The title of this article refers to a pet project of Statistician and Strength Sports Ambassador Herb Glossbrenner (1942-2013), who maintained the “Supertotal” lists between 1996 and 1997. Glossbrenner combined the Schwartz-Malone (powerlifting) and Sinclair (weightlifting) coefficients for each weight class and created a ranking for people who competed in both sports. The top 20 ranked were termed “Supermen of the Century.” The “Supermen of the Century” lists include people like Fred Hatfield (“Doctor Squat”), Bill Starr, Jim McCarty, and—surprise!—Louie Simmons. (Antonio F. Bruno, personal communication, 2018)

Herb Glossbrenner calculated powerlifting rankings and published articles on Powerlifting USA (PLUSA) magazine from 1971 to 2005, when he had a stroke.

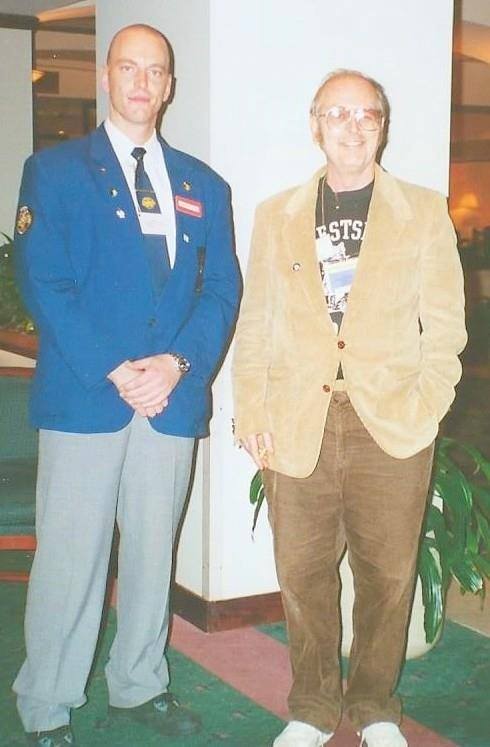

Picture by economist Stef Mattens, responsible, today, for creating and maintaining the strongman world and country rankings

We’ve all heard the question, "who is the strongest?” The truth is that there is no answer to this question because human strength is not one single physiological phenomenon, but many and not necessarily co-occurring. Glossbrenner’s Supertotal, if systematically applied—and if a high enough number of athletes competed in both sports—would provide a list of people who had, at the same time, a high force output, high power output, high rate coding, and high rate of force development. That’s a lot (Moritani 1993, Shemmell et al 2005).

When we look at people who competed not only in two but several sports, some of which require locomotion, rotation, isometric strength and things like kinesthetic awareness, we end up with a list of quite unique individuals. They are not better than athletes who specialize, but they do challenge our accepted view that only specialization can lead to excellence due to the adaptation specificity (Ginsburg et al 2014, Deanna et al 2006).

Marcos, Zatsiorsky, and Transfer

A long time ago, when I was writing about transfer, I chased the origin of the ideas down to Zatsiorky’s first research at the Moscow Institute of Physical Culture. There is no translation of that early work. I wrote to him, as a last hope for access to the birth of this important concept; he sent me what he could, but what I really wanted to read was in Russian. No luck (Zatsiorsky 1960, 1961, 1966, Zatsiorsky and Bushuev 1961, Zatsiorsky et al 1959). Zatsiorsky never gave up on studying transfer (Wu et al 2013, Wu et al 2015).

My point was that opposing the specificity principle and transfer was a false dichotomy. Both exist and both were relevant strength and conditioning training principles. A couple of important research articles were published, such as Carlock and collaborators’ study with weightlifters and the vertical jump (2004). They were concerned with the practical applications of using peak power output-generating exercises (mostly from weightlifting) in the strength and conditioning programs for other sports. Today this is a no-brainer: most coaches agree that weightlifting and/or its partial movements are essential to increased performance in most sports.

I had already exhausted that search when I met Marcos Ferrari, in 2011, and we became friends. He was moving from powerlifting to strongman and, at the time, in Brazil, all we had were educated guesses. The recent literature on the biomechanics and activation pattern in strongman motor tasks suggested that they could transfer and increase performance—both strength and power output—in a number of different motor tasks. Specifically, I believed that they would transfer to the squat and the deadlift.

