A few days ago, a friend showed me a powerlifting article written by some strength coach none of us had ever heard of. As is usually the case, the author had no idea what he was talking about, and had clearly never competed in the sport. Simple principles were incorrectly explained, legitimately great coaches were misquoted, and the whole thing was poorly slapped together with non-relevant pictures and enough clickbait ads to crash Skynet.

Strangely, this piece of shit wasn’t hosted on some fly-by-night blog either. The site in question is one of the biggest names in the fitness publishing industry.

If you’ve been in the fitness industry for a couple of decades like I have, you may be wondering what the hell happened. Fitness articles weren’t this bad when we were starting out, were they?

No, no they weren’t. And the reason has to do with how content is consumed now versus a few years ago. They don’t suck because the authors are incapable of writing good ones — they suck because for a large segment of the industry, there’s literally no way to make a living producing articles that are good.

RECENT: How to Master The Art of Thanksgiving Eating

Before explaining how this works, let's go back a few years.

I started reading fitness publications in the early 90’s. Back then, there were only a handful, with each one affiliated with a major supplement company. In addition to the products they pushed, each publication also had it’s own identity, or "tone”. Some are still around, but others have fallen by the wayside.

Muscle and Fitness — Probably the most generic of all. Walked the line between bodybuilding and fitness. Pushed Weider products.

Flex— Also a Weider publication. Focused on competitive bodybuilding with lots of contest news and gossip. Included fold-out pinups of female bodybuilders that I totally never whacked-off to.

Ironman — The longest running of the bunch at the time, and it felt like it. More focus on “old school” bodybuilding and training. Less focus on which bodybuilders were banging which fitness chicks that month. I don’t remember what their supplement affiliation was (if any) but I’m pretty sure I remember them hawking some old school shake from Steve Reeves, for the dudes out there chasing that perfect bicep-neck-calf ratio.

Muscular Development — Pushed Twinlab. Pretty run of the mill, really. Had a short, ill-advised focus on natural bodybuilding in the late 90’s. Promptly went back to featuring “untested” bodybuilders and regained popularity.

Muscle Media 2000 — The most cutting edge of the bunch for a while. Was the first major publication to acknowledge the role of drugs in bodybuilding. Was also the first magazine to sponsor a nationwide “shape-up” contest to push EAS supplements. Had a short, ill-advised focus on natural bodybuilding in the late 90’s. Promptly disappeared.

Muscleman — Pushed Muscletech supplements. Canadian.

While one can argue that the majority of articles published by these titles were never very good (I mean, just how many biceps routines can you write in a year?) they were far and away better than the crap we have now. Even though the information leaned towards fluff, they were at least well-written from a literary perspective, generally free of typos, and had pictures that actually corresponded to the information provided.

The reason for the relatively high quality was simple: you had to buy them. Not only that, but you had to actually go to a store to drop the three or four bucks to pick them up. And even if you had a subscription, there was still a trip to a mailbox involved, not to mention envelopes and stamps and shit.

On the side of the publisher, magazines are expensive to produce and distribute. This makes publishers extremely selective in who they will allow to produce their content.

Long story short, the content back then was much harder for both the consumer to acquire and publisher to produce than it is now, so if it sucked, no one would go through the trouble of making it, let alone reading it. And because these magazines were being written to push the supplements, the content had better be good or else it would show the products in a negative light.

Consequently, the magazines of the time had much more control over their content than most of today’s websites do. The staffs were generally small, with established editors, photographers and authors being paid well to put out relatively high quality work. While they would take submissions from non-staff contributors, they were always vetted to make sure the quality was adequate.

At this point, I’ve just realized I’ve explained to our younger readers how magazines work. Just like a grandfather explaining his ham radio to bored grandkids.

Anyway, fast forward a few years.

As with most industries, the internet changed everything, but it wasn’t overnight. When traditional periodicals first delved into the world of electronic delivery, they were essentially delivering the same product in a different medium. You would either pay to have the magazine delivered electronically, or a few selected articles from the print version would be made available for download. The quality control, for the most part, was still intact.

