So you have decided to open a gym. You have done some market research and you have chosen an area of the city where you have higher chances of succeeding as a business. You may or may not, however, have considered in detail the service you will offer the local community. “Fitness” is no longer enough of a concept for decision-making, and hasn’t been so for some time. The gym market is highly segmented and responds to different needs from consumers. Some middle to higher end chain gyms try to offer a little bit of everything, with a highly sophisticated partitioning of the spatial environment for optimal level of private space preservation. Others, like Planet Fitness, offer the cheapest fitness alternative and a high level of private space preservation.

RECENT: Supermen: Cross-Athleticism, Who These Guys Are, and How They Ended Up There

The first thing that stands out looking at the various strategies adopted by gym owners is that the commercial gym is a complex social environment where different goals and projects are pursued and where there will necessarily be some social interaction. Whether harmful or positive, ghetto-like and exclusive or pasteurized and inclusive, it depends on hard choices made by the owner.

In this article, I invite you to consider simple choices concerning space arrangement, staff training, and member customer service through the following items:

- Who does your gym serve?

- How is space socially segmented?

- How does the gym environment foster member goals and projects?

- How can you make a difference?

Here you will be introduced to some tools from the social sciences that have been shown to be useful to answer these questions.

Tips for future business owners and a guide for equipment purchase have already been published here:

- How to Know If You Should Open a Gym

- Gym Business: What I Wish I Knew When I Started

- Three Phases of Purchasing Gym Equipment for New Gym Owners

Who does your gym serve?

The answer to this question only partly depends on you (the gym owner). Consider, for example, a middle-class area in one of DC’s satellite cities where you find a CrossFit box, a Onelife Fitness club, a rec center, and a few specialty facilities (a Pilates studio, a yoga club, a dance studio). People will gravitate towards the facility that best serves them. Competitively driven and professionally successful adults might find that the CrossFit box is for them, while the less interactive, equally successful (or not) ones will choose Onelife Fitness, where they will have a little of everything; they may reserve one day to isolate themselves and do laps at the pool or join a class in the “CrossFit-like” space if they are feeling more sociable. The busier or more financially constrained people will choose the rec center. The specialty facilities are predominantly chosen by people who avoid the “gym culture” for one reason or another.

Your competitors practice prices ranging from $50 to $130 per month.

But you might have identified social segments whose needs are unaddressed or only partially addressed in the area. Sometimes that happens accidentally and not as a result of a detailed market research. Non-chain gyms have a way of shaping themselves to the community. Suppose yours is “discovered” by a group of older people, or a community of mountain climbers, or a weight loss club, or local high school wrestling kids. You may offer folders with information about weight loss from reliable organizations and you may organize weekend seminars about the issues these groups are interested in. The challenge is to understand your demographic, their characteristics, their expectations, and also their frustrations.

Let us look at a different landscape. You decided to open a gym at a degraded area in the city, but one that is still densely populated and has a stable demographic profile. There is a high concentration of Hispanic immigrants (from first to third generation), elderly people, and an important presence of veterans with poor health and transients or quasi-transients. The fitness market in this area is comprised of one Planet Fitness club and a few small barbell clubs, two of them gang-associated. You visit all facilities and observe that:

- Planet Fitness is doing great, practicing prices from $10 to $20 per month.

- The small barbell clubs have unsafe and poor-quality equipment, with bad maintenance.

- At least 50% of the people are speaking Spanish in all facilities.

First and obvious observation: you cannot compete with Planet Fitness. You may complement it. The second thing you observe is that those who chose Planet Fitness do not overlap with those in the barbell gyms. The obvious must be stated here: they feel intimidated and they have several reasons for that. The environment at the barbell clubs becomes openly hostile at certain hours of the day, very loud, mostly occupied by males expanding their private space as much as possible with confrontational body language, loud music, loud speech, and objects scattered around.

