How much should I be exercising? It is a great question, and yet it is one not easily answered. Today, I want to give you a simple formula to help answer this question. Before we get into the more nuanced points, I want to make one overarching theme clear: no one training protocol is perfect for everybody.

If you’re hoping to find an all-encompassing regimen, one that will get you stronger, leaner, and faster all at once, you’ll be looking for a long time. That’s not to say you can’t excel in multiple facets of fitness concurrently, but you’d be better served zoning in on one goal at a time.

RELATED: How Many Exercise Variations Do You Need?

I want to first define three pillars of what we’ll be calling “training economy.” Training economy refers to the way we will choose to spend our exercise capacity. In simple terms, if you think about your ability to exercise as a bank account, we want to consider what the smartest way of spending our training dollars would be to attain whatever goal we’ve set forth. Keeping with the metaphor of a bank account, I want you to consider how much money you can allot for training.

Say you’re a 20-something college student with no kids and no job. It’s safe to say you can afford more exercise than a 32-year-old mother of two working a full 40 hours per week. This isn’t to say the young students training will be better than our mother of two’s training, just that it will be different. Now that you have a grasp of your exercise capacity, we’ll move forward with the three pillars: training volume, training intensity, and training frequency.

Firstly, training volume defines how much exercise we perform in a given training session (i.e., reps x sets x load x sessions per week) would give us our weekly training volume. Typically, we would use this formula to gauge the total volume of our compound movements, such as the squat, deadlift, and bench press. As volume increases, we typically see a drop in both training intensity and frequency. Of course, you can always increase training volume while also aiming to achieve higher levels of frequency and intensity, but that’d be ill-advised for reasons I’ll explain later.

Our second expense related to exercise capacity is training intensity. Intensity is the level of effort put forth in a given set of any exercise. Think about it this way: Lifting a 300-pound barbell when your max is 330 pounds is significantly more intense than lifting a 200-pound bar. Likewise, a full-speed 100m dash can be considered more intense than a three-mile jog. Performing exercise at higher intensities is one of the greatest ways to enhance your ability to strain harder; unfortunately, it’s also incredibly taxing on the body, causing intensity and frequency to have an inverse relationship.

Our final expense, the number of times you perform an exercise in a given week or month, is termed training frequency. Unlike the other two pillars of training economy, training frequency tends to be dictated more by outside life demands. Someone who only has time enough to train three days per week has obviously different degrees of training frequency than a two-sport high school athlete with daily practices.

So now we have a well-defined sense of our training capacity (the bank account) and three pillars of training economy (the bills). With this information, we can now identify a path to any goal we may have.

We have to look at our schedule and get an idea of what kind of training frequency we can afford. Most people can determine their training frequency by looking at their lifestyle demands. These demands include all work, errands, and other weekly obligations. Your training frequency is going to be determined by what you can fit into the time between all of those demands.

This may look like a five-day routine Monday through Friday, or maybe you find it easier to get in three non-consecutive sessions (i.e., Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday). Whatever your workout schedule allows, I assure you, any training goal is attainable. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to continue defining my current training regimen.

Currently, I’m following a three day per week training schedule of Monday, Wednesday and Friday workouts. In my opinion, this is a relatively moderate amount of training frequency and, as stated before, training frequency has an inverse relationship with training intensity.

READ MORE: What I've Learned From the Mistakes I've Made as A Trainer

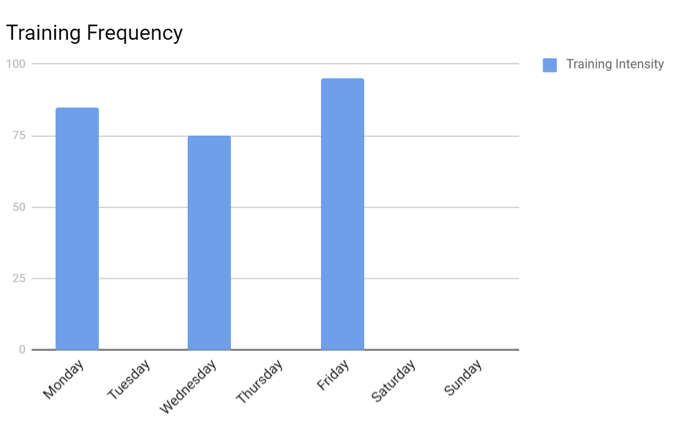

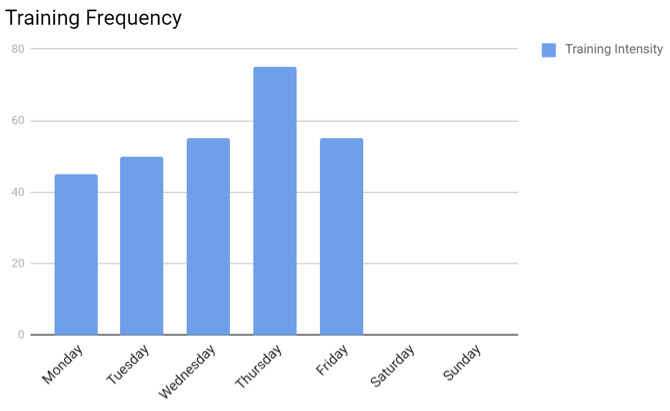

Due to this fact, training intensity is fairly high for me right now. Most of my workouts are performed at intensities where I’m working near or above 80 percent of my maximum effort. If I were to switch to a more frequent training schedule, such as Monday through Friday, I would simply decrease the intensity of any given training session. The charts below are a simple representation of the relationship between intensity and frequency.

As you’ll notice in Example A, the training frequency is down to three sessions per week due to the lesser training sessions in which the intensity of each session is at or above 75 percent. The opposite holds true for Example B wherein the training sessions per week are up to five, but the intensity of each session is at or below 75 percent with a majority of training being done below 65 percent.

Example A:

Example B:

Now earlier, I had stated that aiming to improve all aspects of fitness simultaneously could be an ill-fated goal. This is not to be confused with an impossibility, though. In fact, professional athletes more often than not aim to increase all aspects of athletic performance at once: power output, speed, maximal strength, etc.

Of course, professional athletes live far different lives than the general population or exercise enthusiast. Herein lies the dilemma: because our general population lifter cannot afford to decrease demands of life as LeBron James can, they will not be able to recover from the intensity and frequency which it takes to optimize all tenets of fitness concurrently. For this reason, coaches, on the whole, will more commonly guide a trainee toward one or two specific goals during a given training period. This might look like prioritizing the 1RM deadlift for a four-month cycle or perhaps increasing miles per week leading up to an endurance event. Yes, these two goals can be simultaneously trained, but the end result would be attained at a slower rate of progress than if we were to commit fully to a singular goal then transition to the next.

My hope for any of you lifters, young or old, novice or elite, would be that you can take a more educated approach to your next training program. Although some of the information presented can be complex, I encourage you to begin tracking the three pillars of training economy in your weightlifting career. Even if it helps you only marginally increase your fitness from year to year, you’ll be greatly rewarded when you look back 10, 20, or even 30 years on from now.