Let’s all understand what we’re looking at and use our experience to help others filter through the nonsense.

About 15 years ago, when I really got into strength and conditioning and realized I wanted it to be my career, I got to a point where I was reading 15 different blogs per day. I was starving for information and the more blogs I read, the more prepared I’d be when I worked with the athletes I had. I realized fairly quickly that I couldn’t keep that pace up and a lot of what I ended up reading was redundant, so I cut it down to my top-5.

RELATED: Selecting Appropriate Exercises for Youth Athletes

Today is obviously worse because you can follow far more than 20 coaches and get an astounding amount of information in 15 minutes. This has led to what others call exercise bait: a fancy-looking exercise that looks cool, so you watch and maybe read about it, and now you follow that person’s every move.

Every exercise can be good or bad depending on many different variables. That’s not the point of this article. Whether it’s good or bad doesn’t matter because you may have zero context. It’s just an exercise. The answers to the questions of why, when, who, where were you before, and where are you going are up in the air.

I’ve had this happen to me, so I know how this typically works:

You see something, so you do it yourself, maybe even for a couple of weeks. Then your athletes are next. However, you don’t know common technique flaws or cues to fix those flaws; you just know how some dude on the ‘gram looked and maybe how you felt. Then you see multiple techniques within a small group, and you’re not sure how to fix them. You try to fix them, and some get better and some get worse, and you think, Why did I do that? Was I really prepared to coach this?

In my mind, a big reason everybody squats, deadlifts, bench presses, cleans, lunges, jumps, sprints, and does everything that goes along with this stuff is because our mentors coached thousands of repetitions, taught our mentors who coached thousands of repetitions, and then our mentors taught us what to look for, and we have now coached thousands of repetitions.

We know what to look for; we can spot it in a second, and we know at least half a dozen cues for each technique flaw. And because we’re always coaching these moves, we keep coming up with more cues to reach more athletes in a better way.

My assistant and I have been coaching together for over five years, which is a lot of floor time. Multiple times every week, I walk over to an athlete to give a cue and my assistant yells it out from the other side of the room before I got there. The exact same cue. We’re watching the same thing and seeing the same thing and use a lot of the same cues because they work.

However, I’ll see a movement and wait for an intern to correct it because it looks obvious to me. Our interns have not had the same floor time with us, so they may not be seeing the same thing I do or may not be looking for the same thing. This is where I have to be a better coach, not just to our athletes, but also to our interns because that’s what I, fortunately, got from my mentors.

So how can we avoid common pitfalls with exercise selection and progression?

If we’re starting from the beginning, we look at all resistance training program design variables, straight from the NSCA text.

- Needs Analysis

- Exercise Selection

- Frequency

- Exercise Order

- Training Load and Repetitions

- Volume

- Rest Periods

I remember going through this with each team the first time I had a team to work with. So like many things, we tweak and do what works for us as we gain more experience. Next, we take what the NSCA has given us and made it our own.

READ MORE: Progressions in Exercise Selection Based on Technical Proficiency

Typically this thought process starts at the beginning of the off-season, which means it could be at the start of a new school year. For example’s sake, let’s say that is the case.

- Needs analysis: What is the sport? What have we learned by working with this sport, at this school, with their sports coaches in the past? What are the common injuries associated with this sport? Are there contraindicated exercises for this sport?

- What will be the exercises that I want to track progress with for the upper and lower body? How have we done these in the past? Is there a better option? How will we integrate freshmen into this exercise? Do the freshmen have a training background?

- What is the goal for each of the two potential phases throughout the semester? Is the team in their non-traditional season? If yes, what days and times do they practice? Is the whole team practicing at the same time, or are they doing individual practices? What days are more intense at practice? What days and times actually work for the team to train with strength and conditioning, both in the weight room and for speed/conditioning, if needed? If no, when will they be starting practice, and what is the individual’s schedule?

- What works for their schedule, based on classes as well as our schedule, for days of the week and times of the day?

- What other teams are in the weight room at the same time as this team? Can I use the equipment I want to use (we will not schedule too many athletes per rack, so we can technically fit 40-ish)? If not, is there a way to rearrange the training session/week to make it work better for all parties involved?

- Can I accomplish the training session multiple times per day, in the case of a larger team coming in smaller groups? If not, can I make adjustments to make it as similar as possible? Do I have to start the session somewhere else to leave space in the weight room? Do we have interns during their time to help out in any way?

With all of the ‘gram stuff going around, I now think about the following questions to ask should I ever prescribe a new exercise that I see:

- Can the movement be progressed/regressed? Different implement? Different pattern? Does this exercise fit into a progression track we already have in place, or is it separate?

- Can you progress/regress intensity, speed, range of motion, etc.?

- What am I looking to accomplish? Improved strength on main movements? Power? Mobility?

- What have I done in the past to accomplish this? Is there something that I can coach better that may work just as well?

- Can I explain why we are doing it to athletes and coaches? If not, I’m full of shit.

- Is the movement backed up by research? As I mentioned before, we do the movements we were taught and learned from others who have done them for decades. Research can be formal (published) or informal (anecdotal). Both types carry weight.

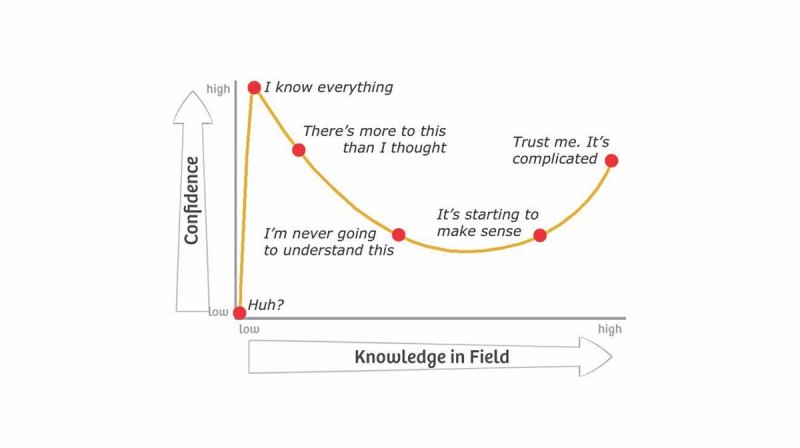

Dunning-Krueger Effect

The last piece to this rant-ish article is the Dunning-Krueger Effect. The faster we can get coaches past the “I-know-everything” phase, the better we will be as a profession. However, everybody has to get there on their own. Also, the “I-know-everything” coaches don’t know they’re at that level, so when they post some BS, they really do think they are at the far right end of that table above.

There’s nothing we can do about that except keep spreading the truth, keep sharing the stuff on sites like this, keep liking the good ones in the field, and stop following, liking, and sharing the BS. This is publicity, and there’s no such thing as a good share or a bad share; a share is a share, and a follow is a follow. Drive ‘em out by ignoring the garbage.

Bobby Fisk is the head strength and conditioning coach at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. He can be reached at fisk@njit.edu.