With some creativity, you may be able to offer quality free-weight equipment at your gym. Most importantly, your main asset will be the skills or people who can reach out to potential members with special needs. You must either speak Spanish or you must hire a Spanish-speaking trainer to help you with everything, considering it will be a small, low-cost, facility. The incidence of obesity among the Hispanic community, especially women, is an important public health issue. It may be a good idea to partner with the Hispanic Health organizations in the area and offer to speak about food habit transition: obesity among immigrants is associated with the transition from the home country’s traditional food to American industrialized cheap food items. You gain their trust, you gain their membership.

You may also consider offering as many free memberships to veterans as you can (through the organization Lift for the 22) and reaching out to veterans organizations. If you are able to offer a safe lifting environment and you show willingness to assist this population, again, you gain their trust and their business. The approach summarized in the expression “my dream, my gym” is only partly true or practical (but it may be your choice). Commercial gyms are a service. Therefore, they are about a customer base. Your choices will be best if informed by an understanding of their sub-cultures.

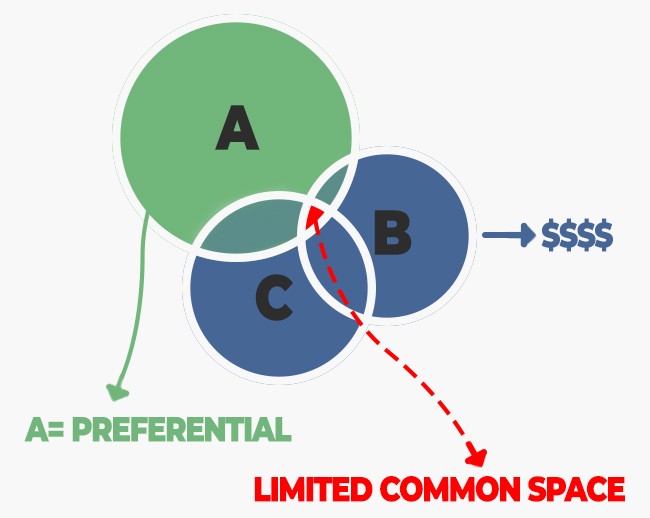

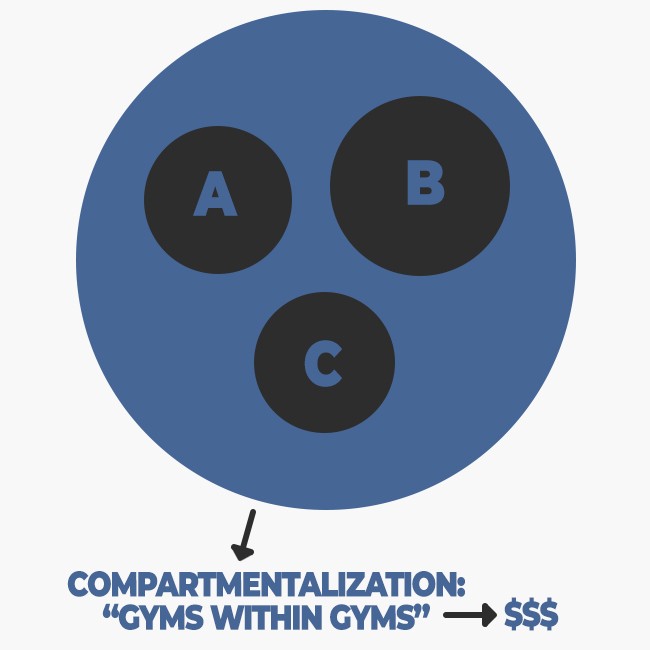

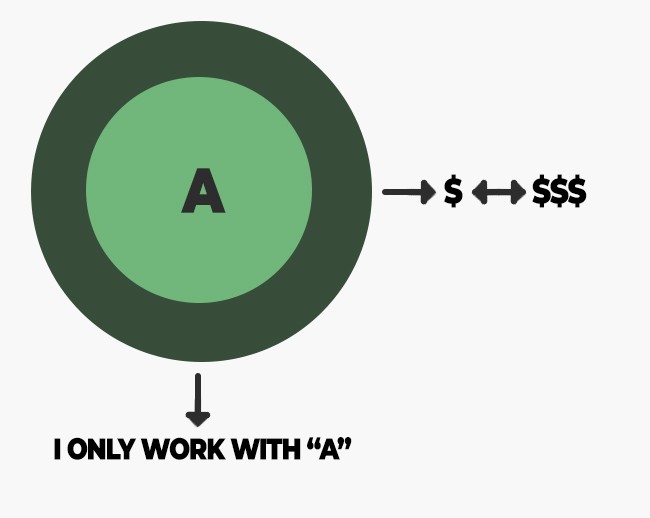

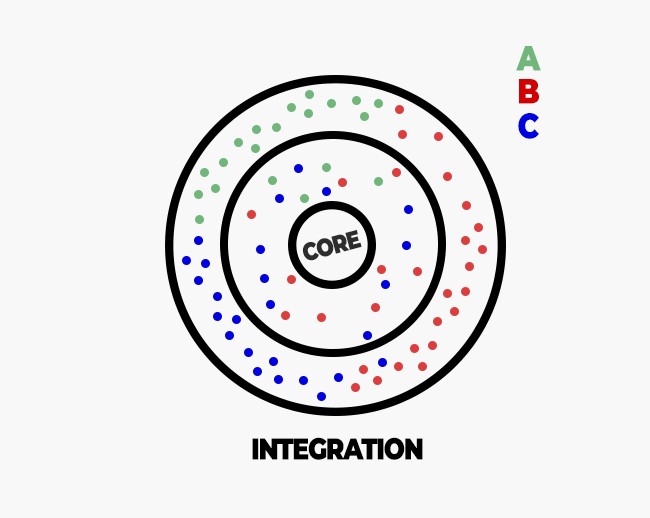

Below is a set of (ugly) images representing the options you have concerning different sub-cultures in your local market. From a highly exclusive (typical strength gyms), to relatively exclusive (CrossFit boxes; see Crockett & Butryn 2017), through different integration models, they all involve some type of understanding of the local sub-cultures. You might as well benefit from a more technical approach.

How is space socially segmented?

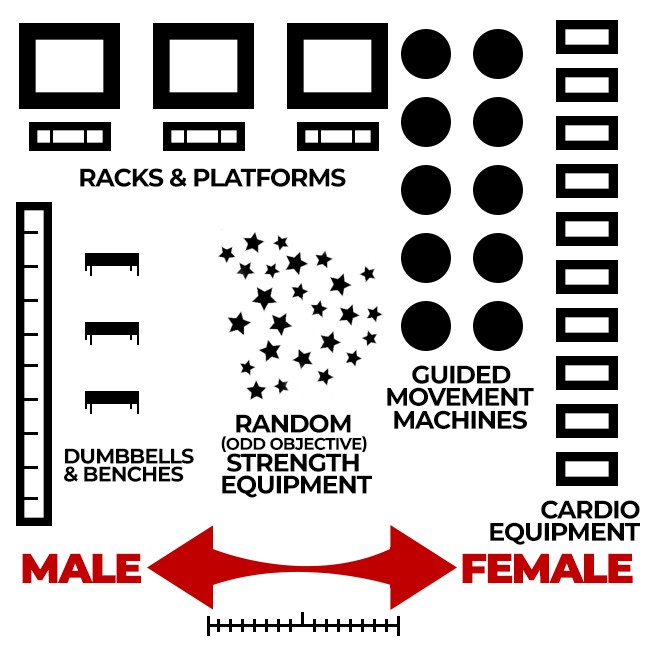

The picture below represents a generic commercial gym. The gender or sex spatial self-organization is not exactly a new idea; whether women are excluded or self-exclude from certain activity-specific areas of the gym is inconclusive, but the fact that females tend to gravitate to certain spaces and males to others is not disputed. CrossFit boxes seem to be an exception (Crockett & Butryn 2017), but they tend to be exclusive in other ways, being only hospitable to those that adhere to the highly competitive weightlifting and gymnastics-based approach to training.

