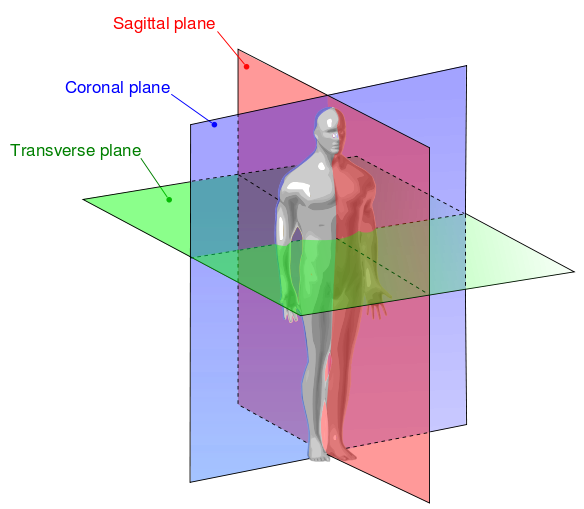

Stability exercises are required to excel in performance and athletic capabilities. As a general rule when training stability, sagittal plane exercises precede frontal plane exercises and frontal plane exercises precede transverse plan exercises. If this order is not chronologically followed, attainment of true transverse stability will be limited. As a result, sagittal and frontal plane weaknesses produce an unstable, weak transverse plane. Inadequate transverse strength and stability tend to appear in the form of acute/chronic pain, compensation, improper form, and dysfunctional movement.

Figure 1: Planes of Human Motion (playthink.wordpress.com)

Here’s a simple assessment that can be applied to attain tri-planar strength and stability.

Assessment

The Single Leg Alternating Bridge (SLAB) is a versatile, under-estimated assessment tool. This exercise will challenge strength and stability in all three planes of motion with various subconscious lessons. Additionally, the added benefit of assessing in an alternating reciprocal fashion will aid in a more functional carryover compared to static assessments. When performing the SLAB as an assessment, subtle to obvious compensations may occur. Local inefficient compensations of the SLAB will help demonstrate the source of global compensations in more dynamic exercises. Such exercises may include squats, deadlifts, and other single-limb movements.

WATCH: Physical Therapy — Anterior Pelvic Tilt Fix with Casey Williams and Dani Overcash

Sagittal plane weakness presents a dropped pelvis when one leg is raised off the floor. Additionally, lumbar extension (false form of stability) will be noticed when there is instability in the sagittal plane. Frontal plane weakness and instability will display itself as a left or right hip shift as one leg is raised. Contrary to the transverse plane, the client or athlete will sustain a neutral pelvis. Furthermore, the inability to hold the transverse plane produces a rotational moment at the pelvis. For example, a left pelvis may remain in position while the right drops. Use the SLAB to conclude which plane of motion has weakness, instability, or a combination of the two that produce compensations.

Fixing Dysfunction

Once the dysfunction is determined, appropriate action can be taken to enhance movement quality and performance capacity. In my opinion, added strength on an unstable foundation is near impossible. Even if this is accomplished, it tends to show as a false sense of stability (compensation) and further promotes dysfunction. Although many approaches can be applied to promote proper movement, utilizing concepts from the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) has personally yielded the most success in my experience. PRI concepts will provide “anchors” (muscles) to ensure proper stability through strength improvements. This is achieved by increasing stability while concomitantly pulling us out of naturally biased patterns.

The art of coaching is presented when a coach fine-tunes adequate levels of desired “anchors.” Providing too much stability risks improper adaptations from the lack of strength needed. Conversely, if there is not enough stability added then the chance of compensation will arise. The coach must provide sufficient stability to properly train, yet be challenging enough without overstimulating the system. In doing so, noticeable improvements can be observed with decreased compensations, increased power, and enhanced strength and stability.

The PRI SLAB is similar to the traditional exercise with the slight utilization difference of a balloon and small ball. Hold onto the balloon, place the ball between your knees, and prevent the ball from dropping. Initiate the exercise in a similar fashion to a traditional bridge by extending the hips towards the ceiling. Once maximal hip extension occurs, seek to maintain this position during the entirety of the exercise.

Prior to lifting one leg, inhale through the nose, pause, and exhale into the balloon, ensuring chest and rib cage depression occurs. This ensures that the abdominals, specifically the obliques, are engaged to provide supplementary support. Next, hold your breath as you slowly move your left knee towards your right. This should engage the left inner thigh and provide an additional “anchor.” Slowly begin to take one leg off the floor while maintaining pelvic position.

The coach must pay close attention to any subtle movements in the pelvis to accurately determine which dysfunctional plane of motion contributes to the instability. Continue by moving to the other leg and repeating the same process, only this time the right knee will push towards the left. Typically, a right inner thigh is not a desired engagement when following PRI. However, we will use it in this scenario to help adequately control the pelvis.

Modification

Force is another factor that can contribute to strength and stability weakness. If the above-mentioned technique still produces less than optimal results, then look to modify. A simple modification that can be added is slowing down the amount of force exposed to the system. To perform this during the PRI SLAB, begin in the same manner. The only variance will be noticed when taking the foot off the ground. Instead of lifting the foot in its entirety, go onto the heel of your foot by lifting your toes off the floor. You can continue to toe tap with each breath or continue the full range of motion as previously demonstrated.

You should feel an increase in body weight and force that has to be sustained, absorbed, and stabilized. When enough stability is produced and the pelvis is maintained in a neutral position, the heel can be slowly be lifted off of the floor and the exercise can be completed as mentioned above.

Final Thoughts

The Single Leg Alternating Bridge is simply effective. It doesn’t take long nor does it require a high level of training, yet it produces quality data to guide coaches with their programming. As a result, observations such as decreased injuries, decreased compensations, increased strength, and increased stability should be noticed. If they’re not, utilize PRI concepts to add more stability to the system. Seek to take away “anchors” as needed and continue to provide the obligatory stimulus to acquire resilient tri-planar movement.

Brian is an up-and-coming strength and conditioning coach. He is the owner of Functional Training Studio in Charlotte, North Carolina. At a young age, Brian has been training clients for over six years and is always looking at ways to improve his technique. He utilizes positional asymmetries that exist within the body to help clients and athletes improve their function and overall performance capacity. Brian has a degree in exercise science and is a certified strength and conditioning coach through the NSCA. Additionally, he plans to continue his education in 2017 in a doctorate of physical therapy program. For additional questions, Brian can be reached at FTStudio130@gmail.com.