Often as a teacher, parent or coach we set out to fix the world, child by child. We concern ourselves with where our children currently are —in terms of IQ, physical development, and emotional capacity—and where they should or could be. Once we discover the impairment, shortcoming, or delay (you name it), we then create an expectation for our child to follow. We are positive that this minor behavior and/ or change in performance will immediately solve the “problem” and that soon the child will fit our imagined ideal.

It’s time to throw out your expectations.

Imagine this: a much larger and grotesque version of yourself towers over your body. With your head cocked back, the face of a giant screams a forceful message, projecting saliva and hot air to mask your shadowed frame.

- Photo courtesy of Aaron Gilson

At this point, how willing are you to fulfill the given expectations? Did you even hear the request? Aren’t you more concerned with wiping off the layer of saliva dripping from your chin? Although the analogy above may be wildly exaggerated, did you ever stop to think if this is how you’re being perceived by a child? Especially for a child that lies somewhere on the autistic spectrum, the “I want you to [insert self-serving expectation here]”, may be seen as shouting insults with an image of horror. Intruded upon, the child’s main concern is to protect him or herself, and in the example above, find the nearest shirtsleeve. In this mental state, the likelihood of the child considering the expectation is like convincing a child to get a job and help out with the electric bill. Absurd, right? Despite the odds, the chance of you repeating and intensifying the same message is at an extraordinary high.

What if instead we used an alternative approach where we communicated respect and value rather than animosity, fear, and learned helplessness? Instead of dwarfing the child we kneeled down on one knee, eye to eye. Instead of screaming we used a calm voice and used a familiar language. After we used our words, we listened. Based on the conversation (using verbal and nonverbal feedback) we then adjusted our expectations to meet the needs of the child.

For the remainder of this article, the focus will be on how to meet the needs of the child instead of trying to fix him or her with unrealistic expectations. We’ll look at three case studies involving two boys and one girl, all on the autism spectrum. In each case, notice how expectations were created and adjusted, as communication became the primary mover.

Meet Brian.

Brian traveled to school and extracurricular events with a few of his favorite stuffed animals. His parents decided that for training (a new endeavor for the child) they’d remove the stuffed animals from his travel routine. Why their expectations had suddenly changed is beyond me. As you can imagine, Brian scrambled into the facility screaming and distraught for his training session. Despite a schedule and calm environment awaiting him, he wanted nothing with the planned activities or me. After a few minutes of observing Brian crying and thrashing his body onto the ground, I asked the parents if anything had abruptly changed since I had seen him last. “Oh yes, we decided that it was time for him to stop relying on Zippy and Zena.” Assuming they were referring to teacher aids or classmates, they were actually referring to the stuffed animals he closely associated with and took everywhere. Although severing reliance on two stuffed animals sounds like a practical growing up type of behavior the child could benefit from, now was not the time for him to experience this lesson. Placed in a new environment with a new face (we had only met once before) without Zippy and Zena, Brian was non responsive, uninterested and scared.

Rather than moving forward with the session, permanently giving Brian the option to associate the gym with harsh demands, we ended there and rescheduled for the following day, permitting Zippy and Zena to tag along. Thankfully the parents followed my recommendations with flexibility and availability, and on the following day Brian, carrying Zippy and Zena, walked into the facility. Brian was calm, receptive, and smiling. Over the next six weeks of training, Zippy and Zena’s presence eased Brian into a new environment with new demands. I welcomed them as I did Brian. What Brian did, they did, and if the activity didn’t include them, they watched. Having them around allowed my prompts and cues to be repeated and reinforced because after Brian completed the drill or exercise, Brian became the teacher/expert for Zippy and Zena. Obviously, if he hadn’t paid attention and listened closely, Zippy and Zena would be lost and unable to adequately follow directions. Around week three is when the inclusion of Zippy and Zena began to slightly lessen. Now they were joining us in specific activities and watching more. Around week five, they were sitting with mom in the waiting area and during free time they could be visited. At week six, they were in the car, patiently waiting to hear all about Brian’s training session. Brian’s dependency had naturally, with a slight reverse progression, lessened throughout the six-week period—ultimately what the parents were trying to accomplish, but in an alternative way.

Meet Ahleiah.

Ahleiah’s parents were concerned with her weight (fat gain predominately visible around her stomach) and lack of enjoyment with their home workout routine. The workout routine was administered after they noticed Ahleiah’s pants and shirts fitting snug around her midsection. According to her parents, “she always had visible abs but for the past year her abs are covered in fat.”

Digging into the matter more, past the physical qualities of her physique, I found that within the past year Ahleiah had gone through many dramatic changes: she began menstruating, she changed prescription medications at least four times within the past six months, and her diet switched to Vegan two months prior. Circling back to the home workout routine, this was administered by the couple to combat the belly bulge. The routine consisted of ab exercises and cardio.

The first place to begin was readjusting the parent’s expectations of how their daughter was going to lose the weight. I advised them to get Ahleiah’s hormones checked and see what internally was going on based on all the dramatic changes. Getting her hormones checked, for example, could at least serve as a starting place. The next area I wanted to place emphasis on was why they were administering the workout routine at home and how. We all know why they were administering the workout routine—to lose weight—but this was not going to convince a 10-year old girl to get moving. At what age does anyone want to do lying ab crunches on the floor and run in place? And why would anyone want to send a false signal to a young girl that direct ab work and running in place will shed unwanted body fat?

