For me, the barbell is the heart and soul (as well as one of the most critical purchases) of a home gym, but you wouldn't think that when you look at some of the bars at my local facilities.

Recently I was in the market for another barbell for my home setup, and at the start of this journey, I thought all barbells were equal. I couldn't have been more wrong. I was bombarded with so many options I couldn’t begin to decipher which was right for me, with some websites offering hundreds of different brands and specifications. After spending a significant amount of money on equipment, I thought it judicious to write an article on how to avoid the pitfalls that befell myself when choosing an ideal barbell.

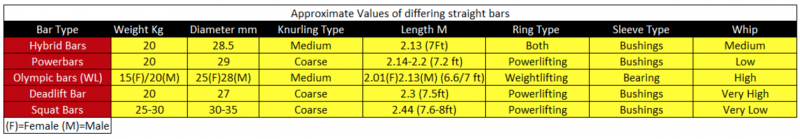

Barbells can range from under £100 for a no-name Chinese import, to well over a £1100 for a top-end Eleiko or Ivanko competition approved barbell. How do you work out what you need and the key differences between various bars? To explore this further, first I think it prudent to briefly describe barbell anatomy and the functions they provide.

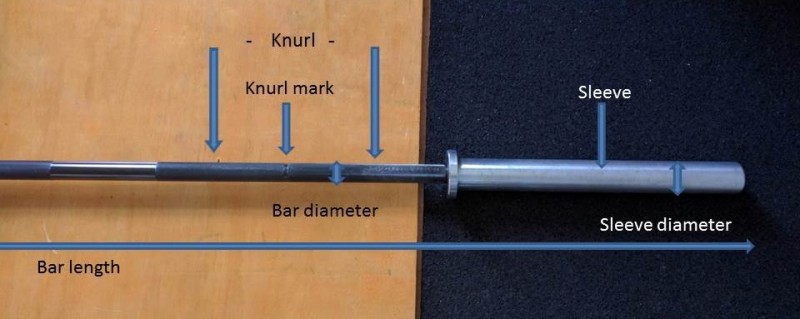

Sleeves

These are "the ends of the barbell’ where the weight is loaded. However, it is worth noting that sleeves can come in one-inch or two-inch widths. This measurement relates to the diameter of the hole through the weight plates that would be loaded onto the bar. All professional barbells are made for two-inch plates, which is what we will be discussing today.

Length

Usually, the size of the bar is listed from end to end, but you can also see listed "loadable sleeve length" which is simply the length of the sleeve. This tries to give you an idea of how many plates you can load on each side.

Bushing/Bearing

Simply put, these allow the sleeves to spin. A bushing is a cylindrical tube that fits into the sleeve to lower friction. These can be lubricated and are usually considered a more durable option, but that’s open to debate. These bushing sleeves also come in a range of materials, which can influence cost quite dramatically. The needle bearing bars have long cylinders that rotate inside the sleeve, reducing friction. These are normally much more expensive and mainly seen in Olympic bars, as they benefit from more spin. Some say bearing-based bars are less durable than bushings, but that might simply be down to lower quality bearing bars letting the system down, as a precision needle bearing is harder to manufacture and has much finer tolerances than a bushing bar.

It’s also worth noting that it has been said a good quality bushing bar can spin as well as a bottom-end bearing bar. Spin is more important in Olympic lifting, as the lifts have more of a speed element and require you to get under the bar quicker, so how quick the bar rotates is important to reduce torque. In powerlifting, the movements are slower and more strength-related, so the need is greatly reduced.

It’s worth noting that you technically can use ball bearings, but these usually cannot handle large radial loads and are for the most part avoided. There are also hybrids of both systems, but these are usually only present with less reputable brands. So if a bearing system is a must (which it isn’t in most cases) buy a quality brand. If they are a very reputable brand, and they use a different system than the above for their barbell, it will usually be fine, as they would not want to damage their reputation. This will normally ensure higher quality parts are used, increasing the durability and spin of the bar.

