Look at this guy.

He must have built that using weights, right? I mean, he must have! He’s jacked as a horse. Sorry to burst your bubble, but that’s Raj Bhavsar, an elite gymnast who has an amazing physique, built almost purely from bodyweight training (he does lift weights, but only for static holds). Surprised? I was too, two years ago when I thought bodyweight training was for people who just like to do party tricks.

Boy, was I wrong.

Why Bodyweight Training Is Effective

We know that to build muscle we need a certain stimulus (e.g. lifting weights), proper materials (calories and protein), and a good environment (good sleep and low stress). That stimulus has to be something that disrupts the muscle enough so that it has to adapt (grow stronger and bigger). A regular dose of resistance training is needed to consistently build muscle. Why couldn’t that resistance come from our own bodyweight?

Resistance is resistance, no matter from which source it comes. When you do a push-up, your body doesn’t just go, "What, he's doing a push-up? Nah, I ain't growing" and then when you bench press alternate to, "Oh yeah, we've got some real shit right there. Gotta get growing!" It only knows tension, and tension can be easily applied using your own bodyweight. Lots of bodybuilders shun bodyweight training because of its easiness.

Let me ask you this: Do you think you can do this?

Photo credit: ayphoto © 123rf.com

Or this?

Photo credit: Aleksey Mnogosmyslov © 123rf.com

I don’t think so.

The problem with the mainstream perception of calisthenics is that people think your only tools are pull-ups, dips, push-ups and the basic exercises. Wrong. There are hundreds—literally hundreds—of high-level, very difficult exercises that take years to master, but when mastered lead to an amazing physique.

“Well, what about progressive overload? I can’t progress on calisthenics as well as with lifting weights.”

You’re right on that one, bro. I’m not propagating that bodyweight training is superior to weightlifting. In fact, if I were to choose one or the other, I’d choose lifting (I do both, if you’re wondering) But, what I am propagating is that people who don’t like lifting weights don’t have to restrict themselves to it. People who are like me love weightlifting, but when you describe it accurately, you see why a lot of people find it boring and dull. You lift a weight, wait a few minutes, lift it again, and then repeat for about an hour. Bodyweight exercises, on the other hand, are much more fun to do. Regarding progression, the main method is progressing to more difficult variations of the given exercise. For instance, here’s a progression chart for the humble push up:

- Knees on the Ground Push-Up

- Incline Push-Up

- Knees-Elevated Push-Up

- Regular Push-Up

- Single-Leg Push-Up

- Decline Push-Up

- Assisted One-Hand Push-Up

- One-Hand Push-Up

If you can’t progress to the next progression then you progress by doing more reps; if you’re doing push-ups for six reps, but can’t do single-leg push-ups for four reps, build up your regular push-ups for 10 reps. Additionally, you can use plain old weights. Yes, I know that then doesn’t make it a 100% bodyweight exercise, but I couldn’t call the article, “The Bodyweight Training with Some Not 100% Bodyweight Exercises Bible”, could I? If you don’t want to invest in weights or resistance bands, you can use common objects. Fill up a backpack with some random shit and you can use it for any exercise (it can even allow you to do extra exercises like biceps curls and lateral raises).

The Problem of Isolation

“What about my biceps? I can’t isolate them using bodyweight training.”

Another good point. Isolating certain muscle groups is very hard to do with bodyweight training. That doesn’t mean you can’t build them, though. Biceps are heavily involved in pulling exercises like pull-ups and rows, and there are certain exercises like the bodyweight curl to work them. Other muscle groups like side and rear delts will take longer to build with calisthenics, but they can still be built.

