As a strength and conditioning coach, our goal is to not only make our athletes bigger, faster, and stronger but to make them better movers in time and space. In order to become better movers, athletes need to learn and understand their bodies and know what feels good and what does not respond well with their bodies. Cam Davidson’s approach to training athletes is based on making the athlete “feel” everything such as feeling that weight at the bottom of a three-second pause squat or feeling the eccentric load on a bench press.

Jumping repetitively for a rebound in basketball or taking that penultimate step into a spike in volleyball, all athletes need to be explosive. The question becomes what is the most effective way to train explosiveness in the weight room? Keeping in mind that what we do in the weight room needs to also translate to the athlete’s specific sport. Many coaches use sprints, jumps, and throws to build explosiveness and force in athletes at the high school level. While jumping, sprinting, and throwing are all important movements, I would argue that there is a complex of lifts that, done correctly, can improve an athlete’s peak force, rate of force production, and explosiveness. It's called Olympic weightlifting.

MORE: Olympic Weightlifting for Strongman Athletes

Most young athletes do not begin Olympic lifting until college, but the benefits that it has and the translation that comes with Olympic lifting bars none. The ability to train brace development, force development, neurological adaptations, and novelty in the programming solicits different avenues of approach in developing young high school athletes.

Brace Development

Bracing is one of the most important skills to hone in athletics. It builds coordination within the body to know when to brace and when to relax through the lift or a sprint. Diaphragmic breathing is key when learning how to brace. The ability to fill the diaphragm and create tension within the body will stabilize the body when handling heavy loads.

On the setup of a clean, an athlete grips the bar, creating tension on the bar by filling the belly with air. Performing a clean requires one to move from a tight position, gradually increase speed on the bar, and explode and catch the bar in a front rack position. From the floor to the moment before the athlete performs the clean, the athlete is constantly tight while keeping tension within the body and contracting their muscles.

The moment the athlete cleans, the body cannot be completely rigid and in a contracted state on the catch because the athlete 1) will not have enough relaxation to catch the weight with heavier loads and 2) will lose bar whip on preparation for the jerk. In the split second where the clean occurs, the athlete has to allow the body to relax in order to allow the body to give on the catch in the front squat position, and then contract again when performing the front squat. The catch portion of the clean is where the brace development occurs because the body has to be able to be in a strong position to receive the weight of the barbell. The constant back and forth between contraction and relaxation during the clean is indicative of understanding the timing and technique of a clean and the body making those neurological connections of when to brace and when to relax.

The ability to rapidly undergo extension and flexion will allow athletes to improve their agility. Agility is defined as the ability to accelerate and decelerate constantly. When we look at athletes in cutting sports such as football and basketball, oftentimes they need to run to a spot as fast as possible and decelerate quickly to move to the next spot. The same concept can be applied in a clean and a snatch. The transition from accelerating the bar from the floor to decelerating the bar on the catch, to then accelerating the bar on a jerk creates more body coordination from the brain to the muscles needed to complete the lift and emphasizes where exercises performed in the weight room translates to their actual athletic performance.[1]

Force Development

Force is everywhere in sports—the amount of force an athlete can produce to hit another player on a football field or how much force an athlete can produce to smack a baseball out of the park. One of the seven power development factors is the rate of force development (RFD) which, according to Owen Walker, is a measure of explosive strength and how fast an athlete can produce force. The ability to create force under load at rapid speeds allows for the athlete to improve their other abilities needed in sport. Most well-trained athletes that incorporate Olympic lifting into their programming yield better results on their jumps, sprints, and throws.[2] Olympic lifting tends to create more explosive force in comparison to other bilateral lifts such as a back squat or a deadlift due to the ballistic speed on the bar.