Knurl

Knurling is a manufacturing process whereby a pattern is rolled into the material, which allows both hands and fingers to get a better grip on the object (in this case, a barbell). It is important to note that the aggressiveness of the knurling can vary quite dramatically, from very aggressive and quite painful, to rather smooth, passive, and more comfortable. Some bars also have a center knurling, which allows more grip on the back during a low bar squat, but can also graze your legs during a deadlift.

Typically an Olympic lifter won’t like an aggressive center knurl, as it can cause irritation on the chest and neck in competition movements (and variations of). However, it is worth noting that a very aggressive knurl may be a bonus for deadlifting, as it will negate the need for chalk in some instances.

Knurl Marks (Rings)

These smooth marks indicate the maximum legal length in powerlifting (IPF, 32 inches apart) or Olympic weightlifting (IWF, 36 inches apart).

Whip

Whip refers to the amount of bend and movement a bar will present under load. A prime example of whip is observed during Olympic lifting; as they power the bar up off the floor and drop down underneath it, the bar can be seen to bounce and flex once the front squat part of the movement has been locked out. You can also observe whip during heavy deadlifts, also referred to as "slack" or "pulling the slack out of the bar" where the bar itself bends before the weight comes off the floor.

Tensile Strength

Correctly termed as “ultimate tensile strength”, this is the measurement of the maximum amount of stress a given material can withstand before breaking. For obvious reasons, we can see why we would want to know the maximum load a barbell can withstand before failing. This is measured predominantly with the SI (international system of units) unit pascals (more often megapascals, or MPa). However, it’s worth noting the American unit differs, and is pounds per square inch (PSI). You should always double-check what unit of measurement your manufacturer uses when looking at the tensile strength of a bar. For this discussion, we will use PSI.

Anything over 185k PSI (185,000) is considered a good quality bar. However, some cheap brands seem to report very high tensile strengths, which highlights an issue: tensile strength doesn’t necessarily translate to bar quality. For instance, I’d rather go with a much-respected brand offering a lifetime warranty at 190k PSI tensile strength, over a no-name-brand offering just 12 months warranty at 205k PSI tensile strength.

End Caps and Fixings

This is the point where the sleeve attaches to the bar, fixing it into place. I personally like the end caps with circlips that allow access to the bar internals (bearings or bushings) should they require greasing or servicing. I’m not a fan of these new sealed units. Even though the companies claim they are just as good, I notice they don’t carry the same length warranty, which concerns me. Hex bolts are the most common but I have yet to see many quality bars use these; they always seem to be present in the lower entry examples.

Coating

I find that if the bars are oiled and maintained, it won’t really matter. Oxide or zinc coats tend to rub off on the racks and, in my opinion, start to look scruffy. Stainless bars would be nice but very expensive. If you live near the sea, stainless bars or coatings are good ideas to limit salt and oxidative issues.

It’s worth noting that I won’t be covering specialty bars in this article. They have their place depending on what system you are running but it would take too long to list. The pros and cons of specialty bars are outside the scope of this article.

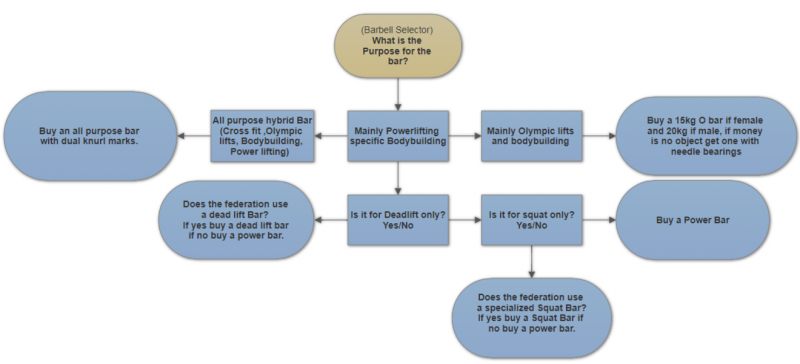

[Click image to enlarge]

What Bar Is Right for You?

In short, due to the law of specificity, you want a bar that closely matches the bar you will be using in competitions (if applicable). There is nothing worse than spending £600 on a 30-millimeter squat bar only to realize on game day that the federation uses a 35-millimeter and it feels very alien, throwing off your performance and costing you the medal.