RELATED: 8 Beginner Bodyweight Exercises You Suck At (But Will Make You A Better Lifter)

So, let’s look at the advantages. The cost of bodyweight training is minimal. You can train movements like push-ups and squats anywhere, pull-ups can be done on staircases or any suitable surface, and dips can be done between two chairs or kitchen counters. I highly encourage you to invest in some rings, though. Rings are very important for further progression and building your arms. They’re relatively inexpensive, often found for under $30, and will last you forever. Or you could make them yourself. If you want to stay fit when traveling, calisthenics are ideal. Gym hotels are notoriously low quality, and sometimes you won’t even find one. Calisthenics can be done anywhere, with no equipment required (though I do recommend bringing some resistance bands along). And it looks cool. (What? It does.)

And the disadvantages: Isolating certain muscle groups is harder, but they can still be built. Progression can halt for a long time, which can lead to demotivation.

The Diet

Before any mention of training, we need to look at the most important bit: your diet. Overweight individuals will have a hard time getting into calisthenics due to their bodyweight and lack of strength. This is why it’s crucial you diet down to a low body fat percentage. That doesn’t mean you need to postpone your training and stick to cardio; it just means you need to go on a diet while you’re training. Here's a short how-to guide here:

- Be in a caloric deficit. That means consistently eat fewer calories than you burn.

- Eat a high protein diet (0.6 to one gram per pounds of body weight).

- Protein is crucial for muscle growth, boosts your metabolism, and makes you more satiated.

- Figure out your optimal carb and fat intake.

- Some people feel amazing when eating carbs. Some feel like crap when eating carbs. Figure out which person you are and adjust your carb intake based on that.

- Eat your goddamn vegetables. Seriously.

- When you’re lean enough, I’d suggest learning how to recomp.

The Importance of Sleep

Okay, I know you want to get to the training bit, and I know I sound like your mum, but I’ve got to emphasize how important sleep is. Sleep is the time when muscles recover and fat is being burned off. Cutting your sleep can leave you with 55% less muscle and 60% less fat burned.

So, do everything you can to optimize your sleep schedule: Avoid staring at electronic screens one hour before sleeping, or use a program like f.lux and Twilight. Establish a relaxing pre-sleep routine (e.g. meditating, reading a book, etc.). Avoid stimulants like caffeine in the hours leading up to sleep.

How to Make a Bodyweight Training Routine

A guide on making your own routine is always going to be tough to write. There are so many individual factors that you need to take care of to build an optimal routine.

First is your training age. How long have you been training? This includes weightlifting and bodyweight training. Beginners should stick to the basic exercises, focusing on perfecting their form. This the time where neural patterns are ingrained. If you consistently do exercises with a bad form, it will stick and set you up for injuries when you move on to more advanced exercises. Beginners to bodyweight training but not to weightlifting should still stick with the basic exercises (since they need to learn them) but with a higher volume. More advanced trainees need to increase their volume and of course progress to more difficult variations.

How much volume? For beginners, I’d say nine weekly sets per muscle group. This is enough to cause a stimulus but low enough to not hamper recovery. As you advance, you’ll stop responding to these low amounts of volume. Your strength and muscle growth will stagnate, at which point you need to increase the volume for the given muscle group. Add two sets and see how you respond. Wait one to two weeks, and if you’re still not progressing, add two more sets. Repeat until death.

What’s the best frequency? The general consensus is that higher frequencies (two to three times per week) are better than once per week. Beginners should start with three times per week, since it would lead to the fastest strength gains (the more you work a movement, the better you become at it) and they’re not causing a lot of stress, thus they can recover quickly. As you progress, however, you may find you work better with lower or higher frequencies. The strength of the connective tissues varies from person to person. When you move on to more difficult exercises that impose more stress on your body, you may find a higher frequency is not suitable. If that’s the case, stick to once to twice per week, depending on the muscle group. Conversely, some have amazing connective tissues and can handle an even higher frequency (four to six times per week). You need to look at markers of recovery, such as:

- Sleep — How well are you sleeping? Do you have trouble falling asleep?

- Strength — Are you losing or just not gaining any strength?

- Motivation — How is your general energy level?

- Pain — Are you experiencing any odd aches and pains?

If multiple markers are negative, you’re definitely under-recovered and need to either lower frequency or lower volume.

