness goals but i thought i would post a link for anyone to look at. I think you will agree that its a winner. Thanks again and here is the link : http://muscles.media/rds5