If you're into powerlifting you will want a bar as close as possible to the one that your federation uses. If you are going into an IPF affiliate, the choice is pretty easy: it will be a power bar to the specification they use. One thing I like about the IPF is that they use the same power bar over three lifts, instead of having two to three different bars. If money is no object, buy the same bar they use at their competitions. These can cost thousands, however, such as the Eleiko competition power bar.

The second less costly option would be to look at your federation's approved list and pick up something there instead. These are usually bars that very closely mimic the competition bar but are not the exact bar you will be using. The price for these can be well under half what you would pay for an official competition bar. Finally, you have the third option: if the above two are still too expensive, you can buy a bar that is to the same specifications as published in your federation's rule book. Most federations will have women use the same 20-kilogram bar that men do, but it is worth double-checking this to make sure before you purchase a bar.

If you’re not in the IPF, there could be up to three bars used across the lifts. These are seen in federations such as the WPC, GPC, and so on:

This is a tricky one. I originally bought a hybrid bar that had a little more whip, but in the end, I just ended up getting a power bar, as it was more specific to the sport and felt like a better compromise. The bench bars are not popular yet, so they are not worth investing unless you are sure you will be using one for your competition.

Again, if money is no object, feel free to buy all three. But if it is, I would just look into the power bar. It’s also highly recommended you check all bar recommendations. For example, the squat bar specifications for some federations may allow up to a 32-millimeter diameter but the GPC allow up to 35 millimeters, which can change the feel of the bar and movement significantly, especially compared to a 28.5-millimeter hybrid bar. As diameter of the bar affects whip, the difference in movement across the barbells can also significantly differ from one another.

In the IWF (International Weightlifting Federation) there will be two main bars: the male (20 kilograms) and female (15 kilograms). The cost of your bar will primarily be influenced by budget. It’s recommended if money is no issue to get a bar with needle bearings, as these barbells will more closely imitate competition bars and the spin present on them. You can, however, get training bar versions if funds are limited with bushings that would suffice for basic lifting. If you are a professional high-end athlete or wanting to get every last edge you can in training, it would be prudent to purchase one that feels like the competition version so you can at least get some bar specificity within your training.

There are good brands that are significantly cheaper with good needle bearings, so do some research.

CrossFit

A CrossFit bar is a bit of a mystery. Looking into the bars typically used, they seem to favor a hybrid bar in most boxes.

To further complicate issues, they have used both men (20-kilogram) and female bars (15-kilogram) for women in competition, so make sure to double-check. They also introduced a C-70 last competition, at 16 kilograms. This oddball is a shortened hybrid bar with a tiny length of 5.75 feet rather than 7.00 feet, to allow more competitors in a given area due to closer spacing. I spoke to Rogue and they didn't confirm that this is a permanent replacement. Caution should be exercised, as due to the length it won't fit many racks, and with only 12-inch sleeves you're not getting a lot of weight on there, especially if using thicker bumper plates. So my advice would lean more toward a general 20-kilogram hybrid bar in this instance.

If you are a female and cannot lift 20 kilograms then get the 15-kilogram hybrid, or maybe a bearing bar if you fancy an IWF competition in the future.

Bodybuilding

Well, you can use most bars for this. A hybrid bar is nice if you’re adding a few Olympic lifts in. However, if you are a very heavy squatter and you find the whip annoying or unsafe, you might want to consider a power bar to try to lessen the amount of whip present at the higher loads. I have squatted with a hybrid bar and the level of whip is pretty noticeable. I don’t mind the bounce too much, but having a power bar just to be on the safe side when heavier weights are approached may be the best course of action. It’s also worth highlighting that if you ever intend to do a powerlifting meet in the future, you might as well start with a power bar.

Specifications of the bars are provided in the two tables within the article. These are approximations, so please verify your federation specifications before buying.

Russell Taylor began coaching professionally in 2014. Since that time, his evidence-based approach has had a string of top placing client male and female finishers in everything from physique to powerlifting. He has also has achieved a submaster deadlift world record in the WPC and a national deadlift gold medal in the UK. His ultimate goal is to unify the industry by combining academic evidence with practical experience.