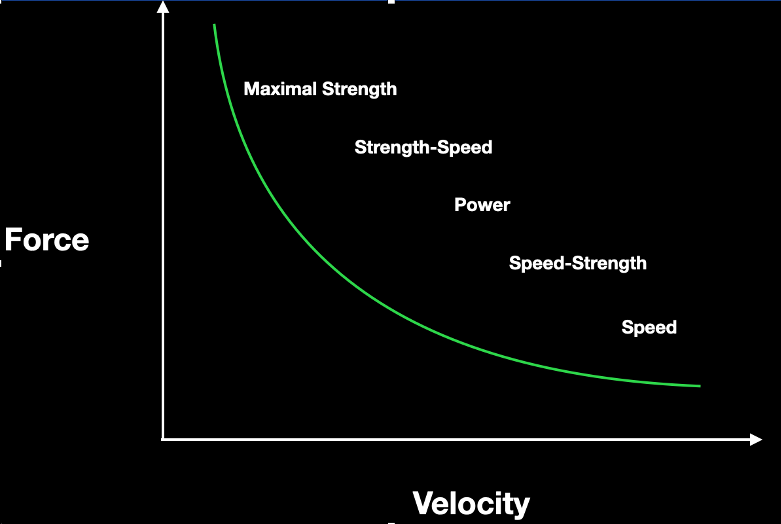

Now, as strength and conditioning coaches, we all know that building the perfect athlete is near impossible. It is our role to evaluate our athletes and strengthen their strengths and correct their weaknesses so that they have the abilities needed to perform at a high level. The force-velocity curve is a physical representation on the inverse relationship between force and velocity and how both factors intertwine with each other.[3] When evaluating Olympic lifting and programming for high school athletes, the goal is to complement their movements with the exercise done in the weight room. For an outside linebacker in football, I would want to program him upwards of the strength-speed mindset. Whereas, for a triple jumper, I would program them with speed-strength in mind due to their respective sports.

Neurological Adaptations Through Timing

As I briefly mentioned earlier, the timing and technique portion of Olympic lifting requires a cognitive connection from the brain to the applied muscle groups. According to Joel Smith, the qualities of a fast athlete are strong, elastic, coordinated, twitchy, extensible, and fast-twitch dominant. To build upon this, Olympic lifting allows for the development of powerful rhythm which is correlated to acceleration or jumping.[4] In order to build the rhythm necessary to jump, sprint, or lift, athletes need to make the neurological connections within their body to allow for optimal performance. The ability to graduate force is critical in performing smooth, coordinated lifting movements.[5] The timing built into performing a clean builds upon the aspect of developing the brain from the first pull, to the second pull, to the catch. Going back to force development and tying neurology together, the force output on the whole muscle is intensified through the increased frequency of the individual motor units applied.[6]

What is the Point?

A lot of science, technical terms, and concepts were thrown at you and you are asking yourself, “What’s the point?” Most high school athletes have never seen the inside of a weight room prior to freshman year. They are at a very young training age and to me, that is an amazing opportunity to develop good training habits to build upon moving forward. I want to reiterate, I am not saying that Olympic lifting is the end-all-be-all. I truly believe in jumping, sprinting, and throwing. However, adding Olympic lifts into high school athletics will improve sports performance on the field.

Furthermore, I believe that exposure creates experience and to not shy away from the inevitable. Most high school athletes that move to the next level in their sport will more likely than not have to Olympic lift. Why not coach and train those movements and patterns at a young training age over the course of four years in high school to provide the best movers in our athletes? As coaches, we need to stop using the mantra “it is too time-consuming” and “it’s too technical to teach” as the pivotal points as to why not to coach Olympic lifts.

We are strength and conditioning coaches in this field by choice and if there is a consideration to improve our athletes at the high school level, then we need to exercise that autonomy and use our knowledge to complement their programming with adding Olympic lifts. Teaching a young athlete how to clean or snatch demonstrates your ability as a strength and conditioning coach to actually coach rather than be a drill coach and put your athletes through cone drills.

Final Thoughts

High school sports is arguably the best time in an athlete’s career to build the best habits. It makes sense to me to provide my athletes with the tools to be better movers on the field. I want to provide them with programs that build basic levels of movement for their given sport—sprinting 100m dash or breaking a cut for a touchdown. Athletes that incorporate a new stimulus and variety of lifting (Olympic lifting) will build their athletic base to build better jumps, sprints, and throws to increase performance overall.

Speed, strength, power, and performance—these very facets of sports are the foundation and root of all athletic development.

References

- Ratelle, Will. “A Case for Training Olympic Lifts in College Athletics.” SimpliFaster, 17 Apr. 2020, simplifaster.com/articles/training-olympic-lifts-college-athletes/.

- Walker, Owen. “Olympic Weightlifting.” Science for Sport, 16 July 2020, www.scienceforsport.com/olympic-weightlifting/.

- Walker, Owen. “Force-Velocity Curve.” Science for Sport, 16 July 2020, www.scienceforsport.com/force-velocity-curve/.

- Smith, Joel. "Speed Strength." CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 2018.

- Larsen, Amber. “The Neurological Benefits of Clean and Snatch Complexes.” The Neurological Benefits of Clean and Snatch Complexes | Breaking Muscle AU, Breaking Muscle, 28 July 2020, breakingmuscle.com.au/au/amp/fitness/the-neurological-benefits-of-clean-and-snatch-complexes.

JuJu is a strength and conditioning coach at Varsity House Gym in Orangeburg, NY. He played for the United States Military Academy with the Army Black Knights as a tight end. JuJu primarily works with high school football and basketball players while assisting with soccer and lacrosse athletes.