Eventually, due to the extraordinarily low cost of internet publishing, the market became flooded with content. Some of it good, most of it crap. It’s no longer a handful of publications competing to have the best product; it's thousands of online publishers competing to have the MOST product, and get it in front of your eyes as efficiently as possible.

Article quality no longer matters for the most part, because readership loyalty is no longer a concern. Most people have no idea where their content is coming from, and will generally just read whatever pops up in their google search first.

I know this, because for a brief while, I used to write this shit myself.

The following describes my own experience as an author of crappy fitness articles. Keep in mind that it’s been 6-7 years since I’ve worked in this capacity, so the industry has presumably changed since my experience with it. But I know for a fact that content produced back then is still being recirculated because I’ve seen my old stuff republished as recently as last year.

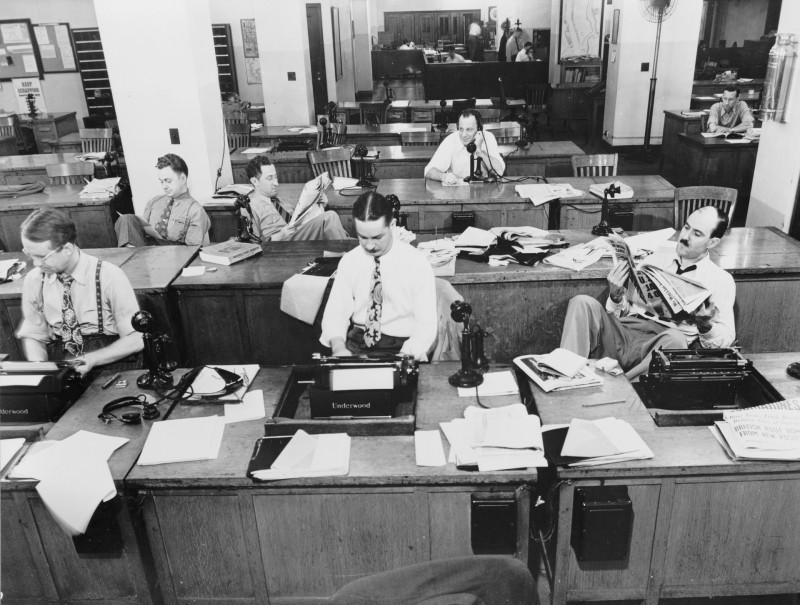

[What we imagine the young Dave Kirschen to look like.}

Most of the content produced for online consumption comes from what the industry refers to as content mills, or farms. And during a brief period of unemployment a few years ago, I found myself writing for one of them in order to support my family. While I can only speak for my experiences at this particular company, they happened to have been the biggest mill at the time, with numerous websites under their umbrella. Sites you’ve absolutely read, especially if you’ve ever started a google search with “how to…”

In my case, I wrote for one of the fitness related sites the content farm owned. Since you actually needed to have some sort of credentials in the industry, I was paid a slightly higher rate per article than the typical author.

That higher rate?

25 dollars per article. And I’ve seen rates as low as three bucks.

You could also agree to get paid on a per-view basis, meaning you’d get paid a tiny amount per view for as long as your article remained on the site. This deal actually had more potential upside in the long run, especially if you were good at writing specifically for SEO (search engine optimization) but I wasn’t in a position to wait and took the immediate payout.

The articles needed to be in the 400-500 word range and include at least two references.

Obviously due to the low payout per article, I needed to write a lot of them. During my brief tenure there, I wrote about 500, generally shitting out five to seven per day. You might be wondering how I even thought up 500 separate subjects to write about, and the answer is that I didn’t. The way it worked was that the site would supply a constantly updating list of titles, which the authors would select, and then write the corresponding article for.

The titles were obviously automatically generated for SEO, because they often wouldn’t even make any sense, like “how to grow biceps with fasting” or some other nonsense. Most of the time, however, it was generic crap like “simple tips for weight loss.”

