I’ve always loved lifting weights, but it’s a love that, for years, has come with a price I haven’t enjoyed paying. Like most guys who get hooked on lifting, I started out with the typical plastic and sand Joe Weider set in my basement, but back in the late 70’s and early 80’s – I’m forty now – I never really gave any thought to using weights to improve my athletic performance. I had no idea what I was doing, and I was more concerned with playing team sports – basketball and football – than I was about using non-specific external methods to actually get better.

Still, I loved the way lifting made me feel.

When I started playing college basketball and finally figured out that spending time in the weight room could help my career, I frequently found myself more concerned with my lifting numbers than with the scoring and rebounding stats I was putting up on the court. Don’t get me wrong here – I love basketball, and until my career ended, I had played the game for my entire life. In fact, I was a starter for one of the best high school teams ever to come out of New York.

For my first couple of years in college, our team didn’t have a strength coach. I knew I had to lift in order to compete, but I hadn’t yet figured out the concept of dynamic correspondence, and had no idea how to go about putting a program together. With zero guidance and a coaching staff that paid no attention to off-the-court training, I followed what I suppose you could call a basic bodybuilding template, which did next to nothing for me athletically.

After a while, though, I started realizing that getting stronger – just getting my entire body stronger overall – would translate to positive results in my sport better than my constant half-assed efforts at increasing hypertrophy. I concentrated on the basics - bench, squat and deadlift – and my numbers started to rise.

Once I started lifting like this – I mean, really lifting – I couldn’t get enough of it. After a while, I didn’t even want to go to my basketball practices anymore. All I wanted to do was get in the gym and put in the work to get my totals moving northward. Basketball started pissing me off after a while, because I’d be so beaten up midway through the season that I couldn’t lift nearly as hard or as heavy as I wanted to.

Nothing, short of maybe sex – with the keyword here being maybe – could take the place of setting a new PR under the bar. There was one problem with all this, however, and it was one that, for a long time, I was afraid would keep me from ever getting seriously strong:

I’m 6’7”.

I’m also an exceptionally late bloomer in terms of “filling out.” I was still relatively rail-thin when I finished college. In fact, I didn’t figure out where my competitive powerlifting weight really needed to be until a little over a year ago, when Dave Tate told me, at a seminar in front of thirty people, that I needed to weigh 375 lbs if I ever wanted to be a world-class lifter. As my good friend and business partner The Doorman can attest, I’ve spent most of my waking hours over the past year taking Dave’s advice to heart.

As a taller athlete, I’ve had to overcome quite a bit to get my numbers where they currently are. I’ve found that conventional programs, as well thought out as they may be, are typically designed for lifters with average frames. By “average,” I mean lifters at least six or seven inches shorter than I am. I’ve found this to be extremely challenging psychologically, because I’ve had to tweak my lifting cycles and make significantly more biomechanical and programming accommodations than most. Every program needs to be individualized, but for the taller athlete this sort of custom tailoring often has to be taken to the extreme.

Since my lower back has always been a major issue because of my height, I’ll start this series off with an examination of how I’ve improved my deadlift. About eighteen months ago, I could barely lock out 600. I know gym lifts don’t count for much on this site, but I nailed my first 700 last week, which is quite an accomplishment for me considering how much “mental rent” I’ve had to pay in finding my way there.

Technique

That fact that I’m a longer-limbed athlete puts me at a great disadvantage in terms of using any kind of leverage when deadlifting. On bad lifts, everything is exaggerated because my bar path is longer with regard to the relationship between my lower back, my hips and my quads. My hips rise first, my quads never fire, and I look like a human question mark – which leads to either various kinds of hitching, or simply missing the lift altogether.

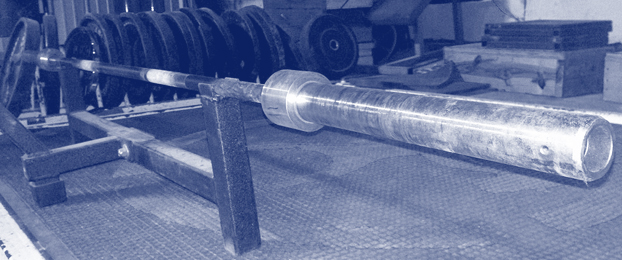

About six months ago, I started lifting from an adjustable platform I built. It raises me anywhere from three to five inches off the ground, and it’s designed in such a way that it’s easy to attach bands to the bar. When you watch most taller guys perform this lift, they tend to turn it into a stiff leg deadlift about halfway through the movement. This is because they try to fire their quads and incorporate their lower back separately instead of in concert. Doing the majority of my max effort work on this platform has effectively conditioned me to fire my quads and lower back simultaneously.