The one line of research that most interested me concerned the higher demand one sport posed for a set of functions that would improve another sport’s motor task performance, such as the higher core activation of strongman carry events to the squat: “The carrying events challenged different abilities than the lifting events, suggesting that loaded carrying would enhance traditional lifting-based strength programs.” (McGill et al 2009).

At this point, we have two very different types of questions:

- Can training certain motor tasks that are competitive to one sport benefit the athlete in the performance of another sport? This concerns the use of those movements as assistance work and the answer is yes, period.

- Can proficiency in certain motor tasks, skills or functions related to competitive excellence in one sport make an athlete perform better in another or other sports, or is it detrimental? Is it complementary or concurrent? This concerns cross-athleticism, or competitive participation in more than one sport.

Certain sports are based on cross-athleticism and the mastery of more than one set of skills, such as the triathlon, the decathlon, strongman, Highland games, and now Crossfit Games. But do you get better at one by being better at another? Or do you just get “well rounded”?

Marcos Ferrari

Marcos Ferrari had been a successful powerlifter in the 181-pound, 198-pound, and 220-pound classes. In 2011, he showed up at a strongman event just to have fun. He had never handled an Atlas Stone before. There was some confusion in scoring, but if he didn’t win the event, he was second, and there were a handful of participants. Marcos chose strongman as his main sport for several reasons that include his love for it, but also the fact that this choice allows him to be compensated for the time spent on training and competing, not to mention all the other expenses related to elite athleticism. Marcos is a chemist and used to work for SABESP, a Brazilian water and waste management company owned by São Paulo state. With five children, he needed to think about how to cover all the expenses.

What I observed training with him and watching him compete is that, as he developed skill and proficiency in strongman events, two of his lifts improved dramatically: the squat and the deadlift. The bench press also improved, but proportionally less. Precise comparisons are difficult because he also gained muscle mass and weight.

Marcos in powerlifting, 2009 (fully equipped, single-ply):

Marcos in his first strongman competition:

Later in 2011, squat (wraps only):

Marcos in strongman, 2016:

Steve Pulcinella

Below is a testimonial from Steve Pulcinella (italics and bold mine):

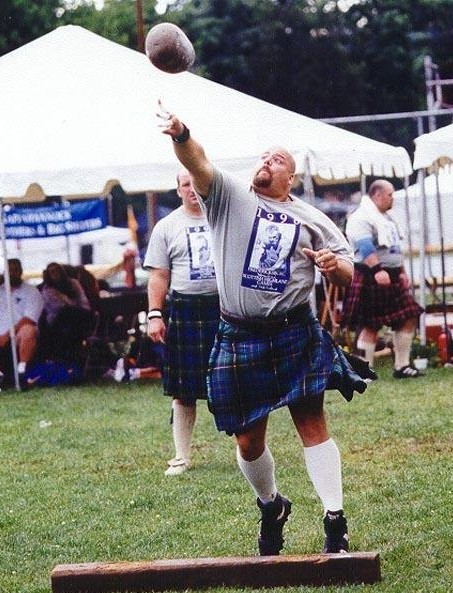

“I was an active powerlifting competitor and track and field thrower throughout my early teens and 20s. In my late 20s I began doing strongman contests and almost at that same time I started competing as a Highland games athlete. After competing in the 1994 World’s Strongest Man contest I shifted my focus to Highland games because I just didn't have the size or the desire to 'enhance' my strength artificially to be competitive at the top level of strongman. Luckily for me I had a pretty good natural knack for throwing that I rose quickly in the pro ranks and became one of the top pros for a while.

In the very prime of my competitive years (between 30 and 40 years old) I also was holding down a 40-hour per week full-time job, I had started Iron Sport Gym and was there another 40 hours a week, had full custody of my two young daughters, and was still competing all over the world at least 20 times a year. I was a really busy guy, to say the least. There had been times when I would compete in different sports at the same time. One time I even did a full seven event Highland games on Saturday and lifted in a three-lift powerlifting meet the next day. There were a few years where, in the same year, I had done a powerlifting meet, a pro strongman contest, a pro Highland games, and an open track meet. That wasn't uncommon for me. I was always game to show off my strength and test myself.”

Shawn Lattimer

Shawn Lattimer is a former super heavyweight powerlifter (primarily bench specialist, equipped), competed from 1996 to 2008, and was the fourth man in the world to bench over 800 pounds and fifth man in the world to bench over 900 pounds. He has a best bench of 905 pounds. He is a former member of Metal Militia. Shawn currently competes in armwrestling since 2008 in the super heavyweight class. He is a five-time national champion and ranked top 10 left hand in North America continuously since 2010. He is co-captain of Team NJ Armwrestling.