Once I picked up a suitably bland title, I’d bust out a page of the most boring drivel you’ve ever read, as quickly as possible, attach my references (which were usually a couple of old fitness certification textbooks which I knew would back up whatever common sense statement I had made. I never actually researched any of it because it would have been a waste of time), picked out the least random stock photo I could find from the site’s bank, then sent them off to the editors. If/when the article got accepted, I got my 25 bucks and totally forgot about ever writing it.

Yep, that’s the glamorous life of the average fitness author.

So here’s the really interesting part of the whole thing: I never bothered writing anything but fitness articles, because they had the highest payout, but I could have picked any topic I wanted, and no one would have cared. No one would have even bothered to ask if I actually had any experience with the topic because it was all pretty much automated. Since the editors presumably didn’t have any expertise either, they only edited for grammar, never addressing the actual information provided.

I could have written about home improvement, cooking, auto repair whatever, regardless of whether or I actually had any expertise on it.

And the above point is why so many articles suck so bad. No one really cares if the author knows anything about the topic. The content farm is not interested in experts; they are interested in writers that can crank out pages of keyword-rich content to attract readers to the ads they host. The sites have no actual product to sell, except space to click-bait advertisers. The advertisers don't care if the article is good, because by the time you realize it’s crap, you’ve already seen, and hopefully clicked their ad.

READ: Dave Kirschen's Daddy Hacks

Now, a competent writer should be able to write on just about any topic if given the chance to conduct the necessary research, but remember that with the low payout, it actually works against you to do any real research, because it’s too time consuming. Hence the vast number of articles written by authors with precisely 10 minutes more experience with the topic than you have. By the time you finish the piece, you know exactly as much as they do.

While you did need some sort of credential to be a fitness writer with the company I worked with, I don’t remember it being all that much, and to be honest, I don’t think it would have been all that hard to get away with faking it as long as the articles you submitted when you applied were well-written.

Interestingly, you might think that this type of work attracts only the worst authors. You’d be wrong. Plenty of professional authors were using these sites to earn extra cash between more reputable jobs, usually under pen names (as I did). In fact, it’s actually difficult to earn a living at this type of work unless you are pretty good, because a poor writer will not be able to produce publishable content fast enough for it to be worth the effort.

You might also think that plagiarism would be rampant in this corner of the industry, but it’s actually the opposite. These companies filter every single submission through software that will cross-check it with pretty much everything else published for similarities. If flagged, the content will be further checked by an editor. Plagiarism may be rampant in the fitness industry, but it’s mostly limited to smaller sites and blogs. It’s relatively rare in content mills. This is also the reason the pictures generally suck. Authors are not allowed to submit images due to the high risk of copyright infringement. Authors must select images from a bank of cleared clipart pics, which often have nothing to do with the article.

This is why every nutrition article you read has one of the same five pictures of fruit.

In stark contrast to the classic publishing industry, the biggest weakness to content farms is the lack of accountability. The authors are independent contractors (and I believe most of the editors are as well), so no one really knows or cares who is working for them. I never had so much as an email exchange with anyone who I worked for. The most communication I had with anyone was the notes from random editors attached to articles that needed fixing.

The advertisers don't care because the ads are randomly generated. No one knows which ads are attached to which article. A seller of a product isn’t going to stop using Google AdSense because their ads wound up on a shitty article. As far as they are concerned, the article itself is only a means to get to you looking at their ad in the first place. Their product probably has nothing to do with the content anyway.

So not only is the author of that “six pack abs” article you just shared probably not an expert, but neither is anyone else responsible for it’s existence.

So now that you know how this type of thing generally works, you might be wondering how I feel about my experience there. While I’m not proud of the work I produced at this time, I’m not ashamed either. I did the job I was paid to do well enough to bridge the gap between jobs for a few months. While the articles I produced weren’t great (or even good), nothing I wrote was ever actually wrong or misleading. It was good advice, albeit boring and obvious.

I even became a better writer during this time. Both of my books (“Powerlifting: Year 1” and “The Strength Training Bible”) were produced after my time with the content mill. If I hadn’t already gotten used to producing content at such a high rate, the task of writing a nearly 300-page book would have seemed insurmountable.

And I was a hell of a lot happier earning money this way than simply cashing unemployment checks.