Constructing the Routine

Beginners

Since beginners are very weak, they won’t cause a lot of stress on the muscle, and as such can recover quite easily. An optimal frequency would be three times per week, but you can use different ones based on your preferences. In terms of the rep range used, I like to stick to four to six reps for beginners. You can use any rep range to cause muscle growth, but for optimal strength lower rep ranges are preferred. Hence, I like to milk the strength gains out of the beginner as much as possible. For isometrics (such as L-sits), I’d suggest aiming for 10 seconds (i.e. when you hit 10 seconds you try to move on to the next variation or add weight). If you fail to do so for a long time, aim to hold it for longer (15 to 20 seconds). In terms of volume, nine weekly sets per muscle group would be a good starting point.

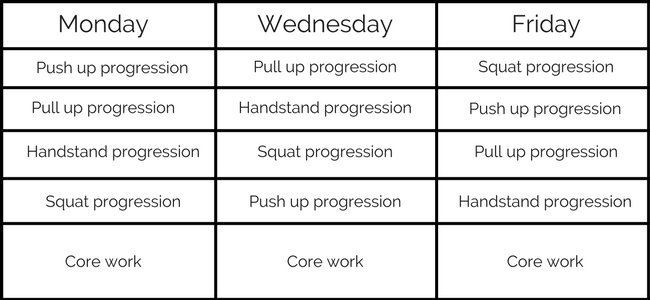

Here is an example of a full body three-day routine:

Note: This is not a one-size-fits-all routine, as with all example routines I lay out in this article. I cannot stress enough that an optimal routine requires individualization (i.e. a customized routine based on the person’s preferences).

So, this is a simple, effective full body routine for someone who’s brand new to bodyweight training. Each exercise is done for three sets of four to six reps. Once you reach six reps for every set of an exercise, you can try moving on to the harder variation next session, or you can add weight. Core work can be a combination of different exercises (see below), whichever you see fit to your goals.

Example of a beginner core workout:

- Hanging Leg Raises — 3 x 4-6

- Crunches — 3 x 10-12

- Planks — 3 x 60 seconds (once you hit 60 seconds move on to harder variations or add weight)

I’d recommend doing your core work outside of your regular sessions. Doing it at the end of your regular workouts will result in decreased work output due to you already being fatigued. Doing them at the beginning will also decrease work output in your main workout. As you become stronger at the key movements, and your work capacity rises, you should include some additional isolation exercises.

Advanced Trainees

Now, when you milk your “newbie gains” all the way through, your progression will halt. At this point, you can’t make all of your sets heavy ones (four to six reps). This would take too much time and cause too much neural fatigue. You should still include some four to six sets in your routine, but the rest should be done in eight to 10, 10 to 12, and 12 to 15 ranges — whichever higher rep range feels most comfortable to you. Additionally, you will require more volume to keep progressing. As you advance, full body workouts become inefficient, for two reasons: your workouts would become long and tedious, and your later sets would become ineffective due to the fatigue caused by the earlier sets.

If you can endure full body workouts and you enjoy doing them, by all means, continue. With most people, however, I recommend a different split (e.g. push/pull, upper/lower, etc.).

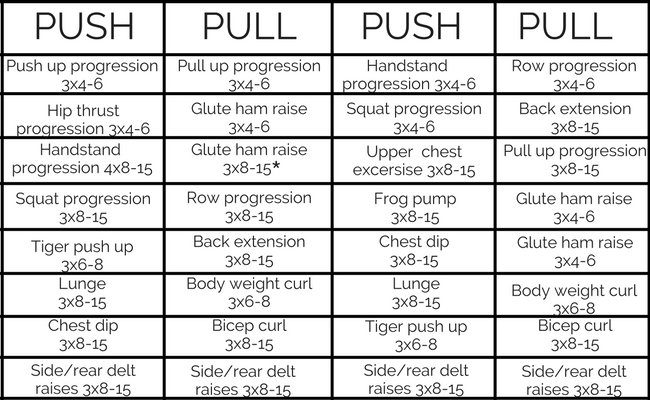

Here is an example of a non-beginner push/pull four times per week split:

