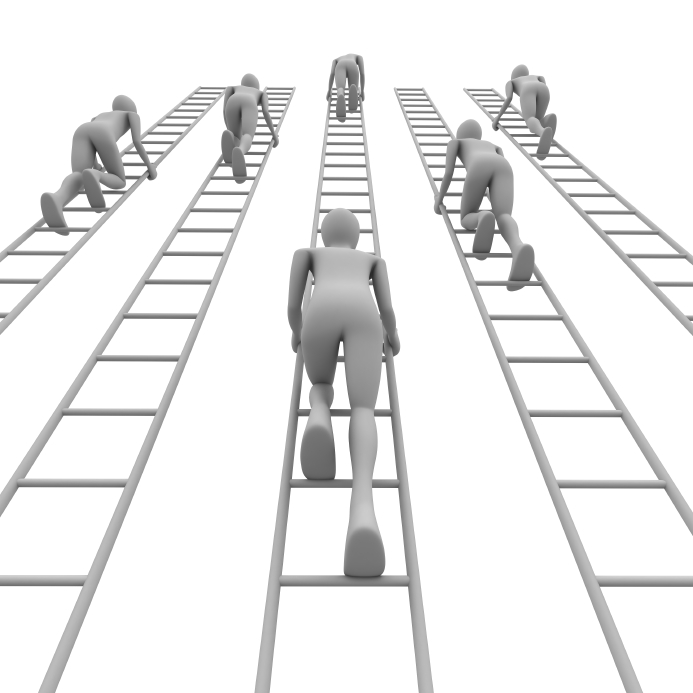

For strength and conditioning practitioners of any type, there is a lot of information that comes out. At the 2005 CSCCa conference in Salt Lake City, UT, Buddy Morris once said that information in improving strength and conditioning doubles every 18 months , and I’m thinking that might be even faster now, especially since the journal of strength and conditioning research (JSCR) has become a monthly publication. All of this information leads to categories of people: those who ride the pendulum, and those who climb the ladder.

This sounds a bit weird, I know, but bear with me. There have been many training trends during my 14 years of coaching division one athletics, and I’m sure that I will mis-reference some and completely blow others. I remember the different trends such as functional isometrics, isomiometrics, stability training, power factor training, Westside, hatch program, complexes, GPP, insider contrast training, isoballistics, sport only and no training, high intensity training, german volume training, occlusion training all aerobic conditioning, no aerobic conditioning, functional training, and many others.

Here is where the ladder and pendulum insert themselves. Both are trying to get the best results for their clients/athletes. They are both trying to learn new things to gain an edge on their competition. They are both willing to try new things. The difference lies in what they are doing along the way.

RECENT: Meditation for the Coach: Starting the Recovery Process

Those who are of the pendulum group look for the next big thing and want to be their first. They want to be on the cutting edge. They feel like the best thing that’s out there is the thing that they’re not doing. Essentially, all who start out in the profession ride the pendulum waves. Some never get beyond here. They scour the internet, books, journals, DVD's and YouTube. They will find the magic bullet that will give them an edge over their competition.

The other is the ladder. While they may or may not immediately jump on the bandwagon and try something, they are learning about it. They learn all of the what’s, why’s and how’s to this new technique/exercise/programming/etc. They see how this fits into the overall grand scheme of things. They gain a new perspective. Thus, over time they gain a new appreciation of what different things really are and what they do. They like to gain information and store it away. Over the years, these people will gain drawers full of information.

I used to have an old house and have really learned a lot about not only training, but life from having a house that is about 115 years old. One day I had to climb up on a ladder to fix a little corner piece on my house that had fallen off where the roof joins the wall, so that it can protect against light, moisture, etc., from getting in to the house. When I was up there on that ladder, I saw things on my neighbors’ roof like frisbees, an old football, and oddly enough, a single shoe. I also saw how different everything looked from up there and took a moment to enjoy how different the world looked from this perspective. Those who climb the ladder gain a new perspective on things. The more they learn, the higher up the ladder they travel, and the further difference in perspective they give.

A ladder climbing experience of my own: having been in powerlifting since 1995, my programs have always been more powerlifting-based. I saw Olympic lifts, but could always argue against them. They would bring the different arguments of velocity, complex movements, triple extension, and I would always argue how to do this with other different movements. I argued against the value of doing Olympic lifts. When I came across velocity based training, all of a sudden I had a different perspective. I realized that Olympic lifts were speed-strength by nature; they were all above 1.15m/s average velocity. After the studying of this velocity-based training and realizing that speed-strength was developed by moving the bar over 1.1m/s, I had a minor epiphany. The Olympic lifts were simply another means to develop speed-strength. That’s it. It’s another tool in the tool box. Could I develop speed-strength by other means? Yes, but Olympic lifts were good at that and were a good tool for that. Now if I’m trying to develop speed-strength in an athlete, if they have a background in Olympic lifting, I don’t hesitate to implement them immediately.

Now, here is the difference: When someone rides the pendulum, they learn information and they gain knowledge — but it's the ladder that gains wisdom. The ladder sees each passing trend as a tool they can use in the future. The pendulum often just leaves the tool forgotten in the drawer, because they don’t understand it from another perspective. They just know what it’s supposed to do and don’t see how it fits in with overall programming.

For example: If for some reason an individual struggles with transitioning from lighter loads to heavier loads, power factor training can be a good implementation for that person. They can do the partial movements with far heavier weights than they can from partial training. The extra weight causes an extra recruitment of motor units, and getting used to the heavier weights allows the person to be more comfortable with more moderate weights in full ranges of motion. Isomiometric and isoballistic would be good for those players who have to stay down in a stance for an extended period of time and then explode, such as offensive and defensive linemen. Olympic lifts are great for developing explosive or speed-strength. Isometrics at extreme range of motion can help with motor recruitment and are great at strengthening the tendons when placed on full stretch. High intensity training is great for that athlete who is so weak and underdeveloped that they don’t have the strength to get down into a full squat. Some athletes have a hard time balancing, and thus proprioception training would be good. Everything has its place and time, and everything is useful. You just have to know when to use it.

I once had a talk with Jim Wendler, back before he was the tattooed-up Jim "5-3-1" Wendler of today, which changed the way I consumed and processed information. He probably doesn’t remember this, or me for that matter, but we talked at one of the early elitefts.com seminars in St. Louis. Since I had a car and drove both he and Dave Tate around, they were forced to talk to me more. He said something that altered the way I looked at things.

He said, “when you’re writing a program, you should be able to explain exactly what each exercise is, what it does, why you’re doing it, and why you chose the sets and reps you did. If you can’t, your program is worthless. You don’t need to go change everything based off of what you saw in the newest strength and conditioning journal.”

So simple yet so true, and I’ve adhered to that advice over the years. I can explain to you exactly why I do every exercise and program it the way that I do in any of the workouts for any of the sports that I write.

The beauty of what you are, either the pendulum or the ladder, is dependent solely on you. You determine what you do with information. You determine how you process new information. You determine what you implement and how you implement it. You determine if something is completely useless or just used for the wrong task. You determine if you file things away in a drawer and forget about them or if you remember to use them again.

1 Comment