I’m not a big advocate of sumo deadlifting for taller lifters. I’m way too tall for it myself, and I don’t think this has anything to do with any weak points. The sumo stance forces me to “tilt” my upper body too much toward the bar, and it leaves me in a position where I find it impossible to get my hips underneath me.

Training Cycle

Unlike The Doorman, who has worked himself up to some very respectable deadlift numbers by rarely ever deadlifting, I thrive on volume. I’ve manipulated my cycles every way you can imagine, and I’ve found that increasing the volume and frequency of my deadlift workouts has been huge for me.

I do “official” max effort deadlift work once per month, substituted for a max effort squat day, which means my squat-to-deadlift ratio is 3-1. On dynamic effort lower body days, I’ll get on the platform after my DE squats and do 3-4 sets of 10 deadlift reps, at 50% of my DL max with either bands or chains. These are done relatively quickly, with an emphasis on conditioning myself to fire my quads and lower back at the same time.

When I’m squatting on max effort day, I’ll occasionally throw in 3-4 sets of deadlifts at 80%-90% of my max if I feel really good. This may happen once or twice a month - and never the week before or the week after deadlifting on max effort day. In fact, I usually don’t deadlift at all – speed or otherwise – the week before a max effort deadlift day.

Workout Sequence

First off, taller athletes need to warm up like crazy before deadlifting. This is true for me, and it’s true for everyone I’ve ever spoken to who’s my height or taller. I’ll typically spend about twenty minutes on the treadmill, then spend another twenty minutes doing ground-based dynamic movements to warm up my lower back and hips. If I’m feeling tight, I’ll do a lot of warm up sets to work up to a max triple or single. If I’m feeling good, I’ll jump up quickly. Generally, the taller you are, the longer this will take because it takes so long for taller athletes to get comfortable.

Unless I’m taking a max off the floor, I always deadlift off the platform, and I always have some kind of band or chain weight on the bar. Occasionally, I’ll do reverse bands. I’ve completely eliminated partial deadlifts from my program because locking deadlifts out has never been a problem. The use of significant amounts of band tension from the platform has improved my lockout ability while simultaneously conditioning my body to act as one cohesive unit.

Accessory Work

I do a ton of work for my lower back – more than most shorter guys will typically do. Every lower body workout has at least two separate exercises geared toward my lower back. These include good mornings, hyperextensions, banded 45-degree raises and stiff leg deadlifts. On my DE lower days, I try to work in some moderate to heavy good mornings. On heavy deadlift days, I’ll do banded 45-degree raises. I throw in some glute-ham raises when I’m not feeling tight, but my leverage on them is horrible. One of my main goals in the next year is to drastically bring up my hamstrings.

For my abdominal work, pulldown abs have been a staple for the past year. I like to do the rest of my work on the floor, doing movements where I can roll my hips forward and take the arch – I call it the “air pocket” – out of my lower back. This gives me the feeling of taking all the stress out of my spinal erectors. What I’m looking for here is the feeling of having this stress go from my abdominal muscles straight down and through the floor, instead of having it stop at my lower back and put stress on my arch.

As I’m starting to prove to myself, being tall(er) is not the end of the world for a powerlifter. It takes a lot of time, dedication and consistency, and it’s a constant chess game you have to play against yourself and against the bar, but it’s a game you can win if you take the time to learn how to piece your program together.

Kenny Hinchman is the co-owner, along with EFS staff member The Doorman, of East Coast Athletic Development in West Babylon, NY. East Coast Athletic Development is Long Island’s premier Soviet and Eastern Bloc-influenced “Darkside” training facility, with clients ranging from high school athletes to the professional ranks. For more information, visit their website at www.eastcoastathleticdevelopment.com.