Again, not a definitive routine for everyone. Just an example, okay? Core work can stay the same and be done after each workout, with more advanced variations of course. Yes, that is a shit ton of exercises to do. That is what’s needed for maximizing muscle growth. But seriously, ain’t nobody got time for that! That’s why I give you two “techniques” that you can use to save time:

Supersets

No, not the traditional type where you blast the same muscle group with two different exercises. What I’m talking about is what’s called an antagonist set in the literature. It involves pairing two different muscle groups, for the sake of saving time. For instance, on the first push day you do one set of push-ups, rest a bit (to regain your breath), and then do one set of hip thrusts. Repeat until you fulfill all your sets.

Rest-Pause Training

Rest-pause training goes like this: You do one set to near failure (you have one to two reps “left in the tank”). You rest for 10 seconds. You do another set to near failure. Repeat until you fulfill your volume. This allows you to basically complete multiple sets in a minute or two. I wouldn’t recommend this for beginners (as your form would break down) and I wouldn’t recommend it for your strength sets (four to six reps). Use this for your higher rep sets and superset your strength sets, if you want to save time.

The Importance of the Warm-Up

Let me tell you a little story. There was this guy called Richard (we’ll call him Dick for short). Dick was looking to train calisthenics, and so he went to the local street workout park. When he got there, he immediately jumped on the bar, tried to do a muscle-up, his joints cracked and he fell on the ground awkwardly, fucking up his shoulder. Point of the story: don’t be like Dick. Warm the fuck up.

A warm-up is crucial for injury prevention and better performance. To execute the movements required in calisthenics (especially as you become more advanced), you need a high degree of mobility and body awareness. A proper warm-up will allow you to work in a greater range of motion (ROM) and thus activate your muscles more. I’m not just talking about doing jumping jacks and arm circles. Those are great for raising your body temperature and warming up your joints, but a good warm-up will also include practicing an easier variation of the movement that you’re working.

MORE: Six Bodyweight Exercises That Should Be In Every Training Program

For instance, if your program calls for three sets of push-ups, and you managed to do six last time, you should warm up with knee-on-the-ground push-ups, since they’re an easier variation, then doing one set with 50% of the reps you did last time (in this example, three push-ups). If you’re doing a pull-up, you would do assisted pull-ups or half pull-ups and one set of pull-ups with 50% of the reps.

The goal of the warm-up sets shouldn’t be to tire you out, but to, you know, warm you up. On a scale of one to 10, they should be a five in terms of how hard they are.

So, in essence, here’s how a proper warm-up should be:

- 30 to 60 seconds of arm circles, leg raises, scapular pull-ups, etc.

- Set of knee push-ups

- Rest 30 seconds

- Set of knee push-ups

- Rest 30 seconds

- Do 50% reps of a push-up

- Rest 60 seconds

Then you proceed to your real sets. When doing a full body routine, it may seem tedious to constantly do the warm-up sets, but they are very important. What's more, you don’t need to do both warm-up sets for chest and shoulder exercises, as a chest exercise will warm up the shoulders and vice versa.

Flexibility Training

Good flexibility and mobility is crucial for calisthenics, especially later on as you progress to more difficult movements. This is why you need to include some stretching in your day. It doesn’t have to be complicated; just three to four stretches, held for 15 to 20 seconds. Strive to increase the range of motion each time (e.g. for a gymnastic split, try to go deeper each time). If you’re looking for a more advanced routine, Starting Stretching is a good place to start.

Ring Work

Rings are an awesome training tool, but it takes a while until you can do any type of movements on them. When you decide to move on to ring variations, you should care to include some skill work on rings. Skill work is basic stuff like ring hangs and ring holds. These movements will adjust you to the destabilized nature of the rings, so you can perform more advanced movements on them.

Header image credit: Альберт Шакиров © 123rf.com

4 Comments