Except for CrossFit boxes or sport-specific gyms or studios, gyms tend to segregate members according to gender, age, skill mastery, and even performance level (“only the strong”, and their girlfriends, of course). For studies on gym space segregation, see Newhall (2013), Andrews and collaborators (2005), and Andreasson (2014).

This type of segregation is not ideal. Speaking on strictly exercise science terms, it is actually bad. We are finally over the urban legends according to which “cardio drains your strength”, “strength makes you muscle-bound”, “guided movement machines optimize strength and are safer” or “guided movement machines are from hell”. Ideally, everybody could benefit from most of the equipment a gym has to offer and most of the movements that can be executed with them. Obviously, it is less probable that a historically sedentary 60-year-old businessman will want or succeed in mastering the snatch or the clean and jerk. But if he doesn’t have any serious injury and really wants it, why not? I’ve seen it happen. It is just a question of adjusting loads.

What can you do to foster integration if spatial segregation is deeply ingrained in the local culture? First, you need to ask yourself if you want or believe integration is positive to your members. I would say it usually is. The first steps are to eliminate specific cultural makers that are employed precisely to keep the “other” away: culture-specific and loud environment music, strong colors, graffiti, etc. You don’t want any of that. You want to seek the minimal cultural denominator. Anything that excludes the other is working against your strategy. If you need to, get help from a professional to choose wall, floor, and equipment colors.

Another strategy that my team employed and was promising was the “gym cicerone." Either you, your partner or employee, or even an intern are responsible for deliberately integrating self-segregating groups. He or she will take the elderly ladies into the dumbbell or power rack areas, work with them at their will at the safest possible zone, and make them feel comfortable there. If they incorporate that space into their routines or not will be their option, but the cicerone is there to make sure everyone is comfortable everywhere and knows what the equipment is for. That is also great to prevent equipment abuse. People don’t destroy Olympic bars out of cruelty, but because they don’t know any better.

A powerful strategy is to enroll well-trained members as “hosts” to their environment (with whatever incentive you can come up with). Having a big bodybuilder offer to show a skinny adolescent or older lady around at the dumbbell or platform area is something that more often than not results in positive outcomes, friendship, or even mentorship. Similar strategies were suggested at the IHRSA report under the “onboarding program” (Brentdarden 2018). The emphasis there is on member’s self-efficacy and goals, rather than the cicerone program I suggest, which focuses on integration.

At the end of the day, understanding the cultural dynamics of your gym makes integration, partial integration, or deliberate partial segregation your choice, not a fatality.

How does the gym environment foster member goals and projects?

