Something that NEVER made sense to me in the old linear model of periodization for sports was when coaches were peaking their athletes for their power phase and how the load constantly increased, and subsequently, bar speed decreased.

One of the main components performance coaches brag about when they describe their power program is how they are increasing the speed of the lift in order to get a greater power output. How many times have you heard something like this: “Power is the ability to display your strength with speed”?

RECENT: Explosive Strength and Plyometric Options for Upper Body: How and When to Implement Them

If speed is what we’re going after, then why do the weights on both our heavy and light days continue to climb, and bar speed continues to fall? This is the complete opposite of training from GPP to SPP, especially if you are involved in a speed-dominant sport. How many sports are not speed-dominant? Not to mention the fact that you are getting deeper and deeper into the competitive season and are continuing to put more tonnage on your athletes when the fatigue of the season is going to be at the highest. You are burning the candle at both ends.

Let’s break this down a little and see why we shouldn’t be using this archaic model to get our athletes ready for their most important time of year.

Train What You Say You’re Training

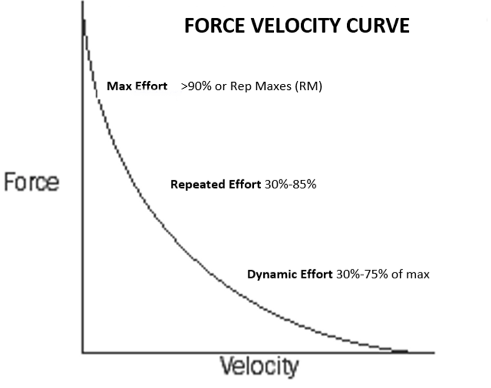

Here we are again with this GD graph. I hate graphs, but someone told me most people are visual learners. The issue we have with many programs when they are entering the power phase is the majority of their compound lifts are creeping up the slope towards the 90 percent range. As the graph shows, the velocity of the bar is continually slowing down as the loads head in this direction. One could argue that they are using Olympic lifts, and the lifts are fast, even though the load’s increasing, but the issue is you are still not directing your training to the direction of your ultimate goal: Speed. The issue of beating the athletes into the ground comes back into play also. At the time of year when accumulated fatigue will be highest, you continue to increase tonnage on them. This makes no sense.

The Guy Who Does “Westside” is Telling Me Not to Lift Heavy?

WHOA! Slow down a little bit here. I’m not saying abandon all heavy lifting and only do speed work. What I’m saying is at about four to six weeks out from your big competition or playoff time, you should take a little priority off of maximal strength and put it on speed. If you are running a conjugate model at four weeks out, start cutting the max effort work a little early. They don’t need to do a true max effort lift. You can cut them when their form starts to break, at an 8/10 RPE, or cut them off at a certain percentage of a previously determined 1RM. This is NOT true max effort work, but it will be in the max effort lane of your program.

All three of these options will give the athlete enough stimuli to maintain and even progress their strength for the last few weeks of the season. Remember, our main priority right now is speed and being able to stay alive while chasing championships. If you are running a linear model, I would suggest using Prilipin’s chart and starting to slowly decrease bar weight and increasing bar speed on your heavy days.

During the week before your big competition, it would be a good idea to be somewhere down around 70 percent on squats and moving the bar as fast as you can on your heavy day. This way you are directing your training toward your goal — not going away from it. On your light day, the percentage could be even lower. 50 percent on your light day with max bar velocity would be a good guideline to use.

If You Don’t Have Max Effort/Heavy Speed Days In-Season

This is many times the case with team sports. Running a circa max phase with this training schedule has always worked very well for us (here come the powerlifters with their torches and pitchforks). Here is an example of how to set that up:

- 3 weeks out: Work up to a max attempt (DO NOT MISS) with almost double the band tension the athlete used during the off-season.

- 2 weeks out: Use the same band tension and do 4-5 sets of 2 with 40% of the previous week’s max.

- 1 week (or early in the week of competition): 3-4 sets of 2 with 30% of Week 1’s max.

The point of this is to transition from a HUGE neurological heavy stimulus to speed. This only covers the squat portion, but hopefully, you get the idea. There is a much more detailed set-up of a circa max phase here.

If I were running a linear model, I would — shit, let’s be honest. I wouldn’t do that. BUT if you were to do it in the linear model, you could get the athletes up to 85 to 90 percent at about six weeks out, then start tapering them down in weight and increasing bar speed as the weeks got closer to competition.

This way, you would be directing your training in the direction of the sporting needs and taking overall tonnage off the athlete so they can execute the most important task: their sport!