Recently, I've been thinking a lot about confirmation bias in fitness—how people tend to believe what they already think is true.

We see this a lot with our clients: Client A won't touch a carb because he started eating Paleo and lost weight. Client B hates resistance training because her boyfriend does it, and he looks bulky. Client C insists on HIIT even though it's destroying his joints because of the "no pain, no gain" mentality.

But as fitness professionals, we're smarter, right? We know to look at the studies and to read the journals. We get real results with our clients due to measured, progressive, and intelligent programming. Just look at our list of success stories!

But what if we're victims of a very similar pattern? Let's take a look.

Confirmation Bias—What is it?

Confirmation bias can be defined as "the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories."

There are a couple of issues with that. First of all, any bias makes it difficult to be objective. And when trying to analyze and prepare clients for success, we need to listen to the facts. Plus, thanks to our luck of living in the Information Age, there's SO MUCH new evidence.

RECENT: Your Haters are Pushing You to the Top — Embrace It

And that evidence itself isn't always as objective as we'd like to think it is. To highlight, here are a few of the most outstanding issues:

Problem #1: Our Circles Tend to Reflect Us

Research back in the 60s and 70s (before our social circles were heavily internet influenced), showed that social circles were biased toward similar socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (1). This means that adults tend to choose nearby friends of similar social statuses, ethnicities, and political/religious preferences. Flash-forward to the dawn of social media, and even with modern technology, friendships still tend to be heavily influenced by physical proximity. But still, subjects of research tend to self-segregate according to racial background, gender, and interests (2).

This, of course, makes sense. If we connect with shared traits in people, we're more likely to develop close relationships with them. However, homogeneity of thought, experience, and lifestyle yields bias, which could mean sticking to beliefs that might not work for your clients. Even if you work with a specific niche, each individual is different, and it's YOUR job as a coach to figure out what works best for him or her, not serve up something that's worked well for you or others.

Problem #2: Taking Scientific Evidence as Proof

Good coaches know to investigate the evidence before making a definitive claim. Among scientific research, a systematic review or meta-analysis of randomized, controlled, double-blind trials is about as "gold-standard" as it gets when looking for evidence (3). Unfortunately, those are difficult to conduct, are often tedious to read, and take a LONG time.

They're also impractical when it comes to nutrition and exercise questions. Any coach in the industry knows the difficulty of getting someone to adhere to a diet, even when it aligns with their goals. Now, imagine trying to convince a random group of people to eat a certain way, without fail, for long enough to come to any real conclusions. Oh, and then imagine having to control EVERY OTHER aspect of their lives that could become a confounding variable. It's virtually impossible.

Instead, a lot of lifestyle research is observational—tracking already existing habits and trying to retroactively control for variables that might get in the way. Although this can provide a lot of insight, you tend to run into the old "correlation does not equal causation" problem.

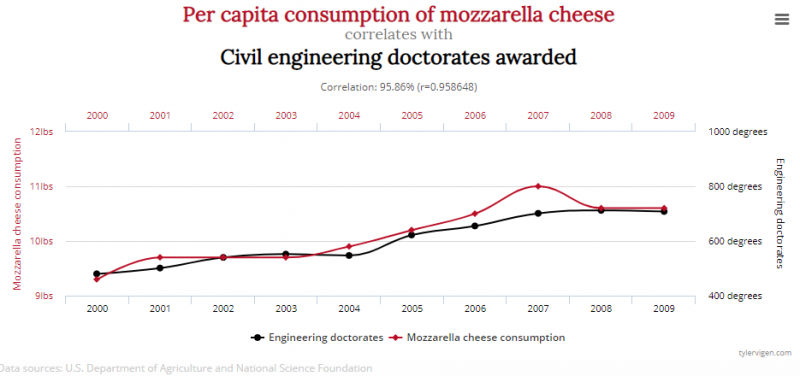

For example, the per-capita consumption of mozzarella cheese each year correlates with the number of civil engineering doctorates awarded (maybe civil engineers love mozzarella cheese?) (4).

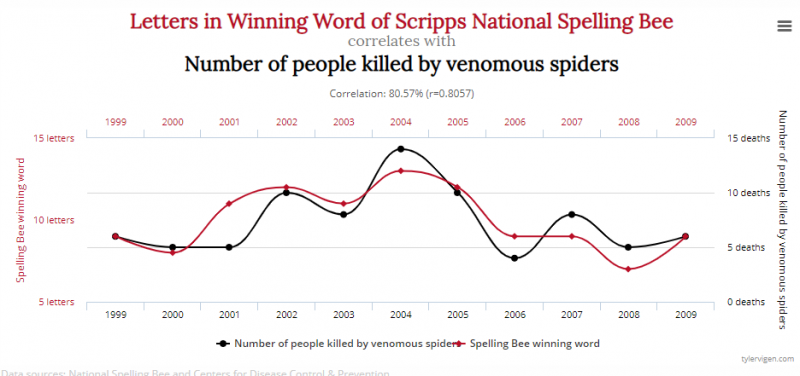

Or the number of letters in the winning word at the Scripps Spelling Bee correlates with the number of people killed by venomous spiders (4).

Although these are extreme examples, it shows that just because two things change at the same level in the real world does NOT mean they're responsible for each other. Although we intuitively understand that certain types of diets and exercises are beneficial, it's tough to prove that one causes the other. That's why we get scientific claims such as red meat causes cancer, then doesn't…(5) or wine both makes you live longer and shortens your lifespan (6). So, it's important to take all of these extreme claims with a grain of salt.

Problem #3: Taking our Successes as Proof

In 2013, Michael Allen Smith, a fitness blogger out of Seattle, Washington, wrote something that caught my eye. In his article, he talks about survivorship bias or coming to potentially false conclusions by simply looking at those who have succeeded. According to Wikipedia, this type of selective thinking happens in evolution, business, military, architecture, and even in history.