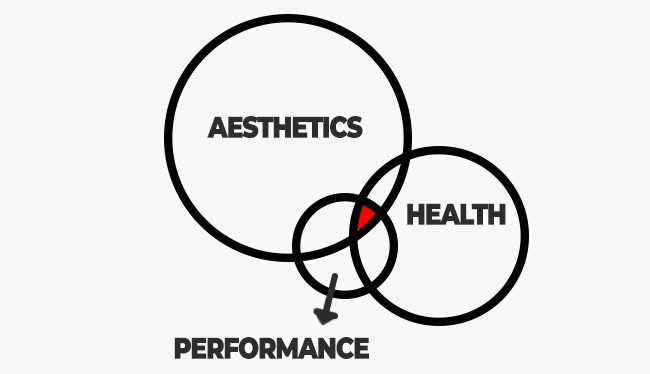

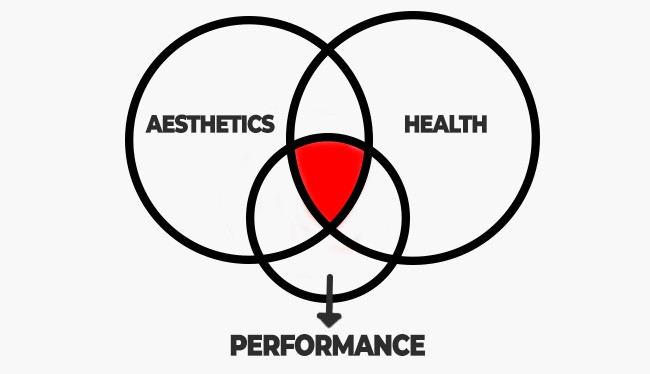

Specific goals have infinite variation, but usually they can be grouped into three major categories: health, aesthetics, and performance. How much or how little they overlap depends on several things, but chiefly on the gym culture that you, a gym owner, establish. The more you promote education and integration among your members, the more overlap you will observe. Ideally, the higher the overlap, the higher the satisfaction.

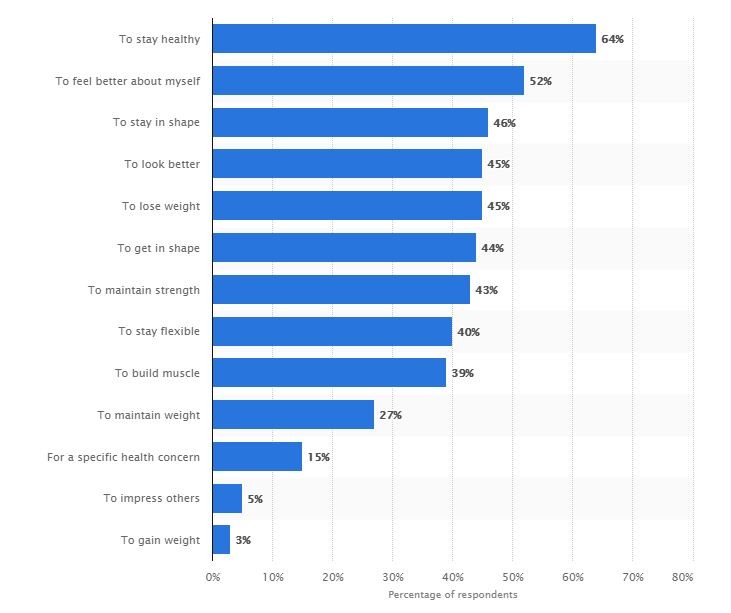

Statista — Which of the following are personal goals for using the health club you currently belong to?* from https://www.statista.com/statistics/246960/personal-goals-for-using-a-health-club/ May 2018

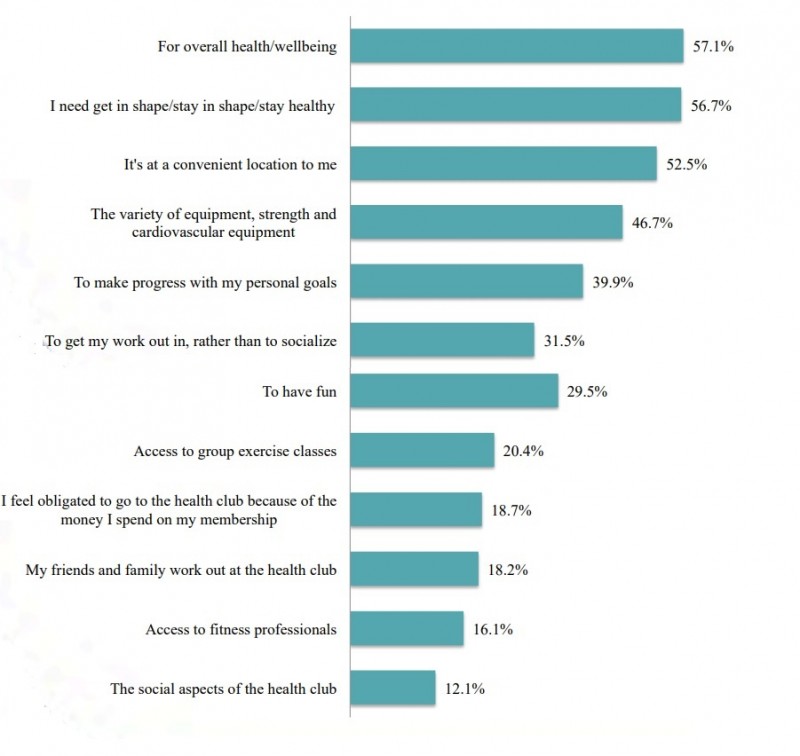

What Keeps You Coming Back to the Health Club You Currently Belong To? - IHRSA 2013 – ihrsa.org/research