But based on my experience, I can tell you wth pretty good authority that there are a lot of authors out there that while good writers, have no clue what they are writing about, and no one to hold them accountable for it.

So how can you tell if an article is shit or not before you actually invest the time into reading it?

1. The Ads

If the piece is pasted with ads that have nothing to do with the host site, that’s your first clue that the work is subpar. If the article is in list format with each item taking up a page, then it’s total horseshit and will probably crash your phone if you even try to get through it. If you look at the ads attached to this article, by contrast, you’ll notice that they’re all for elitefts.com products/services. The reason for this is that elitefts.com spends a lot of time and money developing content and isn't about to let some other company profit off of what we work so hard to put out. Not only that, but we do not want our message diluted by another company that might not share our values.

2. The Pictures

Quality pictures are expensive to produce, which is why content farms and the more fly-by-night sites don’t use their own. They will either buy generic clip art (in the case of the mills) or simply steal it from companies like us (usually the smaller sites that fly under the radar). A generic, seemingly unrelated image is a big red-flag that the content won’t be much better.

3. The Author

While not knowing an author doesn’t mean they don’t know their stuff, if you are unable to search their name and find out who they are, other than similar looking work (rather than real-world accomplishment), they probably don’t have a substantial level of experience. Or they are writing under a pen name. Neither is good, because they either have no reputation, or they are unwilling to risk what reputation they have over the work you’re about to read.

4. The Site

Unfortunately, though, this no longer makes as big a difference as it should. On one hand, a site you’ve never heard of called wholebunchoffitnesssoundingstuff.com is a dead give away. On the other hand, however, I’ve seen some work from some major fitness publishing names from the old days that are clearly content mill crap. As fast as the industry is changing, it can be hard to determine who’s keeping it real, and who has sold out to the lure of cheap, high-ranking SEO. If the name looks legit, but the ads and pictures tell you otherwise, you know what’s going on.

My advice for getting the most out of online content? Stick with the sites and authors you know and frequent. While you shouldn’t be closed-minded to new, potentially talented authors, pay attention to who they write for. If a highly regarded company isn’t willing to stake their reputation on them, then you probably won’t want to stake your results on them either.

But I actually miss PLUSA. It was ours, and the bare bones presentation was almost charming towards the end. There were also some good monthly columns from guys like Louie Simmons and Ken Leistner. Mike Lambert did the best he could promoting a fringe sport with a small budget and I appreciate the effort he put into it. Unfortunately PLUSA, the real attraction for most of us was the yearly Top 100 list, and once this started being offered online, everyone just lost interest in it.

My first advice would be to just start writing. Like anything else, it's a skill that takes practice. I can't tell you how many people I've met in the industry who are planning to write a book "sometime" and never even put out a single page. It's hard work and it takes more time than most people are willing to invest.

I would also try not to cast too wide a net, and only write about topics you are intimately familiar with (you're a lacrosse guy if I remember, so maybe start with strength training to support that sport). If you try to write about stuff you're either not familiar with, or are not passionate about, it will come through to readers who ARE.

Submit your stuff to resources that specialize in what you are covering, so that your audience is as targeted as possible. You can even start your own blog/site if you think you can put out enough content to support it.

Don't expect to make money at it. Not that you can't at some point, but initially you will be giving away far more than you will sell. The object when you are starting out is to establish yourself as a resource worth reading, so that people care enough to pay for your work down the road.

Take time to develop your voice. This doesn't mean to try and put on fake persona or schtick, it means that you want to get your writing to a point where it is identifiably yours. I've had clients whom I coach in person tell me that my work reads like I talk, so I think i'm on the right track. If I tried to create a character (or just tried to sound like Jim Wendler like everyone else) I wouldn't be able to convey my message as effectively.

Most of all, don't do what EVERYONE else tries to do and get your stuff "out there" right off the bat. If you haven't been writing for this purpose for very long, your articles will most likely suck, and years from now, you might wish you didn't push it so hard. Worry about getting good at it first. You should still publish it where you can, because the feedback will be valuable, but look at tons of hits as a bonus rather than the goal initially.

Start today.

Hope this helps!