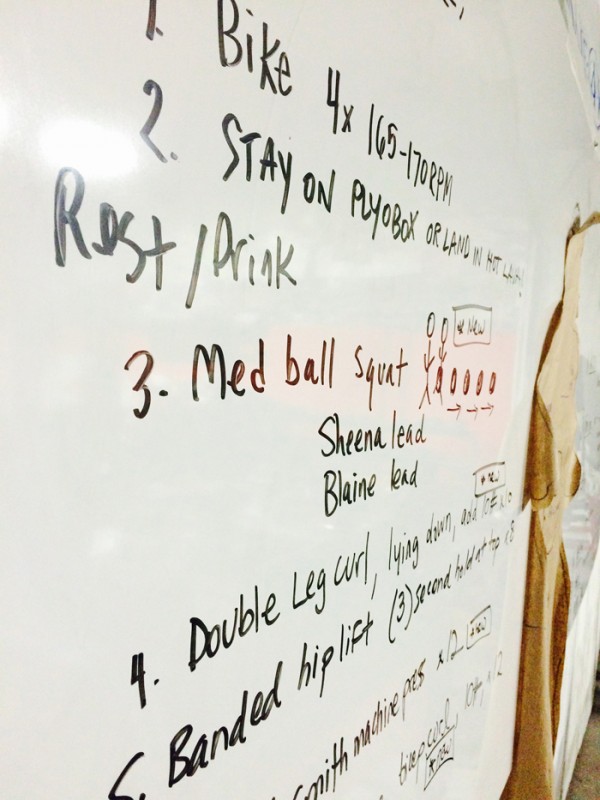

Getting the doctors on board, my next suggestion was for the parents to reanalyze the home activity they set in place. Rather than expressing to Ahleiah, “You’re gaining weight, so do these boring exercises to have abs again,” I instead wanted them to convey, “We want to have fun AND get stronger as a family!” Based on my weekly sessions with Ahleiah, I gave the family homework to complete as a family instead of the parents administering ab work and cardio for Ahleiah to complete. These home sessions were structured with a schedule and lasted, at the most, 20 minutes. The schedule, a mini version of our session in the gym, contained a warm-up, 1-2 main strength movements (areas that needed more attention based on performance in the gym, yet familiar to Ahleiah), a choice, and a game. Therefore, the setup reflected what we were trying to accomplish in the gym, yet was exchangeable with a new setting, mom, and dad. In Ahleiah’s case, as an extra motivational incentive, every time she completed a homework assignment she received points that would go towards earning a new notebook. She loved notebooks. Within a year, Ahleiah earned at least 30 notebooks!

Changing the parent’s perspectives and expectations allowed room for Ahleiah to associate exercise and play with fun, family time, and the chance to work hard for the things that held value to her. In that time frame, the parents were also working closer with the doctors to get her hormones on track, slowly changing her physique to reflect their now active and healthy lifestyle.

You know Blaine, but to continue with the flow, Meet Blaine.

Unaddressed in previous columns, Blaine absolutely loves his iPad, computer, and Nintendo DS. If he could bring his computer to each session without the hassle of packaging and chance of damaging parts, he would. Since that’s out of the question, he opts for his iPad and/or DS. Knowing his consumption of these games and Dave’s goals of providing Blaine movement, fun and strength, naturally my expectation was to void all use of video games in our weekly, one to two hour sessions.

Before long, I realized how my expectation was ridiculous and could instead decelerate our efforts. Surprisingly, in the direct opposite direction I intended to go, I’ve found the use of video games and YouTube (another love of his) to be useful within our weekly encounters. It first dawned on me how I could use these electronics positively to reach our goals, one day after Blaine completed a session that he described as “torturous, the sweating blood kind.” Within minutes he elaborated, “now that you tortured me with exercises, I’m going to torture you with Pokémon.”

I didn’t know how to take this at first but saw how it became a worthwhile request, as he relaxed and provided me with play-by-play instruction. He was the now the expert and I became the learner. Based on this encounter, I inserted free time into our schedule. This was the perfect opportunity to communicate with Blaine, “My turn first” and “then your turn.” Therefore, all the “pain” I put him through would be worth it in the end since he’d earn time to do exactly what he wanted to do—play video games. Little did I know that video games could put Blaine in a position to lead, communicate, and share his latest advances. This freedom placed him in a advantageous spot to take risks, get out of his comfort zone, and exert energy, which otherwise would be challenging to do. And who knew I’d learn in Beetlejuice that in order to get a cloud to move, I had to get a skeleton to shoot a fireball at a beehive?

In the case studies above, parents and/or trainers with high hopes of helping a child created expectations. Although the intentions were positive and constructed to elicit healthy behavior, two critical components were missing: the child and the needs of the child. Once communication became the primary mover, brute demands vapored into meaningful dialect.

As seen by Brian, Ahleiah, and Blaine, once I listened and tweaked the approach based on what I heard, hostility and disinterest switched into reception and engagement. Naturally, they were willing to step outside their comfort zones and try new things (meet expectations in an alternative way) with great effort because my message remained the same throughout: I’m listening, I respect your interests, and I value you. Ultimately, our expectations have a huge impact on our children and have the power to accelerate or decelerate our efforts. So, the next time you create an expectation for your child, be sure to analyze and reanalyze before presenting. What exactly are your words and actions communicating?

2 Comments