Just consider this: How many events in history have been told by the winners? The survivors? The documents that weren't burned, disregarded, or otherwise lost? Those who survived write the story as if it were due to some personal success, touting their own merits while downplaying any failure. It's a dangerous line of thinking that negates a huge part of history.

And it's a dangerous trap for fitness professionals if we're not careful.

By only looking at those who have survived the trials of that one extreme diet, that HIIT program, or that five-day-per-week personal training package, you're unintentionally self-selecting as a coach. Those who didn't make it? It was obviously due to their lack of willpower, not your programming. And those who do spread the word attract like-minded friends and re-affirm your methods.

But is it really the fault of our CLIENTS when they don't meet a certain standard? Of course not. That's literally why they hired a coach because they needed help.

The Bottom Line—We Created this Madness

Now, to sell a book, we have to manipulate studies, cherry-pick them, and then add an extra 100 pages about the magic! There is none. There is no magic about any of these diets. You must reach a caloric deficit to lose fat. But there IS magic to making money and a great success story.

So, the fitness industry slaps a fancy name on a fad; sells a few million copies of a book, diet, or training method; and voila! We market what's POSSIBLE…if everything else falls into place. If you happen to love kale, you can afford not to work two jobs, and you don't have any joint issues. The people who can survive it, survive it, and those who don't…don't. And they're left feeling worse about themselves when in reality, there was another way.

Extremes Sell but Success Lies in the Middle—The Danger of Bias

The fitness industry is called that for a reason, and it's ultimately a way to make money.

Unfortunately, extremes sell.

People want quick fixes that sound exciting. On top of that, things that are selling stir more engagement, gather momentum, and go "viral." And that's how fads get started.

These trends obviously work for some people for some time. But there are scenarios where following the extremes is flat out bad advice.

When we fall victim to confirmation bias, we close the door on other ideas or options that might better fit our particular situations. Here are just a few popular examples:

- Breakfast is the most important meal of the day.

- Six smaller meals need to be consumed daily.

- Intermittent fasting is mandatory.

- Eating at night causes weight gain.

- Protein is bad for your kidneys.

- Sugar is bad.

Let's look at that last one. Objectively, sugar is not bad. It's actually the body's primary fuel source. However, when it makes up the majority of your diet, and you don't move enough, it can easily lead to weight gain.

With intermittent fasting, someone took the idea of skipping breakfast (the most common way to fast…yes, I'm aware there are other ways to do it) and marketed it very well. It stands out! Why? Because breakfast companies spent a lot of effort marketing the idea that the meal, during which consumers ate their products, is the most important meal of the day. So, NOT eating it challenged long-held beliefs, got noticed, and took on a life of its own.

In reality, whether intermittent fasting, eating breakfast, or eating most of your calories at night works for you depends on your lifestyle. They're all just meals. One person might skip breakfast and end up eating less during the ENTIRE day as a result. Another will try to fast and overeat junk food during their feeding window, thus leading to a caloric surplus.

Everyone's lifestyle is different. Maybe I wake up at 3:30 AM and go train members at my gym. Maybe you don't. Maybe you work the night shift or have a set lunch break at noon. Maybe you LOVE your morning cappuccino but could use a little more portion control.

You see, we all have successful clients, ones who struggle, and ones who quit. However, when a client reaches their goal, we're more likely to evaluate what that person did that worked, rather than look at what didn't work for someone else. This means that those who are naturally predisposed to fit an extreme diet will have an easier time.

The trap comes when we perceive the success stories as products of the program we prescribe and the failures as the fault of the client.

So, What Can You Do?

Conduct a thorough audit of ALL of your clients—the ones you've had for years, the ones who quit after two weeks, and everyone in between.

Ask yourself these questions:

- What went well, and why?

- What went wrong, and why?

- When unsuccessful/successful, what are the commonalities in what YOU did?

- What would you do differently in both situations as a coach?

Pay special attention to what happens outside of prescribing a program. People are complex, and real change relies on much more than a cookie-cutter plan. That's the art of coaching, and challenging your survivorship bias can help to set you apart.

References

- Verbrugge, L. M. (1977). The Structure of Adult Friendship Choices. Social Forces, 56(2), 576. doi: 10.2307/2577741

- Lewis, K., Gonzalez, M., & Kaufman, J. (2011). Social selection and peer influence in an online social network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(1), 68–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109739109

- Research Hub: Evidence-Based Practice Toolkit: Levels of Evidence. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://libguides.winona.edu/c.php?g=11614&p=61584

- 15 Insane Things That Correlate With Each Other. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations

- Kolata, G. (2019, September 30). Eat Less Red Meat, Scientists Said. Now Some Believe That Was Bad Advice. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/30/health/red-meat-heart-cancer.html

- Chodosh, S. (2019, March 18). Remember when a glass of wine a day was good for you? Here's why that changed. Retrieved from https://www.popsci.com/moderate-drinking-benefits-risks/

Header image credit: ANDREI BANDARCHYK © 123rf.com

Detric Smith (CSCS, ACSM EP-C, PN-1) is the owner of Results Performance Training in Williamsburg, Virginia. He has over 18 years of experience as a personal trainer. You can read more about his work at detricsmith.com and reach out to him with questions at facebook.com/detric.smith.

I've been thinking a lot about a corollary perspective when it comes to our own diet and programming. Because we fight to minimize cognitive dissonance, it almost always leads us to think that our current training and nutrition are ideal. It's only in hindsight that we're able to see areas where we had room to improve.

All the more reason to hire an objective coach in the pursuit of constant improvement.