His testimonial (italics and bold mine):

"For a little bit I switched back and forth between lifting and armwrestling. The two are not very compatible from a training and recovery standpoint, meaning I couldn’t train and compete in both concurrently and be very successful. Switching to powerlifting for six months and back to armwrestling for six months actually worked pretty well. I was able to recover from one sport while doing the other.

In general, I think many strength sports have enough training overlap that a competitor can be successful at two. MAS wrestling, armlifting (grip competition), powerlifting, armwrestling, strongman, and tug of war all share similar strength requirements and similar exercises. If an athlete was to divide their year into two 'seasons', one for each sport, I think he or she could be successful. Definitely not something for novices; this would depend on already having a reasonable mastery of both sports in question. A novice trying both could easily expect poor results from both.

The issue I see is when an athlete tries to contest two sports effectively simultaneously. The divided attention and divided training leads to less than stellar results in both sports. The single-minded drive and determination required to truly perform at peak power gets watered down. More than two sports? Probably way too much for anyone except a truly amazingly gifted athlete."

William Lee

William started playing baseball at age six and continued to do it until he was 18 and out of high school. He also practiced martial arts as a child. Once in middle school, things started to get busy for him: besides baseball, he started to play football, basketball, and golf. By the end of his sophomore year he joined the wrestling team. Then he grew up and grew big. He started seriously strength training and the plan of going to college on a baseball scholarship changed to football. It was during college that he got bitten by the iron bug and participated in a few unsanctioned bench-press meets. In 2003 William participated in his first official powerlifting meet and also his first strongman competition.

His testimonial (italics and bold mine):

"2004 and 2005 were strictly powerlifting competitions with intermural softball added in. 2006 to 2008 I would compete in powerlifting, and Highland games. 2009 was an off year competing in Highland games and starting softball again. 2010 I returned to the platform for powerlifting with bench-only as well, softball, a local strongman event, Highland games, and competitive shooting. 2011 I competed in my first, only, and maybe last bodybuilding show, cutting from 280 to 240, another local strongman event, competitive shooting, powerlifting, and Highland games. 2012 to present I have continued to compete in powerlifting, Highland games, and shooting."

William has a preference for being a well-rounded and overall strong athlete rather than an elite one. He explained that, although he did win several titles, he was never at the international top of any of the sports he played and plays.

Amit Sapir

Amit Sapir has been extensively covered by the media, including by elitefts. He started his athletic career as a weightlifter, which he had to quit due to a bad shoulder injury. From there he moved to bodybuilding and finally to powerlifting, where he broke four all-time squat records in one year, in four different weight divisions.

In bodybuilding competition:

In powerlifting:

Mikhail Koklyaev

Mikhail Koklyaev is the strict cross-athlete: available records show he kept competing in all three sports (weightlifting, powerlifting and strongman) for at least a decade. He achieved international elite level performance in all three.

Weightlifting, 2005:

Powerlifting, 2012:

Strongman, 2010:

Jón Pál Sigmarsson and Bill Kazmaier

Jón Pál Sigmarsson is the legendary strongman pioneer who died at age 32. He was born in Iceland on April 28, 1960. Jón Pál had a congenital heart disease and was aware that it was lethal. Reading about him and watching the documentary on his life, it’s hard not to consider that he was in a hurry to live as fully as possible. Bill Kazmaier was his contemporary, adversary, also a legend, and crossed powerlifting and strongman for many years.

Jón Pál powerlifting:

Jón Pál bodybuilding:

Jón Pál armwrestling:

Jón Pál strongman:

Bill Kazmaier powerlifting:

Bill Kazmaier strongman:

Bottom Line

Is cross-athleticism a good thing? That depends. For children, with all the caution we must have with competitive participation for them, sure. Cross-athleticism builds motor repertoire and the best age do to that is young. But the child athlete is not the adult athlete and cannot be subject to the same risks and pressure (Brylinsky 2010, Balyi et al 2013).