Performance is a minor component for most commercial gyms, especially because it is largely understood as a competitive or sports goal. If performance is re-phrased as exercise skill mastery, which is a great goal both for program effectiveness and for safety, we have more overlap. Goal achievement is directly related to self-efficacy, but self-efficacy doesn’t happen in a void. It happens in a certain space and time and a specific social setting. Studies show that social belongingness (the basis for integration) and other social indicators are determinants (Whiteman-Sandland et al 2016, Teychenne 2015).

Again, the chances of increasing members’ success concerning their goal or project are directly related to their on-ground gym experience, how comfortable and welcome they feel in the environment, and on your level of control over the integration and segregation dynamic.

How can you make a difference?

The key to making a difference is deciding for whom you want to make a difference. Perhaps this should be the first question to ask. Maybe you already have asked this question and you are opening the gym because you are convinced that you can make a difference. However, maybe you didn’t think it through and you are just going with the flow, hoping that building your dream gym will make a difference.

That’s not bad, and you might be surprised at how dynamic the gym-building process may be if you have started only with your blood and guts and haven’t put so much thought into analyzing the social setting where your gym sits. Blood and guts are great, because they make you an open channel for empathizing with other people’s needs — or not. Again, it’s your choice. You may have decided that you simply want to alienate all those who are not “hardcore”, “beast mode”, “no pain, no gain” “gangsta” types. All you have to do is display signs that only these people are welcome: lots of black paint, aggressive graffiti, very loud music, and invite the experienced strength athletes for the opening month. There might be a large enough community of powerlifters and strongmen that your gym will serve. You can make a difference.

Or you may decide that you are ready to offer “strength for the people”, to quote Pavel Tsatsouline (although I’m not sure that’s what he meant). It will be much harder, but that might be your calling.

Your choice.

References

- Andreasson, Jesper. "‘Shut up and squat!’Learning body knowledge within the gym." Ethnography and Education 9, no. 1 (2014): 1-15. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17457823.2013.828473

- Andrews, Gavin J., Mark I. Sudwell, and Andrew C. Sparkes. "Towards a geography of fitness: an ethnographic case study of the gym in British bodybuilding culture." Social science & medicine 60, no. 4 (2005): 877-891. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15571903

- Club Industry Member Engagement & Retention Show - Brentdarden.com - retrieved on May 2018 at http://www.clubindustryshow.com/clb17/Custom/Handout/Speaker0_Session1018929_1.pdf

- Crockett, Matt, and Ted Butryn. "Chasing Rx: A Spatial Ethnography of the CrossFit Gym." Sociology of Sport Journal (2017): 1-34. https://journals.humankinetics.com/doi/abs/10.1123/ssj.2017-0115

- Newhall, Kristine E.. "Is this working out?: a spatial analysis of women in the gym." PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2013. http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/2594.

- Teychenne, Megan, Kylie Ball, Jo Salmon, Robin M. Daly, David A. Crawford, Parneet Sethi, Michelle Jorna, and David W. Dunstan. "Adoption and maintenance of gym-based strength training in the community setting in adults with excess weight or type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial." International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12, no. 1 (2015): 105. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-015-0266-5

- Whiteman-Sandland, Jessica, Jemma Hawkins, and Debbie Clayton. "The role of social capital and community belongingness for exercise adherence: An exploratory study of the CrossFit gym model." Journal of health psychology (2016): 1359105316664132. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1359105316664132

1 Comment