Is cross-athleticism good for every adult strength athlete? No. Very few can carry over their acquired skills and increased functions to another sport. For elite athletics, the rule is specialization. Few people are naturally talented for elite participation in more than one sport, but some are. As in any elite-level activity, these people are special and rare. There is no systematic data on this, but it seems that usually those who are excellent both in weightlifting and powerlifting, for example, have started off as weightlifters. These people are so rare that all we have are potential case studies. This is not bad; case studies are also studies. All we need to do is convince them to let us biopsy them (just kidding).

They are rare and they are awesome, and awesomeness is always cool. They are the closest thing we have to real supermen.

References

- Balyi, Istvan, Richard Way, and Colin Higgs. "Late specialization is recommended for most sports" in Long-term athlete development. Human Kinetics, 2013.

- Brylinsky, Jody. "Practice makes perfect and other curricular myths in the sport specialization debate." Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 81, no. 8 (2010): 22-25.

- Carlock, Jon M., Sarah L. Smith, Michael J. Hartman, Robert T. Morris, Dragomir A. Ciroslan, Kyle C. Pierce, Robert U. Newton, Everett A. Harman, William A. Sands, and Michael H. Stone. "The relationship between vertical jump power estimates and weightlifting ability: a field-test approach." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 18, no. 3 (2004): 534-539.

- Deanna, L. A. et al. Motor training induces experience-specific patterns of plasticity across motor cortex and spinal cord. J. Appl. Physiol., v. 101, p. 1776–1782, 2006.

- Ginsburg, Richard D., Steven R. Smith, Nicole Danforth, T. Atilla Ceranoglu, Stephen A. Durant, Hayley Kamin, Rebecca Babcock, Lucy Robin, and Bruce Masek. "Patterns of specialization in professional baseball players." Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 8, no. 3 (2014): 261-275.

- McGill, Stuart M., Art McDermott, and Chad MJ Fenwick. "Comparison of different strongman events: trunk muscle activation and lumbar spine motion, load, and stiffness." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 23, no. 4 (2009): 1148-1161.

- Moritani, Toshio. "Neuromuscular adaptations during the acquisition of muscle strength, power and motor tasks." Journal of Biomechanics 26 (1993): 95-107.

- Shemmell, Jonathan, Matthew Forner, James R. Tresilian, Stephan Riek, Benjamin K. Barry, and Richard G. Carson. "Neuromuscular adaptation during skill acquisition on a two degree-of-freedom target-acquisition task: isometric torque production." Journal of neurophysiology 94, no. 5 (2005): 3046-3057.

- Wu, Yen-Hsun, Nemanja Pazin, Vladimir M. Zatsiorsky, and Mark L. Latash. "Improving finger coordination in young and elderly persons." Experimental brain research 226, no. 2 (2013): 273-283.

- Wu, Yen-Hsun, Thomas S. Truglio, Vladimir M. Zatsiorsky, and Mark L. Latash. "Learning to combine high variability with high precision: lack of transfer to a different task." Journal of motor behavior 47, no. 2 (2015): 153-165.

- Zatsiorsky V.M. (1960) Transfer of training - one of the main problem of the theory and practice of physical education. Theory and Practice of Physical Culture., v. 23, #9, pp.652-658 (In Russian)

- Zatsiorsky V.M. (1961)b Training of motor abilities of athletes. Moscow, Central Institute of Physical Culture (In Russian)

- Zatsiorsky V.M. Motor abilities of athletes. Moscow, FiS Publisher, 1966 (1-st Edition) and 1970 (2-nd Edition), (In Russian)

- Zatsiorsky V.M., Bushuev V.G. (1961) Contemporary training methods of elite weightlifters. Theory and Practice of Physical Culture. 1961, v. 24, #6, pp.443-446 (In Russian)

- Zatsiorsky V.M., Volkov N.I., Fruktov A.L. (1959) The study of the transfer of training in race walking and running. Theory and Practice of Physical Culture, ,#10, pp.759-763 (In Russian)

Acknowledgments

Stef Mattens, Steve Pulcinella, Shawn Lattimer, Joe Roark, William Lee, Dave Tate, Antonio Ferraro Bruno, and Marcos Ferrari.

I swear I had written a full reply to your comment, but the Internet ate it. With your impressive bio as a S&C coach, I think reaching an elite total is "cool", but far less important than what you are doing right now. By becoming proficient in the execution of other sport-specific motor tasks, you are improving the exercise and tool library for your athletes and military servicemen. You have powerlifting, weightlifting and "odd objects" (strongman) there already. Your people are lucky. Congratulations, sir!

Marilia